Asparagine Synthetase Is an Independent Predictor of Surgical Survival and a Potential Therapeutic Target in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism

The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Li, Haoxin, Shaoyang Ning, Mahmoud Ghandi, Gregory V. Kryukov, Shuba Gopal, Amy Deik, Amanda Souza, et. al. 2019. The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism. Nature Medicine 25, no. 5: 850-860. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41899268 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nat Med Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2019 November 08. Published in final edited form as: Nat Med. 2019 May ; 25(5): 850–860. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0404-8. The Landscape of Cancer Cell Line Metabolism Haoxin Li1,2, Shaoyang Ning3, Mahmoud Ghandi1, Gregory V. Kryukov1, Shuba Gopal1, Amy Deik1, Amanda Souza1, Kerry Pierce1, Paula Keskula1, Desiree Hernandez1, Julie Ann4, Dojna Shkoza4, Verena Apfel5, Yilong Zou1, Francisca Vazquez1, Jordi Barretina4, Raymond A. Pagliarini4, Giorgio G. Galli5, David E. Root1, William C. Hahn1,2, Aviad Tsherniak1, Marios Giannakis1,2, Stuart L. Schreiber1,6, Clary B. Clish1,*, Levi A. Garraway1,2,*, and William R. Sellers1,2,* 1Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 2Department -

ASN2 Is a Key Enzyme in Asparagine Biosynthesis Under Ammonium Sufficient Conditions

Plant Biotechnology 26, 153–159 (2009) Original Paper ASN2 is a key enzyme in asparagine biosynthesis under ammonium sufficient conditions Daisuke Igarashi,* Takashi Ishizaki, Kazuhiko Totsuka, Chieko Ohsumi Institute of Life Sciences, Ajinomoto Co., Inc., Kawasaki, Kanagawa 210-8681, Japan * E-mail: [email protected] Tel: ϩ81-44-244-5643 Fax: ϩ81-44-244-9617 Received August 18, 2008; accepted October 30, 2008 (Edited by H. Takahashi) Abstract The modification and enhancement of plant amino acid accumulation is potentially beneficial in terms of the production of suitable crop plants for food or feeds, and also with respect to possible environmental improvement via the effective use of nitrogen nutrition. It is also expected that modified plants will produce beneficial nitrogenous compounds, such as proteins, secondary metabolites, or nucleic acids. The size of amino acid pools in plants is strictly controlled by certain environmental factors such as light and nutrition. In order to gain an understanding of the mechanisms that control amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism, we investigated the diurnal changes in amino acid contents and also how the amino acid contents change with the progression of growth. We observed that almost all the amino acids in plant leaves undergo diurnal changes and that the pattern of these changes was different in young and old stages. We focused on correlation of the asparagine content and the expression of ASN2 asparagine synthetase, since under our experimental conditions their fluctuating patterns were found to be similar. The asparagine contents of ASN2-overexpressing and -underexpressing plants were increased and decreased, respectively, when they were grown under normal light and nutrient conditions. -

Structures, Functions, and Mechanisms of Filament Forming Enzymes: a Renaissance of Enzyme Filamentation

Structures, Functions, and Mechanisms of Filament Forming Enzymes: A Renaissance of Enzyme Filamentation A Review By Chad K. Park & Nancy C. Horton Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 N. C. Horton ([email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-2710-8284) C. K. Park ([email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-1089-9091) Keywords: Enzyme, Regulation, DNA binding, Nuclease, Run-On Oligomerization, self-association 1 Abstract Filament formation by non-cytoskeletal enzymes has been known for decades, yet only relatively recently has its wide-spread role in enzyme regulation and biology come to be appreciated. This comprehensive review summarizes what is known for each enzyme confirmed to form filamentous structures in vitro, and for the many that are known only to form large self-assemblies within cells. For some enzymes, studies describing both the in vitro filamentous structures and cellular self-assembly formation are also known and described. Special attention is paid to the detailed structures of each type of enzyme filament, as well as the roles the structures play in enzyme regulation and in biology. Where it is known or hypothesized, the advantages conferred by enzyme filamentation are reviewed. Finally, the similarities, differences, and comparison to the SgrAI system are also highlighted. 2 Contents INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………..4 STRUCTURALLY CHARACTERIZED ENZYME FILAMENTS…….5 Acetyl CoA Carboxylase (ACC)……………………………………………………………………5 Phosphofructokinase (PFK)……………………………………………………………………….6 -

Did Amino Acid Side Chain Reactivity Dictate the Composition and Timing of Aminoacyl-Trna Synthetase Evolution?

