Picasso by Stein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If I Told Him Stein + Picasso

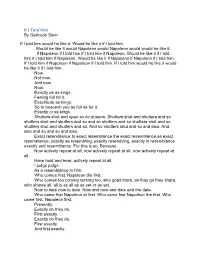

If I Told Him By Gertrude Stein If I told him would he like it. Would he like it if I told him. Would he like it would Napoleon would Napoleon would would he like it. If Napoleon if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him would he like it would he like it if I told him. Now. Not now. And now. Now. Exactly as as kings. Feeling full for it. Exactitude as kings. So to beseech you as full as for it. Exactly or as kings. Shutters shut and open so do queens. Shutters shut and shutters and so shutters shut and shutters and so and so shutters and so shutters shut and so shutters shut and shutters and so. And so shutters shut and so and also. And also and so and so and also. Exact resemblance to exact resemblance the exact resemblance as exact resemblance, exactly as resembling, exactly resembling, exactly in resemblance exactly and resemblance. For this is so. Because. Now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all. Have hold and hear, actively repeat at all. I judge judge. As a resemblance to him. Who comes first. Napoleon the first. Who comes too coming coming too, who goes there, as they go they share, who shares all, all is as all as as yet or as yet. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto Issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perl

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perloff Almost a century has passed since the publication, in the Paris Figaro on 20 February 1909, of a front-page article by F. T. Marinetti called “Le Futurisme” which came to be known as the First Futurist Manifesto [Figure 1]. Famous though this manifesto quickly became, it was just as quickly reviled as a document that endorsed violence, unbridled technology, and war itself as the “hygiene of the people.” Nevertheless, the 1909 manifesto remains the touchstone of what its author called l’arte di far manifesti (“the art of making manifestos”), an art whose recipe—“violence and precision,” “the precise accusation and the well-defined insult”—became the impetus for all later manifesto-art.1 The publication of Günter Berghaus’s comprehensive new edition of Marinetti’s Critical Writings2 affords an excellent opportunity to reconsider the context as well as the rhetoric of Marinetti’s astonishing document. Consider, for starters, that the appearance of the manifesto, originally called Elettricismo or Dinamismo—Marinetti evidently hit on the more general title Futurismo while making revisions in December 2008-- was delayed by an unforeseen event that took place at the turn of 1909. On January 2, 200,000 people were killed in an earthquake in Sicily. As Berghaus tells us, Marinetti realized that this was hardly an opportune moment for startling the world with a literary manifesto, so he delayed publication until he could be sure he would get front-page coverage for his incendiary appeal to lay waste to cultural traditions and institutions. -

The Internet As Playground and Factory November 12–14, 2009 at the New School, New York City

FIRST IN A SERIES OF BIENNIAL CONFERENCES ABOUT THE POLITICS OF DIGITAL MEDIA THE INTERNET AS PLAYGROUND AND FACTORY NOVEMBER 12–14, 2009 AT THE NEW SCHOOL, NEW YORK CITY www.digitallabor.org The conference is sponsored by Eugene Lang College The New School for Liberal Arts and presented in cooperation with the Center for Transformative Media at Parsons The New School for Design, Yale Information Society Project, 16 Beaver Group, The New School for Social Research, The Change You Want To See, The Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New York University’s Council for Media and Culture, and n+1 Magazine. Acknowledgements General Event Support Lula Brown, Alison Campbell, Alex Cline, Conference Director Patrick Fannon, Keith Higgons, Geoff Trebor Scholz Kim, Ellen-Maria Leijonhufvud, Stephanie Lotshaw, Brie Manakul, Lindsey Medeiros, Executive Conference Production Farah Momin, Heather Potts, Katharine Trebor Scholz, Larry Jackson Relth, Jesse Ricke, Joumana Seikaly, Ndelea Simama, Andre Singleton, Lisa Conference Production Taber, Yamberlie Tavarez, Brandon Tonner- Deepthie Welaratna, Farah Momin, Connolly, Jolita Valakaite, Cynthia Wang, Julia P. Carrillo Deepthi Welaratna, Tatiana Zwerling Production of Video Series Voices from Registration Staff The Internet as Playground and Factory Alison Campbell, Alex Cline, Keith Higgons, Assal Ghawami Geoff Kim, Stephanie Lotshaw, Brie Manakul, Overture Video Lindsey Medeiros, Heather Potts, Jesse Assal Ghawami Ricke, Joumana Seikaly, Andre Singleton, Deepthi Welaratna, Tatiana Zwerling Video -

