Pzg Library News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gargoyle Gecko

Gargoyle gecko (Rhacodactylus auriculatus)) Adult Size SVL 4 – 4.5” Overall length 8 inches Lifespan 15-20 years Male/Female Male gargoyle geckos will develop a very noticeable hemipenal bulge just below the Difference vent. The hemipenal bulge develops on males at between 5 months and 9 months old. Compatibility Males should never be housed together. If housing multiple geckos in the same cage make sure to provide 10 gallons per 1 gecko, with plenty of hiding spaces. This will ensure there will be no territorial fighting. Origin New Caledonia (Island grouping between Fiji and Australia.) Climate Humid and tropical jungles, but adapts to household environments well. Day Cycle Nocturnal, working the night shift when their food is available. Temperature 78-82 degrees is fine, cooling down to 70 degrees at night. Use mild heat sources such as a low watt reptile heat mat or ceramic bulb. Lighting Even though gargoyle geckos are nocturnal, use a high quality UVA light to stimulate appetite and for emotional health. Humidity Relative humidity should be kept at %50-%70. Keep humid with frequent misting and a shallow water bowl. Habitat/Territory Gargoyle geckos are arboreal with special feet that allow them to climb even the smoothest glass. Substrate/Bedding Coconut fiber, or vermiculite can be used, but the substrate is not important as they will spend most of their time hiding in plants. Moss helps provide extra moisture and humidity. Hiding Place/Den Provide plenty of plants – either artificial or real – for gargoyle geckos as they need places to hide. Wilmette Pet Center 625 Green Bay Road, Wilmette 847-251-6750 Page 1 of 2 www.wilmettepetcenter.com Updated 4.2019 Cage Type Ten gallon aquariums or critter cages with screen tops work well for gargoyle geckos. -

The Habitat Use of Two Species of Day Geckos (Phelsuma Ornata and Phelsuma Guimbeaui) and Implications for Conservation Management in Island Ecosystems

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 9(2):551−562. Submitted: 24 June 2014; Accepted: 29 October 2014; Published: 31 December 2014. THE HABITAT USE OF TWO SPECIES OF DAY GECKOS (PHELSUMA ORNATA AND PHELSUMA GUIMBEAUI) AND IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT IN ISLAND ECOSYSTEMS 1,2,5 3,4 3 2 MICHAEL JOHN BUNGARD , CARL JONES , VIKASH TATAYAH , AND DIANA J. BELL 1Whitley Wildlife Conservation Trust, Paignton, Devon, TQ4 7EU, UK 2Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Conservation, School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Norfolk, NR4 7TJ, UK 3Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, Grannum Road, Vacoas, Mauritius 4Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Les Augrès Manor, Trinity, Jersey JE3 5BP, Channel Islands, UK 5Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Many fragile ecosystems across the globe are islands with high numbers of endemic species. Most tropical islands have been subject to significant landscape alteration since human colonisation, with a consequent loss of both habitat and those specialist species unable to adapt or disperse in the face of rapid change. Day geckos (genus Phelsuma) are thought to be keystone species in their habitats and are, in part, responsible for pollination of several endangered endemic plant species. However, little is known about key drivers of habitat use which may have conservation implications for the genus. We assessed the habitat use of two species of Phelsuma (Phelsuma ornata and Phelsuma guimbeaui) in Mauritius. Both species showed a strong affinity with tree trunks, specific tree architecture and are both restricted to native forest. Tree hollows or cavities are also important for both species and are a rarely documented microhabitat for arboreal reptiles. -

Two New Species of the Genus Bavayia (Reptilia: Squamata: Diplodactylidae) from New Caledonia, Southwest Pacific!

