Arxiv:1704.03416V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 11 Apr 2017 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group Problems #22 - Solutions

Group Problems #22 - Solutions Friday, October 21 Problem 1 Ritz Combination Principle Show that the longest wavelength of the Balmer series and the longest two wavelengths of the Lyman series satisfy the Ritz Combination Principle. The wavelengths corresponding to transitions between two energy levels in hydrogen is given by: n2 λ = λlimit 2 2 ; (1) n − n0 where n0 = 1 for the Lyman series, n0 = 2 for the Balmer series, and λlimit = 91:1 nm for the Lyman series and λlimit = 364:5 nm for the Balmer series. Inspection of this equation shows that the longest wavelength corresponds to the transition between n = n0 and n = n0 + 1. Thus, for the Lyman series, the longest two wavelengths are λ12 and λ13. For the Balmer series, the longest wavelength is λ23. The Ritz combination principle states that certain pairs of observed frequencies from the hydrogen spectrum add together to give other observed frequencies. For this particular problem, we then have: ν12 + ν23 = ν13 =) h(ν12 + ν23) = hν13 (2) 1 1 1 =) hc + = hc (3) λ12 λ23 λ13 1 1 1 =) + = : (4) λ12 λ23 λ13 Inverting Eqn. 1 above gives: 2 2 2 1 1 n − n0 1 n0 = 2 = 1 − 2 : (5) λ λlimit n λlimit n To calculate 1/λ12 and 1/λ13, we use the Lyman series numbers and find 1/λ12 = −1 −1 3=(4 ∗ 91:1) = 0:00823 nm and 1/λ13 = 8=(9 ∗ 91:1) = 0:00976 nm . To compute 1/λ23, we use the Balmer series numbers and find 1/λ23 = 5=(9 ∗ 364:5) = 0:00152 −1 nm . -

Observations of the Lyman Series Forest Towards the Redshift 7.1 Quasar ULAS J1120+0641 R

A&A 601, A16 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630258 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Observations of the Lyman series forest towards the redshift 7.1 quasar ULAS J1120+0641 R. Barnett1, S. J. Warren1, G. D. Becker2, D. J. Mortlock1; 3; 4, P. C. Hewett5, R. G. McMahon5; 6, C. Simpson7, and B. P. Venemans8 1 Astrophysics Group, Blackett Laboratory, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Avenue, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 3 Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK 4 Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, Albanova, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 5 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 6 Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 7 Gemini Observatory, Northern Operations Center, N. A’ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA 8 Max-Planck Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany Received 15 December 2016 / Accepted 9 February 2017 ABSTRACT We present a 30 h integration Very Large Telescope X-shooter spectrum of the Lyman series forest towards the z = 7:084 quasar ULAS J1120+0641. The only detected transmission at S=N > 5 is confined to seven narrow spikes in the Lyα forest, over the redshift range 5:858 < z < 6:122, just longward of the wavelength of the onset of the Lyβ forest. There is also a possible detection of one further unresolved spike in the Lyβ forest at z = 6:854, with S=N = 4:5. -

Unique Astrophysics in the Lyman Ultraviolet

Unique Astrophysics in the Lyman Ultraviolet Jason Tumlinson1, Alessandra Aloisi1, Gerard Kriss1, Kevin France2, Stephan McCandliss3, Ken Sembach1, Andrew Fox1, Todd Tripp4, Edward Jenkins5, Matthew Beasley2, Charles Danforth2, Michael Shull2, John Stocke2, Nicolas Lehner6, Christopher Howk6, Cynthia Froning2, James Green2, Cristina Oliveira1, Alex Fullerton1, Bill Blair3, Jeff Kruk7, George Sonneborn7, Steven Penton1, Bart Wakker8, Xavier Prochaska9, John Vallerga10, Paul Scowen11 Summary: There is unique and groundbreaking science to be done with a new generation of UV spectrographs that cover wavelengths in the “Lyman Ultraviolet” (LUV; 912 - 1216 Å). There is no astrophysical basis for truncating spectroscopic wavelength coverage anywhere between the atmospheric cutoff (3100 Å) and the Lyman limit (912 Å); the usual reasons this happens are all technical. The unique science available in the LUV includes critical problems in astrophysics ranging from the habitability of exoplanets to the reionization of the IGM. Crucially, the local Universe (z ≲ 0.1) is entirely closed to many key physical diagnostics without access to the LUV. These compelling scientific problems require overcoming these technical barriers so that future UV spectrographs can extend coverage to the Lyman limit at 912 Å. The bifurcated history of the Space UV: Much the course of space astrophysics can be traced to the optical properties of ozone (O3) and magnesium fluoride (MgF2). The first causes the space UV, and the second divides the “HST UV” (1150 - 3100 Å) and the “FUSE UV” (900 - 1200 Å). This short paper argues that some critical problems in astrophysics are best solved by a future generation of high-resolution UV spectrographs that observe all wavelengths between the Lyman limit and the atmospheric cutoff. -

