Crafting Symbolic Geographies in Modern Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

Iraq and the Kurds: the Brewing Battle Over Kirkuk

IRAQ AND THE KURDS: THE BREWING BATTLE OVER KIRKUK Middle East Report N°56 – 18 July 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. COMPETING CLAIMS AND POSITIONS................................................................ 2 A. THE KURDISH NARRATIVE....................................................................................................3 B. THE TURKOMAN NARRATIVE................................................................................................4 C. THE ARAB NARRATIVE .........................................................................................................5 D. THE CHRISTIAN NARRATIVE .................................................................................................6 III. IRAQ’S POLITICAL TRANSITION AND KIRKUK ............................................... 7 A. USES OF THE KURDS’ NEW POWER .......................................................................................7 B. THE PACE OF “NORMALISATION”........................................................................................11 IV. OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS................................................................ 16 A. THE KURDS.........................................................................................................................16 B. THE TURKOMANS ...............................................................................................................19 -

A Study of European, Persian, and Arabic Loans in Standard Sorani

A Study of European, Persian, and Arabic Loans in Standard Sorani Jafar Hasanpoor Doctoral dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Iranian languages presented at Uppsala University 1999. ABSTRACT Hasanpoor, J. 1999: A Study of European, Persian and Arabic Loans in Standard Sorani. Reports on Asian and African Studies (RAAS) 1. XX pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-506-1353-7. This dissertation examines processes of lexical borrowing in the Sorani standard of the Kurdish language, spoken in Iraq, Iran, and the Kurdish diaspora. Borrowing, a form of language contact, occurs on all levels of language structure. In the pre-standard literary Kurdish (Kirmanci and Sorani) which emerged in the pre-modern period, borrowing from Arabic and Persian was a means of developing a distinct literary and linguistic tradition. By contrast, in standard Sorani and Kirmanci, borrowing from the state languages, Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, is treated as a form of domination, a threat to the language, character, culture, and national distinctness of the Kurdish nation. The response to borrowing is purification through coinage, internal borrowing, and other means of extending the lexical resources of the language. As a subordinate language, Sorani is subjected to varying degrees of linguistic repression, and this has not allowed it to develop freely. Since Sorani speakers have been educated only in Persian (Iran), or predominantly in Arabic, European loans in Sorani are generally indirect borrowings from Persian and Arabic (Iraq). These loans constitute a major source for lexical modernisation. The study provides wordlists of European loanwords used by Hêmin and other codifiers of Sorani. -

Prospects for Political Inclusion in Rojava and Iraqi Kurdistan

ISSUE BRIEF 09.05.18 False Hopes? Prospects for Political Inclusion in Rojava and Iraqi Kurdistan Mustafa Gurbuz, Ph.D., Arab Center, Washington D.C. Among those deeply affected by the Arab i.e., unifying Kurdish cantons in northern Spring were the Kurds—the largest ethnic Syria under a new local governing body, is minority without a state in the Middle depicted as a dream for egalitarianism and East. The Syrian civil war put the Kurds at a liberal inclusive culture that counters the forefront in the war against the Islamic patriarchic structures in the Middle East.1 State (IS) and drastically changed the future U.S. policy toward the Kurds, however, prospects of Kurds in both Syria and Iraq. has become most puzzling since the 2017 This brief examines the challenges that defeat of IS in Syria. While the U.S.—to hinder development of a politically inclusive avoid alienating the Turks—did not object culture in Syrian Kurdistan—popularly to the Turkish troops’ invasion of the known as Rojava—and Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurdish canton of Afrin, the YPG began Political and economic instability in both forging closer ties to Damascus—which regions have shattered Kurdish dreams for led to complaints from some American political diversity and prosperity since the officials that the Kurdish group “has turned early days of the Arab Spring. into an insurgent organization.”2 In fact, from the beginning of the Syrian civil war, Syrian Kurds have been most careful to not THE RISING TIDE OF SYRIAN KURDS directly target the Assad regime, aside from some short-term clashes in certain places The civil war in Syria has thus far bolstered like Rojava, for two major reasons. -

Turkification of the Toponyms in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey*

