Summit Tool Box Turning Community Interest Into Environmental Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation Framework and Its Testing in the South Georgian Bay Region SUMMARY

Premier Ranked Tourist Destinations: An Evaluation Framework and Its Testing in the South Georgian Bay Region SUMMARY PREMIER RANKED TOURIST DESTINATION PRODUCT PERFORMANCE FUTURITY A. Distinctive Core Attractions F. Visitation I. DestiInation Marketing AI A2 F1 F2 F3 I1 I2 I3 A1.i A1.v A2.i F1.i F2.i F3.i I1.i I2.i I3.i A1.ii A1.vii A2.ii F1.ii I1.ii I2.ii A1.iii A1.viii A2.iii F1.iii I2.iii A1.iv A1.ix F1.iv A1.v A1.x F1.v I4 F1.vi I4.i B. Quality and Critical Mass F1.vii J. Product Renewal B1 B2 B3 G. Occupancy and Yield B1.i B2.i B3.i J1 B1.ii B2.ii B3.ii G1 G2 J1.i B1.iii G1.i G2.i J1.ii B1.iv G1.ii G2.ii J1.iii G2.iii B4 B5 B6 G2.iv K. Managing w‘in Carryiing Capacities B4.i B5.i B6.i B4.ii B5.ii B6.ii H. Critical Acclaim K1 K2 K3 B4.iii B6.iii K1.i K2.i K3.i B4.iv B6.iv H1 H2 H3 K1.ii K2.ii K3.ii H1.i H2.i H3.i K2.iii K3.iii B7 H1.ii B7.i K4 K5 K6 B7.ii K4.i K5.i K6.i K4.ii K5.ii K6.ii C. Satisfaction and Value K4.iii K5.iii K6.iii K4.iv K6.iv C1 C2 C3 C1.i C2.i C3.i K7 C1.ii C2.ii C3.ii K7.i C3.iii K7.ii K7.iii D. -

Town of Collingwood Community Profile

2015 Community Profile 2013 V 1.3 May 2015 © 2015 Town of Collingwood Information in this document is subject to change without notice. Although all data is believed to be the most accurate and up-to-date, the reader is advised to verify all data before making any decisions based upon the information contained in this document. For further information, please contact: Martin Rydlo Director, Marketing and Business Development Town of Collingwood 105 Hurontario Street PO Box 157, Collingwood, ON L9Y 3Z5 Phone: 705-445-8441 x7421 Email: [email protected] Web: www.collingwood.ca Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Location ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Climate .............................................................................................................................. 4 2 DEMOGRAPHICS ........................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Population Size and Growth ................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Age Profile ......................................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Language Characteristics .................................................................................................... -

Georgian Triangle Literacy Service Plan

2011-2012 Georgian Triangle Literacy Service Plan 1 Acknowledgements Many thanks are extended to the Georgian Triangle Literacy Service Planning Committee for their dedication and assistance in preparing this report. Appreciation is expressed to the Board of Directors and staff of QUILL (Quality in Lifelong) Learning Network for their assistance and commitment to literacy planning. Debera Flynn, Executive Director The Georgian Triangle Literacy Service Planning Committee Lynn Hynd, Georgian College Lisa Wiley, Georgian College Roger Hannon, Georgian Learning Charlotte Parliament, Simcoe County District School Board Debera Flynn, QUILL Learning Network QUILL Learning Network 104 Catherine Street Box 1148 Walkerton, ON N0G 2VO Telephone: 519-881-4655 Toll free: 800-530-6852 Fax: 519-881-4638 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.quillnetwork.ca The QUILL Learning Network is funded by the Government of Ontario. The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Ontario. 2 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 2 Literacy and Basic Skills in the Georgian Triangle ........................................................ 5 Snapshot of activity in the Georgian Triangle ............................................................... 5 Highlights of Delivery in the QUILL Region ................................................................ 6 Environmental Scan ......................................................................................................... -

