Formatted Finaldraftuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Latin(O) Americanos: Transoceanic Diasporas And

DEBATES: GLOBAL LATIN(O) AMERICANOS Global Latin(o) Americanos: Transoceanic Diasporas and Regional Migrations by MARK OVERMYER-VELÁZQUEZ | University of Connecticut | [email protected] and ENRIQUE SEPÚLVEDA | University of Saint Joseph, Connecticut | [email protected] Human mobility is a defining characteristic By the end of the first decade of the Our use of the term “Global Latin(o) of our world today. Migrants make up one twenty-first century the contribution of Americanos” places people of Latin billion of the globe’s seven billion people— Latin America and the Caribbean to American and Caribbean origin in with approximately 214 million international migration amounted to over comparative, transnational, and global international migrants and 740 million 32 million people, or 15 percent of the perspectives with particular emphasis on internal migrants. Historic flows from the world’s international migrants. Although migrants moving to and living in non-U.S. Global South to the North have been met most have headed north of the Rio Grande destinations.5 Like its stem words, Global in equal volume by South-to-South or Rio Bravo and Miami, in the past Latin(o) Americanos is an ambiguous term movement.1 Migration directly impacts and decade Latin American and Caribbean with no specific national, ethnic, or racial shapes the lives of individuals, migrants have traveled to new signification. Yet by combining the terms communities, businesses, and local and destinations—both within the hemisphere Latina/o (traditionally, people of Latin national economies, creating systems of and to countries in Europe and Asia—at American and Caribbean origin in the socioeconomic interdependence. -

Landscaping Hispaniola Moreau De Saint-Méry's

New West Indian Guide Vol. 85, no. 3-4 (2011), pp. 169-190 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/index URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101703 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0028-9930 MARIA CRISTINA FUMAGALLI LANDSCAPING HISPANIOLA MOREAU DE SAINT-MÉRY’S BORDER POLITICS A few days after the Haitian earthquake of January 12, 2010, Sonia Marmolejos, a young Dominican woman who was in the Darío Contreras Hospital of Santo Domingo with her newborn daughter, decided to breastfeed three Haitian children who had been admitted there after the disaster. They were wounded, hungry, and dehydrated, so Sonia Marmolejos acted on impulse and she did not expect to receive any special recognition for her generous gesture. The government of the Dominican Republic capitalized on this story, defined Sonia Marmolejos as a heroine, and used her actions as a metaphor to illustrate the charitable response of the country toward neighboring Haiti. Haiti and the Dominican Republic share the island of Hispaniola and a history of colonialism which, however, has conjugated itself in very differ- ent ways. Officially under Spanish rule since 1493, the island was mostly left unpopulated for three-quarters of a century. In 1625 the French started to occupy parts of it (mainly in the north) and until the official recognition of the French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1777, they constantly pushed for- ward their unofficial borders, while the Spanish carried out punitive raids to eradicate the French presence. On the Spanish side, the economy was mainly livestock-based but the French developed an impressive network of planta- tions which relied on the constant import of enslaved labor from Africa. -

The Meanings of Marimba Music in Rural Guatemala

The Meanings of Marimba Music in Rural Guatemala Sergio J. Navarrete Pellicer Ph D Thesis in Social Anthropology University College London University of London October 1999 ProQuest Number: U643819 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643819 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis investigates the social and ideological process of the marimba musical tradition in rural Guatemalan society. A basic assumption of the thesis is that “making music” and “talking about music” are forms of communication whose meanings arise from the social and cultural context in which they occur. From this point of view the main aim of this investigation is the analysis of the roles played by music within society and the construction of its significance as part of the social and cultural process of adaptation, continuity and change of Achi society. For instance the thesis elucidates how the dynamic of continuity and change affects the transmission of a musical tradition. The influence of the radio and its popular music on the teaching methods, music genres and styles of marimba music is part of a changing Indian society nevertheless it remains an important symbols of locality and ethnic identity. -

