Multiple Reflections of an Urban Marae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of the Treaty Part 1 (Pdf

THE STORY OF THE TREATY Introduction This is the story of our founding document, the Treaty agreement contained within it. At the outset it of Waitangi. It tells of the events leading up to the should be noted that, while the steps leading to the Treaty at a time when Mäori, far outnumbering Treaty are well known and have been thoroughly Päkehä, controlled New Zealand. It describes the studied, historians do differ in what they see as the The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. Over 500 Mäori chiefs and essential bargain that was struck between Mäori main developments and trends. Some historians, for representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty in 1840. Like all treaties it is an exchange and the British Crown and what both sides hoped example, emphasise the humanitarian beliefs of the of promises; the promises that were exchanged in 1840 were the basis on which the British to obtain by agreeing to it. However, it does not tell 1830s; others draw attention to the more coercive Crown acquired New Zealand. The Treaty of Waitangi agreed the terms on which New Zealand the full story of what has happened since the signing aspects of British policy or take a middle course would become a British colony. of the Treaty in 1840: of the pain and loss suffered of arguing that while British governments were by Mäori when the Treaty came to be ignored concerned about Mäori, they were equally concerned This is one of a series of booklets on the Treaty of Waitangi which are drawn from the Treaty of by successive settler-dominated governments in about protecting the interests of Britain and British Waitangi Information Programme’s website www.treatyofwaitangi.govt.nz. -

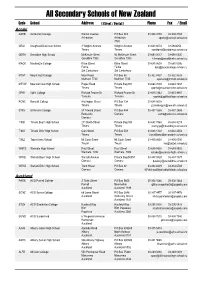

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Stories from Te Wharenui Teaching Resource ‘Identity’

Stories from Te Wharenui Teaching Resource ‘Identity’ OVERVIEW This unit explores the importance of oral and visual storytelling in Māori culture to show identity and record the history of people and events over time. Learning Outcomes Students will: ● Identify the purpose, context and materials of traditional Māori taonga seen in wharenui ● Identify key patterns and symbols found in whakairo, kōwhaiwhai and tukutuku ● Share their own stories of who they are or retell traditional stories using a range of ways Contents 1 – WHARENUI (Carved Meeting House) Wharenui represent the ancestors and are made up of many parts to symbolise the human form. Many contain carvings and panels that show whakapapa (genealogy) of the iwi (tribe) and stories of the people and land. 2 – WHAKAIRO (Carvings) Māori did not have a written history in the form of an alphabet, but the carvings themselves are recorded history that people could read; the shape of the head, position of body and surface patterns combine to tell stories. 3 - TUKUTUKU Tukutuku are the woven harakeke (flax) panels that adorn wharenui and are placed between poupou. Their purpose is to tell stories of life to complement the poupou on each side. Explore their symbolism. 4 – KŌWHAIWHAI Kōwhaiwhai patterns are found on the rafters of the wharenui and as well as being decorative, they are used for enhancing stories. Nature is often the inspiration for these beautiful patterns. Curriculum Links Social Science: English: ▪ Place and Environment ▪ Making meaning ▪ Continuity and Change ▪ Creating meaning The Arts: Digital Technology: ▪ Understanding the Arts in Context ▪ Designing and Developing Digital Outcomes ▪ Developing Ideas ▪ Computational Thinking ▪ Communicating and Interpreting Mathematics and Statistics: Te Reo Māori - Te Whakatōtanga 1: ▪ Geometry and Measurement ▪ Kōrero - speaking Technology: ▪ Mātakitaki – viewing ▪ Technological practice ▪ Whakaatu – presenting ▪ Nature of technology Identity Resource by Imogen Rider is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License. -

