Balancing Uniformity and Liveliness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MBA Seattle Auction House Great Northwest Estates! Antiquities and Design – TIMED AUCTION Bid.Mbaauction.Com Items Begin to Close at 10AM on Thursday 6/24

MBA Seattle Auction House Great Northwest Estates! Antiquities and Design – TIMED AUCTION bid.mbaauction.com Items begin to close at 10AM on Thursday 6/24 25% Buyers Premium Added to All Bids Serigraph Framed- 46x34" 3018 Modern Artist Proof Signed Embossed ALL ITEMS MUST BE PICKED UP Serigraph Framed- 46x34" WITHIN 7 DAYS OF AUCTION CLOSE! 3019 Designer Gold Leaf Buddha Gallery Framed Lithograph- 53x42" Bid.mbaauction.com 3020 John Richard Collection Persian Horse Painting on Cloth Framed- 47x67" Lot Description 3021 Large Egyptian Hieroglyph Painting on Papyrus Framed- 38x75" 3000 Italian Leather Bound Stacking Book End 3022 K. Berata Large Balinese Painting of Nude Table with Drawers- 21x21x15" Women Framed- 42x82" 3001 Scroll Arm Upholstered Chair- 33x25x28" 3023 Ambrogin Modern Collage 4 Panel Screen- 3002 Bianchi Barbara Inlaid Italian Chess Set 37x73" with Board- 20x20" 3024 Pascal Cucaro Enameled Still Life Plaque in 3003 Pair Vintage French Marble Table Lamps- Gilt Frame- 15x13" 29" 3025 Pascal Cucaro Enameled Modern Figures 3004 Designer Wrought Iron 'Fasces' Glass Top Plaque in Gilt Frame- 15x13" Coffee Table- 20x47x23" 3026 Hand Colored 'Piper Indicum Medium' 3005 Victorian Iron Marble Top Floral Side Pepper Plant Botanical Framed Etching- Stand- 33x20x12" 30x26" 3006 Old Italian Inlaid Mahogany 2 Drawer 3027 Antique Gilt Archtop Framed Mirror- Stand- 29x22x12" 45x29" 3007 Pair Designer Monkey Table Lamps- 26" 3028 Italian Gilt Decorated Hanging Barometer- 3008 Pair Chapman Brass Designer Table Lamps- 35x19" 36" 3029 Bombay -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 6, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society 1-1945 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 6, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 1945 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE VOL. VI NO.2 JAN. 1945 CONTENTS Black Lucy's Garden. Adelaide and Ripley P. Bullen • • 17 The Dolmen on Martha's Vineyard. Frederick Johnson .•.••• • 29 PUBLISHED BY THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL. SOCIETY BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS Douglas S. By_raJ Editor, Box'll, Andover, Massachusetts rHE (l~M·NT C. MAXw.m lI11RAR'I " STATE C ·.L'=G~ \ IRIJ)GEWA~ MASSACHU.fTTS ~.. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2010 Massachusetts Archaeological Society. BLACK LUCY'S GARDEN Adelaide K. and Ripley P. Bullen While excavating the Stickney Site, M12/?? , on the west side of Woburn Street in the Ballardvale section of Andover, Mass achusetts, wha~ was presumed to be Colonial pottery was found in association with Indian material. (1) A cellar hole was found just to the south, at the foot of the knoll con taining the Indian site, Fig.l. As it was hoped that this might offer an opportunity to date the pottery, the cellar hole was ex t- cavated. -

)&F1y3x CHAPTER 69 CERAMIC PRODUCTS XIII 69-1 Notes 1. This

)&f1y3X CHAPTER 69 CERAMIC PRODUCTS XIII 69-1 Notes 1. This chapter applies only to ceramic products which have been fired after shaping. Headings 6904 to 6914 apply only to such products other than those classifiable in headings 6901 to 6903. 2. This chapter does not cover: (a) Products of heading 2844; (b) Articles of chapter 71 (for example, imitation jewelry); (c) Cermets of heading 81l3; (d) Articles of chapter 82; (e) Electrical insulators (heading 8546) or fittings of insulating material (heading 8547); (f) Artificial teeth (heading 9021); (g) Articles of chapter 91 (for example, clocks and clock cases); (h) Articles of chapter 94 (for example, furniture, lamps and lighting fittings, prefabricated buildings); (ij) Articles of chapter 95 (for example, toys, games and sports equipment); (k) Articles of heading 9606 (for example, buttons) or of heading 9614 (for example, smoking pipes); or (l) Articles of chapter 97 (for example, works of art). Additional U.S. Notes 1. For the purposes of this chapter, a "ceramic article" is a shaped article having a glazed or unglazed body of crystalline or substantially crystalline structure, the body of which is composed essentially of inorganic nonmetallic substances and is formed and subsequently hardened by such heat treatment that the body, if reheated to pyrometric cone 020, would not become more dense, harder, or less porous, but does not include any glass articles. 2. For the purposes of headings 6902 and 6903, the term "refractory" is applied to articles which have a pyrometric cone equivalent of at least 1500°C when heated at 60°C per hour (pyrometric cone 18). -

