Water Conservation & Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bargarh District

Orissa Review (Census Special) BARGARH DISTRICT Bargarh is a district on the Western border of The district of Bargarh is one of the newly Orissa. Prior to 1992, it was a subdivision of created districts carved out of the old Sambalpur Sambalpur district. Bargarh has been named after district. It has a population of 13.5 lakh of which the headquarters town Bargarh situated on the 50.62 percent are males and 49.38 percent left bank of the Jira river. The town is on the females. The area of the district is 5837 sq. Km National Highway No.6 and located at 59 km to and thus density is 231 per sq.km. The population the west of Sambalpur district. It is also served growth is 1.15 annually averaged over the decade by the D.B.K railway running from Jharsuguda of 1991-2001. Urban population of the district to Titlagarh. The railway station is about 3 kms constitute 7.69 percent of total population. The off the town. A meter gauge railway line connects Scheduled Caste population is 19.37 percent of Bargarh with the limestone quarry at Dunguri. The total population and major caste group are Ganda main Hirakud canal passes through the town and (54.82), Dewar (17.08) and Dhoba etc. (6.43 is known as the Bargarh canal. percent) among the Scheduled Castes. Similarly The District of Bargarh lies between the Scheduled Tribe population is 19.36 percent 200 45’ N to 210 45’N latitude and 820 40’E to of total and major Tribes groups of the total Tribes 830 50’E longitude. -

Bargarh District, Odisha

MIGRATION STUDY REPORT OF 1 GAISILAT BLOCK OF BARGARH DISTRICT OF ODISHA PREPARED BY DEBADATTA CLUB, BARGARH, ODISHA SUPPORTED BY SDTT, MUMBAI The Migration Study report of Gaisilat block of Bargarh district 2 Bargarh district is located in the western part of the state of Odisha come under Hirakud command area. The district continues to depict a picture of chronic under development. The tribal and scheduled caste population remains disadvantaged social group in the district, In this district Gaisilat Block Map absolute poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition are fundamental form of deprivation in which seasonal migration of laborers takes place. About 69.9 percent of the rural families in Bargarh are below the poverty line; of this 41.13 percent are marginal farmers, 22.68 percent small farmers and 25.44 percent agricultural laborers. Bargarh district of Odisha is prone to frequent droughts which accentuate the poverty of the masses and forces the poor for migration. In our survey area in 19 Grampanchyats of Gaisilat Block of Bargarh District where DEBADATTA CLUB (DC) has been undertaken the survey and observed that in many villages of these western Orissa districts almost half of the families migrate out bag and baggage during drought years. Only old and infirm people under compulsion live in the village. All able-bodied males and females including small children move out to eke out their living either as contract workers in the brick kiln units or as independent wage workers/self-employed workers of the urban informal sector economy in relatively developed regions of the state and outside the state. -

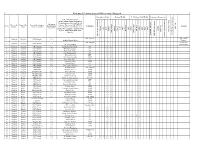

Defaulter-Private-Itis.Pdf

PRIVATE DEFAULTER ITI LIST FOR FORM FILL-UP OF AITT NOVEMBER 2020 Sl. No. District ITI_Code ITI_Name 1 ANGUL PR21000166 PR21000166-Shivashakti ITC, AT Bikash Nagar Tarang, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 2 ANGUL PR21000192 PR21000192-Diamond ITC, At/PO Rantalei, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 3 ANGUL PR21000209 PR21000209-Biswanath ITC, At-PO Budhapanka Via-Banarpal, Anugul, Odisha, - 759128 4 ANGUL PR21000213 PR21000213-Ashirwad ITC, AT/PO Mahidharpur, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 5 ANGUL PR21000218 PR21000218-Gayatri ITC, AT-Laxmi Bajar P.O Vikrampur F.C.I, Anugul, Odisha, - 759100 6 ANGUL PR21000223 PR21000223-Narayana Institute of Industrial Technology ITC, AT/PO Kishor, Anugul, Odisha, -759126 7 ANGUL PR21000231 PR21000231-Orissa ITC, AT/PO Panchamahala, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 8 ANGUL PR21000235 PR21000235-Guru ITC, At.Similipada, P.O Angul, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 9 ANGUL PR21000358 PR21000358-Malayagiri Industrial Training Centre, Batisuand Nuasahi Pallahara, Anugul, Odisha, -759119 10 ANGUL PR21000400 PR21000400-Swami Nigamananda Industrial Training Centre, At- Kendupalli, Po- Nukhapada, Ps- Narasinghpur, Cuttack, Odisha, -754032 11 ANGUL PR21000422 PR21000422-Matrushakti Industrial Training Institute, At/po-Samal Barrage Town ship, Anugul, Odisha, -759037 12 ANGUL PR21000501 PR21000501-Sivananda (Private) Industrial Training Institute, At/Po-Ananda Bazar,Talcher Thermal, Anugul, Odisha, - 13 ANGUL PU21000453 PU21000453-O P Jindal Institute of Technology & Skills, Angul, Opposite of Circuit House, Po/Ps/Dist-Angul, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 14 BALASORE -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

