Learning from Communities' Involvement in the Management Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoo- a Case Study Based on the Johannesburgzoo

UNIVERSITI OF KWAZULU-NATAL UNDERSTANDINGTHE EDUCATIONAL AND ENTERTAINMENT OPPORTUNITIES OF THE 'MODERN' ZOO- A CASE STUDY BASED ON THE JOHANNESBURGZOO By jo-Anne Pillay 963090182 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINIS1RATION In the Graduate Schoolof Business Supervisor: Professor Rembrandt Klapper Academic Year2006 DEG..ARATION This research has not been previously accepted for any degree and is not being cur rently considered for any other degree at any other university. I declare that this Dissertation contains my own work except where specificallyac knowledged jo-Anne Pillay 963090182 S~'6~"""""""""""" Date ~.q9~I.o.ep '.. II ACXNOWLEDGEMENfS Upon completing my research I would like to express my sincere appreciation towards the following personsand institutions: • Mysupervisor, ProfessorRembrandt Klopper • Christel Haddon • Isabella Kerrin • JenniferGray • Senzo Ncgobo • TheJohannesburg Zoo • Colleagues from Neo Solutions (PtJ? Ltd • Colleagues from the GtyofJohannesburg • And the participants in the interview process. To my family and friends for their constant SUPPOlt, understanding and encou ragement. To Raj Ramlaul for holdingmyhand throughthe fires. To my mother, Bernadette Pillay, whose undying love and support has helped me in everyfacet of my life. Thank you for instilling the love of the quest for know ledge in me. This dissertation was writtenin memoryof myfather, JustinMalcolm Pillayand mygrandparents Charles and RubyPillay. m ABSlRACf The management of the Johannesburg Zoo is currently attempting to 'turnaround' the entity. Being a part of the team that assisted the Johannesburg Zoo to formulate its business plan in 2004, the researcher developed an affiliationto the zoo and was moti vated to assist management with their efforts by conducting this study. -

Thanks to All Our Wonderful CANSA Supporters!!

APRIL 2007 Thanks to all our wonderful CANSA supporters!! A wonderful breakfast was held at Moyo’s at Zoo Lake on Tuesday We also received a wheelchair from Mr & Mrs Lombard after Mrs 27th March.Approximately 116 Joburg businesswomen attended Richards’ Cuppa. (and a few brave men too!) It was the first fundraiser, which will Sanlam Golf become an annual event and offered a mix of good food, good South Africa’s biggest amateur golf competition has been launched music and good company. was the main sponsor and launched IBM and will be held at golf clubs around the country.We will have their programme to assist with cancer research worldwide (see our CANSA representatives at each competition and we are looking for article “Help Defeat Cancer”). volunteers to help us as some of the clubs hold competitions on the Guests were treated to a sumptuous buffet breakfast while listen- same day. ing to the voice and guitar of Velaphi. Saxonwold’s day care patients Please contact Joanne Steytler on 011 646 5628 if you would like also joined in and the morning was rounded off by a colourful to assist. accapelo group. Due to popular demand, we will be hosting another function towards the end of the year – so please spread the word! Help needed Cresta Centre raised an amazing R135 000 with the Shavathon. Our Keurboom Interim Home is looking for help to start various projects such as Gardening, Baking, Sewing, Knitting,etc.The proj- We had lots of fun at Redhill School where R12 000 was raised ects aim to teach skills to patients during their stay at the Home, to spraying and cutting hair! raise funds and promote healthy lifestyles through activities. -

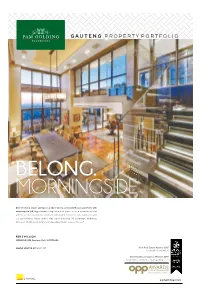

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Corner Oxford Road)

Saxonwold Prime Corner Stand on Oxford Road Johannesburg Major development potential 37 Englewold Drive (Corner Oxford Road) Tuesday, 14 July 2020 @ 12h00 Online Webcast Auction Luke Rebelo | 072 493 2148 | [email protected] Version 1: 24 June 2020 NT Prime Corner Stand on Oxford Road Saxonwold, Johannesburg Index Disclaimer, Auction Information and Terms & Conditions Page 3 Property Images Page 4 Executive Summary & Key Investment Highlights Page 6 General Information Page 7 Locality Information Page 8 Property Description Page 10 Floor Layout Plans Page 13 Projected Gross Annual Income – Summary Page 15 Projected Gross Annual Income - Detailed Page 16 Lease Summaries Page 17 Rates Statement Page 19 General Plan Diagram Page 21 /AucorProperty www.aucorproperty.co.za 2 Prime Corner Stand on Oxford Road Saxonwold, Johannesburg Disclaimer, Auction Information and Terms & Conditions Disclaimer Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither Aucor Corporate (Pty) Ltd T/A Aucor Property nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to negligence or otherwise of Aucor Corporate (Pty) Ltd T/A Aucor Property or the Seller/s or any other person. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Auction Information Deposit 5% of the bid price Commission 10% plus 15% VAT thereon of the bid price Confirmation period 2 Business days Rules of auction and conditions of sale are available at www.aucorproperty.co.za/ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Terms & Conditions R50 000 refundable deposit (strictly bank guaranteed cheque or cash transfer only). -