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Did Amino Acid Side Chain Reactivity Dictate the Composition and Timing of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Evolution? Tamara L. Hendrickson *, Whitney N. Wood †,‡ and Udumbara M. Rathnayake †,§ Department of Chemistry, Wayne State University, 5101 Cass Avenue, Detroit, MI 48202, USA; [email protected] (W.N.W.); [email protected] (U.M.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-313-577-6914 † These two authors contributed equally to this manuscript. ‡ Current address: Schmid College of Science and Technology, Chapman University, Orange, CA 92866, USA. § Current address: Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA. Abstract: The twenty amino acids in the standard genetic code were fixed prior to the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). Factors that guided this selection included establishment of pathways for their metabolic synthesis and the concomitant fixation of substrate specificities in the emerging aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs). In this conceptual paper, we propose that the chemical reactivity of some amino acid side chains (e.g., lysine, cysteine, homocysteine, ornithine, homoserine, and selenocysteine) delayed or prohibited the emergence of the corresponding aaRSs and helped define the amino acids in the standard genetic code. We also consider the possibility that amino acid chemistry delayed the emergence of the glutaminyl- and asparaginyl-tRNA synthetases, neither of which are ubiquitous in extant organisms. We argue that fundamental chemical principles played critical roles in fixation of some aspects of the genetic code pre- and post-LUCA. -

Role of Amino Acid Metabolism in Angiogenesis T ⁎ Roxana E

Vascular Pharmacology 112 (2019) 17–23 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vascular Pharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vph Review Role of amino acid metabolism in angiogenesis T ⁎ Roxana E. Oberkersch, Massimo M. Santoro Department of Biology, University of Padua, Italy ABSTRACT The role of endothelial metabolism represents a crucial element governing the formation and the differentiation of blood vessels, termed angiogenesis. Besides glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation, endothelial cells rely on specific amino acids to proliferate, migrate, and survive. In this review we focus on the metabolism of those amino acids and the intermediates that hold an established function within angiogenesis and endothelial pa- thophysiology. We also discuss recent work which provides a rationale for specific amino acid-restricted diets and its beneficial effects on vascular tissues, including extending the life span and preventing the development of a variety of diseases. 1. Introduction and produce up to 85% of their ATP through aerobic glycolysis [5]. It has been hypothesized that the use of glycolysis as the main source of The vascular system is a multi-branched network lined by en- ATP holds several advantages. High glycolytic flux can produce faster dothelial cells (ECs) which delivers oxygen and nutrients to the tissues ATP with respect to oxidative metabolism, which represents an ad- in the body [1]. The ability to expand this network is a process called vantage for ECs in a hypoxic microenvironment [6]. The anaerobic angiogenesis. This process is vital in many physiological settings and is metabolism of ECs might save oxygen towards becoming perivascular also implicated in the pathogenesis of several disorders including: mural cells [7]. -