Balmer and Rydberg Equations for Hydrogen Spectra Revisited

1 Balmer and Rydberg Equations for Hydrogen Spectra Revisited Raji Heyrovska Institute of Biophysics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 135 Kralovopolska, 612 65 Brno, Czech Republic. Email: [email protected] Abstract Balmer equation for the atomic spectral lines was generalized by Rydberg. Here it is shown that 1) while Bohr's theory explains the Rydberg constant in terms of the ground state energy of the hydrogen atom, quantizing the angular momentum does not explain the Rydberg equation, 2) on reformulating Rydberg's equation, the principal quantum numbers are found to correspond to integral numbers of de Broglie waves and 3) the ground state energy of hydrogen is electromagnetic like that of photons and the frequency of the emitted or absorbed light is the difference in the frequencies of the electromagnetic energy levels. Subject terms: Chemical physics, Atomic physics, Physical chemistry, Astrophysics 2 An introduction to the development of the theory of atomic spectra can be found in [1, 2]. This article is divided into several sections and starts with section 1 on Balmer's equation for the observed spectral lines of hydrogen. 1. Balmer's equation Balmer's equation [1, 2] for the observed emitted (or absorbed) wavelengths (λ) of the spectral lines of hydrogen is given by, 2 2 2 λ = h B,n1[n2 /(n2 - n 1 )] (1) 2 where n1 and n2 (> n1) are integers with n1 having a constant value, hB,n1 = n1 hB is a constant for each series and hB is a constant. For the Lyman, Balmer, Paschen, Bracket and Pfund series, n1 = 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 respectively. -

Spectra of Photoionized Regions 1. Introduction

Spectra of Photoionized Regions Friday, January 21, 2011 CONTENTS: 1. Introduction 2. Recombination Processes A. Overview B. Level networks C. Free-bound continuum D. Two-photon continuum E. Collisions 3. Additional Processes A. Lyman-α emission B. Helium processes C. Resonance fluorescence 4. Diagnostics A. Temperature B. Density C. Composition D. Star formation rates 1. Introduction Our next task is to consider the emitted spectrum from an H II region. This is one of the most important subjects observationally since spectroscopy provides our principal set of diagnostics on the physics occurring in the region. This material is (mostly) covered in Chapters 4 and 5 of Osterbrock & Ferland (on which most of these notes are based). The sources of emission we will consider fall into two categories: Cooling: Infrared fine structure lines Optical forbidden lines Free-free continuum Recombination: Free-bound continuum Recombination lines Two-photon continuua 1 Generally, the forbidden lines (optical or IR) come from metals, whereas the recombination features are proportional to abundance and arise mainly from H and He. Since the cooling radiation has already been discussed, we will focus on recombination and then proceed to diagnostics. 2. Recombination Processes A. OVERVIEW We first consider the case of recombination of hydrogen at very low densities where the collision rates are small, i.e. any hydrogen atom that forms can decay radiatively before any collision. Later on we will introduce collisions between particles (electrons, protons) with excited atoms. The recombination process at low density begins with a radiative recombination, H+ + e− → H0(nl) + γ , which populates an excited state of the hydrogen atom. -

The Hydrogen Atom and the Lyman Series Block: ______Answer Each Question in the Space Required

Chemistry Worksheet NAME: _____________________________ The Hydrogen Atom and the Lyman series Block: _________ Answer each question in the space required. Show all work. Pay attention to significant figures and units. 1. Hydrogen is the simplest atom in the universe, thus it is the most commonly used example for delving into the quantum world. The energy levels of hydrogen can be calculated using the 2 principle quantum number, n, in the equation En = −13.6 eV (1/n ), for n = 1, 2, 3, 4 … ∞. Recall that eV stands for the energy unit called the electron volt, which relates to joules (J) by the following conversion: 1 eV = 1.602 × 10−19 J. a. What is the value of principal quantum number, n, for the ground state of hydrogen? b. Calculate the energy (in eV and in joules) for the ground state of hydrogen. c. Calculate the energy, En, for the first four excited states of the hydrogen atom. d. Is the third excited state higher or lower in energy than the ground state? Justify your answer in one or two sentences. e. The ionization energy of hydrogen is defined as the minimum energy required to excite an electron from the ground state to a state where the electron is separated from the nucleus (the proton). From your answers above, what is the ionization energy for hydrogen? Justify your answer in one or two sentences. f. How much energy would be required to ionize an entire mole of hydrogen atoms? Copyright© 2007, Alan D. Crosby, Newton South High School, Newton, MA 02459 Chemistry Worksheet NAME: _____________________________ The Hydrogen Atom and the Lyman series Block: _________ 2. -