TURKIFICATION OF THE TOPONYMS IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE AND THE REPUBLIC OF TURKEY* Sahakyan L. S. PhD in Philology ABSTRACT Toponyms represent persistent linguistic facts, which have major historical and political significance. The rulers of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey realized the strategic importance of the toponyms and carried out consistent policies towards their distortion and appropriation. Aiming to assimilate the toponyms of the newly conquered territories, the Ottoman authorities translated them into Turkish from their original languages or transformed the local dialect place-names by the principle of contamination to make them sound like Turkish word-forms. Other methods of appropriation included the etymological misinterpretation and renaming and displacing the former toponyms altogether. The focus of the present article is the place-name transformation policies of the Ottoman Empire and its successor, the Republic of Turkey. The decree by the Minister of War Enver Pasha issued on January 5, 1916 with the orders to totally change the “non-Muslim” place-names is for the first time presented in English, Armenian and Russian translations. The article also deals with the artificially created term of “Eastern Anatolia” as an ungrounded, politicized substitute for Western Armenia, the political objectives of the pro-Turkish circles as well as the consequences of putting the mentioned ersatz term into circulation. In August 2009, during his visit to Bitlis, in the District of Bitlis (a formerly Armenian city Baghesh in the south-western part of Western Armenia), Turkish President Abdullah Gul said publicly that the original name of the present-day Gyouroymak province was “Norshin”, which, he claimed, was in Kurdish.1 This statement should not be considered as a slip of the tongue; it represents traditional Turkish policies of Turkification and Kurdification of original Armenian toponyms. -

From Qamishli to Qamishlo: a Trip to Rojava's New Capital

MENU Policy Analysis / Fikra Forum From Qamishli to Qamishlo: A Trip to Rojava’s New Capital by Fabrice Balanche May 8, 2017 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Fabrice Balanche Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is an adjunct fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis M ay 8, 2017 I had not been to Qamishli for twenty years. As a Ph.D. student at the French Institute for the Near East, I went with two friends in the late 1990s to explore northeast Syria. This journey led us to Raqqa, Deir al-Zour, Hasaka, and Qamishli. Since 1997 I have returned to other Syrian cities on several occasions but did not have the opportunity to go to Rojava. Twenty years ago, I stayed in the venerable Semiramis Hotel. This luxurious Art Deco hotel was built in the 1950s, the ‘’Golden Age’’ of Jazira when Qamishli was the economic center of this rich grain and cotton producing area. The Semiramis welcomed the tradesmen, textile merchants, and millers of Aleppo who came to buy crops, and the restaurant hosted the high society of Qamishli who came to taste French wines and eat filet mignon. The city was mainly Christian, the rural exodus having not yet engulfed Qamishli. The Armenian and Syriac populations had fled Turkey for France after the First World War, and the French installed them in this almost empty region in order to limit the land claims of Mustafa Kemal in northern Syria. The Christians made the desert bloom using the land that was granted to them by the authorities. -

Full Book PDF Download

nachmani [26.5].jkt 27/5/03 4:13 pm Page 1 Europeinchange E K T C facing a Turkey: new millennium ✭ Turkey’s involvement in the Gulf War in 1991 indirectly helped to pave the way for the country’s invitation almost a decade later to negotiate its accession into the European Union. This book traces that process and in the first part looks at Turkey’s foreign policy in the 1990s, considering the ability of the country to withstand the repercussions of the fall of communism. It focuses on Turkey’s achievement in halting and minimising the effects of the temporary devaluation in its strategic importance that resulted from the waning of the Cold War and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. It emphasizes the skilful way in which Turkey avoided becoming embroiled in the ethnic and international upheavals in Central Asia, the Balkans, the east-Mediterranean and the Middle East, and the ✭ change change development of a continued policy of closer integration into the European and western worlds. nachmani Turkey: facing Internal politics are the focus of the second part of the book, addressing in the curbing of the Kurdish revolt, the economic gains made, and the in a new millennium strengthening of civil society. Nachmani goes on to analyse the prospects for Turkey in the twenty-first century, in the light of the possible integration into Europe, which may leave the country’s leadership free to Coping with deal effectively with domestic issues. intertwined conflicts This book will make crucial reading for anyone studying Turkish politics, or indeed European or European Union politics. -

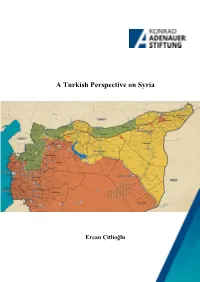

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Vincent Doix 2013 Memoire.Pdf