Conservation Takes a Latin Twist with Festival Del

INSIDE WEEK OF JUNE 15-21,-21, 20172017 www.FloridaWeekly.com Vol. VII, No. 34 • FREE INSIDE: • Why Florida has lost its place in the film industry. A12 Y THE NUMBERSdits offered • Productions that might have shot here if we offered BY THE NUMBERStax cre kers. % of tax credits offeredma . incentives. A12 by Georgia to filmmakers. Florida offers 0% currently Y Billions of dollars of economic impact the Dierks film industry had in Georgia in 2016. Feature film and television pro- Country singer Bentley says he’s ductions made in Georgia in 2016. happiest in front of an audience. B1 TION BY ERIC RADDATZ / FLORIDA WEEKL FLORIDA / RADDATZ ERIC BY TION PHOTO ILLUSTRA PHOTO ▲ Top: Baby Networking Groot from ▲ Pantelides PR Consulting ribbon “Guardians From cutting ceremony in Jupiter. A17 of the the top: Galaxy ■ Killing Florida tax benebenefitsfits “Bloodline,” 2,” which “Miami V filmed in forfor filmfifilm companiescompcomp means “Ballers,”ice,” Georgia. “Burn Notice” and ▲ states like GeorgiaGe are now At right: “Dolphin “Iron Man reapingreaping the eeconomic Tale” were 3” shot in shot with a Florida. benefitsbeneenefitsfits ffrfromro production Florida backdrop, Real estate wewe once eenjoyedn benefitting our image Majestic Mediterranean at BY ERERICERICRIR C RADDATZRADDA and economy Medalist. A18 eraddatz@fleraddatz@flatz@fl ooridaweekly.comoridarida . ▲ Dwayne OR STATE LEADERS WHO TOUT Johnson’ s jobs and the economy first, “Ballers” the fumble appears huge. used to film In the last 36 months, Florida’s here before incentives refusal to offer tax incentives to more dried up than 50 makers of movies and televi- . sion shows who first contacted officials aiming to bring their business here has cost the Sunshine State as much as $875 million. -

Hts Chapter 69 Ceramic Products

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2010) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes CHAPTER 69 CERAMIC PRODUCTS XIII 69-1 Notes 1. This chapter applies only to ceramic products which have been fired after shaping. Headings 6904 to 6914 apply only to such products other than those classifiable in headings 6901 to 6903. 2. This chapter does not cover: (a) Products of heading 2844; (b) Articles of heading 6804; (c) Articles of chapter 71 (for example, imitation jewelry); (d) Cermets of heading 8113; (e) Articles of chapter 82; (f) Electrical insulators (heading 8546) or fittings of insulating material (heading 8547); (g) Artificial teeth (heading 9021); (h) Articles of chapter 91 (for example, clocks and clock cases); (ij) Articles of chapter 94 (for example, furniture, lamps and lighting fittings, prefabricated buildings); (k) Articles of chapter 95 (for example, toys, games and sports equipment); (l) Articles of heading 9606 (for example, buttons) or of heading 9614 (for example, smoking pipes); or (m) Articles of chapter 97 (for example, works of art). Additional U.S. Notes 1. For the purposes of headings 6902 and 6903, the term "refractory" is applied to articles which have a pyrometric cone equivalent of at least 1500EC when heated at 60EC per hour (pyrometric cone 18). Refractory articles have special properties of strength and resistance to thermal shock and may also have, depending upon the particular uses for which designed, other special properties such as resistance to abrasion and corrosion. 2. For the purposes of heading 6902, a brick which contains both chromium and magnesium is classifiable according to which of those components (expressed as Cr2O3 or MgO, respectively) is the greater by weight. -

