Case Studies of Large Outdoor Fires Involving Evacuations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TESTIMONY of RANDY MOORE, REGIONAL FORESTER PACIFIC SOUTHWEST REGION UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of AGRICULTURE—FOREST SERVICE BE

TESTIMONY of RANDY MOORE, REGIONAL FORESTER PACIFIC SOUTHWEST REGION UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE—FOREST SERVICE BEFORE THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM—SUBCOMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENT August 20, 2019 Concerning WILDFIRE RESPONSE AND RECOVERY EFFORTS IN CALIFORNIA Chairman Rouda, Ranking Member and Members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss wildfire response and recovery efforts in California. My testimony today will focus on the 2017-2018 fire seasons, as well as the forecasted 2019 wildfire activity this summer and fall. I will also provide an overview of the Forest Service’s wildfire mitigation strategies, including ways the Forest Service is working with its many partners to improve forest conditions and help communities prepare for wildfire. 2017 AND 2018 WILDIRES AND RELATED RECOVERY EFFORTS In the past two years, California has experienced the deadliest and most destructive wildfires in its recorded history. More than 17,000 wildfires burned over three million acres across all land ownerships, which is almost three percent of California’s land mass. These fires tragically killed 146 people, burned down tens of thousands of homes and businesses and destroyed billions of dollars of property and infrastructure. In California alone, the Forest Service spent $860 million on fire suppression in 2017 and 2018. In 2017, wind-driven fires in Napa and neighboring counties in Northern California tragically claimed more than 40 lives, burned over 245,000 acres, destroyed approximately 8,900 structures and had over 11,000 firefighters assigned. In Southern California, the Thomas Fire burned over 280,000 acres, destroying over 1,000 structures and forced approximately 100,000 people to evacuate. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Understanding Wildland Fire and Preparedness in San Diego County Working with North County Fire Protection District

Understanding Wildland Fire and Preparedness in San Diego County Working with North County Fire Protection District Understanding the Threat of Wildland Fire The Threat of Wildland Fire in Our Area? – Gavilan Fire (February 10, 2002) – Cedar Fire (October, 2003) – Paradise Fire (October, 2003) – Rice Fire (October 22, 2007) – Cocos, Highway Fire (May 2014) Understanding the Threat of Wildland Fire • What Drives Wildland Fires in Your Area? – California’s Native Plants are among the most Flammable in the World – Topography – Hot, dry Santa Anna Winds – Year-round Fire Season 2012 Wildland Fire Frequency Mapping The Ready, Set, Go! Program (RSG) • RSG Personal Wildland Fire Action Plan – Family and Property Preparation The Goal is to learn how to improve your homes resistance to wildfires and prepare your family to leave EARLY in a safe manner. National Level Response • Creating Communities Adapted to the Fire Threat - Collaborative efforts at the community level - RSG and is a national tool for this effort - Learn more at www.iafc.org/FAC and www.FireAdapted.org Ready : Prepare your home and family • Home: Creating Defensible Space and Hardening the structure • Family: Create a Family Disaster Plan ReadySandiego.org Alert San Diego Wildland Fire Environment SD Counties Damage assessment team 2007 Rice Fire in Fallbrook: The two main reasons homes were lost: 1. Lack of Defensible Space (Homes overgrown with flammable vegetation) 2. Lack of Ignition Resistant Construction (Homes built to burn) Create Defensible Space Protecting your home from wildfire damage requires limiting the amount of fuel that could bring flames and embers dangerously close to your property. -

