The Justices of the Peace and the Administration of Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Let Single Storey Part Lofty Industrial

On the instructions of J R Burrows Ltd TO LET SINGLE STOREY PART LOFTY INDUSTRIAL/WAREHOUSE UNITS CARLINGHOW MILLS, BRADFORD ROAD, BATLEY, WEST YORKSHIRE, WF17 8LN 497 - 694m2 (5,355 -7,472 sq ft) . Highly prominent lofty warehouse unit immediately adjacent Bradford Road . Single storey engineering/industrial space . Both immediately available for early occupation *RENTS REDUCED* Location Rating Carlinghow Mills is situated in a highly prominent position with direct We are verbally advised by Kirklees Metropolitan Council the premises frontage to the A652 Bradford Road only a short distance from Batley are assessed as follows:- town centre and less than two miles to the north west of Dewsbury. The A652 Bradford Road links Dewsbury with Bradford, via Birstall, Unit V2 Carlinghow Mills £12,250 and allows access to the majority of main arterial routes serving the 507 Bradford Road, Carlinghow Mills (workshop only) £16,500 north Kirklees/Heavy Woollen district. The National Uniform Business Rate for 2014/15 is 48.6p in the £, The A652 Bradford Road junction with the main A62 Leeds Road is ignoring transitional phasing relief and allowances to small businesses. less than two miles to the north and provides direct access to junction 25 and 27 of the M62 (at Brighouse and Birstall respectively). These Prospective tenants should satisfy themselves with regard to all rating junctions of the M62, along with junction 26 at Cleckheaton, are all and planning matters direct with the Local Authority, Kirklees MC Tel: within a seven mile radius and junction 40 of the M1 is within ten miles. 01484 221000. Description Energy Performance Certificate Carlinghow Mills is a successful multi occupied mill complex providing The Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) for Unit V2 is below. -

U DDBA Papers of the Barnards Family 1401-1945 of South Cave

Hull History Centre: Papers of the Barnards Family of South Cave U DDBA Papers of the Barnards Family 1401-1945 of South Cave Historical background: The papers relate to the branch of the family headed by Leuyns Boldero Barnard who began building up a landed estate centred on South Cave in the mid-eighteenth century. His inherited ancestry can be traced back to William and Elizabeth Barnard in the late sixteenth century. Their son, William Barnard, became mayor of Hull and died in 1614. Of his seven sons, two of them also served time as mayor of Hull, including the sixth son, Henry Barnard (d.1661), through whose direct descendants Leuyns Boldero Barnard was eventually destined to succeed. Henry Barnard, married Frances Spurrier and together had a son and a daughter. His daughter, Frances, married William Thompson MP of Humbleton and his son, Edward Barnard, who lived at North Dalton, was recorder of Hull and Beverley from the early 1660s until 1686 when he died. He and his wife Margaret, who was also from the Thompson family, had at least seven children, the eldest of whom, Edward Barnard (d.1714), had five children some of whom died without issue and some had only female heirs. The second son, William Barnard (d.1718) married Mary Perrot, the daughter of a York alderman, but had no children. The third son, Henry Barnard (will at U DDBA/14/3), married Eleanor Lowther, but he also died, in 1769 at the age of 94, without issue. From the death of Henry Barnard in 1769 the family inheritance moved laterally. -