The Studio Potter Archives

ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM CERAMICS RESEARCH CENTER THE STUDIO POTTER ARCHIVES 2015 Contact Information Arizona State University Art Museum Ceramics Research Center P.O. Box 872911 Tempe, AZ 85287-2911 http://asuartmuseum.asu.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Collection Overview 3 Administrative Information 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope and Content Note 4 Arrangement 5 Series 1: Magazine Issues: Volume 1, No. 1 – Volume 32, No. 2 Volume 1, No. 1 5 Volume 2, Nos. 1-2 6 Volume 3, Nos. 1-2 7 Volume 4, Nos. 1-2 9 Volume 5, Nos. 1-2 11 Volume 6, Nos. 1-2 13 Volume 7, Nos. 1-2 15 Volume 8, Nos. 1-2 17 Volume 9, Nos. 1-2 19 Volume 10, Nos. 1-2 21 Volume 11, Nos. 1-2 23 Volume 12, Nos. 1-2 26 Volume 13, Nos. 1-2 29 Volume 14, Nos. 1-2 32 Volume 15, Nos. 1-2 34 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 38 Volume 17, Nos. 1-2 40 Volume 18, Nos. 1-2 43 Volume 19, Nos. 1-2 46 Volume 20, Nos. 1-2 49 Volume 21, Nos. 1-2 53 Volume 22, Nos. 1-2 56 Volume 23, Nos. 1-2 58 Volume 24, Nos. 1-2 61 Volume 25, Nos. 1-2 64 Volume 26, Nos. 1-2 67 1 Volume 27, Nos. 1-2 69 Volume 28, Nos. 1-2 72 Volume 29, Nos. 1-2 74 Volume 30, Nos. 1-2 77 Volume 31, Nos. 1-2 81 Volume 32, Nos. 1-2 83 Series 2: Other Publications Studio Potter Network News 84 Studio Potter Book 84 Series 3: Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Images Miscellaneous Manuscripts 85 Miscellaneous Images 86 Series 4: 20th Anniversary Collection 86 Series 5: Administration Daniel Clark Foundation/Studio Potter Foundation 87 Correspondence 88 Miscellaneous Files 88 Series 6: Oversized Items 88 Series 7: Audio Cassettes 89 Series 8: Magazine Issues: Volume 33, No. -

Texaco, Petroliana, Toys & Models, Antiques & Estate Auction 3/20 NEW 16% Buyers Premium 717 S Third St Renton, WA

Texaco, Petroliana, Toys & Models, Antiques & Estate Auction 3/20 NEW 16% Buyers Premium 717 S Third St Renton, WA (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTIONS 12 (4) Metal Model Kits MIB & Unbuilt. Includes Western Models 1/24 scale Ferrari Lots #1000's Ends 7:00PM 250 GTO, AMR Maserati Tipo 60-61 Lots #2000's Ends 7:30PM Birdcage-Riverside 1/43 scale, AMR Ferrari Lots #3000's Ends 8:00PM GTO 4 Litres 1/43 scale, and AMR Ford MK 2 LM66 1/43 scale. FIRST #1-123 LOTS WILL BE HOSTED 13 Vintage Neptune Tin Battery Operated Tug ON LIVEAUCTIONEERS Boat 14.5" MIB. Japan T.M. Toys. 14 Maserati T-61 Birdcage Tipo Models by Lot Description CMA 6.25" MIB. Comes with plexiglass and 1 Franklin Mint 1957 Corvette Cutaway marble base display cube and is unbuilt. 283 Engine Model 1:6 Scale 7". 15 De Lorean 1:18 Scale Model Metal Diecast 2 Offenhauser GMP 1:6 Scale Model Car by Sun Star MIB. Engine 5.5" 16 Group (3) HO Model Kits Railroad Buildings 3 Strombecker Cheetah 1960's Slot Car & Structures by Builders in Scale. Includes Model Kit MIB 1/24 Scale. Model The Waterfront, Pitkin City Hall and No.8510-795, Unbuilt Tidewater Wharf. All MIB and unbuilt 4 Cox Cheetah 1960's Slot Car Model Kit 17 Group of (20) Vintage AFX, Tyco & Other MIB 1/24 Scale. Unbuilt Brand Slot Cars and Parts. 5 Group (5) Don Garlit's Drag Racer 18 Vintage Marx Charlie McCarthy Benzine Model Kits MIB. All unbuilt Buggy Crazy Car Tin Windup. -

