07 Part Two Chapter 9 Everett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

04 Part Two Chapter 4-5 Everett

PART TWO. "So what are you doing now?" "Well the school of course." "You mean youre still there?" "Well of course. I will always be there as long as there are students." (Jacques Lecoq, in a letter to alumni, 1998). 79 CHAPTER FOUR INTRODUCTION TO PART TWO. The preceding chapters have been principally concerned with detailing the research matrix which has served as a means of mapping the influence of the Lecoq school on Australian theatre. I have attempted to situate the research process in a particular theoretical context, adopting Alun Munslow's concept of `deconstructionise history as a model. The terms `diaspora' and 'leavening' have been deployed as metaphorical frameworks for engaging with the operations of the word 'influence' as it relates specifically to the present study. An interpretive framework has been constructed using four key elements or features of the Lecoq pedagogy which have functioned as reference points in terms of data collection, analysis and interpretation. These are: creation of original performance material; use of improvisation; a movement-based approach to performance; use of a repertoire of performance styles. These elements or `mapping co-ordinates' have been used as focal points during the interviewing process and have served as reference points for analysis of the interview material and organisation of the narrative presentation. The remainder of the thesis constitutes the narrative interpretation of the primary and secondary source material. This chapter aims to provide a general overview of, and introduction to the research findings. I will firstly outline a demographic profile of Lecoq alumni in Australia. Secondly I will situate the work of alumni, and the influence of their work on Australian theatre within a broader socio-cultural, historical context. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

Teacher's Notes 2007

Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Festival in association with Perth International Festival present the STC Actors Company in The War of the Roses by William Shakespeare Teacher's Resource Kit Part One written and compiled by Jeffrey Dawson Acknowledgements Thank you to the following for their invaluable material for these Teachers' Notes: Laura Scrivano, Publications Manager,STC; Tom Wright, Associate Director, STC Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Sydney Theatre Company The Wars of the Roses Teachers Notes © 2009 1 Contents Production Credits 3 Background information on the production 4 Part One, Act One Backstory & Synopsis 5 Part One, Act Two Backstory & Synopsis 5 Notes from the Rehearsal Room 7 Shakespeare’s History plays as a genre 8 Women in Drama and Performance 9 The Director – Benedict Andrews 10 Review Links 11 Set Design 12 Costume Design 12 Sound Design 12 Questions and Activities Before viewing the Play 14 Questions and Activities After viewing the Play 20 Bibliography 24 Background on Part Two of The War of the Roses 27 Sydney Theatre Company The Wars of the Roses Teachers Notes © 2009 2 Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Festival in association with Perth International Festival present the STC Actors Company in The War of the Roses by William Shakespeare Cast Act One King Richard II Cate Blanchett Production -

Neil Armfield

Mr Neil Armfield The honorary degree of Doctor of Letters was conferred upon Neil Armfield at the Faculty of Arts graduation ceremony held at 4.00pm on 21 April 2006. Neil Armfield, photo, courtesy UniNews. Citation Professor Masters, I have the honour to present Neil Armfield for admission to the degree of Doctor of Letters (honoris causa). While Neil Armfield is still only at the midpoint of his brilliant career, he has already made a distinctive contribution to the Arts and Humanities, especially through his work as a director of plays, operas and films, both within Australia and overseas. Neil was born in Sydney and is a graduate of this University, completing his Bachelor of Arts with Honours in English in 1977. While at university he began directing plays for Sydney University Dramatic Society, with such success that he was invited to direct his first professional production for the Nimrod Theatre Company in 1979. This production of David Allen’s Upside Down at the Bottom of the World, a new play about D H Lawrence in Australia, was also a great success and the production was subsequently invited to the 1980 Edinburgh Festival. Neil Armfield became artistic co-director of the Nimrod Theatre Company from 1980-82, confirming his special affinity for new Australian plays with landmark productions of Stephen Sewell’s Traitors and Welcome the Bright World and Louis Nowra’s Inside the Island. In 1983 he was appointed associate director of the Lighthouse Company in Adelaide. He is, however, most strongly associated with the work of Sydney’s Belvoir Street Theatre, having been a member of Company B since its inception in 1984. -

