The God of Every Day Wrath – Psalm 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 7 Worksheet

Introduction: The next group of psalms (7-14) deal with the same basic issue last the previous four: David’s distress/affliction at the hands of his enemies. Shiggaion? There are many terms used in the heading of the psalms that often refer the psalm to specific instruments or to the director of music. This term might fall somewhere in between. The Septuagint simply “translates” it into Greek with the word “psalm”, evidently pointing to the fact that already in antiquity the meaning of this word was lost. Psalm 7 1 O Lord my God, I take refuge in you; save and deliver me from all who pursue me, 2 or they will tear me like a lion and rip me to pieces with no one to rescue me. What gives this prayer a sense of urgency? Explain the significance of David calling the Lord “my” God. Unfortunately, we often can treat God like a last resort. How does the second line of verse two help us fight that temptation? 3 O Lord my God, if I have done this and there is guilt on my hands— 4 if I have done evil to him who is at peace with me or without cause have robbed my foe— 5 then let my enemy pursue and overtake me; let him trample my life to the ground and make me sleep in the dust. Compare David’s attitude toward the punishment any evil done by him deserves with your own attitude toward the same. What does the punishment David lists suggest about the nature of things he is accused of? Which is worse: to wrong a friend or to wrong an enemy? 6 Arise, O Lord, in your anger; rise up against the rage of my enemies. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms for the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms For the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel Today we start a new series in the Psalms. The Psalms provide a wonderful resource of Praying the Psalms inspiration and instruction for prayer and worship of God. Ezra collected the Psalms which were written over a millennium by a number of authors including David, Asaph, Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan and Moses. The Psalms are organized into 5 collections (1-41, 42-72, 73-89, 90-106, and 107-150). As we read the book of Psalms we see a variety of psalms including praise, lament, messianic, pilgrim, alphabetical, wisdom, and imprecatory prayers. The Psalms help us see the importance of God’s Word (Torah) and the hopeful expectation of God’s people for Messiah (Jesus). • Why is the “law of the Lord” such an important concept in Psalm 1 for bearing fruit as a follower of Jesus? • In John 15, Jesus says that apart from Him you can do nothing. Compare the message of Psalm 1 to Jesus’ words in John 15. Where are they similar? • Psalm 2 tells of kings who think they have influence and yet God laughs at them (v. 3). Why is it important that we seek our refuge in Jesus (2:12)? • Our heart for Bethel Church in this season is that we would saturate ourselves with God’s Word, specifically the book of Psalms. We’ve created a reading plan that allows you to read a Psalm a day or several Psalms per day as well as a Proverb. -

Psalm 7 (God of Justice)

Psalm 7 God of Justice Introduction: According to the heading, Psalm 7 is a hymn that David "sang to the Lord concerning the words of Cush." We have no record in the Bible about the specifics of this situation. But the psalm tells us that David prayed to God "save and deliver me from all who pursue me, or they will tear me like a lion and rip me to pieces" (Psalm 7:1-2).David wants God to intervene, and he needs his help immediately. Commentators speculate that perhaps Cush had made false accusations about David to King Saul, which led to one of Saul's many attempts to kill David. Or he may have been one of Saul's officers and was a leader of those who hunted David for long periods of time. Regardless, David is confident that he is innocent of any wrongdoing that would have justified such relentless and unfair treatment. He makes his case before the Judge of all the earth to act in accordance with his righteousness and stop this perversion of justice from continuing any longer: "O righteous God . bring to an end the violence of the wicked. God is a righteous judge, a God who expresses his wrath every day" (Psalm 7:9, 11). This Psalm presents us with a fact that we find over and over again in scripture and that is that God is not only a just God, but that he is the great and final judge of all mankind and all matters. “For I the Lord love justice; I hate robbery and wrong; I will faithfully give them their recompense.” -Isaiah 61 “Blessed is he whose help is the God of Jacob, whose hope is in the Lord his God, who made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, who keeps faith forever; who executes justice for the oppressed, who gives food to the hungry. -