Properties for Customers of the Leeds Homes Register

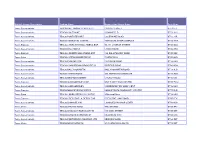

Welcome to our weekly list of available properties for customers of the Leeds Homes Register. Bidding finishes Monday at 11.59pm. For further information on the properties listed below, how to bid and how they are let please check our website www.leedshomes.org.uk or telephone 0113 222 4413. Please have your application number and CBL references to hand. Alternatively, you can call into your local One Stop Centre or Community Hub for assistance. Date of Registration (DOR) : Homes advertised as date of registration (DOR) will be let to the bidder with the earliest date of registration and a local c onnection to the Ward area. Successful bidders will need to provide proof of local connection within 3 days of it being requested. Maps of Ward areas can be found at www.leeds.gov.uk/wardmaps Aug 11 2021 to Aug 16 2021 Ref Landlord Address Area Beds Type Sheltered Adapted Rent Description DOR Silkstone House, Fox Lane, Allerton Single or a couple 11029 Home Group Bywater, WF10 2FP Kippax and Methley 1 Flat No No 411.11 No BAILEYS HILL, SEACROFT, LEEDS, Single/couple 11041 The Guinness LS14 6PS Killingbeck and Seacroft 1 Flat No No 76.58 No CLYDE COURT, ARMLEY, LEEDS, LS12 Single/couple 11073 Leeds City Council 1XN Armley 1 Bedsit No No 63.80 No MOUNT PLEASANT, KIPPAX, LEEDS, Single 55+ 11063 Leeds City Council LS25 7AR Kippax and Methley 1 Bedsit No No 83.60 No SAXON GROVE, MOORTOWN, LEEDS, Single/couple 11059 Leeds City Council LS17 5DZ Alwoodley 1 Flat No No 68.60 No FAIRFIELD CLOSE, BRAMLEY, LEEDS, Single/couple 25+ 11047 Leeds City Council -

The Boundary Committee for England Periodic Electoral Review of Leeds

K ROAD BARWIC School School Def School STANKS R I School N G R O A D PARLINGTON CP C R O PARKLANDS S S G A T E S HAREWOOD WARD KILLINGBECK AND School PENDA'S FIELDS SEACROFT WARD MANSTON CROSS GATES AND WHINMOOR WARD D A O BARWICK IN ELMET AND R Def D R O SCHOLES CP F R E Def B A CROSS GATES ROAD U n S T d A T I O Barnbow Common N R School O A D Seacroft Hospital Def A 6 5 6 2 4 6 A f De R IN G R O A D H A Def L A T U O S N T H O R P E GRAVELEYTHORPE L A N E U f nd e D N EW HO LD NE LA IRK ITK Elmfield WH nd Business U Park Newhold Industrial Estate E Recreation AN AUSTHORPE Y L Ground WB RO BAR School f e School STURTON GRANGE CP D A 6 5 WHITKIRK LANE END AUSTHORPE WEST 6 PARISH WARD AUSTHORPE CP MOOR GARFORTH School EAST GARFORTH The Oval f AUSTHORPE EAST e D PARISH WARD SE School LB Y RO AD f e D Recreation Football Ground Ground Cricket Ground f e D Swillington Common COLTON School CHURCH GARFORTH School Cricket Ground Allotment Gardens LIDGETT f e D School GARFORTH TEMPLE NEWSAM WARD Schools Swillington Common U D A n College O d R m a s a N n w A e e r M n A O le s B t p r R U m o P e p L T S L E C R T H OR D P L E L E A WEST I N E GARFORTH F E L K C I M SE LB Y R O D AD e f A 63 Hollinthorpe Hollinthorpe 6 5 D 6 e A A 63 f A LE ED S School RO A D D i s m a n t le d R a il w a y K ip p a x B e c k Def SWILLINGTON CP Kippax Common Recreation Ground Ledston Newsam GARFORTH AND SWILLINGTON WARD Luck Green Swillington School School Kippax School Allotment Gardens School D A O R E G D I R Allotment Sports Ground Gardens Sports Grounds -