Annual Report 2014 1

Annual Report 2014 1 2 3 4 6 5 7 Cover photographs 1 Paul Bishop in Australia Day 2 Candy Bowers in The Mountaintop 3 Jason Klarwein and Veronica Neave in Macbeth 4 Anna McGahan in The Effect 5 Christen O’Leary in Gloria 6 Promotional photograph for Black Diggers 7 Steven Rooke in Gasp! Photography: Aaron Tait, Branco Gaica (Black Diggers) Illustration: Lauren Marriott (The Mountaintop) Letter to Minister 27 March 2015 The Honourable Annastacia Palaszczuk MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Level 15, Executive Building 100 George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Premier I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2014 and audited financial statements for the Queensland Theatre Company. I certify that this annual report complies with: the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on page 90 of this annual report or accessed at http://www.queenslandtheatre.com.au/About-Us/Publications Yours sincerely, Professor Richard Fotheringham Chair Queensland Theatre Company Queensland Theatre Company Annual Report 1 2 Queensland Theatre Company Annual Report Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... -

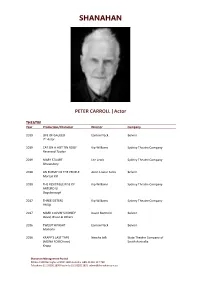

PETER CARROLL |Actor

SHANAHAN PETER CARROLL |Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2019 LIFE OF GALILEO Eamon Flack Belvoir 7th Actor 2019 CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Reverend Tooker 2019 MARY STUART Lee Lewis Sydney Theatre Company Shrewsbury 2018 AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Morton Kiil 2018 THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company ARTURO UI Dogsborough 2017 THREE SISTERS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Phillip 2017 MARK COLVIN’S KIDNEY David Berthold Belvoir David, Bruce & Others 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT Eamon Flack Belvoir Malvolio 2016 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of (MONA FOMO tour) South Australia Krapp Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 SEVENTEEN Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Tom 2015 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of Krapp South Australia 2014 CHRISTMAS CAROL Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Marley and Other 2014 OEDIPUS REX Adena Jacobs Belvoir Oedipus 2014 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTIAN Matthew Lutton Malthouse Theatre Mr Hugo Sword 2012-13 CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG Roger Hodgman TML Enterprises Grandpa Potts 2012 OLD MAN Anthea Williams B Sharp Belvoir (Downstairs) Albert 2011 NO MAN’S LAND Michael Gow QTC/STC Spooner 2011 DOCTOR ZHIVAGO Des McAnuff Gordon Frost Organisation Alexander 2010 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Stuart Maunder Opera Australia Major-General Stanley 2010 KING LEAR Marion Potts Bell -

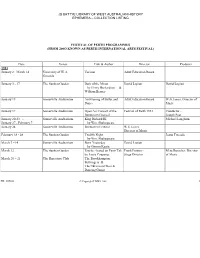

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A. -

Wagner Quarterly 130 September 2013

WAGNER SOCIETY nsw ISSUE NO 3 CELEBRATING THE MUSIC OF RICHARD WAGNER WAGNER QUARTERLY 130 SEPTEMBER 2013 IN MEMORIAM Joseph Ferfoglia (c. 1923-2012) – long-time honorary auditor for the Society – see Swan Lines. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Welcome to the third Wagner Quarterly for 2013. I have to confess that I have missed some of our Society’s more recent events, as I have taken my Wagner enthusiasm overseas. I am really sorry not to have attended these events, as on all accounts they have been outstandingly successful. Some fifty people, including her Excellency the Governor, attended the Dutchman seminar. This is described later in this Quarterly, as are the Lisa Gasteen meeting, the “Swords and Winterstorms” concert, and the more recent Neil Armfield talk, which I believe was fascinating. In June this year, I was fortunate enough to attend Ring Cycles in Riga, Milan and Longborough. And in August I went to the third and last cycle of the new Ring production Multiple multi-coloured Masters by Ottmar Hörl capering over in Bayreuth. Unfortunately, because of the decisions relating Bayreuth: Is he welcoming visitors or shooing us away? 300€ at to ticket allocations, there were many fewer Sydneysiders www.Bayreuth-shop.de in Bayreuth than in previous years. But a small ray of hope on this issue remains. In November the matter will again be The Riga Opera House is a jewel of a 19th century opera discussed at a meeting house at one end of a park which divides the mediaeval of the Administrative section of the city from the modern city. -

