“The Obligations of Citizenship”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside • Academe Vol

Inside • Academe Vol. XV • No. 1 • 2009–2010 A publication of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni In This Issue… “What will they learn?” Project Makes a Splash By David Azerrad, Program Officer 2 In Box hree months ago, ACTA unveiled a Stories about ACTA’s new college guide 3 University Cuts new college guide website that, unlike have appeared in more than 160 different Economics Department T all the other rankings, grades universities on newspapers across the country with an esti- 4 Report Card in Illinois education and not reputation. WhatWill- mated total readership of 20 million. Most TheyLearn.com assigns each institution a notably, ACTA’s initiative was praised in 5 UDC Stays the Course grade ranging from “A” to “F” based on how two separate Wall Street Journal columns, Coming Soon: many of the following seven core subjects featured in the Daily News (New York), Increasing Account- it requires: the Houston ability in Higher Composition, Chronicle, Education Mathematics, Investor’s 6 2009 ATHENA Science, Eco- Business Roundtable nomics, For- Daily, and eign Language, picked up by 8 KC Johnson Receives Literature, the Associ- 2009 Philip Merrill and U.S. ated Press. Award Government ACTA’s focus 9 Honoring Our Heroes or History. on education at Harvard Launched and our argu- Reforming the at the National ments for a Politically Correct Press Club, rigorous and University WhatWillTheyLearn.com has since attracted coherent curriculum have been discussed on more than 40,000 visitors, in part due to a CNN, Fox Business News, and numerous 10 Best of the Blog full-page ad on the inside cover of the 2010 local television and radio stations as well as Pesile Awards Honorary U.S. -

Downloads, Distributed Freedom Professor Abigail Thompson, Chair of Nearly 30,000 Printed Copies, and Have Gone Into

Then & Now ACTA’s 25-Year Drive to Restore the Promise of Higher Education ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Stephen Joel Trachtenberg Sidney L. Gulick III Board of Directors President Emeritus and University Professor Emeritus Professor of Mathematics, University of Maryland Edwin D. Williamson, Esq., Chairman of Public Service, The George Washington University Robert “KC” Johnson Partner, Sullivan & Cromwell, LLP (ret.) Michael B. Poliakoff, Ph.D. Professor of History, CUNY–Brooklyn College Robert T. Lewit, M.D., Treasurer President, ACTA (ex-officio) Anatoly M. Khazanov CEO, Metropolitan Psychiatric Group (ret.) Ernest Gellner Professor of Anthropology Emeritus, John D. Fonte, Ph.D., Secretary & Asst. Treas. Council of Scholars University of Wisconsin; Fellow, British Academy Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute George E. Andrews Alan Charles Kors John W. Altman Evan Pugh University Professor of Mathematics, Henry Charles Lea Professor Emeritus of History, Entrepreneur Pennsylvania State University University of Pennsylvania Former Trustee, Miami University Mark Bauerlein Jon D. Levenson George “Hank” Brown Emeritus Professor of English, Emory University Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies, Harvard Divinity School Former U.S. Senator Marc Zvi Brettler Former President, University of Colorado Bernice and Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Molly Levine Janice Rogers Brown Judaic Studies, Duke University Professor of Classics, Howard University Former Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals, D.C. Cir. William Cook George R. Lucas, Jr. Former Justice of the California Supreme Court Emeritus Distinguished Teaching Professor and Emeritus Senior Fellow, Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership, Jane Fraser Professor of History, SUNY–Geneseo United States Naval Academy President, Stuttering Foundation of America Paul Davies Joyce Lee Malcolm Heidi Ganahl Professor of Philosophy, College of William & Mary Professor Emerita of Law, George Mason University Fellow of the Royal Historical Society Founder, SheFactor & Camp Bow Wow David C. -

