“Coming and Going” | STEPHEN BEST Small Axe: a Caribbean Journal of Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

Medieval Glues Upto 1600 CE Class Notes - SCA Estrella 23 Collegium, Feb 18, 2007 C

Medieval Glues Upto 1600 CE Class Notes - SCA Estrella 23 Collegium, Feb 18, 2007 C. M. Helm-Clark, Ph.D. Overview of Medieval Glues There are many glues which were used in period. Several glues and glue ingredients are as follows: Cheese glue wood natural must be made up and polymer made used immediately, sets up of globular permanently, subject to polypeptide attack by casein protein microorganisms in molecules damp conditions, stronger in thin coats, impervious when cured Hide Glue general all-around glue, natural rehydration undoes the sizing, vellum, paper, polymer made adhesive, stores forever wood, gilding mordant up of strands in the dried state, can ingredient of polypeptide make stronger bonds colloid protein than cheese glue but is molecules not impervious or permanent, brittle Wheatpaste vellum, paper, Natural Weak glue, edible, bookbinding polymer made subject to attack by up of gluten microorganisms or proteins water Gum Arabic Vellum, paper, pigment A true weak glue, edible binder, food binder, vegetable gum medicine binder Gum Vellum, paper, universal An oleoresin Weak glue, can be Ammoniac gilding mordant rehydrated to a tacky state, dries hard, is flexible Turpentine Vellum, paper, pigment An oleoresin Moderate glue, dries (real period binder, gilding mordant, hard, flexible when turpentine, not wood, wood filler young, may yellow or the modern cloud with age spirit turpentine) Plasters Stone, brick, tile, Calcined Moderate to strong ceramics, masonry filler, gypsum adhesive qualities, sets mordant ingredient compounds permanently Sugar, honey mordant ingredient, food hygroscopic Weak glue, can be and medicine binder sugars rehydrated to a tacky state, subject to mold Medieval Glues class notes, copyright 2007 by Catherine Helm-Clark. -

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone

Also by Olivia Laing To the River The Trip to Echo Spring OLIVIA LAING The Lonely City Adventures in the Art of Being Alone Published in Great Britain in 2016 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE www.canongate.tv This digital edition first published in 2016 by Canongate Books Copyright © Olivia Laing, 2016 The moral right of the author has been asserted For permissions acknowledgements, please see the Notes beginning on page 285 Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN 978 1 78211 123 8 eISBN 978 1 78211 124 5 Typeset in Bembo by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire If you’re lonely, this one’s for you and every one members one of another Romans 12:5 CONTENTS 1 The Lonely City 2 Walls of Glass 3 My Heart Opens to Your Voice 4 In Loving Him 5 The Realms of the Unreal 6 At the Beginning of the End of the World 7 Render Ghosts 8 Strange Fruit Notes Bibliography Acknowledgements List of Illustrations 1 THE LONELY CITY IMAGINE STANDING BY A WINDOW at night, on the sixth or seventeenth or forty-third floor of a building. The city reveals itself as a set of cells, a hundred thousand windows, some darkened and some flooded with green or white or golden light. -