Defamiliarization: Flarf, Conceptual Writing, and Using Flawed Software Tools As Creative Partners Richard P. Gabriel*

Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, Vol.4, No.2. 134 Defamiliarization: Flarf, conceptual writing, and using flawed software tools as creative partners Richard P. Gabriel* IBM Research 3636 Altamont Way, Redwood City CA 94062, USA E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract: One form of creativity uses defamiliarization, a mechanism that frees the brain from its rational shackles and permits the abducing brain to run free. Mistakes and flaws in several software tools are shown to be the starting points for increased creativity and better art, and a theory explaining the phenomenon is proposed. Keywords: Writing; Poetry; Creativity; Flarf Biographical notes: Richard P. Gabriel received a PhD in Computer Science from Stanford University in 1981, and an MFA in Poetry from Warren Wilson College in 1998. He has been a researcher at Stanford University, company president and Chief Technical Officer at Lucid, Inc., vice president of Development at ParcPlace-Digitalk, a management consultant for several startups, a Distinguished Engineer at Sun Microsystems, and Consulting Professor of Computer Science at Stanford University. He is an ACM Fellow. He is a researcher at IBM Research, looking into the architecture, design, and implementation of extraordinarily large, self-sustaining systems as well as development techniques for building them. Until recently he was President of the Hillside Group, a nonprofit that nurtures the software patterns community by holding conferences, publishing books, -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Montmartre the Tour: La Place Des Abbesses (The Abbesses Square), the Small Streets, La Place Du Tertre (The Tertre Square), Le Sacré-Coeur (The Sacred Heart)

MONTMARTRE THE TOUR: LA PLACE DES ABBESSES (THE ABBESSES SQUARE), THE SMALL STREETS, LA PLACE DU TERTRE (THE TERTRE SQUARE), LE SACRÉ-COEUR (THE SACRED HEART) LE SACRÉ-COEUR THE SMALL STREETS LA PLACE DU TERTRE LES ABBESSES Lenght: Means of locomotion: on foot - 3H00 walking, Access for persons with reduced - half a day: walking + visit of the mobility : no Sacré-Coeur, Total distance: 4km - the entire day: walking + visit of Starting point: Place des Abbesses the Sacré-Coeur, the Montmartre (metro line 12, Abbesses station, museum and the Dali area. or the Montmartrobus Abbesses station) Public: All restaurant, « Le Relais de la Butte » (The Mound Inn), once called « Chez Azon » (At Azon’s). At the beginning of the 20th century, Father Azon gladly welcomed and fed all the penniless artists from the bateau- lavoir who paid him with works of art... which did not prevent him from Take rue des Abbesses going bankrupt ! (Abbesses Street) on your right and keep going forward for about 50 Climb the steps of this Emile metres. Goudeau small square (ex Ravignan Square). It is the same quietness At the Abbesses passage entrance, impression that we found in the on your right, graffities, drawings, Place des Abbesses, with benches, stencils and other inlays are trees, the big Wallace fountain, and animating the walls. some funny graffities. Pay close attention, you will have the opportunity to see many others On your left, with your back turned throughout the walk. to the steps, stands a recently cleaned building with white blinds Carry on and take rue Ravignan and green doors is the famous (Ravignan Street) on your right. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Conceptualisms, Old and New Marjorie Perloff Before Conceptual Art Became Prominent in the Late 1960S, There Was Already, So

Conceptualisms, Old and New Marjorie Perloff Before conceptual art became prominent in the late 1960s, there was already, so Craig Dworkin has suggested in his “Anthology of Conceptual Writing” for Ubu Web (http://www.ubu.com/), a form of writing identifiable as conceptual poetry, although that term was not normally used to discuss the chance-generated texts of John Cage and Jackson Mac Low or the “word events” of George Brecht and La Monte Young. In his Introduction to the Ubu Web anthology, Dworkin makes an interesting case for a “non- expressive poetry,” “a poetry of intellect rather than emotion,” in which “the substitutions at the heart of metaphor and image were replaced by the direct presentation of language itself, with [Wordsworth’s] ‘spontaneous overflow [ of powerful feelings]’ supplanted by meticulous procedure and exhaustively logical process.” The first poet in Dworkin’s alphabetically arranged anthology of conceptual writing is Vito Acconci, whose early “poetry,” most of it previously unpublished, has now been edited and assembled, again by Dworkin for a hefty (411-page) volume called Language to Cover a Page, published in MIT Press’s Writing Art Series (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006). I place poetry in quotes here because, strictly speaking, Acconci’s word texts —constraint-based lists, dictionary games, performance scores, or parodic translations-- are not so much poems as they are, in the Wittgensteinian sense, complex language games, in which the page has not yet been replaced by the video screen, the tape length, or the gallery space. Indeed, as Dworkin argues in an earlier piece on Acconci for October (95 [Winter 2001], pp. -