Provincial Gazette Extraordinary Buitengewone Provinsiale Koerant

~:.. , , ' , , , .. , " ,,' " .... ' .. - ,,-_... .... - ,,-_....._.- ~It:: _- • ~ "LI VI IV ~ It:: Ic.lr- a.J I C. ~" LI VI IV ~ I t: ,........ ..- ,..... ... ..- __ __ ~_1c.I I It:: IVL::lI ~_1c.I I C. IVL::lI , , " -, ..... Provincial Gazette Extraordinary Buitengewone Provinsiale Koerant .. " OCTOBER Vol. 17 PRETORIA, 24 OKTOBER 2011 No. 247 2 No.247 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 24 OCTOBER 2011 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an "OK" slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender's respon sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS • INHOUD Page Gazette No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES 2832 National Heritage Resources Act (25/1999): Provincial Heritage Resources Authority Gauteng: Provisional protection: Magaliesberg Station Masters House, Magaliesberg . 3 247 2833 do.: do.: Formal protection: Chancellor House, Ferreirasdorp . 3 247 2834 do.: do.: Provisional protection: The Tom Jenkins Drive, Rietondale . 3 247 2835 do.: do.: do.: Winchester House, Houghton Estate . 4 247 2837 National Heritage Resources Act (25/1999): Provincial Heritage Resources Authority Gauteng: Provisional protection: Patel House, Surtee's Building, Pageview . 4 247 2838 do.: do.: do.: House Ghyoot, Waterkloof Ridge . -

Region B Contact & Information Directory

REGION B CONTACT & INFORMATION DIRECTORY UPDATED JANUARY 2016 REGION B CONTACT & INFORMATION DIRECTORY: JANUARY 2016 INDEX NAME PAGE Emergency Numbers …………………………………………………………………… 1 Head Office Staff A – Z …………………………………………………………………… 1 – 6 Ward Councillors …………………………………………………………….…….. 6 -7 Ward Governance Administrators …………………………………………………………………… 8 PR Councillors …………………………………………………………………… 8 Group Citizen Relationship & Urban Management (CRUM): Head Office …………………………… 8 - 9 Regional Directors A – G …………………………………………………………... 9 - 10 Citizen Relationship & Urban Management Management Support …………………………………………………… 10 Area Based Management …………………………………………………… 11 Citizen Relationship Management …………………………………………………... 11 Integrated Service Delivery …………………………………………………... 12 Planning, Profiling & Data Management …..……………………………………… 12 Health Community Health Clinics …………………………………………………… 13 – 14 Environmental Health …………………………………………………… 15 – 18 Housing …………………………………………………………………… 19 Libraries …………………………………………………………………… 20-21 Social Development TDC (Transformation & Development Centre) ………………………………………… 22 Techno Centre …………………………………………………………………… 23 Sport and Recreation Recreation …………………………………………………………………… 23 Recreation Centres …………………………………………………………………… 24 NAME PAGE Sport …………………………………………………………………… 25 Sports Clubs & Stadiums …………………………………………………………………… 25 – 26 Aquatics …………………………………………………………………… 26 Swimming Pools …………………………………………………………………… 26 – 27 Group Finance Revenue Shared Services Centre ………………………………………………….. 27 Development Planning Building Control -