Reflections on the New Era: Reassessing the 1920S

Reflections on The New Era: Reassessing the 1920s November 14-15, 2014 Williams College This conference is sponsored by the Stanley Kaplan Program in American Foreign Policy and the Program in Leadership Studies at Williams College. Conference Schedule Friday, November 14 Keynote Address – Rethinking the Crisis of Democratic Theory: The Political Thought of Walter Lippmann, John Dewey, and H.L. Mencken in the 1920s David Greenberg, Rutgers University Saturday, November 15 All events take place in Griffin Hall, Room 3 8:30 AM Continental Breakfast 9:00 AM Roundtable #1 - Legacies of Wilsonianism and Progressivism in the 1920s Comments: George H. Nash, The Russell Kirk Center Panelists: Christopher McKnight Nichols, Oregon State University Justus Doenecke, New College of Florida John Fox, The Federal Bureau of Investigation 10:30 AM Coffee Break 10:45 AM Roundtable #2 - Foreign Relations and Political History Comments: Marc Gallicchio, Villanova University Panelists: Robert David (KC) Johnson, Brooklyn College Richard G. Frederick, University of Pittsburgh at Bradford James McAllister, Williams College 12:30 PM Buffet Lunch, Griffin Hall, Room 4 1:45 PM Roundtable #3 - Social, Economic, and Cultural History Comments: Alex Pavuk, Morgan State University Panelists: Ruth Clifford Engs, Indiana University Carol Jackson Adams, Webster University Derek Hoff, Kansas State University 3:15 PM Coffee Break 3:30 PM Rountable #4 - First Ladies Comments: Maurine Beasley, University of Maryland Panelists: Katherine A.S. Sibley, Saint Joseph’s University Teri Finneman, Missouri School of Journalism Nancy Beck Young, University of Houston 6:30 PM Dinner: Sushi Thai Garden, Spring Street.Williamstown, MA Optional Keynote Speaker DAVID GREENBERG is an associate professor of History and of Journalism & Media Studies at Rutgers University and a frequent commentator in the national news media on politics and public affairs. -

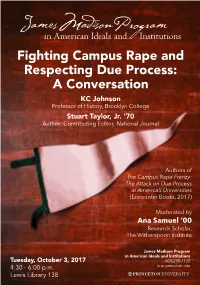

Fighting Campus Rape and Respecting Due Process: a Conversation KC Johnson Professor of History, Brooklyn College Stuart Taylor, Jr

Fighting Campus Rape and Respecting Due Process: A Conversation KC Johnson Professor of History, Brooklyn College Stuart Taylor, Jr. ‘70 Author; Contributing Editor, National Journal Authors of The Campus Rape Frenzy: The Attack on Due Process at America’s Universities (Encounter Books, 2017) Moderated by Ana Samuel ‘00 Research Scholar, The Witherspoon Institute James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions Tuesday, October 3, 2017 609-258-1122 4:30 - 6:00 p.m. jmp.princeton.edu Lewis Library 138 KC JOHNSON is Professor of History at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, where he specializes in U.S. political, diplomatic, and constitutional history. He has taught at Arizona State University and Williams College and has served as a visiting professor at Harvard University and at Tel Aviv University, where he was Fulbright Distinguished Chair in the Humanities. He has written or edited thirteen books, on topics ranging from congressional history to the Lyndon Johnson tapes to the historical and contemporary application of Title IX. His latest book, coauthored with Stuart Taylor, Jr., is The Campus Rape Frenzy: The Attack on Due Process at America’s Universities (Encounter Books, 2017). He received his BA and PhD from Harvard University and his MA from the University of Chicago. STUART TAYLOR, JR. ‘70 is an author and freelance journalist focusing on legal and policy issues. He has coauthored three critically acclaimed books, and has written for leading publications since 1980, including The New York Times, American Lawyer Media, National Journal, Newsweek, and many other newspapers and magazines. He has been interviewed on all major broadcast networks and has won numerous journalism honors. -