Health Centers

LIST OF HEALTH CENTERS OF NUAPADA DISTRICT SL.No Name of the Block Name of the CHC Name of the Sector Name of the SC Name of the PHC(N) 1 Beltukuri PHC(N), BELTUKRI 2 Beltukri Bisora 3 Bhaleswar 4 Biromal PHC(N), BIROMAL 5 Jampani Biromal 6 Kuliabandha 7 Kodomeri 8 Darlimunda PHC(N) ,DARLIMUNDA 9 Saipala 10 Maulibhata Darlimunda 11 Tanwat 12 Godfula NUAPADA CHC, KHARIAR ROAD 13 Kotenchuan 14 Dharambandha PHC(N),DHARAMBANDHA 15 Motanuapada 16 Kendubahara Dharambandha 17 Amanara 18 Sarabong 19 Maraguda 20 Parkod CHC Khariar road 21 Jenjera 22 Khariar road Amsena 23 Gotma 24 Khariar Road 25 Tarbod PHC(N), TARBOD 26 Jatgarh 27 Darlipada 28 Turbod Siallati 29 Kurumpuri 30 Samarsingh 31 Lakhna 32 Budhikomna PHC(N), BUDHHIKOMNA Budhikomna CHC,KOMNA & CHC , KOMNA BHELLA 33 Kandetara 34 Budhikomna Nuagaon 35 Gandamer PHC(N) ,DARLIPADA CHC,KOMNA & CHC , 36 KOMNA Suklimundi BHELLA 37 Bhella PHC(N),SUNABEDA 38 Agren 39 Rajna Bhela 40 Chhata 41 Bisibahal 42 Sunabeda 43 Konabira 44 Pendrawan 45 Komna Tikrapada 46 Udyanbandh 47 Komna 48 Duajhar PHC(N),DUAJHAR 49 Kotamal 50 Nehena 51 DUAJHAR Kirkita 52 Dhanksar 53 Birighat 54 Lanji PHC(N), TUKLA 55 Bargaon 56 Khudpej KHARIAR CHC,KHARIAR 57 Bargaon Badmaheswar 58 Bhojpur PHC(N), LANJI 59 Bhuliasikuan 60 Amlapali 61 Lachhipur 62 Badi Khariar 63 Khasbahal 64 Khariar 65 Tukla 66 Sinapali PHC(N) ,LIAD Sinapali SINAPALI CHC,SINAPALI 67 Bramhaniguda 68 Bargaon Sinapali 69 Gandabahali 70 Godal 71 Singhjhar 72 Hatibandha PHC(N),HATIBANDHA 73 Chalna Hatibandha 74 Bharuamunda 75 SINAPALI CHC,SINAPALI Makhapadar 76 Timanpur PHC(N), TIMANPUR 77 Timnapur Niljee 78 Gorla 79 Kendumunda 80 Badibahal Kendumunda 81 Kuliadunguri 82 Nagalbod 83 Boden Bhainsadani PHC(N) Bhainsadani 84 Boden 85 BODEN Boirgaon 86 BODEN Damjhar PHC(N),DAMJHAR 87 BODEN Nagpada 88 BODEN Sunapur 89 BODEN Karlakot 90 BODEN Khaira 91 BODEN Karangamal Karngamal PHC(N), KARANGAMAL CHC,BODEN 92 BODEN Kulekela 93 BODEN Farsara 94 BODEN Larka 95 BODEN Litisargi 96 BODEN Rokal 97 BODEN 98 BODEN. -