The Whare-Oohia: Traditional Maori Education for a Contemporary World

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WHARE-OOHIA: TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY WORLD A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education at Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand Na Taiarahia Melbourne 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS He Mihi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 The Research Question…………………………………….. 5 1.2 The Thesis Structure……………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 2: HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 9 2.1 The Origins of Traditional Maaori Education…………….. 9 2.2 The Whare as an Educational Institute……………………. 10 2.3 Education as a Purposeful Engagement…………………… 13 2.4 Whakapapa (Genealogy) in Education…………………….. 14 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW 16 3.1 Western Authors: Percy Smith;...……………………………………………… 16 Elsdon Best;..……………………………………………… 22 Bronwyn Elsmore; ……………………………………….. 24 3.2 Maaori Authors: Pei Te Hurinui Jones;..…………………………………….. 25 Samuel Robinson…………………………………………... 30 CHAPTER 4: RESEARCHING TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 33 4.1 Cultural Safety…………………………………………….. 33 4.2 Maaori Research Frameworks…………………………….. 35 4.3 The Research Process……………………………………… 38 CHAPTER 5: KURA - AN ANCIENT SCHOOL OF MAAORI EDUCATION 42 5.1 The Education of Te Kura-i-awaawa;……………………… 43 Whatumanawa - Of Enlightenment..……………………… 46 5.2 Rangi, Papa and their Children, the Atua:…………………. 48 Nga Atua Taane - The Male Atua…………………………. 49 Nga Atua Waahine - The Female Atua…………………….. 52 5.3 Pedagogy of Te Kura-i-awaawa…………………………… 53 CHAPTER 6: TE WHARE-WAANANGA - OF PHILOSOPHICAL EDUCATION 55 6.1 Whare-maire of Tuhoe, and Tupapakurau: Tupapakurau;...……………………………………………. -

Processes of Pakeha Change in Response To

http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. PROCESSES OF PAKEHA CHANGE IN RESPONSE TO THE TREATY OF WAITANGI A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Waikato by Ingrid Huygens 2007 DEDICATION To my father the labourer‐philosopher who pondered these things as he drove his tractor i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My most respectful and loving acknowledgments to my peer study group of Mitzi and Ray Nairn, Rose Black and Tim McCreanor. Their combined experience spanned a depth and breadth of Pakeha Treaty work that framed my research project. Their academic, emotional and practical support during times of ill-health and scant resources made this thesis possible. To my colleagues, the Treaty and decolonisation educators who shared with me their reflections, their dreams and their ways of working. It was a privilege to visit each group in their home area, and my year of travelling around the country will always stand out as one of warmth, colour and generosity. -

AFF / NFF Idme Ground Codes Northland

AFF / NFF iDMe Ground Codes Northland DGCUL McKay Stadium Office (NFF) IGUFE Ruakaka UGQSQ Awanui Sports Complex MVPEW Ruawai College WDHHV Bay of Islands College PXUGO Russell Primary School FKJNO Bay of Islands International Academy FYVDL Russell Sports Ground KIPEO Baysport Waipapa EFIXD Semenoff Stadium HHHKU Bledisloe Domain GGPPR Taipa School ERHSY Bream Bay College ECNNG Tarewa Park JWFFS Dargaville High School JYRVA Tauraroa Area School TUILP Huanui College OKGJA Tikipunga High School PNJUW Hurupaki School XLYCV Tikipunga Park MYCUE Kaitaia College FQFLT Wentworth College EDDPP Kamo High School GFREY Whangarei Boys High School KAQYF Kamo Sports Park HCWJP Whangarei Events Centre VJXGP Kensington Park OXMXD Whangarei Girls High School PMYOV Kerikeri Domain AJBAU Whangarei Heads School HJLJR Kerikeri High School LONEC Whangaroa College TPSGS Kerikeri Primary School ORKEG William Fraser Park OQVUW Koropupu Sports Park YDFDF Lindvart Park SLRHR Mangakahia Sports Complex 1 CMLAN Mangawhai Beach School THSQQ Mangawhai Domain YTMYF Maunu School DCSID Memorial Park (Dargaville) HWBQQ Moerewa School GHNSJ Morningside Park KBAHC Ngunguru Sports Complex JQPCR Northland College IFAWA Ohaeawai Primary School FQRIG Okaihau College RMTIB Okaihau Primary School YNQBF Omapare School VMEXN Onerahi Airport IQRIR Opononi Area School YBNXY Oromahoe Primary School FYMAM Otaika Domain AYIUU Otamatea High School MUQPV Parua Bay School SIERO Pompallier College JYTGB Puriri Park Reserve ELXMD Riverview Primary School North Harbour / Waitakere GNOFF North -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