Pacific Science (1998), vol. 52, no. 4: 342-355 © 1998 by University of Hawai'i Press. All rights reserved Two New Species of the Genus Bavayia (Reptilia: Squamata: Diplodactylidae) from New Caledonia, Southwest Pacific! AARON M. BAUER, 2 ANTHONY H. WHITAKER,3 AND Ross A. SADLIER4 ABSTRACT: Two new species ofthe diplodactylid gecko Bavayia are described from restricted areas within the main island ofNew Caledonia. Both species are characterized by small size, a single row of preanal pores, and distinctive dorsal color patterns. One species is known only from the endangered sclerophyll forest of the drier west coast of New Caledonia, where it was collected in the largest remaining patch of such habitat on the Pindai" Peninsula. The second species occupies the maquis and adjacent midelevation humid forest habitats in the vicinity of Me Adeo in south-central New Caledonia. Although relation ships within the genus Bavayia remain unknown, the two new species appear to be closely related to one another. BAVAYIA IS ONE OF THREE genera of carpho tion of the main island. The two most wide dactyline geckos that are endemic to the New spread species, B. cyclura and B. sauvagii, are Caledonian region. Seven species are cur both probably composites of several mor rently recognized in the genus (Bauer 1990). phologically similar, cryptic sibling species. Three of these, B. crassicollis Roux, B. cy Recent field investigations on the New Cale clura (Giinther), and B. sauvagii (Boulenger), donian mainland have revealed the presence are relatively widely distributed, with popula of two additional species of Bavayia. Both tions on the Isle of Pines (Bauer and Sadlier are small, distinctively patterned, and appar 1994) and the Loyalty Islands (Sadlier and ently restricted in distribution. -

RVC Exotics Service CRESTED GECKO CARE

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH CRESTED GECKO CARE The Crested gecko (Rhacodactylus ciliatus) originates from the islands of New Caledonia where the species was believed to be extinct until 1994 when it was subsequently rediscovered. In its natural environment, it can be found resting in rainforests, sleeping in trunk hollows or leaf litter, and only becomes active at night. Similar to other geckos, it can shed its tail as a defence mechanism (autotomy), but unlike others it lacks an ability to regenerate the tail, so care should be taken while handling. Geckos may live 10-15 years if looked after correctly. HOUSING • As large a vivarium as possible should be provided to enable room for exercise, and a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). Wooden or fibreglass vivaria are ideal as this provides the lizard with some visual security and ventilation can be provided at lizard level. • Good ventilation is required and additional ventilation holes may need to be created. • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. One hide should contain damp moss, kitchen towel or vermiculite to provide a humid environment for shedding. • Substrates suitable for housing lizards include newspaper, Astroturf and some of the commercially available substrates. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. -

A New Locality for Correlophus Ciliatus and Rhacodactylus Leachianus (Sauria: Diplodactylidae) from Néhoué River, Northern New Caledonia

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 553-555 (2015) (published online on 06 December 2015) A new locality for Correlophus ciliatus and Rhacodactylus leachianus (Sauria: Diplodactylidae) from Néhoué River, northern New Caledonia Mickaël Sanchez1, Jean-Jérôme Cassan2 and Thomas Duval3,* Giant geckos from New Caledonia (Pacific Ocean) We observed seven native gecko species: Bavayia are charismatic nocturnal lizards. This paraphyletic (aff.) cyclura (n=1), Bavayia (aff.) exsuccida (n=1), group is represented by three genera, Rhacodactylus, Correlophus ciliatus (n=1), Dierrogekko nehoueensis Correlophus and Mniarogekko, all endemic to Bauer, Jackman, Sadlier and Whitaker, 2006 (n=1), New Caledonia (Bauer et al., 2012). Rhacodactylus Eurydactylodes agricolae Henkel and Böhme, 2001 leachianus (Cuvier, 1829) is largely distributed on the (n=1), Mniarogekko jalu Bauer, Whitaker, Sadlier and Grande Terre including the Île des Pins and its satellite Jackman, 2012 (n=1) and Rhacodactylus leachianus islands, whereas Correlophus ciliatus Guichenot, 1866 (n=1). Also, the alien Hemidactylus frenatus Dumeril is mostly known in the southern part of the Grande and Bibron, 1836 (n=3) has been sighted. The occurrence Terre, the Île des Pins and its satellite islands (Bauer of C. ciliatus and R. leachianus (Fig. 2 and 3) represent et al., 2012). Here, we report a new locality for both new records for this site. Both gecko species were species in the north-western part of Grande Terre, along observed close to the ground, at a height of less than the Néhoué River (Fig. 1). 1.5 m. The Néhoué River is characterized by gallery forests It is the first time that R. leachianus is recorded in the growing on deep alluvial soils. -

Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus Frenatus)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 27: 69–79On (2015) the origin of South American populations of the common house gecko 69 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.27.5437 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions On the origin of South American populations of the common house gecko (Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus frenatus) Omar Torres-Carvajal1 1 Museo de Zoología, Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Avenida 12 de Octubre 1076 y Roca, Apartado 17-01-2184, Quito, Ecuador Corresponding author: Omar Torres-Carvajal ([email protected]) Academic editor: Sven Bacher | Received 11 June 2015 | Accepted 27 August 2015 | Published 15 September 2015 Citation: Torres-Carvajal O (2015) On the origin of South American populations of the common house gecko (Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus frenatus). NeoBiota 27: 69–79. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.27.5437 Abstract Hemidactylus frenatus is an Asian gecko species that has invaded many tropical regions to become one of the most widespread lizards worldwide. This species has dispersed across the Pacific Ocean to reach Ha- waii and subsequently Mexico and other Central American countries. More recently, it has been reported from northwestern South America. Using 12S and cytb mitochondrial DNA sequences I found that South American and Galápagos haplotypes are identical to those from Hawaii and Papua New Guinea, suggest- ing a common Melanesian origin for both Hawaii and South America. Literature records suggest that H. frenatus arrived in Colombia around the mid-‘90s, dispersed south into Ecuador in less than five years, and arrived in the Galápagos about one decade later. -

Notes on Phyllodactylus Palmeus (Squamata; Gekkonidae); a Case Of

Captive & Field Herpetology Volume 3 Issue 1 2019 Notes on Phyllodactylus palmeus (Squamata; Gekkonidae); A Case of Diurnal Refuge Co-inhabitancy with Centruroides gracilis (Scorpiones: Buthidae) on Utila Island, Honduras. Tom Brown1 & Cristina Arrivillaga1 1Kanahau Utila Research and Conservation Facility, Isla de Utila, Islas de la Bahía, Honduras Introduction House Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) (Wilson and Cruz Diaz, 1993: McCranie et al., 2005). The Honduran Leaf-toed Palm Gecko Over seventeen years following the (Phyllodactylus palmeus) is a medium-sized Hemidactylus invasion of Utila (Kohler, 2001), (maximum male SVL = 82 mm, maximum our current observations spanning from 2016 female SVL = 73 mm) species endemic to -2018 support those of McCranie & Hedges Utila, Roatan and the Cayos Cochinos (2013) in that P. palmeus is now primarily Acceptedarchipelago (McCranie and Hedges, 2013); Manuscript restricted to undisturbed forested areas, and islands which constitute part of the Bay Island that H. frenatus is now unequivocally the most group on the Caribbean coast of Honduras. The commonly observed gecko species across species is not currently evaluated by the IUCN Utila. We report that H. frenatus has subjugated Redlist, though Johnson et al (2015) calculated all habitat types on Utila Island, having a an Environmental Vulnerability Score (EVS) of practically all encompassing distribution 16 out of 20 for this species, placing P. occupying urban and agricultural areas, palmeus in the lower portion of the high hardwood, swamp, mangrove and coastal vulnerability category. To date, little forest habitats and even areas of neo-tropical information has been published on the natural savannah (T. Brown pers. observ). On the other historyC&F of P. -

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist Reptiles

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist ow if there are so many lizards then they should make tasty N meals for someone. Many of the lizard-eaters come from their Reptiles own kind, especially the snake-like legless lizards and the snakes themselves. The former are completely harmless to people but the latter should be left alone and assumed to be venomous. Even so it odern reptiles are at the most diverse in the tropics and the is quite safe to watch a snake from a distance but some like the Md rylands of the world. The Australian arid zone has some of the Mulga Snake can be curious and this could get a little most diverse reptile communities found anywhere. In and around a disconcerting! single tussock of spinifex in the western deserts you could find 18 species of lizards. Fowlers Gap does not have any spinifex but even he most common lizards that you will encounter are the large so you do not have to go far to see reptiles in the warmer weather. Tand ubiquitous Shingleback and Central Bearded Dragon. The diversity here is as astonishing as anywhere. Imagine finding six They both have a tendency to use roads for passage, warming up or species of geckos ranging from 50-85 mm long, all within the same for display. So please slow your vehicle down and then take evasive genus. Or think about a similar diversity of striped skinks from 45-75 action to spare them from becoming a road casualty. The mm long! How do all these lizards make a living in such a dry and Shingleback is often seen alone but actually is monogamous and seemingly unproductive landscape? pairs for life. -