Université de Montréal Les difficultés d’application du droit international au conflit du Haut-Karabagh : effectivités et causes géopolitiques Par Vincent DOIX Faculté de Droit Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise en droit international, option recherche Directrice de mémoire : Madame le professeur Suzanne LALONDE Septembre 2012 © Vincent Doix, 2012 Résumé Conflit présenté comme gelé, la guerre du Haut-Karabagh n’en est pas moins réelle, s’inscrivant dans une géopolitique régionale complexe et passionnante, nécessitant de s’intéresser à l’histoire des peuples de la région, à l’histoire des conquêtes et politiques menées concomitamment. Comprendre les raisons de ce conflit situé aux limites de l’Europe et de l’Asie, comprendre les enjeux en cause, que se soit la problématique énergétique ou l’importance stratégique de la région du Caucase à la fois pour la Russie mais également pour les Etats-Unis ou l’Union Européenne ; autant de réflexions que soulève cette recherche. Au delà, c’est l’influence réciproque du droit international et du politique qui sera prise en compte, notamment concernant l’échec des négociations actuelles. Les difficultés d’application du droit international à ce conflit sui generis se situent à plusieurs niveaux ; sur le statut de la région principalement, mais également sur les mécanismes de sanctions et de réparations devant s’appliquer aux crimes sur les personnes et les biens et qui se heurtent à la classification difficile du conflit. Mots clés Arménie, Azerbaïdjan, Caucase, conflit, droit à l’autodétermination, droit international, énergie, Haut-Karabagh, intégrité territoriale, minorités, droit international humanitaire. -

Imagined Kurds

IMAGINED KURDS: MEDIA AND CONSTRUCTION OF KURDISH NATIONAL IDENTITY IN IRAQ A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for / \ 5 the Degree 3C Master of Arts In International Relations by Miles Theodore Popplewell San Francisco, California Fall 2017 Copyright by Miles Theodore Popplewell 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Imagined Kurds by Miles Theodore Popplewell, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in International Relations at San Francisco State University. Assistant Professor Amy Skonieczny, Ph.D. Associate Professor IMAGINED KURDS Miles Theodore Popplewell San Francisco, California 2017 This thesis is intended to answer the question of the rise and proliferation of Kurdish nationalism in Iraq by examining the construction of Kurdish national identity through the development and functioning of a mass media system in Iraqi Kurdistan. Following a modernist approach to the development and existence of Kurdish nationalism, this thesis is largely inspired by the work of Benedict Anderson, whose theory of nations as 'imagined communities' has significantly influenced the study of nationalism. Kurdish nationalism in Iraq, it will be argued, largely depended upon the development of a mass media culture through which political elites of Iraqi Kurdistan would utilize imagery, language, and narratives to develop a sense of national cohesion amongst their audiences. This thesis explores the various aspects of national construction through mass media in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, in mediums such as literature, the internet, radio, and television. -

Whose Kurdistan? Class Politics and Kurdish Nationalism in the Middle East, 1918-2018

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Whose Kurdistan? Class Politics and Kurdish Nationalism in the Middle East, 1918-2018 Nicola Degli Esposti A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, 13 September 2020 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,640 words. 2 Abstract This thesis is a study of the different trajectories of Kurdish nationalism in the Middle East. In the late 2010s – years of momentous advance for Kurdish forces in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria – Kurdish politics was deeply divided into competing movements pursuing irreconcilable projects for the future of the Kurdish nation. By investigating nationalism as embedded in social conflicts, this thesis identifies in the class basis of Kurdish movements and parties the main reason for their political differentiation and the development of competing national projects. After the defeat of the early Kurdish revolts in the 1920s and 1930s, Kurdish nationalism in Iraq and Turkey diverged along ideological lines due to the different social actors that led the respective national movements. -

American Women's Foreign Mission Movement

THE ORIGINAL TURKISH CONCERNS ABOUT DEVELOPMENTS IN NORTHERN IRAQ A Master‟s Thesis by KWANGSOO CHOI Department of International Relations Bilkent University Ankara May 2008 THE ORIGINAL TURKISH CONCERNS ABOUT DEVELOPMENTS IN NORTHERN IRAQ The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University By KWAGNSOO CHOI In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTERS OF ARTS In THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA May 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Masters of Arts in International Relations. ------------------------------ Assistant Professor Mustafa Kibaroğlu Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Masters of Arts in International Relations. ------------------------------ Assistant Professor H. Tarık Oğuzlu Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Masters of Arts in International Relations. ------------------------------ Associate Professor Jeremy Salt Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences ------------------------------ Prof. Erdal Erel Director ii ABSTRACT THE ORGINAL TURKISH CONCERNS ABOUT DEVELOPMENTS IN NORTNERN IRAQ Choi, Kwangsoo M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Mustafa Kibaroğlu May 2008 After the invasion of Iraq by the U.S., Iraq is undergoing significant transition that no one can predict the future perfectly. Such changes in Iraq will lead to the increasing concerns from neighboring countries including Turkey, Iran, and Arab states.