NCEA How Your School Rates: Auckland

NCEA How your school rates: Auckland Some schools oer other programmes such as Level 1 Year 11 NA Results not available L1 International Baccalaureate and Cambridge Exams L2 Level 2 Year 12 L3 Level 3 Year 13 point increase or decrease since 2012 UE University Entrance % of students who passed in 2013 % Decile L1 L2 L3 UE Al-Madinah School 2 84.6 -15.4 95.6 -4.4 100 0 93.3 -0.8 Albany Senior High School 10 90.7 5.3 91.7 3.2 91 11 84.1 14.5 Alfriston College 3 75.4 9 70.3 -5.1 66 -0.1 46.9 5.4 Aorere College 2 58.8 0.3 75.3 5.8 68.8 9.8 57.7 13.7 Auckland Girls’ Grammar School 5 80 5.7 81.5 3.9 68.2 -10.6 61.3 -12.4 Auckland Grammar School 10 46.1 37.8 79 2.1 66.4 1.4 54.9 -15.7 Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist High School 2 54.1 -3 45.6 -42.9 73 3.6 57.6 7.6 Avondale College 4 78.8 3.7 87.5 6.7 79.9 8.3 78.9 12.3 Baradene College of the Sacred Heart 9 98.7 5.2 100 0 97.8 4 96.3 4 Birkenhead College 6 80.5 4.4 80.1 -12.8 73.3 0.3 62 -2 Botany Downs Secondary College 10 90.6 -0.4 91.8 -0.1 88.3 8 84.8 6.9 Carmel College 10 97.4 -1.2 99.2 2 97 2.7 93.4 4.7 De La Salle College 1 79.7 9.5 75.1 5.5 59.1 -5.1 54.8 15.6 Dilworth School 4 81.7 -0.3 88.3 4.3 77.9 -7.1 71.1 -7.2 Diocesan School for Girls 10 98.3 0.2 96.6 -2.7 96.4 3.3 96.4 2.5 Edgewater College 4 89.5 8 80.6 -3.7 73.2 10.4 51.7 3.4 Elim Christian College 8 93.3 15.1 88.8 5.8 86.9 -3.2 91.3 5.1 Epsom Girls’ Grammar School 9 92.3 0.7 94.5 2.8 86.7 2.4 89.2 4.9 Glendowie College 9 90 -2.5 91.1 0.8 82.4 -3.8 81.8 1.5 Gleneld College 7 67.2 -9.3 78.6 5.4 72.5 -6.9 63.2 0.5 Green Bay High -

Copyright Is Owned by the Author of the Thesis. Permission Is Given for a Copy to Be Downloaded by an Individual for the Purpose of Research and Private Study Only

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. HE IPU WHAKAIRO – INSCRIBING PEACE, KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING: New/beginning social science teachers’ delivery of Treaty of Waitangi and citizenship education in New Zealand Secondary Schools. A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Māori Studies At Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand. Hona Lambert Black 2013 Abstract This thesis examines new/beginning social science teachers’ delivery of Treaty of Waitangi and citizenship education in New Zealand secondary schools. A lack of education about the Treaty and New Zealand citizenship has seen poor understanding amongst our citizenry about the Treaty, race and ethnicity in Aotearoa New Zealand. Research conducted with six new/beginning Māori and non-Māori social science teachers explored, from their perspective, their ability to deliver Treaty and citizenship education based on their teacher training, the New Zealand Curriculum, teaching resources, and their professional development. Mōteatea and whakatauāki, critical consciousness and critical education formed a theoretical base for this work. Individual semi-structured in-depth interviews and thematic analysis were utilized to collect and analyse data, observing Durie’s (1998) ethical framework on ‘mana’. Research findings revealed that Treaty education receives little attention in schools, and teachers, little support to deliver it. For example, although specified within the Curriculum as a learning subject as well as a principle for schools, teachers reported they received no guidance on how to deliver education on the Treaty and were unable to identify how it translated into classroom or school-wide practices. -

