UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression

1 Carmichael, J.V. (2014). Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression. In M. Alfino & L. Koltutsky (Eds.), The Library Juice Press Handbook of Intellectual Freedom: Concepts, Cases and Theories (pp.380-404). Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press. Made available courtesy of Litwin Books, LLC: http://libraryjuicepress.com/IF- handbook.php ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Litwin Books, LLC. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression Coming from the insularity and prejudices of England [. .] she [Madge Garland] also found something as elusive and enduring as this aesthetic awakening: an instinct for the possibilities of friendship and an understanding of the world as her home. She called it “freedom of thought.” Lisa Cohen, For All We Know (2012) Introduction Our ability to use words as we see fit is perhaps the primary measure of our intellectual freedom. Otherwise, we would live in a dream world, largely unexpressed. We form hierarchical classifications of value, create laws by which we function as societies, interpret law and custom, and make decisions that in turn are justified by ethical and moral understandings through words. This essay discusses words and their changing meanings over time as they have referred to sexual orientation and gender expression, and how language generally engages intellectual freedom. How humans have designated meaning by symbols and signs is one of the enduring objects of study. Words conceal as well as reveal meaning too. Minority members invent local patois understood only by initiates so that they may communicate with one another without being understood by members of the usually oppressive majority. -

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

![Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2283/barbara-gittings-and-kay-tobin-lahusen-collection-1950-2009-bulk-1964-1975-ms-coll-3-92283.webp)

Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3

Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3 Finding aid prepared by Alina Josan on 2015 PDF produced on July 17, 2019 John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives, William Way LGBT Community Center 1315 Spruce Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 [email protected] Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical ................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Subject files ................................................................................................................................................ -

Jun Jul. 1970, Vol. 14 No. 09-10

Published bi-monthly by the Daughters of ONCE MORE WITH FEELING Bilitis, Inc., a non-profit corporation, at THE I have discovered my most unpleasant task as editor . having to remind y. 'i P.O. Box 5025, Washington Station, now and again of your duty as concerned reader. Not just reader, concern« ' reader. Reno, Nevada 89503. UDDER VOLUME 14 No. 9 and 10 If you aren’t — you ought to be. JUNE/JULY, 1970 Those of you who have been around three or more years of our fifteen years n a t io n a l OFFICERS, DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS, INC know the strides DOB has made and the effort we are making to improve this magazine. To continue growing as an organization we need more women, women . Rita Laporte aware they are women as well as Lesbians. If you have shy friends who might be President . jess K. Lane interested in DOB but who are, for real or imagined reasons, afraid to join us — i t h e l a d d e r , a copy of WHAT i w r ■ ’ '^hich shows why NO U N t at any time in any way is ever jeopardized by belonging to DOB or by t h e LADDER STAFF subscribing to THE LADDER. You can send this to your friend(s) and thus, almost surely bring more people to help in the battle. Gene Damon Editor ....................... Lyn Collins, Kim Stabinski, And for you new people, our new subscribers and members in newly formed and Production Assistants King Kelly, Ann Brady forming chapters, have you a talent we can use in THE LADDER? We need Bobin and Dana Jordan wnters always in all areas, fiction, non-fiction, biography, poetry. -

The Year 1969 Marked a Major Turning Point in the Politics of Sexuality

The Gay Pride March, begun in 1970 as the In the fertile and tumultuous year that Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade to followed, groups such as the Gay commemorate the Stonewall Riots, became an Liberation Front (GLF), Gay Activists annual event, and LGBT Pride months are now celebrated around the world. The march, Alliance (GAA), and Radicalesbians Marsha P. Johnson handing out flyers in support of gay students at NYU, 1970. Photograph by Mattachine Society of New York. “Where Were Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. which demonstrates gays, You During the Christopher Street Riots,” The year 1969 marked 1969. Mattachine Society of New York Records. sent small groups of activists on road lesbians, and transgender people a major turning point trips to spread the word. Chapters sprang Gay Activists Alliance. “Lambda,” 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. Gay Liberation Front members marching as articulate constituencies, on Times Square, 1969. Photograph by up across the country, and members fought for civil rights in the politics of sexuality Mattachine Society of New York. Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. “Homosexuals Are Different,” 1960s. in their home communities. GAA became a major activist has become a living symbol of Mattachine Society of New York Records. in America. Same-sex relationships were discreetly force, and its SoHo community center, the Firehouse, the evolution of LGBT political tolerated in 19th-century America in the form of romantic Jim Owles. Draft of letter to Governor Nelson A. became a nexus for New York City gays and lesbians. Rockefeller, 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. friendships, but the 20th century brought increasing legal communities. -