Roads Turnpike Trusts Eastern Yorkshire

E.Y. LOCAL HISTORY SERIES: No. 18 ROADS TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE br K. A. MAC.\\AHO.' EAST YORKSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY 1964 Ffve Shillings Further topies of this pamphlet (pnce ss. to members, 5s. to wm members) and of others in the series may be obtained from the Secretary.East Yorkshire Local History Society, 2, St. Martin's Lane, Mitklegate, York. ROADS AND TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE by K. A. MACMAHON, Senior Staff Tutor in Local History, The University of Hull © East YQrk.;hiT~ Local History Society '96' ROADS AND TURNPIKE TRUSTS IN EASTERN YORKSHIRE A major purpose of this survey is to discuss the ongms, evolution and eventual decline of the turnpike trusts in eastern Yorkshire. The turnpike trust was essentially an ad hoc device to ensure the conservation, construction and repair of regionaIly important sections of public highway and its activities were cornple menrary and ancillary to the recognised contemporary methods of road maintenance which were based on the parish as the adminis trative unit. As a necessary introduction to this theme, therefore, this essay will review, with appropriate local and regional illustration, certain major features ofroad history from medieval times onwards, and against this background will then proceed to consider the history of the trusts in East Yorkshire and the roads they controlled. Based substantially on extant record material, notice will be taken of various aspects of administration and finance and of the problems ofthe trusts after c. 1840 when evidence oftheir decline and inevit able extinction was beginning to be apparent. .. * * * Like the Romans two thousand years ago, we ofthe twentieth century tend to regard a road primarily as a continuous strip ofwel1 prepared surface designed for the easy and speedy movement ofman and his transport vehicles. -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

S-2365-12 Visitationyorks

12 ingbah(s lli.sitation of tork.sbirt, WITH ADDITIONS. (Continued from Vol. XIX, p. 262.) AGBBIGG AND MOBLEY WAPENTAKE. He.llifu, 2° April 1666. of ltatborp-1jall. ABMS :-Ar~cnt, a cockatrice with wings addorsed and tail nowed Sable, crested G ules, I. JVILLIAJl LANGLEY, of Langley, 2 If. 6, mar, Alice ... They had i!!llue- II. TIIOJlAS LANGLEY, of Lanyl,iy, mar, . They had issue- l/enry (III). Thomas Lmiyley, L" Chancel/our of Enyland 1405-7, 1417-22, Bishop of Durham 1406, Cardinal 1411, d. 20 Nov, 1437, bur. in Durham Ca.thedra.l, M.I. (see Diet. Nat. Biog.). · III. HENRY LANGLEY of Dalton; mar .... dau, of . Ka.ye, of W oodsome (Glover). Thomas (IV). Robert Langley (see Langley, of Sheriff Hutton). IV. TIIOJEAS LANGLEl', of Rathorp Hall, in Dalton, in com. Ebor., Inq. P.M. 27 Aug. 10 Hen. VIII, 1518, sa.yH he d. 28 ·Apr. l11.11t; mar. Mar91, dauqhter of ... Wombioell, of Wombicell, They had issue- Richard (V}. Agnes, named in her brother Richard's will. V. RICIIARD LANGLEY, of Rathorp /Iall, ret. fourteen a.t his father's Inq. P.M. Will 28 Sept. 1537, pr. at York 2 Oct. 1539 (Test. Ebor., vol. vi, 70); mar. Jane, daughter of Thomas Beaumont, of Mir.field. They had issue- DUGDALE'S VISITATION OF YORKSHIRE. 13 Richard (YI). Thomas Langley, of Meltonby, named in his father's will ; mar. Agnes, da. of IVill'm Tates. They had issue- Margaret, l Alice, J Glover. Jane, Arthur, } Alice, named in their father's will. Margaret, VI. -