Chemistry of Molecular Biocatalysts –

Division of Biochemistry – Chemistry of Molecular Biocatalysts – http://www.scl.kyoto-u.ac.jp/~hiratake/index-j.html Prof Assist Prof Assist Prof HIRATAKE, Jun WATANABE, Bunta KOEDUKA, Takao (D Agr) (D Agr) (D Agr) Students KAWANISHI, Daisuke (M2) JING, Dongyu (M2) YIN, Ziwei (RS) LI, Chunjie (M2) OZAKI, Ayane (M1) Scope of Research Our research focuses on the molecular design and synthesis of specific inhibitors of physiologically important enzymes (biocatalysts). The enzyme inhibitors are used for probing the reaction mechanisms, three-dimensional structures and identifying the physiological roles of the enzymes. The finely designed inhibitors are further elaborated to develop useful bioactive substances that could knockout the specific enzyme in vivo to develop lead compounds for novel pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals and cosmetic ingredients. Our current research includes the design, synthesis and applications of transition-state analogue and/or mechanism-based inhibitors of such enzymes as γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, a key enzyme in glutathione metabolism, asparagine synthetase, an important enzyme for cancer chemotherapy, and 4-coumaroyl CoA ligase that plays a pivotal role in the biosynthesis of a vast array of phenylpropanoid in plants. The identification of the genes of hitherto unknown enzymes for biosynthesis of phenylpropanoid volatiles in plants are also pursued to shed light on the detailed reaction mechanisms and the physiological function of the biosynthetic enzymes in plant secondary metabolites. KEYWORDS Enzyme Reaction Mechanisms Transition-State Analogue Inhibitors Mechanism-Based Enzyme Inhibitors Glutathione Homeostasis Bioactive Substance Selected Publications Ida, T.; Suzuki, H.; Fukuyama, K.; Hiratake, J.; Wada, K., Crystal Structure of Bacillus subtilis γ-glutamyltranspeptidase in Complex with Acivicin: Diversity of the Binding Mmode of a Classical and Electrophilic Active-site Directed Glutamate Analogue, Acta Crystallogr. -

Metabolic Network-Based Stratification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Reveals Three Distinct Tumor Subtypes

Metabolic network-based stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma reveals three distinct tumor subtypes Gholamreza Bidkhoria,b,1, Rui Benfeitasa,1, Martina Klevstigc,d, Cheng Zhanga, Jens Nielsene, Mathias Uhlena, Jan Borenc,d, and Adil Mardinoglua,b,e,2 aScience for Life Laboratory, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, SE-17121 Stockholm, Sweden; bCentre for Host-Microbiome Interactions, Dental Institute, King’s College London, SE1 9RT London, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Molecular and Clinical Medicine, University of Gothenburg, SE-41345 Gothenburg, Sweden; dThe Wallenberg Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, SE-41345 Gothenburg, Sweden; and eDepartment of Biology and Biological Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, SE-41296 Gothenburg, Sweden Edited by Sang Yup Lee, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, and approved November 1, 2018 (received for review April 27, 2018) Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most frequent forms of of markers associated with recurrence and poor prognosis (13–15). liver cancer, and effective treatment methods are limited due to Moreover, genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), collections tumor heterogeneity. There is a great need for comprehensive of biochemical reactions, and associated enzymes and transporters approaches to stratify HCC patients, gain biological insights into have been successfully used to characterize the metabolism of subtypes, and ultimately identify effective therapeutic targets. We HCC, as well as identify drug targets for HCC patients (11, 16–18). stratified HCC patients and characterized each subtype using tran- For instance, HCC tumors have been stratified based on the uti- scriptomics data, genome-scale metabolic networks and network lization of acetate (11). Analysis of HCC metabolism has also led topology/controllability analysis. -

Effect of Acinetobacter Glutaminase-Asparaginase Treatment on Free Amino Acids in Mouse Tissues1