Bible Reading

How can a young person stay A V O N D A L E B I B L E C H U R C H D, on the path of purity? By OCUSE RIST F RED living according to your CH CENTE BIBLE word. I seek you with all my r heart; do not let me stray gethe from your commands. I have To hidden your word in my heart that I might not sin Your word is a lamp against you. Praise be to you, unto my feet and a Lord teach me your light to my path decrees. With my lips I recount all the laws that -PSALM 119:105 come from your mouth. I E H T SEPTEMBER rejoice in following your N I WED 1 Psalm 136 statutes as one rejoices in THU 2 Psalms 137-138 R great riches. I meditate on E FRI 3 Psalm 129 M SAT 4 Psalm 140-141 your precepts and consider M U SUN 5 Psalm 142, 139 your ways. I delight in your S MON 6 Psalm 143 decrees; I will not neglect TUE 7 Psalm 144 your word. WED 8 Psalm 145 PSALM 119:9-16 THU 9 Psalm 146 FRI 10 Psalms 147-148 SAT 11 Psalms 149-150 SUMMER 2021 SUN 12 Joshua 1 Every word of God is flawless; JULY AUGU ST THU 1 Psalms 27-28 SUN 1 Psalms 81-82, 63 he is a shield to those who FRI 2 Psalms 29-30 MON 2 Psalms 83-84 take refuge in him. -

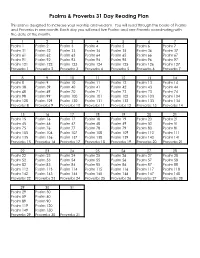

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

412 Reading Plan Psalms & Proverbs

412 Reading Plan Psalms & Proverbs Days 1-7 Day 1 Psalm 1 Are you blessed? How do you know? When facing this question, it’s easy to Psalm 16 respond by evaluating your circumstances to determine if you are blessed (a.k.a, “counting your blessings”). For example, you can consider the fact that you may have shelter, food, clothes, work, health, family, etc, and then arrive at the conclusion of “Yes, I am blessed.” However, this form of evaluating our status as “blessed” is far from what Scripture shows. In your reading of Psalm 1 today, we see that the one who is blessed is the one who has delight in the Lord. In other words, that person is experiencing and giving true value to the peace, presence, and power associated with being in a loving relationship with Jesus. As you read in Psalm 16, we have nothing good apart from God. So, rather than looking around to determine if and how you are blessed, the Lord invites us to look inside; to introspect and ask ourselves how we are growing in our relationship with God, for it is by that relationship alone that we find ourselves truly blessed. Day 2 Psalm 2 The Psalms are one of the five books of wisdom in the Bible. Full of poetry, Psalm 3 songs, and prayers, the Psalms contain the range of human emotions while Psalm 4 also foreshadowing and prophesying the future Messiah in Jesus. We see this clearly in Scripture like Psalm 2:6-7 through the challenges facing King David (2:2) and God’s decree over Jesus in His baptism (2:7). -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

A New English Translation of the Septuagint. 31 Psalms of Salomon

31-PsS-NETS-4.qxd 11/10/2009 10:39 PM Page 763 PSALMS OF SALOMON TO THE READER EDITION OF THE GREEK TEXT Since no critical edition of the Psalms of Salomon’s (PsSal) Greek text is available at the present time, the NETS translation is based on the edition of Alfred Rahlfs (Septuaginta. Id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interpretes, 2 vols. [Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt, 1935]). Rahlfs’s text is, for the most part, a reprint of the edition of Oscar von Gebhardt (Die Psalmen Salomo’s zum ersten Male mit Benutzung der Athoshandschriften und des Codex Casanatensis [Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1895]). Rahlfs frequently incorpo- rated many of von Gebhardt’s conjectural emendations, which are referred to in Rahlfs’ text by the siglum “Gebh.” The remaining conjectural emendations included in Rahlfs’ Greek text are largely derived from the edition of Henry B. Swete (The Psalms of Solomon with the Greek Fragments of the Book of Enoch [Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1899]) and are indicated in Rahlfs’ notes by the siglum “Sw.” This book is basically a reprint of Swete’s earlier edition of the Greek text of PsSal (The Old Testament in Greek According to the Septuagint [vol. 3; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1894] 765–787), but it in- corporates readings from three new manuscripts that were included in von Gebhardt’s text. In one in- stance (17.32), Rahlfs adopted the suggestion first proposed in 1870 by A. Carrière (De Psalterio Salomo- nis disquistionem historico-criticam scripsit [Strasbourg]) that xristo_j ku/rioj, which is preserved in all of PsSal’s manuscripts, should be emended to xristo_j kuri?/ou. -