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number and Street Name

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number And Street Name Post Code Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMONEY CASTLE ST CASTLE STREET BT53 6JT Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COLERAINE 2 BANNFIELD BT52 1HU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTSTEWART COLERAINE ROAD BT55 7JR Tesco Supermarkets TESCO YORKGATE CENTRE YORKGATE SHOP COMPLEX BT15 1WA Tesco Express TESCO CHURCH ST BALLYMENA EXP 99-111 CHURCH STREET BT43 8DG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMENA LARNE ROAD BT42 3HB Tesco Express TESCO CARNINY BALLYMENA EXP 144 BALLYMONEY ROAD BT43 5BZ Tesco Extra TESCO ANTRIM MASSEREENE CASTLEWAY BT41 4AB Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ENNISKILLEN 11 DUBLIN ROAD BT74 6HN Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COOKSTOWN BROADFIELD ORRITOR ROAD BT80 8BH Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYGOMARTIN BALLYGOMARTIN ROAD BT13 3LD Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ANTRIM ROAD 405 ANTRIM RD STORE439 BT15 3BG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO NEWTOWNABBEY CHURCH ROAD BT36 6YJ Tesco Express TESCO GLENGORMLEY EXP UNIT 5 MAYFIELD CENTRE BT36 7WU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO GLENGORMLEY CARNMONEY RD SHOP CENT BT36 6HD Tesco Express TESCO MONKSTOWN EXPRES MONKSTOWN COMMUNITY CENTRE BT37 0LG Tesco Extra TESCO CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE 8 Minorca Place BT38 8AU Tesco Express TESCO CRESCENT LK DERRY EXP CRESCENT LINK ROAD BT47 5FX Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LISNAGELVIN LISNAGELVIN SHOP CENTR BT47 6DA Tesco Metro TESCO STRAND ROAD THE STRAND BT48 7PY Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LIMAVADY ROEVALLEY NI 119 MAIN STREET BT49 0ET Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LURGAN CARNEGIE ST MILLENIUM WAY BT66 6AS Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTADOWN MEADOW CTR MEADOW -

The Poor Law Report Reexamined Mark Blaug

Mark Blaug TheJournal Poor of Economic Law HistoryReport, vol. Reexamined 24, n° 2, June 1964 N AN earlier article, I pleaded for a reappraisal of the Old Poor I Law.1 Despite what all the books say, the evidence that we have does not suggest that the English Poor Law as it operated before its amendment in 1834 reduced the efficiency of agricultural workers, promoted population growth, lowered wages, depressed rents, destroyed yeomanry, and compounded the burden on rate- payers. Beyond this purely negative argument, I tried to show that the Old Poor Law was essentially a device for dealing with the problems of structural unemployment and substandard wages in the lagging rural sector of a rapidly growing but still under- developed economy. It constituted, so to speak, "a welfare state in miniature," combining elements of wage-escalation, family allow- ances, unemployment compensation, and public works, all of which were administered and financed on a local level. Far from having an inhibitory effect, it probably contributed to economic expansion. At any rate, from the economic point of view, things were much the same after 1834 as before. The Poor Laws Amendment Act of 1834 marked a revolution in British social administration, but it left the structure of relief policy substantially unchanged. In the earlier article, I criticized the commissioners who prepared the famous Poor Law Report of 1834 for the manner in which they marshaled the evidence against the existing system, noting that the elaborate questionnaire which they circulated among the parishes was never analyzed or reduced to summary form. -

Wage Subsidisation: Some Historical Reflections

THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF WAGE SUBSIDISATION: SOME HISTORICAL REFLECTIONS ESRC Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge Working Paper No. 201 By Frank Wilkinson Centre for Business Research, and Department of Applied Economics Austin Robinson Building Sidgwick Avenue Cambridge CB3 9DE Tel: 01223 335262 e-mail: [email protected] June 2001 This Working Paper forms part of the CBR Research Programme on Corporate Governance, Contracts and Incentives Abstract Economists explain welfare dependency of the unemployed and in-work poverty by the low labour market quality of the poor. Work can be made to pay by working family tax credits. But these might lower wages and price non- recipients out of the market, widening the eligibility for the wage supplementation and raising social welfare bills. This was precisely the effect of the Speenhamland system of wage supplementation of the early 19th Century which permanently affected labour markets, and attitudes to welfare and the poor. The possibility of working family tax credit having a similar effect cannot be ruled out. JEL Codes: J58, J78, J4, I38 Keywords: Wage supplementation, welfare to work and labour markets. 2 THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF WAGE SUBSIDISATION: SOME HISTORICAL REFLECTIONS 1. Introduction The view in government circles is that the economy has now been bought under control by prudent macroeconomic management. A major remaining problem is the high level of poverty resulting from the persistence of high unemployment and the growth in the number of the working poor. The policy response to this is to make the payment of social welfare dependent on labour market participation by a variety of means, including topping up earnings to some minimum level by means of tax credits. -