The Radical Ekphrasis of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2018 The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Googer, Georgia, "The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons" (2018). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 889. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/889 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RADICAL EKPHRASIS OF GERTRUDE STEIN’S TENDER BUTTONS A Thesis Presented by Georgia Googer to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2018 Defense Date: March 21, 2018 Thesis Examination Committee: Mary Louise Kete, Ph.D., Advisor Melanie S. Gustafson, Ph.D., Chairperson Eric R. Lindstrom, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT This thesis offers a reading of Gertrude Stein’s 1914 prose poetry collection, Tender Buttons, as a radical experiment in ekphrasis. A project that began with an examination of the avant-garde imagism movement in the early twentieth century, this thesis notes how Stein’s work differs from her Imagist contemporaries through an exploration of material spaces and objects as immersive sensory experiences. This thesis draws on late twentieth century attempts to understand and define ekphrastic poetry before turning to Tender Buttons. -

![Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/ida-a-performative-novel-and-the-construction-of-id-entity-1024638.webp)

Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity

Wesleyan University The Honors College Ida, A [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity by Katherine Malczewski Class of 2015 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Theater Middletown, Connecticut April, 2015 Malczewski 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………3 Stein’s Theoretical Framework………………………………………………………..4 Stein’s Writing Process and Techniques……………………………………………..12 Ida, A Novel: Context and Textual Analysis………………………………...……….17 Stein’s Theater, the Aesthetics of the Performative, and the Actor’s Work in Ida…………………………………………………25 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………...40 Notes…………………………………………………………………………………41 Appendix: Adaptation of Ida, A Novel……………………………....………………44 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….56 Malczewski 2 Acknowledgments Many thanks to all the people who have supported me throughout this process: To my director, advisor, and mentor, Cláudia Tatinge Nascimento. You ignited my passion for both the works of Gertrude Stein and “weird” theater during my freshman year by casting me in Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights. Since then, you have offered me with invaluable guidance and insight, teaching me that the process is just as important as the performance. I am eternally grateful for all the time and energy you have dedicated to this project. To the Wesleyan Theater Department, for guiding me throughout my four years at Wesleyan, encouraging me to embrace collaboration, and making the performance of Ida, A Novel possible. Special thanks to Marcela Oteíza and Leslie Weinberg, for your help and advice during the process of Ida. To my English advisors, Courtney Weiss Smith and Rachel Ellis Neyra, for challenging me to think critically and making me a better writer in the process. -

Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287

Picasso and Braque A SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZED BY William Rubin \ MODERATED BY Kirk Varnedoe PROCEEDINGS EDITED BY Lynn Zelevansky THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK Contents Richard E. Oldenburg Foreword 7 William Rubin and Preface and Acknowledgments 9 Lynn Zelevansky Theodore Reff The Reaction Against Fauvism: The Case of Braque 17 Discussion 44 David Cottington Cubism, Aestheticism, Modernism 58 Discussion 73 Edward F. Fry Convergence of Traditions: The Cubism of Picasso and Braque 92 Discussion i07 Christine Poggi Braque’s Early Papiers Colles: The Certainties o/Faux Bois 129 Discussion 150 Yve-Alain Bois The Semiology of Cubism 169 Discussion 209 Mark Roskill Braque’s Papiers Colles and the Feminine Side to Cubism 222 Discussion 240 Rosalind Krauss The Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287 Pierre Daix Appe ndix 1 306 The Chronology of Proto-Cubism: New Data on the Opening of the Picasso/Braque Dialogue Pepe Karmel Appe ndix 2 322 Notes on the Dating of Works Participants in the Symposium 351 The Motivation of the Sign ROSALIND RRAUSS Perhaps we should start at the center of the argument, with a reading of a papier colle by Picasso. This object, from the group dated late November-December 1912, comes from that phase of Picasso’s exploration in which the collage vocabulary has been reduced to a minimalist austerity. For in this run Picasso restricts his palette of pasted mate rial almost exclusively to newsprint. Indeed, in the papier colle in question, Violin (fig. 1), two newsprint fragments, one of them bearing h dispatch from the Balkans datelined TCHATALDJA, are imported into the graphic atmosphere of charcoal and drawing paper as the sole elements added to its surface.