OUT of the PAST Teachers’Guide

OUT OF THE PAST Teachers’Guide A publication of GLSEN, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network Page 1 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Why LGBT History? 2 Goals and Objectives 3 Why Out of the Past? 3 Using Out of the Past 4 Historical Segments of Out of the Past: Michael Wigglesworth 7 Sarah Orne Jewett 10 Henry Gerber 12 Bayard Rustin 15 Barbara Gittings 18 Kelli Peterson 21 OTP Glossary 24 Bibliography 25 Out of the Past Honors and Awards 26 ©1999 GLSEN Page 2 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Why LGBT History? It is commonly thought that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered (LGBT) history is only for LGBT people. This is a false assumption. In out current age of a continually expanding communication network, a given individual will inevitably e interacting with thousands of people, many of them of other nationalities, of other races, and many of them LGBT. Thus, it is crucial for all people to understand the past and possible contributions of all others. There is no room in our society for bigotry, for prejudiced views, or for the simple omission of any group from public knowledge. In acknowledging LGBT history, one teaches respect for all people, regardless of race, gender, nationality, or sexual orientation. By recognizing the accomplishments of LGBT people in our common history, we are also recognizing that LGBT history affects all of us. The people presented here are not amazing because they are LGBT, but because they accomplished great feats of intellect and action. These accomplishments are amplified when we consider the amount of energy these people were required to expend fighting for recognition in a society which refused to accept their contributions because of their sexuality, or fighting their own fear and self-condemnation, as in the case of Michael Wigglesworth and countless others. -

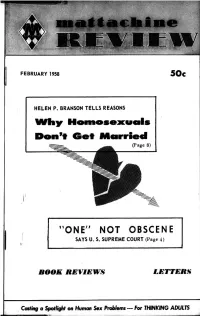

''One" Not Obscene Book Reviews Letters

FEBRUARY 1958 50c HELEN P. BRANSON TELLS REASONS Whx Homosexuals Don’t Get Married (Page 8) ’’ONE" NOT OBSCENE SAYS U. S. SUPREME COURT (Page 4) BOOK REVIEWS LETTERS Casting a Spotlight on Human Sox Problom s — For THINKING ADULTS ■ nattachf ne O ffici Of THf S04*D Of DI«ECrO*S inattachine ^rittg, M.. Copyright1 295S by the Matlacbine Society, incorporated FOURTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION-UATTACHIHE REVIEW founded January 1955 Mauaebint Foundation establisbid 1950; M<tttacbine*Society, Inc., ebartered 2954 OBSCENITY NEEDS TO BE DEFINED Volume IV FEBRUARY 1958 Number 2 The declaration by the U. S. Supreme Court that ONE magazine is not obscene (see page 4) is a victory for freedom of expression everywhere in the U. S., and not a gain for the 'homosexual press' Comtemt» alone. ARTICLES Changing times, changing attitudes and the general progress of human civilization call for old standards to be examined critically VICTORY FOR ONE by John Logan.........................................4 from time to time. The vague old bogey of obscenity is one of HOMOSEXUALS AS I SEE THEM by Helen P. Branson.. 8 these and within the past year or so sponsors of censorship on ob ENIGMA UNDER SCRUTING by Sexology Research Staff..14 scenity grounds have been called to task mote than once, but the right of Federal and State governments to judge and ban obscene SHORT FEATURES material has been upheld, as we believe it should be (see MATTA’ COURT RELEASES KINSEY MATERIAL..................................5 CHINE REVIEW. July 1957). We believe that ONE and MATTACHINE agree that freedom to CUSTOMS’ SEVEN-YEAR ITCH IS SCRATCHED............6 publish educational information, in an interesting and readable SOCIETY FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF SEX..........7 form, on the subject of sex variation is a genuine service in the ARMY REVIEWS RISK DISCHARGES.......................................14 interest of truth, justice and human well-being. -

Tavern Guild of San Francisco Records, 1961-1993

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt509nb9d7 No online items Guide to the Tavern Guild of San Francisco Records, 1961-1993 Processed by Martin Meeker and Heather Arnold. © 2003 The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. All rights reserved. Guide to the Tavern Guild of San 1995-02 1 Francisco Records, 1961-1993 Guide to the Tavern Guild of San Francisco Records, 1961-1993 Accession number: 1995-02 Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society San Francisco, California Processed by: Martin Meeker and Heather Arnold Date Completed: July, 2003 © 2003 The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Tavern Guild of San Francisco Records, Date (inclusive): 1961-1993 Accession number: 1995-02 Creator: Tavern Guild of San Francisco Extent: 21 boxes, 2 folders Repository: The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. San Francisco, California. Abstract: Minutes, correspondence, financial papers, membership materials, ephemera, photographs, and banners, 1962-1993 (11.25 linear feet), document the work of the Tavern Guild of San Francisco in promoting the interests of gay bars in San Francisco as well as the growth of the Tavern Guild into a well-known service and fundraising organization. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright to unpublished manuscript materials has been transferred to the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Tavern Guild of San Francisco Records, 1995-02, Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. Acquisition Information Donated to the GLBT Historical Society by Stanley Boyd in 1995. Organizational History The Tavern Guild of San Francisco (TGSF) was founded in 1962. -

Testing a Cultural Evolutionary Hypothesis,” Pg

ASEBL Journal – Volume 12 Issue 1, February 2016 February 2016 Volume 12, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature EDITOR St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ~ ▬ EDITORIAL BOARD [click on last name of lead/author to navigate to text] Divya Bhatnagar, Ph.D. ▬ Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. † Lesley Newson and Peter Richerson, “Moral Beliefs about Homosexuality: Kevin Brown, Ph.D. Testing a Cultural Evolutionary Hypothesis,” pg. 2 Alison Dell, Ph.D. Comments By: Robert A. Paul, pg. 21; Nicole A. Wedberg and Glenn Geher, pg. 23; Austin John Tom Dolack, Ph.D Jeffery and Todd Shackelford, pg. 24; Andreas De Block and Olivier Lemeire, pg. 27; James Waddington, pg. 29; Jennifer M. Lancaster, pg. 30 Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. Cheryl L. Jaworski, M.A. Newson’s and Richerson’s Reply to Comments, pg. 32 Joe Keener, Ph.D. ▬ † Craig T. Palmer and Amber L. Palmer, Eric Luttrell, Ph.D. “Why Traditional Ethical Codes Prescribing Self-Sacrifice Are a Puzzle to Evolutionary Theory: The Example of Besa,” pg. 40 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. Comments By: Eric Platt, Ph.D. David Sloan Wilson, pg. 50; Guilherme S. Lopes and Todd K. Shackelford, pg. 52; Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. Bernard Crespi, pg. 55; Christopher X J. Jensen, pg. 57; SungHun Kim, pg. 60 SCIENCE CONSULTANT Palmer’s And Palmer’s Reply to Comments, pg. 61 Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. ▬ EDITORIAL INTERN Lina Kasem † Aiman Reyaz and Priyanka Tripathi, “Fight with/for the Right: An Analysis of Power-politics in Arundhati Roy’s Walking with the Comrades,” pg. -

ONE Magazine and Its Readers

1 ONE Magazine and Its Readers he publication of ONE magazine’s first issue in January 1953 was a Twatershed moment in the history of American sexuality. Though not the first American publication to cater to homosexual readers (male phy- sique magazines had been coyly cultivating gay male readers for years), ONE was the first American publication openly and brazenly to declare itself a “homosexual magazine.” Many of its early readers doubted the magazine would last long. A reader, Ned, explained to ONE in a 1961 letter, “When the fifties were young I bought my first copies of ONE at a bookstore a few blocks from my studio on Telegraph Hill in San Francis- co. As I remember, those first copies were not very professional looking; and perhaps the contents were not impressive. But the mere fact that a bit of a magazine dared present the subject in writing by those who were [homosexual] was impressive. If anyone had predicted, however, that the mag. would live into the sixties, I’d have expressed doubts. One did look doubtful in those days.”1 ONE’s survival also seemed unlikely given the widespread antigay sentiment circulating throughout American society in the 1950s. Was ONE even legal? Could it be considered obscene for merely discussing homosexuality in affirmative tones? No one was sure in 1953. Yet ONE survived until 1967, by which time the country’s political, social, and cultural mood had shifted so dramatically that ONE seemed quaint and old-fashioned compared to the dozens of other gay publica- tions populating newsstands and bookstores. -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political -

Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement

The Hilltop Review Volume 7 Issue 2 Spring Article 17 April 2015 From “Black is Beautiful” to “Gay Power”: Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement Eric Denby Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Denby, Eric (2015) "From “Black is Beautiful” to “Gay Power”: Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement," The Hilltop Review: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview/vol7/iss2/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 132 From “Black is Beautiful” to “Gay Power”: Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement Runner-Up, 2014 Graduate Humanities Conference By Eric Denby Department of History [email protected] The 1960s and 1970s were a decade of turbulence, militancy, and unrest in America. The post-World War II boom in consumerism and consumption made way for a new post- materialist societal ethos, one that looked past the American dream of home ownership and material wealth. Many citizens were now concerned with social and economic equality, justice for all people of the world, and a restructuring of the capitalist system itself. According to Max Elbaum, the