Navigation Canals

Rideau Indian and Affaires indiennes Navigation Northern Affairs et du Nord Trent Parks Canada Parcs Canada Canals Québec Cover: Between locks 22 and 23 St. Peters in the second basin at Merrickville on the Rideau Canal. Navigation Canals Rideau Trent Québec St. Peters Published by Parks Canada under authority of the Hon. Warren Allmand, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, Ottawa, 1977 QS-1194-000-BB-A5 ©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1977 Catalogue No. R58-2/1977 ISBN 0-662-00816-2 3 CONTENTS SECTION SUB-SECTION DESCRIPTION PAGE Inside front cover Location of Navigation Canals 1 GENERAL INFORMATION 4 1—1 Introduction 4 1—2 Location 4 1—3 Navigation Charts 4 1—4 Canal Vessel Permits and Tolls 4 2 CRUISING INFORMATION APPLICABLE TO ALL THE CANAL SYSTEMS 5 2—1 Canal Regulations 5 2—2 Licensing of Vessels 5 2—3 Speed Limits 5 2—4 Limiting Dimensions 5 2—5 Vessel Clearances 5 2—6 Comments 5 2—7 Clearance Papers 5 2—8 Approach Wharves 5 2—9 Aids to Navigation 6 2—10 Signals for Locks and Bridges 6 2-11 Power Outlets 6 2-12 Ships' Reports 6 2-13 Pollution 6 2—14 Boat Campers 6 2-15 Weed Obstructions 6 2—16 Literature Published by the Provincial Governments 6 2—17 Fire Prevention 6 3 TRENT CANAL SYSTEM 7 3-1 Charts 7 3-2 Storms and Squalls —Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching 7 3-3 Big Chute Marine Railway 7 3-4 Channel below Big Chute, Mile 232.5 7 3-5 Traffic Lights 7 3-6 Radio Stations 7 3-7 Canal Lake and Mitchell Lake 7 3-8 Mileage and General Data 8-13 4 RIDEAU CANAL SYSTEM 15 4-1 Charts 15 4-2 Traffic Lights 15 4-3 Radio Stations 15 4-4 Mileage and General Data 16-19 5 QUEBEC CANALS 21 5-1 Charts 21 5-2 Radio Stations 21 5-3 Richelieu River Route 21 5-4 Montréal-Ottawa Route 21 5-5 Mileage and General Data 24 6 ATLANTIC OCEAN TO BRAS D'OR LAKES ROUTE 27 6-1 St. -

Blue Mountains – Collingwood - Wasaga Beach – Clearview Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan 1 July 2010

Blue Mountains – Collingwood - Wasaga Beach – Clearview Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan 1 July 2010 December 24, 2010 South Georgian Bay Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan Support for this Study Provided by the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Trade South Georgian Bay Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan The Blue Mountains - Clearview - Collingwood - Wasaga Beach Entrepreneur Targets ............................................................... 67 Education ........................................................................................ 70 Table of Contents Economic Impact of Post-Secondary Education ................... 73 Workforce Development ................................................................ 76 South Georgian Bay Regional Economic Development A Creative Community .................................................................... 77 Strategic Plan .............................................................................. 1 SWOT Analysis ................................................................................ 79 The Blue Mountains - Clearview - Collingwood - Wasaga Strengths ................................................................................... 79 Beach ........................................................................................... 1 Weaknesses............................................................................... 79 Opportunities............................................................................ 80 Introduction -

View TOP Report

TRENDS OPPORTUNITIES PRIORITIES TOP REPORT January 2008 a member of Champions of Ontario’s Local Labour Market Solutions ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks are extended to Todd Gordon for his assistance with research. Appreciation is expressed to Eileen Comars, Consultations Facilitator; the Bruce Grey Huron Perth Georgian Triangle Training Board Staff and its Directors for their assistance and dedication to community planning. Gemma Mendez-Smith, Executive Director BRUCE GREY HURON PERTH GEORGIAN TRIANGLE TRAINING BOARD DIRECTORS Business: Catherine Durrant, Cavell Fraser, David Hemingway, Jayne Parker, Rosemary Rognvaldson (Co-Chair) Labour: Dave Jasper, Jill McIllwraith, Al Mossman, Charlie Nixon (Co-Chair) Aboriginal: Pamela Keeshig Equity: Dwayne Long Educator/Trainer: Jo-Anne Cameron, Jay Notay Youth: Megan Braithwaite MTCU Advisor: Lauri Cunningham Bruce Grey Huron Perth Georgian Triangle Training Board 111 Jackson Street, Suite 1, Box 1078 Walkerton, Ontario, N0G 2V0 Toll-free: 1-888-774-1468 T (519) 881-2725 F (519) 881-3661 [email protected] www.trainingboard.ca The Bruce Grey Huron Perth Georgian Triangle Training Board is funded by the Government of Ontario. The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Ontario TRENDS OPPORTUNITIES Contents PRIORITIES TOP REPORT Executive Summary ...........................................................................................................2 Introduction .....................................................................................................................2 -