Science Connected

he experiment is to be tried… SUMMER 2017 whether the children of the people, ‘Tthe children of the whole people, can be educated; whether an institution of learning, of the highest grade, can be successfully controlled by the popular will, not by the privileged few, but by the privileged many.” — Horace Webster Founding Principal, The Free Academy CUNYcuny.edu/news • THE CITY UNIVERSITYMatters OF NEW YORK • FOUNDED 1847 GRANTS&HONORS Recognizing Faculty Achievement he University’s Mogulescu renowned faculty Tmembers continually win professional achievement awards from prestigious organizations as well as research grants from government agencies, Spokony farsighted foundations and leading corporations. Pictured are just a few of the recent honorees. Brief summaries of many ongoing research projects start here and continue inside. Ahmed John Mogulescu, Senior University Dean for Academic Affairs and Dean of the School of Professional Studies, has been awarded a four-year grant totaling Knikou nearly $6 million from the U.S. Department of Labor for CUNY TechWorks, a partner- ship with Borough of Man- hattan, Kingsborough and Queensborough Community Spear Colleges to strengthen career-focused associate degree programs in software application development, web development, and IT systems administration. The At the Graduate Center’s ASRC program will serve 1,225 students over the grant Rauceo period. Valerie Westphal headed the proposal effort, while Nikki Evans created Science Connected the concept and wrote the winning application with HEN -

The US and North Africa KC Johnson

Brooklyn College The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the Department of Classics, the Department of Judaic Studies, the Department of History, and the School of Education, presents An Interdisciplinary Colloquium North Africa and the Wider World The Revolt of the Libyans, 240BCE Liv Mariah Yarrow, associate professor of classics, Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Spain, Morocco, and Islam before 1800 Justin Stearns, assistant professor in the Arab Crossroads Studies program, NYU - Abu Dhabi. Historical Thought on France and the Maghreb since 1830 David G. Troyansky, professor of history, Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. The Western Allies Invade North Africa...in 1942 Sara Reguer, professor of Judaic studies, Brooklyn College. Sporadic Interest: The U.S. and North Africa KC Johnson, professor of history, Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Naming and Deterritorializing Events in North Africa Marnia Lazreg, professor of sociology, Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Thursday, April 28, 2011 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. 3129 Boylan Hall Brooklyn College For Information: (718) 951-5847 [email protected] Speaker Biographies The Revolt of the Libyans, 240BCE Liv Mariah Yarrow is associate professor of classics at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, where she specializes in Roman and Hellenistic History. She is the author of Historiography at the End of the Republic (Oxford University Press) and co-editor of Polybius, Imperialism, and Cultural Politics (Oxford University Press). She is currently working on a history of Rome down to 49BCE as seen through the numismatic evidence for a series jointly published by Cambridge University Press and the American Numismatic Society. -

Inside • Academe Vol

Inside • Academe Vol. XIV • No. 4 • 2008–2009 A publication of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni In This Issue… Prominent Colleges Take Steps on Intellectual Diversity 2 In Box hat do the University System of To pick just a few examples: In Georgia You’re Invited to WGeorgia, the University of Missouri and Missouri, ACTA’s State Higher Educa- System, the University of North Carolina at tion Report Cards helped produce reforms. ATHENA Chapel Hill, Old Dominion University, the Steps forward at Old Dominion and the University of Pennsylva- South Dakota system 3 KC Johnson to Receive nia, the City University came in response to the th 5 Annual Philip of New York, Amherst introduction of sunlight Protecting the Free Exchange of Ideas Merrill Award College, and Dartmouth legislation based on our How Trustees Can Advance Intellectual Diversity on Campus College all have in com- previous report, Intellec- 4 Breaking News mon? They are just a tual Diversity: Time for New College Guide few of the well-known Action. A unique lecture colleges and universities Asks: What Will They series at Harvard Law that have taken concrete came at the behest of a Learn? action—in line with member of ACTA’s Do- ACTA’s recommenda- Donors Establish New nors Working Group. tions—to protect intellec- And as readers of Inside Fellowships tual diversity on campus. Academe know, reform- That’s what our newest minded trustees and 5 Heard on Campus trustee guide, Protecting alumni at CUNY and Course Syllabi Are American Council of Trustees and Alumni the Free Exchange of Ideas, Institute for Effective Governance Dartmouth have worked Coming to a Computer shows. -

Presidents and Executive Politics – Faculty Homepages and Presidency Course Syllabi

Presidents and Executive Politics – Faculty Homepages and Presidency Course Syllabi This is a faculty homepage and presidency course syllabus list for convenient reference by PEP members and any other interested persons. The list is organized alphabetically by each member’s last name, followed by each member’s institutional affiliation, homepage link (if available), and presidency syllabus link (if available). If you would like to be added to (or removed from) the list, or if you would like any corrections or updates, please send an e-mail request to José D. Villalobos at: [email protected]. Philip R. Abbott Wayne State University Homepage: http://www.clas.wayne.edu/faculty/abbott Syllabus link: Joel Aberbach University of California, Los Angeles Homepage: http://www.spa.ucla.edu/dept.cfm?d=ps&s=faculty&f=faculty1.cfm&id=1; http://www.polisci.ucla.edu/people/faculty-pages/joel-d-aberbach Syllabus link: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/classes/profbylid.php?lid=582&order=term&dept=P OL+SCI Randall Adkins University of Nebraska at Omaha Homepage: http://www.unomaha.edu/psci/adkins.php Syllabus link: Gary G. Aguiar South Dakota State University Homepage: http://garyaguiar.com/ Syllabus link: David W. Ahern University of Dayton Homepage: http://homepages.udayton.edu/~aherndaw/ Syllabus link: http://homepages.udayton.edu/~aherndaw/index313.htm Sunil Ahuja Youngstown State University Homepage: http://www.as.ysu.edu/~polisci/ahuja.html Syllabus Link: http://www.as.ysu.edu/~polisci/Presidency_SyllabusAhuja.pdf Richard Allen Stanford University Homepage: http://www.hoover.org/fellows/10187 Syllabus Link: Victoria Allen CUNY-Queens College Homepage: http://qcpages.qc.cuny.edu/political_science/allen.html Syllabus Link: http://courses.qc.cuny.edu/?list=Courses&department=PSCI&course=212&profe ssor=ALLEN,%20VICTORIA&display=survey&first_letter_selector=A Craig W. -

Temperate Radicals

WHAT will they LEARN will they WHAT A Survey of Core Requirements at Our Nation’s Colleges and Universities ? 2013-14 Getting What You Pay For? 20A Look at America’s Top-Ranked Public Universities April 2014 AMERICAN COUNCIL OF TRUSTEES AND ALUMNI “A survey of recentTEMPERATE college graduates commissioned RADICALS by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni ... found that barelyCelebrating half knew that the U.S. two Constitution decades of hard-charging higher education reform establishes the separation of powers .... 62% didn’t know the correct length of congressional terms of office.” 2015 Board of Directors Council of Scholars Robert T. Lewit, M.D., Chairman George E. Andrews Anatoly M. Khazanov Former CEO, Metropolitan Psychiatric Group Evan Pugh Professor of Mathematics Ernest Gellner Professor of Anthropology Emeritus, Pennsylvania State University University of Wisconsin; Fellow of the British Academy John D. Fonte, Ph.D., Secretary Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Mark Bauerlein Alan Charles Kors Visiting Scholar, American Enterprise Institute Professor of English, Emory University Henry Charles Lea Professor of History University of Pennsylvania Jane Fraser Marc Zvi Brettler President, Stuttering Foundation of America Bernice and Morton Lerner Professor of Judaic Studies Jon D. Levenson Duke University Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies Edwin Meese III, Esq. Harvard Divinity School Former Attorney General of the United States William Cook Molly Levine Former Rector, George Mason University Distinguished Teaching Professor and Emeritus Professor of History, SUNY–Geneseo Professor and Chair of Classics, Howard University Carl B. Menges Paul Davies George R. Lucas, Jr. Former Vice Chairman, Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette Professor of Philosophy, College of William & Mary Distinguished Chair in Ethics Emeritus, U.S. -