Saxonwold, Randburg, Gauteng OFFERS from R8,750,000.00 25 Methwold Road

Executive Home FOR SALE Saxonwold, Randburg, Gauteng OFFERS FROM R8,750,000.00 25 Methwold Road Rudi 082 695 6658 Online @ www.sagrouponline.co.za By appointment only https://www.sagrouponline.co.za/Property/1234/executive-home- in-saxonwold 1. Property Address, Accounts & General Information 3 2. Description of Improvements 4 3. Property Photos 5 - 7 1. PROPERTY ADDRESS, ACCOUNTS & GENERAL INFORMATION Property Address: 25 Methwold road, Saxonwold, Johannesburg Property Type: Residential Erf number & Portion: ERF 353 Suburb & City: Saxonwold, Johannesburg Deeds Office: Johannesburg Title Deed No: T5308/931 Property Size: 2024 m² Zoning: Residential Monthly Rates & Taxes: ± R 5 282.01 per month Monthly Electricity: ± R 5 316.73 per month Monthly Water: ± R 1 922.87 per month Monthly Refuse: ± R 423.20 per month 2. DESCRIPTION OF IMPROVEMENTS • This 4 bedroom, 3 bathroom executive home has an understated elegance that will appeal to the discerning buyer. The large double doors at the entrance leads into a generous foyer, with a solid wood staircase to the upper level. The generous use of wood throughout, adds warmth and a sense of luxury. All fixtures and finishes complement this theme of understated luxury and elegance. • The kitchen is generous in size, affording space for family meals or a glass of wine with friends around the kitchen table and fireplace • The under roof outside entertainment area makes this home an absolute haven for the family who loves to entertain. The property has an outside studio that can be used for guests, as an art studio or home office • The established lush garden with a pool has large trees with ample space without being too much to maintain. -

THE ORDER of APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa

THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg By Mpho Matsipa A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Nezar Alsayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Ananya Roy Spring 2014 THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements ii List of Illustrations iii List of Abbreviations vi EAVESDROPPING 1 0.1 Regimes of Representation 6 0.2 Theorizing Globalization in Johannesburg 9 0.2.1 Neo‐liberal Urbanisms 10 0.2.2 Aesthetics and Subject Formation 12 0.2.3 Race Gender and Representation 13 0.3 A note on Methodology 14 0.4 Organization of the Text 15 1 EXCAVATING AT THE MARGINS 17 1.1 Barbaric Lands 18 1.1.1 Segregation: 1910 – 1948 23 1.1.2 Grand Apartheid: 1948 – 1960s 26 1.1.3 Late Apartheid: 1973 – 1990s 28 1.1.4 Post ‐ Apartheid: 1994 – 2010 30 1.2 Locating Black Women in Johannesburg 31 1.2.1 Excavations 36 2 THE LANDSCAPE OF PUBLIC ART IN JOHANNESBURG 39 2.1 Unmapping the City 43 2.1.1 The Dying Days of Apartheid: 1970‐ 1994 43 2.1.2 The Fiscal Abyss 45 2.2 Pioneers of the Cultural Arc 49 2.2.1 City Visions 49 2.2.2 Birth of the World Class African City 54 2.2.3 The Johannesburg Development Agency 58 2.3 Radical Fragments 61 2.3.1 The Johannesburg Art in Public Places Policy 63 3 THE CITY AS A WORK OF ART 69 3.1 Long Live the Dead Queen 72 3.1.2 Dereliction Can be Beautiful 75 3.1.2 Johannesburg Art City 79 3.2 Frontiers 84 3.2.1 The Central Johannesburg Partnership 19992 – 2010 85 3.2.2 City Improvement Districts and the Urban Enclave 87 3.3 Enframing the City 92 3.3.1 Black Woman as Trope 94 3.3.2 Branding, Art and Real Estate Values 98 4 DISPLACEMENT 102 4.1 Woza Sweet‐heart 104 4.1.1. -

04Notice of Opposition.Pdf

IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA CASE NO: CCT 135 / 2012 In the matter between: MEMBER OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL FOR First Applicant EDUCATION IN GAUTENG PROVINCE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: GAUTENG Second Applicant DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISTRICT DIRECTOR JOHANNESBURG EAST Third Applicant D9: GAUTENG DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION and THE GOVERNING BODY OF RIVONIA First Respondent PRIMARY SCHOOL RIVONIA PRIMARY SCHOOL Second Respondent CELE, STHABILE Third Respondent MACKENZIE, AUBREY Fourth Respondent DRYSDALE, CAROL Fifth Respondent NOTICE OF OPPOSITION S I R S PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that the abovementioned First and Second Respondents hereby give notice of their intention to oppose the application for leave to appeal, on the grounds set out in the Answering Affidavit, and appoint the address of their attorneys as set out hereunder as the address at which they will accept service of all processes and documents in this matter. Page 2 DATED at SANDTON this day of JANUARY 2013 _____________________________________ FIRST AND SECOND RESPONDENTS' ATTORNEYS SHEPSTONE & WYLIE Ground Floor, The Lodge 38 Wierda Road West, Wierda Valley Sandton, Johannesburg PO Box 2862 Saxonwold 2132 Docex 12 Rosebank Tel: 011 290 2540 Fax: 0866 734 362 Email: [email protected] (Ref: KJR/RIVO22729.2) To: THE REGISTRAR OF THE ABOVE HONOURABLE COURT JOHANNESBURG And to: STATE ATTORNEY Attorneys for 1st - 3rd Applicants 10th Floor North State Building 95 Market Street (Cnr. Kruis Street) JOHANNESBURG Docex 688 Johannesburg Tel: 011 330 7600 Fax: 011 337 7180 Ref: R -