1 the Multiscale Hierarchical Structure of Heloderma Suspectum

The multiscale hierarchical structure of Heloderma suspectum osteoderms and their mechanical properties. Francesco Iacoviello a, Alexander C. Kirby b, Yousef Javanmardi c, Emad Moeendarbary c, d, Murad Shabanli c, Elena Tsolaki b, Alana C. Sharp e, Matthew J. Hayes f, Kerda Keevend g, Jian-Hao Li g, Daniel J.L. Brett a, Paul R. Shearing a, Alessandro Olivo b, Inge K. Herrmann g, Susan E. Evans e, Mehran Moazen c, Sergio Bertazzo b,* a Electrochemical Innovation Lab, Department of Chemical Engineering University College London, London WC1E 7JE, UK. b Department of Medical Physics & Biomedical Engineering University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK. c Department of Mechanical Engineering University College London, London WC1E 7JE, UK. d Department of Biological Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA. e Department of Cell & Developmental Biology University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK. f Department of Ophthalmology University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK. g Department of Materials Meet Life Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa) Lerchenfeldstrasse 5, CH-9014, St. Gallen, Switzerland. * Correspondence: Sergio Bertazzo [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 2076790444 1 Abstract Osteoderms are hard tissues embedded in the dermis of vertebrates and have been suggested to be formed from several different mineralized regions. However, their nano architecture and micro mechanical properties had not been fully characterized. Here, using electron microscopy, µ-CT, atomic force microscopy and finite element simulation, an in-depth characterization of osteoderms from the lizard Heloderma suspectum, is presented. Results show that osteoderms are made of three different mineralized regions: a dense apex, a fibre-enforced region comprising the majority of the osteoderm, and a bone-like region surrounding the vasculature. -

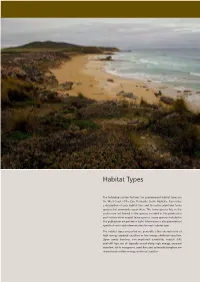

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

XIV Jornades Herpetològiques Catalanes

XIV Jornades Herpetològiques Catalanes Marçà (Priorat) 10 i 11 de novembre de 2012 ORGANITZADES PER: AMB LA COL·LABORACIÓ DE: SOCIETAT CATALANA D’HERPETOLOGIA XIV JORADES HERPETOLÒGIQUES CATALAES Llibre de Resums Marçà (Priorat, Catalunya) 10 i 11 d’octubre de 2012 Organitzades per: Socetat Catalana d’Herpetologia Amb la col·laboració de: Grup d’Estudi i Protecció dels Ecosistemes Catalans – Ecologistes de Catalunya Ajuntament de Marçà Institució Catalana d’Història atural 2 PRESETACIÓ DE LES XIV JORADES HERPETOLÒGIQUES CATALAES Marçà (Priorat, Catalunya) 10 i 11 d’octubre de 2012 Des de la Societat Catalana d’Herpetologia (SCH), i també des de les enti- tats col·laboradores Grup d’Estudi i Protecció dels Ecosistemes Catalans – Ecologistes de Catalunya (GEPEC.EdC), Ajuntament de Marçà i la Institu- ció Catalana d’Història Natural (ICHN), es fa un esforç important perquè les Jornades Herpetològiques de Marçà esdevinguin el punt de trobada tant d’herpetòlegs professionals com d’afeccionats als amfibis i rèptils. En aquest sentit, i com en les anteriors edicions, l’esperit de les Jornades dóna cabuda a estudiants i persones que s’inicien en aquest món, en emular una escola de joves naturalistes a l’estil d’antigues trobades que s’organitzaven, ja fa dècades, al nostre país. Amb la presència de científics d’alt nivell, i alhora pedagògics, amens i propers, amb presentacions de gran qualitat, esperem satisfer les expectatives de tothom, i que ens trobem tots, aquest cap de setmana a Marçà, on podrem preguntar, aprendre, compartir vivèn- cies, inquietuds, etc. Os desitgem que gaudiu d’aquestes Jornades SOCIETAT CATALAA D’HERPETOLOGIA SOCIETAT CATALANA D’HERPETOLOGIA Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona.