The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

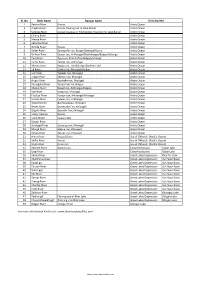

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Scout and Guide Stamps Club BULLETIN #335

Scout and Guide Stamps Club BULLETIN Volume 58 No. 3 (Whole No. 335) See article starting on page 13. MAY / JUNE 2014 1 Editorial Sorry this issue is a bit late but I gave Colin Walker extended time as he is finishing his new book on Scouting in the First World War. Since my last Editorial I have completed my last Gang Show - which went very smoothly from my point of view but I’m afraid there were a lot of complaints to the DC about my going and also the prohibiting of over 25's from appearing on stage, which he has also enforced. They are trying to put together a new team so it will be interesting to see how matters progress. I have missed out the humorous postcards from this issue as I have two interesting, but longer articles, to include. I hope that you like them. As I am typing this I have just finished watching the 70th Anniversary of D-Day events on television and the more that I watch the more that I come to admire the bravery of ordinary people - on both sides of the divide. My own father was a gunner on merchant ships during the later stages of the war (having been on a reserved occupation in the Police for the first few years). His vessel was due to be part of the first wave of the invasion and they duly left the UK loaded up with troops early on the morning of 6th June, 1944. However they only got about half way across the English Channel when the boiler on the ship failed and they then had to limp back to Portsmouth for repairs - and in the process no doubt saving a lot of lives. -

The Influence of Climatic Change and Human Activity on Erosion Processes in Sub-Arid Watersheds in Southern East Siberia

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 17, 3181–3193 (2003) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hyp.1382 The influence of climatic change and human activity on erosion processes in sub-arid watersheds in southern East Siberia Leonid M. Korytny,* Olga I. Bazhenova, Galina N. Martianova and Elena A. Ilyicheva Institute of Geography, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1 Ulanbatorskaya St., Irkutsk, 664033, Russia Abstract: A LUCIFS model variant is presented that represents the influence of climate and land use change on fluvial systems. The study considers trends of climatic characteristics (air temperature, annual precipitation totals, rainfall erosion index, aridity and continentality coefficients) for the steppe and partially wooded steppe watersheds of the south of East Siberia (the Yenisey River macro-watershed). It also describes the influence of these characteristics on erosion processes, one indicator of which is the suspended sediment yield. Changes in the river network structure (the order of rivers, lengths, etc.) as a result of agricultural activity during the 20th century are investigated by means of analysis of maps of different dates for one of the watersheds, that of the Selenga River, the biggest tributary of Lake Baikal. The study reveals an increase of erosion process intensity in the first two-thirds of the century in the Selenga River watershed and a reduction of this intensity in the last third of the century, both in the Selenga River watershed and in most of the other watersheds of the study area. Copyright 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. KEY WORDS LUCIFS; Yenisey watershed; fluvial system; climate change; land use change; river network structure; erosion processes. -

Russia Country Report: Multicultural Experience in Education

RUSSIA COUNTRY REPORT: MULTICULTURAL EXPERIENCE IN EDUCATION Leila Salekhova, Ksenia Grigorieva Kazan Federal University (RUSSIAN FEDERATION) Abstract The Russian Federation (RF) is a large country with the total area of 17,075,400 sq km. The RF has the world’s ninth-largest population of 146,600,000 people. According to the 2010 census, ethnic Russian people constitute up to 81% of the total population. In total, over 185 different ethnic groups live within the RF borders. Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism are Russia’s traditional religions. Russia is a multinational and multicultural state. The large number of different ethnic groups represents the result of a complicated history of migrations, wars and revolutions. The ethnic diversity of Russia has significantly influenced the nature of its development and has had a strong influence on the state education policy. The article gives a detailed analysis of the key factors determining educational opportunities for different RF ethnic groups. A complicated ethnic composition of Russia’s population and its multi-confessional nature cause the educational system to fulfill educational, ethno-cultural and consolidating functions by enriching the educational content with ethnic peculiarities and at the same time providing students with an opportunity to study both in native (non-Russian) and non-native (Russian) languages. The paper provides clear and thorough description of Russian educational system emphasizing positive features like high literacy and educational rates especially in technical areas that are due to the results of the educational system functioning nowadays. Teacher education is provided in different types of educational institutions allowing their graduates to start working as teachers immediately after graduating. -

Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: a Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 15 | Issue 3 Article 5 9-1-1996 Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: A Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Shamanic wisdom, parapsychological research and a transpersonal view: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15(3), 30–55.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15 (3). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies/vol15/iss3/5 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAMANIC WISDOM, PARAPSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH AND A TRANSPERSONAL VIEW: A CROSS-CULTURAL ' PERSPECTIVE LARISSA VILENSKAYA PSI RESEARCH MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA, USA There in the unbiased ether our essences balance against star weights hurled at the just now trembling scales. The ecstasy of life lives at this edge the body's memory of its immutable homeland. -Osip Mandelstam (1967, p. 124) PART I. THE LIGHT OF KNOWLEDGE: IN PURSUIT OF SLAVIC WISDOM TEACHINGS Upon the shores of afar sea A mighty green oak grows, And day and night a learned cat Walks round it on a golden chain. -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National -

Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi'nin Coğrafyasi

International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE) To Cite This Article: Can, R. R. (2021). Geography of the Trans-Baykal (Russia) region. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE), 43, 365-385. Submitted: October 07, 2020 Revised: November 01, 2020 Accepted: November 16, 2020 GEOGRAPHY OF THE TRANS-BAYKAL (RUSSIA) REGION Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi’nin Coğrafyası Reyhan Rafet CAN1 Öz Zabaykalskiy Kray (Bölge) olarak isimlendirilen saha adını Rus kâşiflerin ilk kez 1640’ta karşılaştıkları Daur halkından alır. Rusçada Zabaykalye, Balkal Gölü’nün doğusu anlamına gelir. Trans-Baykal Bölgesi, Sibirya'nın en güneydoğusunda, doğu Trans-Baykal'ın neredeyse tüm bölgesini işgal eder. Bölge şiddetli iklim koşulları; birçok mineral ve hammadde kaynağı; ormanların ve tarım arazilerinin varlığı ile karakterize edilir. Rusya Federasyonu'nun Uzakdoğu Federal Bölgesi’nin bir parçası olan on bir kurucu kuruluşu arasında bölge, alan açısından altıncı, nüfus açısından dördüncü, bölgesel ürün üretimi açısından (GRP) altıncı sıradadır. Bölge topraklarından geçen Trans-Sibirya Demiryolu yalnızca Uzak Doğu ile Rusya'nın batı bölgeleri arasında bir ulaşım bağlantısı değil, aynı zamanda Avrasya geçişini sağlayan küresel altyapının da bir parçasıdır. Bölgenin üretim yapısında sanayi, tarım ve ulaşım yüksek bir paya sahiptir. Bu çalışmada Trans-Baykal Bölgesi’nin fiziki, beşeri ve ekonomik coğrafya özellikleri ele alınmıştır. Trans-Baykal Bölgesinin coğrafi özelliklerinin yanı sıra, ekonomik ve kültürel yapısını incelenmiştir. Bu kapsamda konu ile ilgili kurumsal raporlardan ve alan araştırmalarından yararlanılmıştır. Bu çalışma sonucunda 350 yıldan beri Rus gelenek, kültür ve yaşam tarzının devam ettiği, farklı etnik grupların toplumsal birliği sağladığı, yer altı kaynaklarının bölge ekonomisi için yüzyıllardır olduğu gibi günümüzde de önem arz ettiği, coğrafyasının halkın yaşam şeklini belirdiği sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Jeweled Broom and the Dust of the World: Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Emi Joanne Foulk 2016 © Copyright by Emi Joanne Foulk 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Jeweled Broom and the Dust of the World: Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan by Emi Joanne Foulk Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Herman Ooms, Chair This dissertation seeks to reconsider the eighteenth-century kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga’s (1730-1801) conceptions of language, and in doing so also reformulate the manner in which we understand early modern kokugaku and its role in Japanese history. Previous studies have interpreted kokugaku as a linguistically constituted communitarian movement that paved the way for the makings of Japanese national identity. My analysis demonstrates, however, that Norinaga¾by far the most well-known kokugaku thinker¾was more interested in pulling a fundamental ontology out from language than tying a politics of identity into it: grammatical codes, prosodic rhythms, and sounds and their attendant sensations were taken not as tools for interpersonal communication but as themselves visible and/or audible threads in the fabric of the cosmos. Norinaga’s work was thus undergirded by a positive understanding ii of language as ontologically grounded within the cosmos, a framework he borrowed implicitly from the seventeenth-century Shingon monk Keichū (1640-1701) and esoteric Buddhist (mikkyō) theories of language. Through philological investigation into ancient texts, both Norinaga and Keichū believed, the profane dust that clouded (sacred, cosmic) truth could be swept away, as if by a jeweled broom. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Russians, Tatars and Jews by Mark Tolts