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region E

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION E No. Councillors Party: Region: Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & No: Contact Details: 1. Cllr. Bongani Nkomo DA E 32 Limbro Park, Modderfontein, Katlego More 011 582 -1606/1589 Greenstone, Longmeadow, 083 445 1468 073 552 0680 Juskei View, Buccleuch, [email protected] Sebenza, Klipfontein 2. Cllr. Lionel Mervin Greenberg DA E 72 Dunhill, Fairmount ,Fairmount Mpho Sepeng 082 491 6070 Ridge EXT 1,2 Fairvale, 011 582 1585 [email protected] Fairvale EXT 1, Glenkay, 082 418 5145 Glensan, Linksfield EXTs 1, 2, [email protected] 3, 4, 5, Linksfield North, Linksfield Ridge EXT 1, Sandringham, Silvamonte EXT1,Talbolton, Sunningdale, Sunningdale Ext 1,2,3,4,5, 7,8,11,12,Sunningdale Percelia, Percelia Estate, Percelia Ext, Sydenham, Glenhazel, and Orange Grove North of 14th Street,Viewcrest 3. Cllr. Eleanor Huggett DA E 73 Bellevue, Fellside, Houghton Teboho Maapea 071 785 8068 Estate, Mountain View, 079 196 5019 [email protected] Norwood, Oaklands, Orchards, [email protected] Parkwood EXT1, Riviera, Saxonwold EXTs1, 2,3,4, Victoria EXT2 Killarney 4. Cllr. David Ross Fisher DA E 74 Wanderers, Waverley, Mpho Sepeng 011 582-1609 Bagleyston, Birdhaven, Birnam, 011 582 1585 082 822 6070 Bramley Gardens, Cheltondale, 082 418 5145 [email protected] Chetondale EXT1, 2, 3, Elton [email protected] Hill EXTs 1, 2, 3, 4, Fairway, Fairwood, Forbesdale, Green World,Glenhazel EXTs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14 Gresswold, Hawkins Estate, Hawkins Estate EXT1, Highlands North EXT2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, Highlands North Extension,Illovo EXT 1,Kentview,Kew,Maryvale, Melrose,Melrose Estate,Melrose Ext 1,2, Melrose North Ext 1,2,3,4,57,8,Orange Grove,Orchards From Hamlen to African Street(Highroad border), 1,2,Raedene Estate, Raedene Estate Ext 1,Raumarais Park ,Rouxville, Savoy Estate, Ridge, 5. -

The Johannesburg Zoo 2009/10

THE JOHANNESBURG ZOO (An association incorporated under Section 21) Registration No: 2000/022951/08 November 2010 (In terms of Section 121 of the Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003 and Section 46 of the Municipal Systems Act, 2000) THE JOHANNESBURG ZOO ASSOCIATION INCORPORATED UNDER SECTION 21 OF THE COMPANIES ACT COMPANY INFORMATION: Registration number: 2000/022951/08 Registered Address: Jan Smuts Avenue Parkview 2122 Postal Address: Private Bag X13 Parkview 2122 Telephone number : (011) 646 2000 Fax number : (011) 646 4782 Website : www.jhbzoo.org.za Bankers : ABSA Bank of SA Limited Auditors : Auditor-General of South Africa 2 SECTION 1: PROFILE Scope of the Report/Company Profile/Vision, values and strategic objectives SECTION 2: LEADERSHIP PROFILE Member of the Mayoral Committee‟s Review Chairperson‟s Review Chief Executive Officer‟s Review Chief Financial Officer‟s Review Board of Directors SECTION 3: PERFORMANCE REVIEW Highlights and Achievements Performance against IDP and City Scorecard Assessment of arrears on service charges Statement of amounts owed by Government Departments and Public Entities Recommendations and Plans for the next financial year. SECTION 4: CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Introduction Statement of Compliance Code of Ethics Breach of Governance Procedures Conflicts of Interest Governance Structure - Board of Directors - Board Composition - Board Induction and information - Board leadership - Board evaluation - Remuneration - Schedule of attendance at meetings 3 Board Committees - Introduction - Functions and mandate - Key Activities - Members CHAPTER 5: SUSTAINABILITY REPORT CHAPTER 6: FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 4 SCOPE OF THE REPORT This annual report covers the entity‟s governance, financial, social responsibility, environmental, broader economic and overall sustainability performance for the 2009/2010 year.