Simcoe County Community Directory.Pdf

Community Directory SIMCOE COUNTY Community Directory Simcoe Muskoka Workforce Development Board www.smwdb.com SIMCOE COUNTY Simcoe Muskoka Workforce Development Board www.smwdb.com Table of Contents 3 Emergency Information 8 211 Information 10 Health & Health Services 23 Food Banks & Non-emergency Housing 27 Education 32 Employment 36 Children, Youth & Families 44 Seniors 47 Recreation 50 Transportation 53 Financial Support & Services 55 Legal Information & Support 59 General Information 2 Community Directory Simcoe County Emergency Information POLICE/FIRE/AMBULANCE 9-1-1 O.P.P. (Ontario Provincial Police) 1-888-310-1122 Mental Health Crisis Numbers Mental Health Crisis Line 1-888-893-8333 - Crisis Line Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) 705-728-5044 Simcoe County Branch, 15 & 21 Bradford Street, Barrie Ontario Mental Health Helpline - Connex 1-866-531-2600 Available in 170 languages Mental Health Crisis Line www.connexontario.ca Suicide Hotline 1-888-893-8333 Telecare Distress Line of Greater Simcoe 705-327-2383 Available 24/7 705-325-9534 705-726-7922 - Crisis Line Youth Mobile Crisis Response Simcoe County 1-888-893-8333 - Crisis Line Kinark Child & Family Services 705-728-5044 34 Simcoe Street, Unit 301, Barrie That all local hospitals help people who are having a serious mental health crisis. See page10 for a listing of local hospitals. Emergency Information Please see our most current version online at: www.smwdb.com 3 Sexual Assault Help Lines Assaulted Women’s 24 Hour Helpline 1-866-863-0511 www.awhl.org French 1-877-336-2433 -

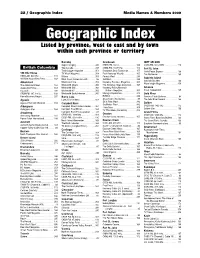

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Blue Mountains – Collingwood - Wasaga Beach – Clearview Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan 1 July 2010

Blue Mountains – Collingwood - Wasaga Beach – Clearview Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan 1 July 2010 June 2011 South Georgian Bay Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan Support for this Study Provided by the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Trade South Georgian Bay Regional Economic Development Strategic Plan The Blue Mountains - Clearview - Collingwood - Wasaga Beach Entrepreneur Targets ............................................................... 67 Education ........................................................................................ 70 Table of Contents Economic Impact of Post-Secondary Education ................... 73 Workforce Development ................................................................ 76 South Georgian Bay Regional Economic Development A Creative Community .................................................................... 77 Strategic Plan .............................................................................. 1 SWOT Analysis ................................................................................ 79 The Blue Mountains - Clearview - Collingwood - Wasaga Strengths ................................................................................... 79 Beach ........................................................................................... 1 Weaknesses............................................................................... 79 Opportunities............................................................................ 80 Introduction ............................................................................... -

Visit South Georgian Bay Clearview Collingwood Meaford the Blue Mountains Wasaga Beach