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

Description of Some Basic Moves of Salsa Casino Rueda Style a Cruz’: Description If Basic Arm Positions in Salsa Rueda

www.SalsaGente.com The Moves ! Thank you for choosing “Salsa Gente” as source for your information! We are community oriented and based in Santa Cruz and maintain Cuban-style Salsa dance since 2001. We offer classes and dance opportunities filled with lots of fun. As courtesy, we describe some basic Salsa Rueda de Casino moves starting with Beginner level and list our Salsa Rueda Curriculum of classes. The curriculum may differ from other Salsa Rueda organizations or Website listings. Description of some Basic Moves of Salsa Casino Rueda style a Cruz’: Description if Basic Arm Positions in Salsa Rueda Name of Position Description guapea position/parallel (Left to Right) and (Right to Left). Leader is on the Right side of Follower. arms Leader and Follower face each other holding hands around waist level. Leader is on the Left side of Follower. Leader and Follower face each other. Leader has Right Hand behind the back of Follower, Follower’s Left Hand is pa'l medio position on the Right shoulder of Leader. Leader is holding Right Hand of Follower with elbows bent upward. Palms and elbows are touching. Make an "L" shape with your arms. cross handed Couples face each other, arms crossed with Right hands on top. Couples are side to side and Leader is to the Left of Follower. Leader has Left Sombrero arms Hand behind own head holding Left Hand of Follower. Leader also has Right Hand behind the head of Follower holding Right Hand of Follower. Leader's elbow comes up and over the upper arm of the Follower. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Sociolinguistic Integration of to Approaches Migration Andthe Sociolinguistic Methodological Theoretical

Theoretical Methodological and the Sociolinguistic Migration Approaches to of Integration Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Sociolinguistic • Florentino Paredes García and María Sancho Pascual Integration of Migration Edited by Florentino Paredes García and María Sancho Pascual Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Languages www.mdpi.com/journal/languages Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Sociolinguistic Integration of Migration Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Sociolinguistic Integration of Migration Special Issue Editors Florentino Paredes Garc´ıa Mar´ıa Sancho Pascual MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Special Issue Editors Florentino Paredes Garc´ıa Mar´ıa Sancho Pascual University of Alcala´ Complutense University of Madrid Spain Spain Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Languages (ISSN 2226-471X) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/languages/special issues/sociolinguistic migration). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03936-192-2 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03936-193-9 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Florentino Paredes Garc´ıa and Mar´ıa Sancho Pascual. c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IN EL NORTE CON CALLE 13 AND TEGO CALDERÓN: TRACING AN ARTICULATION OF LATINO IDENTITY IN REGUETÓN By CYNTHIA MENDOZA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Cynthia Mendoza 2 To Emilio Aguirre, de quien herede el amor a los libros To Mami and Sis, for your patience in loving me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank G, for carrying me through my years of school. I thank my mother, Rosalpina Aguirre, for always being my biggest supporter even when not understanding. I thank my sister, Shirley Mendoza-Castilla, for letting me know when I am being a drama queen, providing comedic relief in my life, and for being a one-of-a-kind sister. I thank my aunt Lucrecia Aguirre, for worrying about me and calling to yell at me. I thank my Gainesville family: Priscilla, Andres, Ximena, and Cindy, for providing support and comfort but also the necessary breaks from school. I want to thank Rodney for being just one phone call away. I thank my committee: Dr. Horton-Stallings and Dr. Marsha Bryant, for their support and encouragement since my undergraduate years; without their guidance, I cannot imagine making it this far. I thank Dr. Efraín Barradas, for his support and guidance in understanding and clarifying my thesis subject. I thank my cousins Katia and Ana Gabriela, for reminding why is it that I do what I do. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 -

Microsoft Office Outlook

Polinsky, Daniel From: Carolina Perrina [[email protected]] Sent: Monday, May 24, 2010 2:44 PM To: Undisclosed recipients Subject: MARLINS FACE OFF AGAINST THE BRAVES, PHILLIES, BREWERS For Immediate Release Carolina Perrina May 24, 2010 (305) 626- 7389 [email protected] MARLINS FACE OFF AGAINST THE BRAVES, PHILLIES, BREWERS Homestand to Feature Salsa Sensations Jerry Rivera and Luis Enrique as part of Super Saturday Concert Series MIAMI –The Florida Marlins are set to host the Atlanta Braves (May 25-27), the Philadelphia Phillies (May 28-30) and the Milwaukee Brewers (May 31-June 3) at Sun Life Stadium. The ten-game homestand will feature fan giveaways, including: Cody Ross Bobblehead courtesy of GEICO as part of Billy Bingo (May 28), Marlins Tambourine sponsored by Majestic Athletic (May 29) and Dan Uggla Poster sponsored by City Furniture (May 30). The homestand will also feature several special events, including: Jiffy Lube Fiesta Friday on May 28, Baker Concrete Super Saturday featuring salsa sensations Jerry Rivera and Luis Enrique on May 29, and Marlins Family Sunday on May 30. Starting Tuesday, May 25, the Marlins kick off the homestand against the Atlanta Braves. First pitch is set for 7:10 P.M. at Sun Life Stadium. Fans can look in the Tuesday edition of The Miami Herald for the Herald Two for Tuesday coupon and get two-for-one Bullpen Box tickets. The series continues on Wednesday where fans can take advantage of the Marlins $7.90 The Ticket Infield Box Blowout Promotion. The series against the Braves will conclude on Thursday, May 27. -