[CANCER RESEARCH 35. 1320 1325. May 1975] Effect of Acinetobacter Glutaminase-Asparaginase Treatment on Free Amino Acids in Mouse Tissues1 John S. Holcenberg, Esther Tang, and William C. Dolowy Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology. University of Washington School of Medicine. Seattle. Washington 9X195 [J. S. H.. E. T.}. and Chicago Medical School and Hiñes Vêlerons Administration Hospital. Chicago. Illinois 60612 [W. C. D.] SUMMARY LDH virus-infected mice (26) and are confined largely to the vascular space. As expected from these considerations, Acinetobacier glutaminase-asparaginase (AGA) and treatment of mice and humans with EC-2 produces pro Escherichia coli asparaginase were compared for their longed depletion of plasma asparagine but only transient effects on plasma and tissue levels of amino acids, am depletion of plasma glutamine (21, 25). AGA treatment in monia, and glutamyl transferase activity in the mouse. Free mice produces prolonged depletion of both plasma aspara asparagine was depleted similarly in plasma and tissues by gine and glutamine (26). both enzymes. AGA treatment produced partial depletion Several studies have reported changes in free amino acids of glutamine concentrations in muscle, spleen, small intes in tissues during treatment with asparaginase enzymes, but tine, and liver. Brain and kidney glutamine concentrations none of these enzymes has had appreciable glutaminase actually rose with treatment. Despite over 100-fold increase activity under physiological conditions (2, 7, 20, 30). The in plasma glutamate, only the kidney showed a substantial amino acid levels in tissues should depend on the delivery of increase in free glutamate levels during AGA treatment. substrates and enzymes by the vascular system, together Glutamine biosynthesis measured by glutamyl transferase with the rate of synthesis and utilization of the amino acid in activity showed an appreciable increase only in the kidney. -

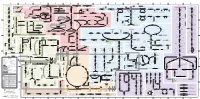

Fullsubwaymap221.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M Aldose reductase Sorbitol dehydrogenase Cholesterol synthesis Glycogen and galactose metabolism (branch point only) (debranching) glucose sorbitol fructose Aromatic amino acid metabolism Purine synthesis Pyrimidine synthesis glycogen (n+1) phenylacetate triiodothyronine (T3) dopaquinone melanin + + thyroxine (T4) (multiple steps) (many cycles) P 4' NADPH NADP NAD NADH acetyl-CoA x2 i Debranching enzyme 3' - α-1,4 bonds Aromatic amino acid 5-phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) HCO B 2' P 3 (branching) Glycogen 6 i (multiple steps) O H O (multiple steps) Tyrosinase O H O 1' 2 2 2 2 B 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pentose phosphate pathway Phenylalanine Tyrosine decarboxylase 6 Dopamine B Thiolase phosphorylase -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 Transaminase 6 glutamine 2 ATP (many cycles) Glycogen Glucose-6-phosphatase Dehydrogenase hydroxylase hydroxylase (DOPA decarboxylase) β-hydroxylase Methyltransferase 10 UDP 4:4 Transferase ATP glutathione (reduced) H O phenyllactate phenylpyruvate phenylalanine tyrosine dihydroxy- dopamine Glutamine PRPP CoA synthase Hexokinase or (in endoplasmic reticulum) 2 2 norepinephrine epinephrine glutamine Carbamoyl 9 1' phenylanine amidotransferase (GPAT) glutamate glycogen (n) Glutathione reductase Glutathione peroxidase + phosphate glycogen (n) -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 2' 3' 4' glucokinase 8 NADP NADPH glutamate α-ketoglutarate CO2 O H O Glycosyl (4:6) UDP-glucose ADP (L-DOPA) 2 2 synthetase II glutathione (oxidized) 2 H O α-ketoglutarate PPi glutamate acetoacetyl-CoA 7 1 Glucose -1,6-Glucosidase -

A Role for Asparaginyl-Trna in the Regulation of Asparagine Synthetase in a Mammalian Cell Line