Native Decolonization in the Pacific Rim: from the Northwest to New Zealand

NATIVE DECOLONIZATION IN THE PACIFIC RIM: FROM THE NORTHWEST TO NEW ZEALAND KRISTINA ACKLEY AND ZOLTÁN GROSSMAN, FACULTY CLASS TRIP AND STUDENT PROJECTS, THE EVERGREEN STATE COLLEGE, OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON, USA, FEBRUARY-APRIL 2015 KAUPAPA MAORI PRACTICES 1. Aroha ki tangata (a respect for people). 2. Kanohi kitea (the seen face). 3. Titiro, whakarongo…korero (look, listen…speak). 4. Manaaki ki te tangata (share, host people, be generous). 5. Kia tupato (be cautious). 6. Kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata (do not trample over the mana of people). 7. Kaua e mahaki (don’t flaunt your knowledge). Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies (p. 120) Booklet available as a PDF color file: http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/NZ 2015.pdf CONTENTS 3. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION MAPS: 4. New Zealand 5. Maori population and Orakei Maori iwi (tribes) Marae (Maori 2015 STUDY TOUR: 6. Itinerary & Faculty community) 7. Auckland Museums, Feb. 17-18 in Auckland 8. Indigenous Resilience in Auckland, Feb. 16, 19-20 9. Rotorua, Feb. 21-22 10. Whakatane, Feb. 23-24 11. Waipoua Forest, Feb. 25-27 12. Waitangi / Bay of Islands, Feb. 28-Mar. 1 Photos of Study Tour by Zoltán Grossman More photos available at http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/NZ2015.html STUDENT PROJECTS 14. Sarah Bond-Yancey, “The Patterns that Survive: How Indigenous Spatial Resilience Can Inform Inclusive Planning Practices to Guide Our Future” 15. Annie Bouffiou, “Hearing People in a Hard of Hearing Place: If I Did To You What You Do To Me… “ 16. Jessica Cook, “The Indian Child Welfare Act and the Struggles it Faces” 17. -

Annual Report 2014 Victoria University of Wellington Foundation Table of Contents

Annual Report 2014 Victoria University of Wellington Foundation Table of contents Message from the chair ................................2 Universities are unique in providing The trustees ...........................................4 UK and US Friends .....................................5 knowledge and leadership, critical comment S.T. Lee Reading Room .................................6 Pat Walsh Scholarship for second-year students .........8 and a conscience for society. Erika Kremic 1925–2013 ................................9 John David North 1941–2013 ...........................10 In a world where sufficient government Donations received ...................................12 Victoria Benefactors Circle ............................16 funding for universities is no longer assured, Members of the Victoria Benefactors Circle .............18 Victoria Legacy Club ................................. 20 the Victoria University of Wellington Supporting cancer research at Victoria .................22 Foundation exists to raise money for priority Supporting conservation research at Victoria .............24 Disbursements .......................................26 projects at Victoria University that would Reserve Bank Fellows .................................28 Lord King of Lothbury ...............................28 not otherwise be funded. Professor Ross Levine .............................. 29 Financial statements ................................. 30 Victoria University of Wellington Foundation Phone +64-4-463 5991 Email [email protected] -

Articulating a Māori Design Language

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Articulating a Māori Design Language Te Hononga Toi Māori Part 3 A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts at Massey University, Palmerston North. Aotearoa New Zealand Johnson Gordon Paul Witehira Ngāti Hinekura, Tamahaki, Ngāti Hauā, Ngai Tūteauru, Ngā Puhi 2013 Te Hononga Toi Māori (Part 3) was developed by the author as a reference for Māori terms, the Māori design elements and principles, and customary Māori surface pattern. When used in tandem with Toi Runga (Part 1) and Toi Raro (Part 2), Te Hononga Toi Māori (Part 3) acts as quick reference to understanding Māori terms and relevant design terminology. Māori terms are introduced using a convention of Māori term followed by the English translation in brackets and thereafter only the Māori term is used. The Elements and Principles of Māori design In the previous chapters this research sought to explicate the visual language of Māori design through an examination of eighteenth and nineteenth century Māori carved pare (door lintels). Articulating this Māori design language was critical to answering the research question; how can the visual language and tikanga of customary Māori carving be used to inform contemporary Māori design practice? The aim of this thesis is to develop tikanga, or practicing guidelines for contemporary Māori designers.