NONMETALLIC MINERALS A^Fd PRODUCTS TARIFF SCHEDULES of the UNITED STATES

223 SCHEDULE 5. - NONMETALLIC MINERALS A^fD PRODUCTS TARIFF SCHEDULES OF THE UNITED STATES SCHEDULE 5. - NONMETALLIC MINERALS AND PRODUCTS 224 Part 1 - Nonmetallic Minerals and Products, Except Ceramic Products and Glass and Glass Products A. Hydraulic Cement; Concrete; Concrete Products B. Lime, Gypsum, and Plaster Products C. Stone and Stone Products D. Mica and Mica Products E. Graphite and Related Products F. Asbestos and Asbestos Products G. Abrasives and Abrasive Articles H. Gems, Gemstones, and Articles Thereof; Industrial Diamonds J. Miscellaneous Nonmetallic Minerals and Products K. Nonmetallic Minerals and Products Not Specially Provided For Part 2 - Ceramic Products A. Refractory and Heat-Insulating Articles B. Ceramic Construction Articles C. Table, Kitchen, Household, Art and Ornamental Pottery D. Industrial Ceramics E. Ceramic Articles Not Specially Provided For Part 3 - Glass and Glass Products A. Glass in the Mass; Glass in Balls, Tubes, Rods, and Certain Other Forms; Foam Glass; Optical Glass; and Glass Fibers and Products Thereof B. Flat Glass and Products Thereof C. Glassware and Other Glass Products D. Glass Articles Not Specially Provided For TARIFF SCHEDULES OF THE UNITED STATES SCHEDULE 5. - NONMETALLIC MINERALS AND PRODUCTS Part 1; - Nonmetallic Minerals and Products, Except Ceramic Products and Glass and Glass Products 225 Rates of Duty PART 1. - NONMETALLIC MINERALS AND PRODUCTS, EXCEPT CERAMIC PRODUCTS AND GLASS AND GLASS PRODUCTS Subpart A. - Hydraulic Cement; Concrete; Concrete Products Subpart A headnotes: I. For the purposes of this subpart — (a) the term "cement" means cementing materials without added sand, gravel, or other aggregate; and (b) the term "concrete" means a composite of cementing materials (including bitumens and resins) with added sand, gravel, or other mineral aggregate; and (c) the term "tiles" does not include any article 1.25 inches or more In thickness. -

Property of the Restaurant Ware Collectors Network

THE OF WARE NETWORK PROPERTY RESTAURANT COLLECTORS THE OF WARE 0-= OI8.IMGIJI8 ..:.=O NETWORK PROPERTY RESTAURANT COLLECTORS ~ ONONDAGA POTTERY COMPANY I Iyaacu•• , N.Y. • The building ofthe Onondaga Pottery has been the work ofthree generations since the Company was founded in 1871. The success of this organization has been due primarily to two factors closely related to one another. The first of these is the character of the men and women who THE comprise the Onondaga Pottery today and also the character ofthose who OF have made up this organization in the pastWAREand who still are more a part of us than we may realize. The second is the spirit of mutual respect, confi dence, and goodwill in which we all have worked together through the NETWORK years. This spirit PROPERTYcannot be expressed adequately in words, but it is ex plained partly in the opening sentence ofour Statement of Policy: RESTAURANT " The first principle ofthe Onondaga Pottery is that this business exists to be ofservice -tothe public which buys our china-toCOLLECTORSthe people working in this organization-to the stockholders who provide our plants and the equipment with which we work; that the interests ofthese three groups are essentially the same; that these, our common interests, can be served well only as we ofthe Pottery serve each other well." 2 COI'YItlGHT IU6, O!'lOHO....GA !'OmltY COM~..."". SlltACUSf, I'l. Y. Fine chinaware is an exception in this mechanistic age, in which machines have displaced for the most part human skill. The making oftrue china remains largely a humanjob, reflecting the diligence and loyalty and skill ofthose who make it. -

Local Lndustry Focuses on White Earthenware the Farrars Had Been

Local lndustry Focuses on White Earthenware The Farrars had been pioneers. Moses raised subscribers in St. Johns and Farrar had introduced stoneware to St. lberville and organized a joint stock Johns in 1840. George Whitfield Farrar compsny, the St. Johns Stone China- had given up control of the firm in 1866 ware Company, in 1873." Another so that he could be free to focus on a potter, William Livesley, was recruited new project: the production of white (probably from Trenton) to be the chief earthenware. No one had yet started to technician of the firm. Land was produce this in Canada although potters purchased at the corner of Grant and in Trenton, New Jersey had spent a Partition Streets, a St. Johns contractor decade establishing a market and was signed on6' and work began on making "white granite" ware the construction of the plant. It took more specialty of the US. industry. This than a year for the factory to be readied "white granite" body was somewhat for the launching of home-made harder than the hardest English white "granite" ware on the Canadian market earthenware but not so hard as the but by August 28, 1874 the first ship- vitreous "ironstone" ware patented by ment of the company's goods was sent Mason's in Staffordshire in 1813. The off. As other enterprises crashed around American product had become a com- them, the St. Johns Stone Chinaware mercial success by 1873 primarily by Company cleared more than 53,000 in concentrating on heavy hotel and its first seven months 66 and hoped to restaurant ware. -