Handbook of Polysaccharides

Handbook of Polysaccharides Toolbox for Polymeric sugars Polysaccharide Review I 2 Global Reach witzerland - taad lovakia - Bratislava Synthetic laboratories Synthetic laboratories Large-scale manufacture Large-scale manufacture Distribution hub Distribution hub apan - Tokyo Sales office United Kingdom - Compton India - Chennai Synthetic laboratories Sales office United tates - an iego Distribution hub Distribution hub China - Beijing, inan, uzhou outh Korea - eoul Synthetic laboratories Sales office Large-scale manufacture Distribution hub Table of contents Section Page Section Page 1.0 Introduction 1 6.2 Examples of Secondary & Tertiary Polysaccharide Structures 26 About Biosynth Carbosynth 2 6.2.1 Cellulose 26 Product Portfolio 3 6.2.2 Carrageenan 27 Introduction 4 6.2.3 Alginate 27 2.0 Classification 5 6.2.4 Xanthan Gum 28 3.0 Properties and Applications 7 6.2.5 Pectin 28 4.0 Polysaccharide Isolation and Purification 11 6.2.6 Konjac Glucomannan 28 4.1 Isolation Techniques 12 7.0 Binary & Ternary Interactions Between Polysaccharides 29 4.2 Purification Techniques 12 7.1 Binary Interactions 30 5.0 Polysaccharide Structure Determination 13 7.2 Ternary Interactions 30 5.1 Covalent Primary Structure 13 8.0 Polysaccharide Review 31 5.1.1 Basic Structural Components 13 Introduction 32 5.1.2 Monomeric Structural Units and Substituents 13 8.1 Polysaccharides from Higher Plants 32 5.2 Linkage Positions, Branching & Anomeric Configuration 15 8.1.1 Energy Storage Polysaccharides 32 5.2.1 Methylation Analysis 16 8.1.2 Structural Polysaccharides 33 5.2.2 -

T. A. Z. the Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many-- sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok);Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic(Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

Street Art Is Visual Art Created in Public Locations, Usually Unsanctioned Artwork Executed Outside of the Context of Traditional Art Venues

Worksheet on Street Art Christine Röll What is street art? Street art is visual art created in public locations, usually unsanctioned artwork executed outside of the context of traditional art venues. Other terms for this type of art can be "urban art", "guerrilla art", "independent public art", "post-graffiti", and "neo-graffiti". Common forms and media can include spray paint graffiti, stencil graffiti (a form of graffiti that makes use of stencils made out of paper, cardboard, or other media to create an image or text that is easily reproducible), wheatpasted poster art (wheatpaste is a combination of flour, sugar, and water to put up a poster), sticker art, street installations, and sculpture. Street art is a form of artwork that is displayed in a community on its surrounding buildings, streets, and other publicly viewed surfaces. Many instances come in the form of guerrilla art, whose aim is to make a public statement about the society that the artist lives within. The work has moved from the beginnings of graffiti and vandalism to new modes where artists work to bring messages, or just simple beauty, to an audience. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Street_art Who is Banksy? Banksy is an anonymous England-based graffiti artist. His (or maybe her) satirical street art and subversive epigrams (short and interesting statements) combine dark humour with graffiti executed in a distinctive stenciling technique. Banksy's works of political and social commentary have been featured on streets, walls, and bridges of cities throughout the world. Banksy's work grew out of the Bristol underground scene, which involved collaborations between artists and musicians. -

Oral History Interview with Avram Finkelstein, 2016 April 25-May 23

Oral history interview with Avram Finkelstein, 2016 April 25-May 23 Funded by the Keith Haring Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Avram Finkelstein on April 25-May 23, 2016. The interview took place in New York, and was conducted by Cynthia Carr for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Visual Arts and the AIDS Epidemic: An Oral History Project. Avram Finkelstein has reviewed the transcript. His corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview CYNTHIA CARR: There. So okay. This is Cynthia Carr interviewing Avram Finkelstein at his studio/home in Brooklyn, New York, on April 25, 2016 for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, and this is card number one. So Avram, again, say your name and spell it. AVRAM FINKELSTEIN: Sure, it's Avram Finkelstein. A, as in apple, V, as in victor, R, as in Robert, A, as in apple, M, as in mother. F, as in Frank, I-N-K-E-L-S-T-E-I-N. CYNTHIA CARR: Okay. And when and where were you born? AVRAM FINKELSTEIN: I was born in 1952. My mother thinks I was born in Brooklyn, my sister thinks I was born in Queens. -

Oral History Interview with Joy Episalla, 2016 February 23 and March 17

Oral history interview with Joy Episalla, 2016 February 23 and March 17 Funded by the Keith Haring Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Joy Episalla on 2016 February 23- March 17. The interview took place in New York, N.Y., and was conducted by Cynthia Carr for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Archives of American Art's Visual Arts and the AIDS Epidemic: An Oral History Project. Joy Episalla and Cynthia Carr have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview CYNTHIA CARR: Okay. This is Cynthia Carr interviewing Joy Episalla, at Joy's home in New York, New York, in the East Village on February 23, 2016, for the Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution, Card Number One. So Joy, could you say your name and spell Episalla? JOY EPISALLA: Sure. Joy Episalla. And it's E-P-I-S-A-L-L-A. CYNTHIA CARR: Your date of birth? JOY EPISALLA: August 17, 1957. CYNTHIA CARR: And where were you born? JOY EPISALLA: Bronxville, New York. CYNTHIA CARR: Oh. Um, so did you grow up there? JOY EPISALLA: No, just happened to be where the hospital was. -

Artists: Ben Frost, Noah Scalin, COPE, Hanksy, Rob Tarbell, David E

“Past to Present” – Artists: Ben Frost, Noah Scalin, COPE, Hanksy, Rob Tarbell, David E. Peterson, Chris Dean, Sangsik Hong. February 7th – March 4th Krause Gallery – www.krausegallery.com 149 Orchard St. NYC Opening Reception: February 7th, 6-9pm NEW YORK — Krause Gallery is excited to announce “Past to Present”, a Group Show. Past To Present showcases the perpetual growth of the artists. Each artist has a piece from their past as well as their present work on display. Growth and evolution in an artists work is necessary for their continual success, without such evolution their work becomes redundant. Ben Frost: (born Brisbane, Australia) is a visual artist whose work seeks to challenge contemporary norms and values of world culture and society. Frost’s visual work places common iconic images from advertising, consumerism, entertainment, and politics into startling juxtapositions that are often confrontational and controversial. He currently lives and works in Sydney, Australia, and exhibits locally and internationally. Frost has been exhibiting throughout Australia and internationally over the last 14 years, including solo shows in London, New York, and San Francisco, as well as group shows in Amsterdam, Berlin, Mongolia, and Singapore. In 2007, Frost participated in Tiger Translate in Beijing, collaborating with local Chinese artists. His work has appeared in countless magazines and newspapers including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Oyster, WeAr, Monster Children, The Sydney Morning. COPE2: Fernando Carlo (also known as Cope2) is an artist from the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx, New York. He has been a graffiti artist since 1978-79, and has gained international credit for his work. -

Food Additives As Important Part of Functional Food

International Research Journal of Biological Sciences ___________________________________ ISSN 2278-3202 Vol. 2(4), 74-86, April (2013) Int. Res. J. Biological Sci. Review Paper Food Additives as Important Part of Functional Food Umida Khodjaeva 1,2 , Tatiana Boj ňanská 1, Vladimír Vietoris 1 , Oksana Sytar 3,4 and Ranjeet Singh 5 1Department of Storing and Processing of Plant Products, University of Agriculture in Nitra, Tr. A. Hlinku 2, 949 76 Nitra, SLOVAKIA 2Department of Nuclear Physics, Samarkand State University, University bulvard 15, 140104 Samarkand, REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN 3Department of Methods of Food Biotechnology, Berlin University of Technology, Institute of Food Technology and Food Chemistry, Königin- Luise Strasse 22, 14195 BERLIN 4Department of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Volodymyrs'ka St. 64, 01601 Kyiv, UKRAINE 5Agro-Produce Processing Division, Central Institute of Agricultural Engineering, Nabi-Bagh, Berasia Road, Bhopal-462 038, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in Received 14 th February 2013, revised 18 th February 2013, accepted 14 th March 2013 Abstract The main characteristics and classification of food additives, which are common in the food production, have been described in the present review. The ways of food additives classification, source of nature, mainly antioxidants, food coloring, flavors, flavor enhancers, bulking agents, stabilizers, sweeteners which were collected from literature based on structural and biochemical characteristics with description of source and possible effects on human, organisms and environment have been presented. Keywords: Food additives, antioxidants, sweeteners, stabilizers, bulking agents, food coloring, flavour enhancers Introduction health benefits (e.g. fortified soy beverages and fruit juices with calcium). -

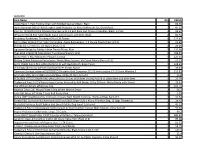

AMAZON Item Name Qty VALUE Cosco Resin 4-Pack Folding Chair

AMAZON Item Name Qty VALUE Cosco Resin 4-Pack Folding Chair with Molded Seat and Back, Black 1 60.45 Home Dynamix DB15D-456 Designer Bath Polyester 15-Piece Bathroom Set, Gray/Black 2 47.12 Sterilite 12229003 Ultra Wheeled Hamper with Lid and Base and Titanium Handles, Black, 3-Pack 2 94.67 Winsome Wood End Table/Night Stand with Drawer and Shelf, Black 2 92.75 Broadway Basketeers Thinking of You Gift Tower 6 222.92 Earth's Best Organic Fruit Yogurt Smoothie, Apple & Blueberry, 4.2 Ounce Pouch (Pack of 12) 1 22.69 Cheribundi Tart Cherry, 32-Ounce (Pack of 3) 1 25.06 Signature Design by Ashley Lilette Throw Pillow, Blue 5 137.56 Char-Broil 12601578 Patio Bistro Tru-Infrared Electric Grill 3 488.25 Graco Pack 'n Play Silhouette Playard, Farrow 1 125.55 Melitta Coffee Filters for Percolators, White Wrap Around, 40-Count Filters (Pack of 12) 1 22.13 Acme 05630 Aston Microfiber Rolled Arm with Back Bench, Beige Finish 1 128.65 Chicology 48-Inch by 64-Inch Florence Roller Shade, Maize 1 39.43 Quantum Storage Systems DG93030CO Dividable Grid Container 22-1/2-Inch Long by 17-1/2-Inch Wide by 3 1 219.82 American Mills 33470.998 Lancelot Pillow, 20 by 20-Inch, Set of 2 1 24.8 PEDIGREE LITTLE CHAMPIONS Meaty Ground Dinner With Beef Variety Pack-8 ct. (With Beef and With Beef 1 25.79 Trademark Fine Art Old Farm House Canvas Artwork by Erik Brede, 16 by 20-Inch, White Matte with Wood 1 43.34 The Official Chicago White Sox Urn 1 503.75 Nautical Decor 24" Wood Pirate's Ship Wheel Marine Decor 2 56.7 Solid Gift Wrap 30" Wide 5 Foot Roll-Pastel Pink 1 -

Dependents Schools (DOD), Washington, D.C

0 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 021 CE 004 768. TITLE Career: Secondary School Career Education. .INSTITUTION Dependents Schools (DOD), Washington, D.C. Pacific Area. PUB DATE Nov 74 NOTE 598p.; Available in Microfiche only due to marginal legibility of original copy. For related elementary school handbook, see CH 004 767 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.08 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Career Education; Classroom Materials; Curriculum Guides; *Instructional Materials; Integrated Curriculum; *Learning Activities; Occupational Clusters; Resource Guides; *Secondary Education; Teacher Developed Materials; *Units of Study (Subject Fields) ABSTRACT The purpose of the handbook isto provide a resource to teachers for integrating career education into secondary level subject areas in order to reveal to students the broad range of career possibilities and the relevance of subject matter to the world of work. The first 19 pages of the document discuss the broad objectives of the program, the articulation of career education goals, and an overview of the program's elements. The remaining 530 pages of the document consist of career education resource packets cf / learning activities for the following subjects: art (20 pages), business education (30 pages), foreign language (6 pages), home 'economics (170 pages), industrial arts (3 pages), language arts (123 pages), music (6 pages), physical education--health and leisure (19 pages), science (63 pages), social studies (67 pages), and transactional analysis (38 pages). Many of the packets include teaching suggestions and objectives and many offer forms, illustration testing, instruments, and resource guides.(BP) ( ********************************************************************** ** DoCument- acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * * materials nof available from other sources.