VISITSOUTHGEORGIANBAY.CA VISIT SOUTH GEORGIAN BAY CLEARVIEW COLLINGWOOD MEAFORD THE BLUE MOUNTAINS WASAGA BEACH GuideSee&Do What’s UltimatePLAYGROUND Winter your Adventure? South Georgian Bay is packed full of things to do in winter. When there’s snow on the ground, you can snowshoe almost anywhere where you’d normally hike. Our resorts and inns provide convenient access to the best winter outdoor activities plus hearty meals and warm après-ski hospitality. The Niagara Escarpment through varied terrain. Riders control their own speeds—up to 42 km/h (26 Re-connect with nature in ancient forests along the mph). bluemountain.ca Niagara Escarpment, a UNESCO world biosphere reserve. The Bruce Trail is Canada’s oldest marked footpath and crosses Ontario from Niagara Falls through to Tobermory along the Niagara Escarpment. Exercise caution in winter, follow recommended trail usage. Scandinave Spa Blue Mountain The award-winning Scandinave Spa Blue Mountain offers the unique Scandinavian Baths experience. Situated in a natural forest, minutes from downtown Collingwood & Blue Mountain Resort, guests are encouraged to enjoy the serenity of the outdoors year-round. The Scandinavian Baths include a new Infra-red Sauna, recently renovated Finnish Sauna, Eucalyptus Steam Room, Thermal & Nordic Waterfalls, Hot Baths, Cold Plunges, fireplaces and expansive indoor and outdoor relaxation areas. Also available are Registered Massage reservations, getaway packages with local accommodators as well as a casual bistro serving healthy local fare. scandinave.com Ridge Runner Mountain Coaster TOWN OF THE BLUE MOUNTAINS Ontario’s first mountain coaster offers an exciting down- Thornbury ● Clarksburg ● Blue Mountain Village hill adventure at Blue Mountain. -

WBVGB 2018 Final Feb 15.Indd

Welcome • Bienvenue WASAGA BEACH THE WORLD’S LONGEST FRESHWATER BEACH MAIN OFFICE BRANCH OFFICE SUMMER BEACH OFFICE 1263 Mosley Street (Riverbend Plaza) 1900 Mosley Street (45th & Mosley) 35 Mosley Street (Near Main St Bridge) 705-429-4500 705-429-5500 705-429-4500 Andrew McKay Michelle Seip Rick Seip Rochelle Reid Ava Alward Wayne Sheilds Jason Ruttan Marilyn Ruttan Sales Representative Broker Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Broker/Owner Broker of Record Mark Ruttan Adriana Ruttan David Scott Nicole Spooner Melissa McGillvray Bruce Johnson Susan Bowins Anna Bond Bobby Novakovic Broker Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Broker Sales Representative Sales Representative Cindy Booth-Ford Debbie Williamson Jeremy Ruttan Jessica Bigalke Ron Puccini Jane Puccini Lotti Matthews Sanjay Kapoor Don Goulding Sales Representative Broker Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative View our NEW LISTINGS each week on Facebook www.facebook.com/RemaxWasagaBeach Check out our Instragram for NEWS and UPDATES www.instagram.com/remaxwasagabeach Sandra Boland Dean Raven Scott Bradley Pat Magda Joyce Edwards Gary Storey Great home decor & seasonal decorating ideas Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Sales Representative Broker www.pinterest.com/RemaxWasaga www.WasagaBeachHomes.com Welcome • Bienvenue What's Inside Hello and welcome to Wasaga Beach. 3-4 WELCOME MESSAGES On behalf of council members and our local community, I want to 6 IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS thank you for choosing to spend time in our town. Whether your 7 WHEELCHAIR ACCESSIBILITY visit is business or pleasure, we are grateful you made our community 8 MAIN STREET MARKET your destination. -

Town of Collingwood Economic Development Action Plan Final Report

Town of Collingwood Economic Development Action Plan Final Report Prepared by: May 2015 Town of Collingwood Economic Development Action Plan Final Report Prepared by: McSweeney & Associates McSweeney & Associates 201 - 900 Greenbank Road Ottawa, Ontario CANADA K2J 1S8 Phone: 1-855-300-8548 Fax: 1-866-299-4313 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mcsweeney.ca Collingwood Economic Development Action Plan Final Report Table of Contents 1 Economic Development Action Plan Overview ............................................. 1 2 Collingwood’s Economic Development Action Plan ...................................... 1 2.1 Business Service Priority ...................................................................................... 2 2.2 Existing Business Support .................................................................................... 3 2.3 Small Business Growth ........................................................................................ 4 2.4 Business and Tourism Promotion .......................................................................... 5 2.5 Great Place for Business ...................................................................................... 6 2.6 Workforce at Work .............................................................................................. 7 3 Process Followed .......................................................................................... 8 4 Snapshot of Collingwood by the Numbers .................................................... 9 4.1 Demographics ...................................................................................................