Namebased Training Status of DP Personnel

Namebased Training status of DP Personnel - Nayagarh Reproductive Health Maternal Health Neo Natal and Child Health Programme Management Name of Health Personnel (ADMO, All Spl., MBBS, AYUSH MO, Central Drugstore MO, Lab Tech.- all Category of Name of the Name of the Name of the institution Category, Pharmacist, SNs, LHV, H.S Sl. No. the institutions Designation Remarks District. Block (Mention only DPs) (M)), ANM, Adl. ANM, HW(M), Cold (L1, L2, L3) Chain Tech. Attendant- OT, Labor Room Trg IMEP BSU NSV NRC MTP IYCF LSAS IUCD NSSK FBNC EmOC DPHM IMNCI Minilap BEmOC RTI/STI PPIUCD & OPD. DPMU Staff, BPMU Staff, FIMNCI Induction Induction training PMSU Trg. PMSU IMNCI (FUS) IMNCI Sweeper (21SAB days) Fin. Mgt Trg. (Accounts trg) PGDPHM (Full Time) PGDPHSM (E-learning) Laparoscopic sterilization 1 atMDP reputed institution Asst. Surgeon 1 1 1 1 PG At SCB 1 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Dr Bijay Kumar Meher Cuttack Asst. Surgeon 1 1 Transfert to 2 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Dr Prasanta Dash Nabarangapur 3 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Smt.Sudiptarani Nanda SN 1 1 1 1 4 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Miss Sabita Kunar SN 1 1 1 1 5 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Miss Sabitri Dash SN 1 1 1 1 6 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Mrs. Rasmirani Lal SN 1 1 1 1 7 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Mrs Kabita Jena LHV 1 1 1 1 8 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Mrs.Jayanti Samartha ANM 1 1 1 1 9 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Swarnalata Joshi SN 1 10 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Taposwani Panda ANM 1 1 11 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Nibedita Baral SN 12 Nuapada Sinapali CHC Sinapali L2 Jyoti Manjari Baitharu SN 13 Nuapada Sinapali Liad PHC(N) L1 Dr Dipdil Sahoo Asst. -

The Cultural Politics of Textile Craft Revivals

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2012 The Cultural Politics of Textile Craft Revivals Suzanne MacAulay University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, [email protected] Jillian Gryzlak School of the Art Institute of Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf MacAulay, Suzanne and Gryzlak, Jillian, "The Cultural Politics of Textile Craft Revivals" (2012). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 712. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/712 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Cultural Politics of Textile Craft Revivals Suzanne MacAulay [email protected] & Jillian Gryzlak [email protected] To all the fine-spirited and creative women, who were mentors and guides in the most profound sense and have since died. Our joint paper critiques and appraises the cultural politics of textile revitalization projects. The format follows a conversational style as we exchange thoughts about our very different experiences as a folklorist doing fieldwork in Colorado’s San Luis Valley and as a weaver and participant observer involved in a weaving workshop located in the Bargarh district of Orissa, India. One of our chief mutual interests, conditioned by the assumption that “all tradition is change,” analyzes the political bases for craft-inspired workshops that attempt to revive traditional arts as economic redevelopment projects. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