![[Thesis Title]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1858/thesis-title-561858.webp)

[Thesis Title]

¡SI TE ATREVES! COMPOSING MUSIC AND BLACK IDENTITY IN PERU, 1958-1974 Andrew A. Reinel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 30, 2008 Advised by Professors: Jesse Hofnung-Garskof & Paulina Alberto For Mom, Dad, Lucy, Maria, and Dianne (familia). TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures .............................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ iii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Nicomedes Santa Cruz .......................................................................... 10 Chapter Two: Victoria Santa Cruz .............................................................................. 23 Chapter Three: Peru Negro .......................................................................................... 33 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 42 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 46 FIGURES Figure 1. “Cumanana” 3rd Ed. (1970)……………………………………………………18 Figure 2. “…Con Victoria Santa Cruz” (1972)………………………………………….26 Figure 3. “Peru Negro” (1974)………………………………………………...................39 -

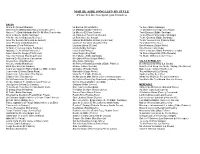

MAR DE ASHÉ SONG LIST- by STYLE (Please Feel Free to Request Your Favorites)

MAR DE ASHÉ SONG LIST- BY STYLE (Please feel free to request your favorites) SALSA Ahora Sí (Ismael Miranda) La Bomba (Ricky Martin) Te Amo (Eddie Santiago) Alabanciosa (Manny Oquendo y Conjunto Libre) La Malanga (Eddie Palmieri) Te Quedarás Conmigo (Tito Rojas) Alguien Te Está Hablando Mal De Mi (Ray Sepulveda) La Muerte (El Gran Combo) Todo Empezó (Eddie Santiago) Amar A Muerte (Eddie Santiago) La Paila (Los Hermanos Moreno) Tu Me Haces Falta (Eddie Santiago) A Mi Me Huele (Orquesta Mulenze) La Rebelión (Joe Arroyo) Tu Me Quemas (Eddie Santiago) Amor De Secreto (Orquesta de La Luz) Latinos En Estados Unidos (Celia Cruz) Tu Me Vuelves Loco (Frankie Ruiz) Amor Por Ella (Andy Montañez) Llanto de Cocodrilo (Ray Barretto) Toro Mata (Celia Cruz) Anacaona (Cheo Feliciano) Llorarás (Oscar D’Leon) Una Aventura (Grupo Niche) Antidoto Y Veneno (Eddie Santiago) Lluvia (Eddie Santiago) Uno Mismo (Tony Vega) Apiádate De Mi (Victor Manuelle) Lucía (Luis Enrique) Vivir Lo Nuestro (Marc Anthony y La India) Aquel Amor De Fuego (Tito Nieves) Luna Negra (Rey Ruiz) Ya No Lo Hago Más (Willie Rosario) Aquellos Tiempos (Ray Sepulveda) Me Fallaste (Eddie Santiago) Yo No Se Mañana (Luis Enrique) Arranca En Fa (Sonora Carruseles) Me Sabe A Peru (Grupo Niche) Arrepiéntete (Ray Barretto) Mía (Eddie Santiago) SALSA IN ENGLISH Ay Cucu (Andy Montañez) Mi Primera Rumba (La India y Eddie Palmieri) Betcha By Golly Wow (La Sirena) Baila Que Baila (El Canario) Mírame (Jaime Roviras) How Do You Keep The Music Playing (Tito Nieves) Como Un Huracán (Rubén Blades y Willie