Colleges Call in Legal Pros to Handle Sexual-Assault Cases

Colleges Call in Legal Pros to Handle Sexual-Assault Cases Kelvin Ma for The Chronicle Djuna Perkins, a trial lawyer, opened a law firm in Massachusetts in 2012 to guide colleges through sexual-assault cases. She has worked on 35 such investigations with about a dozen colleges, she says. By Robin Wilson It’s a story like those many colleges are hearing. A young man and woman were hanging out in her room, talking, doing shots. She drank so much, she says, that she passed out—and woke up to discover she was bleeding. The man, she says, had sexually assaulted her. But he says she’d had just a few drinks and consented to sex. How does the college determine who is more credible? In this case, administrators hired Allyson Kurker, a lawyer who investigates reports of campus sexual assault by conducting extensive interviews and reviewing cellphone and swipe-card records, photos, and videos. Interviews with students led her to two other women who described similar but as yet unreported experiences with the same man. The college found him responsible in all three cases and expelled him. Legally obligated to respond to reports of sexual assault, colleges often find that students rely on them rather than law-enforcement agencies, which are seen as intimidating and unlikely to pursue charges. To meet the demand, colleges are turning to experts, setting up a kind of shadow justice system. It is now possible for an institution that receives a report of an assault to hire a former prosecutor to investigate the case and a former judge to help decide it. -

Campus Courts in Court: the Rise in Judicial Involvement in Campus Sexual Misconduct Adjudications

41822-nyl_22-1 Sheet No. 28 Side A 12/03/2019 11:18:04 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYL\22-1\NYL102.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-DEC-19 9:05 CAMPUS COURTS IN COURT: THE RISE IN JUDICIAL INVOLVEMENT IN CAMPUS SEXUAL MISCONDUCT ADJUDICATIONS Samantha Harris* & KC Johnson** This Article analyzes the recent wave of litigation involving students accused of sexual misconduct and tried in campus judiciaries. Historically, federal courts have concluded that universities themselves, rather than judges, are best suited to determine appropriate disciplinary procedures for adjudicating student conduct violations, but that has begun to change. The U.S. Department of Education’s 2011 reinterpretation of Title IX, combined with the efforts of activist students, faculty, and administrators, pressured universities to adopt procedures that all but ensured schools would find more accused students responsible in campus sexual misconduct cases. Ten- tatively at first, and more aggressively in the past several years, courts have ruled against universities in lawsuits filed by accused students. Judges have expressed concerns about colleges failing to respect the due process or pro- cedural fairness rights of their students, discriminating against accused stu- dents in violation of Title IX, and failing to adhere to their own contractual obligations. Since the 2011 policy change, more than 500 accused students have filed lawsuits against their college or university, a wave of litigation that has continued even after the Department of Education rescinded the 2011 guidance in 2017. More than 340 of those lawsuits have been brought in federal court; colleges have been on the losing end of more than 90 federal decisions, with more than 70 additional lawsuits settled by the school prior to any decision. -

Tenure, Job Security, Academic Freedom, Freedom of Speech 09.09.Doc

1 Tenure, Job security, Academic Freedom, Freedom of Speech 09.09.doc “Students need professors with job security , continuity and academic freedom to address challenging topics and maintain high standards.” - “Joint Statement Urging the KCTCS To Restore Tenure and Regain the Academic Community’s Confidence.” April 24, 2009. http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/newsroom/2009PRS/AAUPAFTKCTCS.htm “The tenure system has been under particularly heavy fire since the mid-1990s, when some higher education gurus, exasperated by the stubbornness of tenured faculty in refusing to pay attention to undergraduate teaching reforms, began to ally themselves with managerial gurus who advocated the abolition of the job security of tenure in order to ensure “nimble” responses to changing circumstances. They also believed that ambition would lapse in the modern workforce if employees were not goaded by fear of firing.” - Mary Burgan, “Save Tenure Now”. Academe Sept-Oct 2008. http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/pubsres/academe/2008/SO/Feat/burg.htm “Job security , benefits, and opportunity to advance are the three working conditions that most divide non-tenure-track faculty from their tenure-track colleagues. Fully half of the full-time non-tenure-track faculty expressed dissatisfaction with their job security , compared to 34 percent of tenure-track and 3.5 percent of tenured faculty.” - “The Status of Non-Tenure-Track Faculty.” AAUP, June 1993. http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/comm/rep/nontenuretrack.htm “The growth of the contingent labor market would also be spurred if one or more of the unions that currently bargain on behalf of faculty were to take an interest in developing alternative employment contracts.