Inner Front.Pmd

BUREAU’S HIGHER SECONDARY (+2) GEOLOGY (PART-II) (Approved by The Council of Higher Secondary Education, Odisha, Bhubaneswar) BOARD OF WRITERS (SECOND EDITION) Dr. Ghanashyam Lenka Dr. Shreerup Goswami Prof. of Geology (Retd.) Professor of Geology Khallikote Autonomous College, Berhampur Sambalpur University, Jyoti Vihar, Burla Dr. Hrushikesh Sahoo Dr. Sudhir Kumar Dash Emeritus Professor of Geology Reader in Geology Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Sundargarh Autonomous College, Sundargarh Dr. Rabindra Nath Hota Dr. Nabakishore Sahoo Professor of Geology Reader in Geology Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Khallikote Autonomous College, Berhampur Dr. Manoj Kumar Pattanaik Lecturer in Geology Khallikote Autonomous College, Berhampur BOARD OF WRITERS (FIRST EDITION) Dr. Satyananda Acharya Mr. Premananda Ray Prof. of Geology (Retd.) Reader in Geology (Retd.) Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Mr. Anil Kumar Paul Dr. Hrushikesh Sahoo Reader in Geology (Retd.) Professor of Geology Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Dr. Rabindra Nath Hota Reader in Geology, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar REVIEWER Dr. Satyananda Acharya Professor of Geology (Retd) Former Vice Chancellor of Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Published by THE ODISHA STATE BUREAU OF TEXTBOOK PREPARATION AND PRODUCTION Pustak Bhawan, Bhubaneswar Published by: The Odisha State Bureau of Textbook Preparation and Production, Pustak Bhavan, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India First Edition - 2011 / 1000 Copies Second Edition - 2017 / 2000 Copies Publication No. - 194 ISBN - 978-81-8005-382-5 @ All rights reserved by the Odisha State Bureau of Textbook Preparation and Production, Pustak Bhavan, Bhubaneswar, Odisha. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission from the Publisher. -

Socio-Economic Profile of Handloom Weaving Community: a Case Study of Bargarh District, Odisha

Socio-Economic Profile of Handloom Weaving Community: A Case Study of Bargarh District, Odisha A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela In partial fulfilment of the requirement of the award of the Degree of Master of Arts in Development Studies Submitted by SANDHYA RANI DAS Roll No. - 413HS1006 Under the Supervision of Dr. Bikash Ranjan Mishra Department of Humanities and Social Sciences NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, ROURKELA SUNDARGARH - 769008, ODISHA, INDIA MAY 2015 I DECLARATION I, hereby declare that my final year project on “Socio-Economic profile of Handloom weaving community: A case study of Bargarh District, Odisha" at National Institute of Technology Rourkela, Odisha in the academic year 2014-15 is submitted under the supervision of Dr. Bikash Ranjan Mishra. The information submitted here is true and original to the best of my knowledge. Sandhya Rani Das R. N. 413HS1006 MA in Development Studies Department of Humanities and Social Sciences National Institute of Technology, Rourkela II Dr. Bikash Ranjan Mishra Date: Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Rourkela National Institute of Technology Rourkela- 769008 Odisha, India CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled, “Socio- Economic Profile of Handloom weaving community: A Case study of the Bargarh District, Odisha” submitted by Sandhya Rani Das in partial fulfilment of requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Development Studies of the department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, Odisha, is carried out by her under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge the subject embodied in the dissertation has not been submitted to any other University for the award of any degree. -

Prevalence of and Factors Contributing to Anxiety, Depression and Cognitive

Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 80 (2019) 38–45 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/archger Prevalence of and factors contributing to anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders among urban elderly in Odisha – A study through the health T systems’ Lens ⁎ Sudharani Nayaka, Mrinal Kar Mohapatrab, Bhuputra Pandab, a Government of Odisha, Health and Family Welfare Department, Nilakantha Nagar, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, 751012, India b PHFI, Indian Institute of Public Health, Plot No. 267/3408, Jayadev Vihar, Mayfair Lagoon Road, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, 751013, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: Growing geriatric mental health needs of urban population in India pose several programmatic Anxiety challenges. This study aimed to assess anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders among urban elderly, and Depression explore availability of social support mechanisms and of a responsive health system to implement the national Cognitive disorders mental health programme. Elderly Methods: 244 respondents were randomly selected from Berhampur city. We administered a semi-structured Odisha interview schedule to assess substance abuse, chronic morbidity, anxiety, depression and cognitive abilities. Health systems Further, in-depth interviews were conducted with 25 key informants including district officials, psychiatrists, and programme managers. We used R software and ‘thematic framework’ approach, respectively, for quanti- tative and qualitative