2021 Season Brochure

Our Town By Thornton Wilder 30 Jan — 27 Feb Bille Brown Theatre Triple X By Glace Chase 6 Mar — 1 Apr Bille Brown Theatre Taming of the Shrew By William Shakespeare 8 May — 12 Jun Bille Brown Theatre White Pearl By Anchuli Felicia King 17 Jun — 10 Jul Bille Brown Theatre Prima Facie By Suzie Miller 14 Jul — 14 Aug Bille Brown Theatre Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe Adapted for the stage by Tim McGarry 30 Aug — 18 Sep Playhouse, QPAC Return to the Dirt By Steve Pirie 16 Oct — 13 Nov Bille Brown Theatre SPECIAL EVENT Robyn Archer: An Australian Songbook Devised and performed by Robyn Archer 20 Nov — 4 Dec Bille Brown Theatre 3 We have all been on a wild ride in 2020 and 2021 promises to be challenging in ways we cannot imagine. But imagine we will. Together. Because we have all learned how much we need theatre. We need to see great big We need the buzz of a stories that fill us with foyer. inspiration. We need dates in our We need laughter and love calendars to look forward and ideas and provocations to. and magic. We need our culture to We need to have our artists come back to life. back at work breathing life None of us imagine it will into the national imagination. be easy. We need to talk to friends But we have to try. about the play we all saw last night and disagree with them Because we have lived about what it really meant. a time without theatre, and I don’t know about We need Australian voices you but I don’t want to speaking to us about what imagine a future without matters to us right now. -

1 Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2014

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2014 1 Kate Box, Melita Jurisic, Robert Menzies, Hugo Weaving, Ivan Donato, Eden Falk, Paula Arundell and John Gaden in Macbeth. Photo: Brett Boardman Aims of the Company To provide first class theatrical entertainment for the people of Sydney – theatre that is grand, vulgar, intelligent, challenging and fun. That entertainment should reflect the society in which we live thus providing a point of focus, a frame of reference, by which we come to understand our place in the world as individuals, as a community and as a nation. Richard Wherrett, 1980 Founding Artistic Director 5 2014 in Numbers ACTORS AND CREATIVES 237 EMPLOYED $350,791 C R 12TEACHING TIX OF TI KET P ICE TIX SAVINGS PASSED ON TO ARTISTS 733 4,877 SUNCORP TWENTIES CUSTOMERS EMPLOYED REGIONAL $20.834M AND INTERSTATE TOTAL TICKET PERFORMANCES INCOME EARNED WORLD 6PREMIERES 1,187 WEEKS PLAYWRIGHTS AVERAGE OF WORK 9 ON COMMISSION CAPACITY FOR ACTORS 6 7 David Gonski Andrew Chairman Upton In the last four annual reports, I have reported on work undertaken by the organisation to modernise operations and governance structures to best support the Company’s artistic aspirations into the Artistic Director future. Most recently, in 2013, I wrote about the security of 45 year leases over the Roslyn Packer Theatre (formerly Sydney Theatre) and James Duncan in The Long Way Home. Richard Roxburgh in Cyrano de Bergerac. our tenancy at The Wharf, and the subsequent winding up of New Photo: Lisa Tomasetti 2014 was a year that brought the Company together through thick Photo: Brett Boardman South Wales Cultural Management, the body that had previously and thin. -

Rocky Horror Show Is Back

A BRAND SPANKING NEW PRODUCTION iOTA PAUL CAPSIS TAMSIN CARROLL STARRING IN MEDIA KIT www.rockyhorror.com.au PRESSMEDIA RELEASE RELEASE RICHARD O’BRIEN’S THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE ROCK’N’ROLL MUSICAL DON’T DREAM IT … SEE IT THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE ROCK‘N’ROLL MUSICAL OPENS IN FEBRUARY WITH A BRAND SPANKING NEW PRODUCTION. It’s astounding, time is fleeting and The Rocky Horror Show is back. We’re starting another sensation and we’re definitely not under sedation! A new Australian production of the much-loved Rocky Horror Show will open Sydney’s brand new Star Theatre in February 2008 and tickets go on sale on Monday 27 August. Co-Producer Paul Dainty, Chairman of Dainty Consolidated Entertainment says: “It’s a thrill to be bringing The Rocky Horror Show to the Australian stage. It is a timeless piece of theatre that has spanned decades. I know Australian audiences – both new and old fans – will love this show which stars some of our finest talents.” “This fresh production is an exciting new take on the world’s favourite rock ‘n’ roll musical. It brings together the hottest cast I have seen for a long time” commented co-producer Howard Panter, Joint Chief Executive Officer and Creative Director of the UK’s Ambassador Theatre Group. The Rocky Horror Show is an institution and one of theatre’s most endearing and outrageously fun shows. Its well-known and much-loved storyline goes something like this: Squeaky-clean sweethearts Brad and Janet knock on the door of an eerie house to use the phone after their car breaks down in the rain on a dark and stormy night.