Atomic Structure

1 Atomic Structure 1 2 Atomic structure 1-1 Source 1-1 The experimental arrangement for Ruther- ford's measurement of the scattering of α particles by very thin gold foils. The source of the α particles was radioactive radium, a rays encased in a lead block that protects the surroundings from radiation and confines the α particles to a beam. The gold foil used was about 6 × 10-5 cm thick. Most of the α particles passed through the gold leaf with little or no deflection, a. A few were deflected at wide angles, b, and occasionally a particle rebounded from the foil, c, and was Gold detected by a screen or counter placed on leaf Screen the same side of the foil as the source. The concept that molecules consist of atoms bonded together in definite patterns was well established by 1860. shortly thereafter, the recognition that the bonding properties of the elements are periodic led to widespread speculation concerning the internal structure of atoms themselves. The first real break- through in the formulation of atomic structural models followed the discovery, about 1900, that atoms contain electrically charged particles—negative electrons and positive protons. From charge-to-mass ratio measurements J. J. Thomson realized that most of the mass of the atom could be accounted for by the positive (proton) portion. He proposed a jellylike atom with the small, negative electrons imbedded in the relatively large proton mass. But in 1906-1909, a series of experiments directed by Ernest Rutherford, a New Zealand physicist working in Manchester, England, provided an entirely different picture of the atom. -

Hydrogen Atom – Lyman Series Rydberg’S Formula Hydrogen 91.19Nm Energy Λ = Levels 1 1 0Ev − M2 N2

Hydrogen atom – Lyman Series Rydberg’s formula Hydrogen 91.19nm energy λ = levels 1 1 0eV − m2 n2 Predicts λ of nàm transition: Can Rydberg’s formula tell us what ground n (n>m) state energy is? m (m=1,2,3..) -?? eV m=1 Balmer-Rydberg formula Hydrogen energy levels 91.19nm 0eV λ = 1 1 − m2 n2 Look at energy for a transition between n=infinity and m=1 1 0 ≡ 0eV hc hc ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ Einitial − E final = = ⎜ 2 − 2 ⎟ λ 91.19nm ⎝ m n ⎠ -?? eV hc − E final = E 13.6eV 91.19nm 1 = − Hydrogen energy levels A more general case: What is 0eV the energy of each level (‘m’) in hydrogen? … 0 ≡ 0eV hc hc ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ Einitial − E final = = ⎜ 2 − 2 ⎟ λ 91.19nm ⎝ m n ⎠ -?? eV hc 1 1 − E = E = −13.6eV final 91.19nm m2 m m2 Balmer/Rydberg had a mathematical formula to describe hydrogen spectrum, but no mechanism for why it worked! Why does it work? Hydrogen energy levels 410.3 486.1Balmer’s formula656.3 nm 434.0 91.19nm λ = 1 1 − m2 n2 where m=1,2,3 and where n = m+1, m+2 The Balmer/Rydberg formula correctly describes the hydrogen spectrum! Is it a good model? The Balmer/Rydberg formula is a mathematical representation of an empirical observation. It doesn’t really explain anything. How can we explain (not only calculate) the energy levels in the hydrogen atom? Next step: A semi-classical explanation of the atomic spectra (Bohr model) Rutherford shot alpha particles at atoms and he figured out that a tiny, positive, hard core is surrounded by negative charge very far away from the core. -

The Structure of Hydrogen

Chapter 9 The structure of hydrogen One of the many goals of the astronomical spectroscopist is to interpret the details of spectral features in order to deduce the properties of the radiating or absorbing matter. In Chapters 4 and 5, we introduced much of the for- malism connecting the atomic absorption features observed in spectra with the all–important atomic absorption coefficient, α(λ). The mathematical form of absorption coefficients are derived directly from the theoretical model of the atom. As such, it is essential to understand the internal working nature of the atom in order to deduce the physical conditions of the matter giving rise to observed spectral features. The model of the atom is simple in principle, yet highly complex in de- tail. Employing only first–order physics, we have been extremely successful at formulating the basic atomic model, including the internal energy structure, transition probabilities, and the spectra of the various atoms and ions. How- ever, first–order physics is not complete enough to precisely describe the internal energy structure of the atom nor the observed spectral features. Enter the com- plexity of higher–order physics, which are most easily discussed in terms of small corrections to the first–order model. The simplest atom is hydrogen, which comprises a single proton for the nucleus and a single orbiting electron. The complexity of the physics increases as the number of nuclear protons and orbiting electrons increases. The hydrogen atom serves to clearly illustrate the effects of higher–order corrections while avoiding the complication of multiple interacting electrons. In this chapter, we focus on the first–order physics, internal energy structure, and resulting spectrum of neutral hydrogen and hydrogen–like ions (those with a single orbiting electron). -