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 74, No. 6, pp. 2367-2369, June 1977 Biochemistry A role for asparaginyl-tRNA in the regulation of asparagine synthetase in a mammalian cell line (Chinese hamster ovary cells/asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase/temperature-sensitive mutant/gene expression) STUART M. ARFIN*, DONALD R. SIMPSONt, C. S. CHIANGt, IRENE L. ANDRULIS*, AND G. WESLEY HATFIELDt Departments of *Biological Chemistry and tMedical Microbiology, College of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California 92717 Communicated by H. E. Umbarger, March 31, 1977 ABSTRACT The expression of asparagine synthetase ac- MATERIALS AND METHODS tivity [L-aspartate:ammonia ligase (AMP-forming), EC 6.3.1.1] in cultured Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells is regulated by Growth of Cells. CHO-KI cells, obtained from the American asparagine. After transfer of CHO cells from an asparagine- Type Culture Collection, and PSV1 cells, the generous gift of supplemented medium to a medium lacking asparagine, activity L. H. Thompson, were grown as monolayers in an atmosphere increases 1.5- to 2-fold. If asparagine is added back to the me- of 5% C02/95% air. The basal media employed were a-MEM dium, activity returns to control levels. To test the possible in- (6) (K-C Biologicals) containing 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum volvement of Asn-tRNA~sn in regulating the levels o asparagine synthetase, we have examined the levels of asparagine synthe- (Gibco) and Ham's F-10 (7) containing 10% dialyzed calf serum tase in a mutant of CHO cells containing a temperature-sensitive and 5% dialyzed fetal calf serum. asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase [L-asparagine:tRNA ligase Preparation of Cell Extracts. -

Asparagine: a Metabolite to Be Targeted in Cancers

H OH metabolites OH Review Asparagine: A Metabolite to Be Targeted in Cancers Jie Jiang 1, Sandeep Batra 2,* and Ji Zhang 1,3,* 1 Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA; [email protected] 2 Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health; Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA 3 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Medicine, Indiana University; Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (J.Z.) Abstract: Amino acids play central roles in cancer progression beyond their function as building blocks for protein synthesis. Thus, targeting amino acid acquisition and utilization has been proved to be therapeutically beneficial in various pre-clinical models. In this regard, depletion of circulating asparagine, a nonessential amino acid, by L-asparaginase has been used in treating pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) for decades. Of interest, unlike most solid tumor cells, ALL cells lack the ability to synthesize their own asparagine de novo effectively. However, only until recently, growing evidence suggests that solid tumor cells strive to acquire adequate amounts of asparagine to support tumor progression. This process is subjected to the regulation at various levels, including oncogenic signal, tumor-niche interaction, intratumor heterogeneity and dietary accessibility. We will review the literature on L-asparaginase-based therapy as well as recent understanding of asparagine metabolism in solid tumor progression, with the hope of shedding light into a broader cancer therapeutic strategy by perturbing its acquisition and utilization. Keywords: asparagine; L-asparaginase; acute lymphoblastic leukemia; asparagine synthetase; stress Citation: Jiang, J.; Batra, S.; Zhang, J. -

Asparagine Synthetase Deficiency

Asparagine synthetase deficiency Description Asparagine synthetase deficiency is a condition that causes neurological problems in affected individuals starting soon after birth. Most people with this condition have an unusually small head size (microcephaly) that worsens over time due to loss (atrophy) of brain tissue. They also have severe developmental delay that affects both mental and motor skills (psychomotor delay). Affected individuals cannot sit, crawl, or walk and are unable to communicate verbally or nonverbally. The few affected children who achieve developmental milestones often lose these skills over time (developmental regression). Most individuals with asparagine synthetase deficiency have exaggerated reflexes ( hyperreflexia) and weak muscle tone (hypotonia). The muscle problems worsen through childhood and lead to muscle stiffness, uncontrolled movements, and ultimately, paralysis of the arms and legs (spastic quadriplegia). Many affected individuals also have recurrent seizures (epilepsy). Not all affected people experience the same type of seizure. The most common types involve a loss of consciousness, muscle rigidity, and convulsions (tonic-clonic); involuntary muscle twitches (myoclonic); or abnormal muscle contraction (tonic). People with asparagine synthetase deficiency may have an exaggerated startle reaction (hyperekplexia) to unexpected stimuli. Some affected individuals have blindness due to impairment of the area of the brain responsible for processing vision, called the occipital cortex (cortical blindness). People with asparagine synthetase deficiency typically do not survive past childhood. Frequency Asparagine synthetase deficiency is thought to be a rare condition. More than 20 affected individuals have been described in the medical literature. Causes Asparagine synthetase deficiency is caused by mutations in a gene called ASNS. This gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called asparagine synthetase.