Ethnicity, Religion and Demographic Change in Russia: Russians, Tatars and Jews by Mark Tolts [Published in: Evolution or Revolution in European Population (European Population Conference, Milano 1995), Vol. 2. Milan: EAPS and IUSSP, 1996, pp. 165-179] 1. Introduction The Russian Federation is a multiethnic country. However, during many years Russia proper was only part of an even more variegated state — first the Tsarist Empire, and then the Soviet Union, which was dissolved in 1991. Therefore demographic transition was in the past studied mostly in the framework of the USSR and ethnic factors were discussed for this larger unit as a whole. This article is the first to compare ethnicity, religion and demographic change among Russians, Tatars and Jews in Russia alone. These three groups were chosen specifically because they represent distinctive religions, as well as greatly differing ethnic backgrounds and cultures. The Russians are a Slavic people whose traditional religion is Russian Orthodox Christianity. They were for many years the dominant ethnic group of the Tsarist Empire and the Soviet Union, and now form The research for this paper was funded in part by the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture. Background research is being supported by the Israel Interministry Fund ‘Tokhnit Giladi’. The author wishes to express his appreciation to Sergio DellaPergola for his advice and Evgeny Andreev and Leonid Darsky for their helpful suggestions. Mark Kupovetsky, Pavel Polian and Sergei Zakharov offered some statistical data and copies of important materials. The author is grateful to Judith Even, Eli Lederhendler and Shaul Stampfer for reading and editing an earlier draft, and to Philippa Bacal for careful typing. -

University of Groningen Genealogies Of

University of Groningen Genealogies of shamanism Boekhoven, J.W. IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2011 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Boekhoven, J. W. (2011). Genealogies of shamanism: Struggles for power, charisma and authority. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 Genealogies of Shamanism Struggles for Power, Charisma and Authority Cover photograph: Petra Giesbergen (Altaiskaya Byelka), courtesy of Petra Giesbergen (Altaiskaya Byelka) Cover design: Coltsfootmedia, Nynke Tiekstra, Noordwolde Book design: Barkhuis ISBN 9789077922880 © Copyright 2011 Jeroen Wim Boekhoven All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained here- in may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the author. -

Shamanism and the State: a Conflict Theory Perspective

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 Shamanism and the state: A conflict theory perspective David K. Gross The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gross, David K., "Shamanism and the state: A conflict theory perspective" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5552. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5552 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Hie University ofMONTANA Permission is granted by the aurhor to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for schoiariv purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature * * Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Pate & —/ T 7 - n o Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. SHAMANISM AND THE STATE: A CONFLICT THEORY PERSPECTIVE By David K. Gross M.A. The University of Montana, 2000 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2000 Approved by: Committee Chair Dean of Graduate Sctiodl UMI Number: EP41016 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.