Lyman Alpha Forest Michael Rauch

eaa.iop.org DOI: 10.1888/0333750888/2140 Lyman Alpha Forest Michael Rauch From Encyclopedia of Astronomy & Astrophysics P. Murdin © IOP Publishing Ltd 2006 ISBN: 0333750888 Institute of Physics Publishing Bristol and Philadelphia Downloaded on Thu Mar 02 23:49:43 GMT 2006 [131.215.103.76] Terms and Conditions Lyman Alpha Forest E NCYCLOPEDIA OF A STRONOMY AND A STROPHYSICS Lyman Alpha Forest Lyα forest systems in this restricted definition, but we have theoretical reasons to believe that there is a genuine The Lyman alpha forest is an absorption phenomenon seen dichotomy between intergalactic gas (represented by the in the spectra of high redshift QSOs and galaxies (figure Lyα forest), even if partly polluted by metals, and the 1). It is the only direct observational evidence we have of invariably metal-enriched higher column density systems, the existence and properties of the general INTERGALACTIC thought to be related to galaxies. MEDIUM, and, as we have reason to believe, of most of the Lyα forest absorption systems have now been baryonic matter contents of the universe. observed from REDSHIFT zero (with UV satellites) up to the On its way to us the light of a bright, distant highest redshifts at which background light sources (QSOs QSO passes through intervening intergalactic gas and and galaxies) can still be found (currently z ∼ 5–6). through gas clouds associated with foreground galaxies. Absorption by the gas modifies the spectra of the The Gunn–Peterson effect: where does the background objects and imprints a record of the gas absorption come from? α clouds’ physical and chemical states on the observed Ly forest absorption in a QSO spectrum was predicted background QSO and galaxy spectra. -

First Detection of Lyman Continuum Escape from a Local Starburst Galaxy

A&A 448, 513–524 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20053788 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics First detection of Lyman continuum escape from a local starburst galaxy I. Observations of the luminous blue compact galaxy Haro 11 with the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE) N. Bergvall1, E. Zackrisson1, B.-G. Andersson2, D. Arnberg1,J.Masegosa3, and G. Östlin4 1 Dept. of Astronomy and Space Physics, Box 515, 75120 Uppsala, Sweden e-mail: [nils.bergvall;erik.zackrisson]@astro.uu.se 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA e-mail: [email protected] 3 Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia, Granada, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 4 Stockholm Observatory, SCFAB, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] Received 7 July 2005 / Accepted 2 November 2005 ABSTRACT Context. The dominating reionization source in the young universe has not yet been identified. Possible candidates include metal poor dwarf galaxies with starburst properties. Aims. We selected an extreme starburst dwarf, the Blue Compact Galaxy Haro 11, with the aim of determining the Lyman continuum escape fraction from UV spectroscopy. Methods. Spectra of Haro 11 were obtained with the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE). A weak signal shortwards of the Lyman break is identified as Lyman continuum (LyC) emission escaping from the ongoing starburst. From profile fitting to weak metal lines we derive column densities of the low ionization species. Adopting a metallicity typical of the H II regions of Haro 11, these data correspond to a hydrogen column density of ∼1019cm−2. -

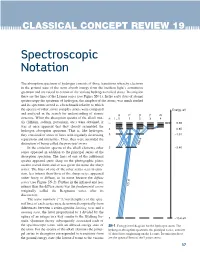

Spectroscopic Notation

CLASSICAL CONCEPT REVIEW 19 Spectroscopic Notation The absorption spectrum of hydrogen consists of those transitions whereby electrons in the ground state of the atom absorb energy from the incident light’s continuous spectrum and are raised to certain of the various hydrogen excited states. In emission these are the lines of the Lyman series (see Figure SN-1). In the early days of atomic spectroscopy the spectrum of hydrogen, the simplest of the atoms, was much studied and its spectrum served as a benchmark relative to which the spectra of other, more complex atoms were compared Energy, eV and analyzed in the search for understanding of atomic S P D F G structure. When the absorption spectra of the alkali met- n l = 0 1 2 3 4 als (lithium, sodium, potassium, etc.) were obtained, it ∞ 0.00 was at once apparent that they closely resembled the hydrogen absorption spectrum. That is, like hydrogen, 4 –0.85 they consisted of series of lines with regularly decreasing 3 –1.51 separations and intensities. Thus, they were accorded the distinction of being called the principal series. 656.3 In the emission spectra of the alkali elements other 2 –3.40 series appeared in addition to the principal series of the absorption spectrum. The lines of one of the additional spectra appeared quite sharp on the photographic plates used to record them and so was given the name the sharp series. The lines of one of the other series seen in emis- sion, less intense than those of the sharp series, appeared rather fuzzy or diffuse, so its name became the diffuse series (see Figure SN-2).