A History English Agricultural Labourer

A HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH AGRICULTURAL LABOURER W. HASBACH Translated by Ruth Kenyon With a preface by Sidney Webb The first edition published in German by Messrs . Duncker and Humblot in 1894. TABLE OF CONTENTS. First English edition was published in 1908 by P . S . King & Son PAO E PREFACE ... ... ... ... ... v.. ... vi i . INTRODUCTION ..a ... ... ... ....... xiii . CHAPTER I . THE DEVELOPMENT OF A FREE LABOURINO CLASS ... ... Introductory ... ... ... ... ... i. The Manor as an Organisation of Labour ... ... ii . The Transition to an Organisation based on Rent ... iii . The Break-down of the Manor ... ... ... iv . The Transition Period ... ... ... ... CHAPTER I1. THE DSVELOPMENT OF AN AGRICULTURAL PROLETARIAT ... i. The Village of the Eighteenth Century before the Enclosures. the Engrossing of Farms. and the Revolution in Prices ... ... ... ... ii . The Break-up of the Village ... ... ... iii . The Position of the Labourer. 1760 to 1800 ... ... iv . Contemporary Opinion ... ... ... ... CHAPTER 111. THE DENIORALISATION OF THE LABOURER ... ... ... i. The Laws of Settlement and Removal ... ... ii . The Labourer in the period of high Corn Prices ... iii . The Labourer in the period of low Corn Prices and the old Poor Law ... ... ... ... ... iv . The Gang System ... ... ... ... ... v . Wages and Moral Conditions up to 1834 ... ... CHAPTER IV . FROM THE POOR LAW AMENDMENT ACT. 1834. TO THE EDUCATION ACTS ... ... ... ... ... i . The new Poor Law and its effects ... ... ... ii . Allotments ... ... ... ... ..a iii . The Introduction of Free Trade ... ... ... iv . The Condition of the Labourer in the Sixties ... v. The Gangs Act and the Education Acts ... ... CHAPTER V . *~RICULTURAL LABOUR UNIONS AND THE SMALL HOLDINGS MOVEMENT. 1872 to 1894 ... ... ... ... ... i . Agricult~ralLabour Unions ... ... ... (a) Introductory ... ... ... ... ... (b The Period of Triumph .. -

Schools Linking and Social Cohesion: an Evaluation of the Linking Network’S Schools Linking National Programme

FINAL REPORT July 2018 Schools Linking and Social Cohesion: An Evaluation of The Linking Network’s Schools Linking National Programme Chris Shannahan Centre for Trust Peace and Social Relations Coventry University FINDINGS 1 FINAL REPORT July 2018 About the Author Acknowledgements Dr Chris Shannahan is a Research Fellow in Faith and This Report could not have been written without the Peaceful Relations at the Centre for Trust, Peace and generous support and invaluable advice of a number of Social Relations at Coventry University. Previously he was people. First, it is important to recognise the ongoing the head of Religious Education in a large Secondary support of the Pears Foundation for The Linking Network, school in London; a youth worker Trenchtown, Jamaica; without whom it would not have been possible to develop a Methodist Minister in Montserrat in the Caribbean and the Schools Linking National Programme. Second, the London and Birmingham in the UK and a community moral and financial support of the Ministry for Housing, organiser. This provided the grounding for his PhD Communities and Local Government and the Department research developing the first critical analysis of urban for Education for Schools Linking and for this evaluation theology in the UK (2008, University of Birmingham). has been invaluable. Third, it is important to thank the Prior to moving to Coventry University, he worked at local area linking facilitators who give their time to the University of Birmingham and the University of develop Schools Linking and who have engaged fully Manchester as a Lecturer in Religion and Theology. and enthusiastically with this evaluation project.