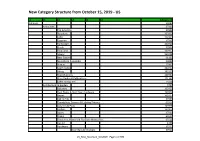

New Category Structure from October 15, 2019 - US

New Category Structure from October 15, 2019 - US L1 L2 L3 L4 L5 L6 Category ID Antiques 20081 Antiquities 37903 The Americas 37908 Byzantine 162922 Celtic 162923 Egyptian 37905 Far Eastern 162916 Greek 37906 Holy Land 162917 Islamic 162918 Near Eastern 91101 Neolithic & Paleolithic 66834 Roman 37907 South Italian 162919 Viking 162920 Reproductions 162921 Price Guides & Publications 171169 Other Antiquities 73464 Architectural & Garden 4707 Balusters 162925 Barn Doors & Barn Door Hardware 162926 Beams 162927 Ceiling Tins 37909 Chandeliers, Sconces & Lighting Fixtures 63516 Columns & Posts 162928 Corbels 162929 Doors 37910 Finials 63517 Fireplaces, Mantels & Fireplace Accessories 63518 Garden 4708 Hardware 37911 Door Bells & Knockers 37912 US_New_Structure_Oct2019 - Page 1 of 590 L1 L2 L3 L4 L5 L6 Category ID Door Knobs & Handles 37914 Door Plates & Backplates 37916 Drawer Pulls 162933 Escutcheons & Key Hole Covers 162934 Heating Grates & Vents 162935 Hinges 184487 Hooks, Brackets & Curtain Rods 37913 Locks, Latches & Keys 37915 Nails 162930 Screws 162931 Switch Plates & Outlet Covers 162932 Other Antique Hardware 66637 Pediments 162936 Plumbing & Fixtures 167948 Signs & Plaques 63519 Stained Glass Windows 151721 Stair & Carpet Rods 112084 Tiles 37917 Weathervanes & Lightning Rods 37918 Windows, Shutters & Sash Locks 63520 Reproductions 162937 Price Guides & Publications 171170 Other Architectural Antiques 1207 Asian Antiques 20082 Burma 162938 China 37919 Amulets 162939 Armor 162940 Baskets 37920 Bells 162941 Bowls 37921 Boxes 37922 Bracelets -

A Magazine for Clay and Glass

Volume 45 Number 1 | Spring 2021 FUSION A MAGAZINE FOR CLAY AND GLASS FORCLAY MAGAZINE A FUSION A MAGAZINE FOR CLAY AND GLASS Editor: Margot Lettner Advertising: FUSION Design & Production: Derek Chung Communications IN THIS ISSUE Date of Issue: Spring 2021 FUSION Magazine is published three Editor’s Note times yearly by FUSION: The Ontario Margot Lettner . 5 Clay and Glass Association © 2021. All rights reserved. ISSN 0832-9656; in Canadian Periodical Index. The Edith Heath: The Making of a Committed Life views expressed by contributors are Margot Lettner . 6 not necessarily those of FUSION. Website links are based on best available information as of issue date. Paired Samaras: Please address editorial material to [email protected]. or to FUSION A Conversation with Andrea Poorter and Genevieve Patchell Magazine, 1444 Queen Street East, Toronto, Ontario, Aitak Sorahitalab, in conversation with Canada M4L 1E1. FUSION Magazine subscription is a benefit of Andrea Poorter and Genevieve Patchell . 16 FUSION membership and is included in membership fees. FUSION Magazine subscriptions are also Hands-on Jurying: Holding a Virtual Ceramics Exhibition in a Pandemic available. To apply for a FUSION membership, or to purchase a one year subscription (three issues), Elizabeth Davies . 22 please visit www.clayandglass.on.ca/page-752463 for details. Back issues are available. FUSION Magazine Spotlight, Featured Emerging Artist – Clay FUSION is a not-for-profit, registered charitable Zara Gardner . 25 organization (122093826 RR0001). We do not make our subscribers’ names available to FUSION Magazine Spotlight, Featured Emerging Artist – Glass anyone else. Lauri Maitland . 26 FUSION BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2020-2021 President Wendy Hutchinson Chair, Clay and Glass Show ON THE COVER Chair, Nominations Chair, Makers Crit Edith Heath examining a clay-rich wall Chair, Conference of earth with her ceramics class from Secretary Alison Brannen the California College of Arts and Chair, Makers Meet Treasurer Bep Schippers Crafts, ca.1955–1957.