THE PSALMS… Calls for Thanksgiving and Praise for God’S Deliverance

PSALM 107-150 • 15 composed by David • 1 composed by Solomon (Psalm 127) • Psalm113-118 are known as the “Egyptian Hallel”, recited and sang during the Passover celebration • Psalm 120-134 are known as the ”Psalms of Ascent” • Book Five contains the shortest chapter in the Bible (Psalm 117) and the longest chapter in the Bible (Psalm 119) THE PSALMS… Calls for Thanksgiving and Praise for God’s Deliverance “…Moses gave Israel five books of law, and David gave them five books of Psalms…” CLASSIFICATION PSALM DESCRIPTION Book 1: Psalm 1-41 Penitential 6,32,38,51,102,130,143 Psalms seeking the forgiveness Book 2: Psalm 42-72 of God Acrostic 9,25,34,37,111,112,119,145 Helpful in teaching Book 3: Psalm 73-89 Book 4: Psalm 90-106 Hallelujah 106,113-118,135,146-150 Each begins with “hallelujah”, meaning “praise the Lord” Book 5: Psalm 107-150 Imprecatory 5,28,35,40,55,58,69,83,109 Expressions of anger against enemies and those who do evil Psalms of Degrees or 120-134 Often sang by Jews as traveled Ascent toward Jerusalem to participate in national feasts Messianic 2,8,16,22,23,24,40,41,68, These depict every aspect of 69,72,87,89,102,110,118 the life of Christ “ PSALM 109 “A Psalm of David” (I Samuel 13:14; Acts 13:22) “For the Choir” “…In the awfulness of its anathemas, this Psalm surpasses everything of the kind in the Old Testament…” “…utterly repulsive maledictions inspired by the wildest form of vengeance, make this one of the most questionable hymns …” “…All Scripture is inspired by God (God breathed) and “…carnal passion that is utterly inexcusable…” profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for “…The sudden transition in the psalms from humble devotion to fiery imprecation create an embarrassing problem for the Christian…” training in righteousness so that the man of God may be “…The bitter imprecations of this psalm appear to us as wholly antithetical to the true adequate, equipped for every spirit of Christianity…” good work…”. -

Psalms 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time, the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title, resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72, or 71, was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently, the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. 1See Gleason L. Archer Jr., A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, p. 439. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. Constable www.soniclight.com 2 Dr. Constable's Notes on Psalms 2021 Edition "… there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."1 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. -

Cush the Benjaminite and Psalm Midrash

CUSH THE BENJAMINITE AND PSALM MIDRASH by RODNEY R. HUTTON Trinity Lutheran Seminary, Columbus, OH 43209 Among the various. types of psalm superscriptions are those which associate a given psalm with a specific episode in the life of David. Throughout the history of exegesis it has generally been taken for granted that the superscription of Psalm 7 contains, among other elements, such a historical allusion to some story directly or tangentially related to David, and the phrase 'J'~'-p tzn::>-,i::ii-7:!i i11i1'7 itzriw~ " ... which he sang to to the Lord according to the words of Cush the Benjaminite" has been understood to relate to the activity of one "Cush the Benjaminite. "1 In this study an attempt will be made to clarify three questions pertaining to psalm titles in general and to the title of Psalm 7 in particular. First, how is this particular title related to other similar psalm superscriptions? Second, what is the referent of the superscription of Psalm 7? Who is Cush the Benjaminite, and to what episode in the life of David does the title intend to allude? And third, what was the exegetical intention of the tradent who affixed this particular title to Psalm 7? Psalm Superscriptions and Psalm 7 Those who have considered the superscription of Psalm 7 have often paid too little attention to the syntax of the verse. There are 13 psalm superscriptions which allude to an episode in the life of David, including I. Both Childs (1971, p. 138) and Dahood (1966, p. 40) have questioned whether this superscription is a historical notation.