Spatiotemporal Patterns of Population Mobility and Its Determinants in Chinese Cities Based on Travel Big Data

sustainability Article Spatiotemporal Patterns of Population Mobility and Its Determinants in Chinese Cities Based on Travel Big Data Zhen Yang 1,2 , Weijun Gao 1,2,* , Xueyuan Zhao 1,2, Chibiao Hao 3 and Xudong Xie 3 1 Innovation Institute for Sustainable Maritime Architecture Research and Technology, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao 266033, China; [email protected] (Z.Y.); [email protected] (X.Z.) 2 Faculty of Environmental Engineering, The University of Kitakyushu, Kitakyushu 808-0135, Japan 3 College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao 266033, China; [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (X.X.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-93-695-3234 Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 13 May 2020; Published: 14 May 2020 Abstract: Large-scale population mobility has an important impact on the spatial layout of China’s urban systems. Compared with traditional census data, mobile-phone-based travel big data can describe the mobility patterns of a population in a timely, dynamic, complete, and accurate manner. With the travel big dataset supported by Tencent’s location big data, combined with social network analysis (SNA) and a semiparametric geographically weighted regression (SGWR) model, this paper first analyzed the spatiotemporal patterns and characteristics of mobile-data-based population mobility (MBPM), and then revealed the socioeconomic factors related to population mobility during the Spring Festival of 2019, which is the most important festival in China, equivalent to Thanksgiving Day in United States. During this period, the volume of population mobility exceeded 200 million, which became the largest time node of short-term population mobility in the world. -

Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019

REVIEW OF CALIFORNIA WILDFIRE EVACUATIONS FROM 2017 TO 2019 STEPHEN WONG, JACQUELYN BROADER, AND SUSAN SHAHEEN, PH.D. MARCH 2020 DOI: 10.7922/G2WW7FVK DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R Wong, Broader, Shaheen 2 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2019-19-b N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019 March 2020 6. Performing Organization Code ITS-Berkeley 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report Stephen D. Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3638-3651), No. Jacquelyn C. Broader (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3269-955X), N/A Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3350-856X) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, Berkeley N/A 109 McLaughlin Hall, MC1720 11. Contract or Grant No. Berkeley, CA 94720-1720 UC-ITS-2019-19 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period The University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Covered www.ucits.org Final Report 14. Sponsoring Agency Code UC ITS 15. Supplementary Notes DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R 16. Abstract Between 2017 and 2019, California experienced a series of devastating wildfires that together led over one million people to be ordered to evacuate. Due to the speed of many of these wildfires, residents across California found themselves in challenging evacuation situations, often at night and with little time to escape. These evacuations placed considerable stress on public resources and infrastructure for both transportation and sheltering. -

Iacp New Members

44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 200 | Alexandria, VA 22314, USA | 703.836.6767 or 1.800.THEIACP | www.theIACP.org IACP NEW MEMBERS New member applications are published pursuant to the provisions of the IACP Constitution. If any active member in good standing objects to an applicant, written notice of the objection must be submitted to the Executive Director within 60 days of publication. The full membership listing can be found in the online member directory under the Participate tab of the IACP website. Associate members are indicated with an asterisk (*). All other listings are active members. Published July 1, 2021. Australia Australian Capital Territory Canberra *Sanders, Katrina, Chief Medical Officer, Australian Federal Police New South Wales Parramatta Walton, Mark S, Assistant Commissioner, New South Wales Police Force Victoria Melbourne *Harman, Brett, Inspector, Victoria Police Force Canada Alberta Edmonton *Cardinal, Jocelyn, Corporal Peer to Peer Coordinator, Royal Canadian Mounted Police *Formstone, Michelle, IT Manager/Business Technology Transformation, Edmonton Police Service *Hagen, Deanna, Constable, Royal Canadian Mounted Police *Seyler, Clair, Corporate Communications, Edmonton Police Service Lac La Biche *Young, Aaron, Law Enforcement Training Instructor, Lac La Biche Enforcement Services British Columbia Delta *Bentley, Steven, Constable, Delta Police Department Nelson Fisher, Donovan, Chief Constable, Nelson Police Department New Westminster *Wlodyka, Art, Constable, New Westminster Police Department Surrey *Cassidy, -

2019 Wildland Fire Season

Pacific Northwest Fire and Aviation Management 2019 WILDLAND FIRE SEASON A cooperative effort between the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of the Interior 1 The 204 Cow Fire, ignited by lightning in August 2019 on the Malheur National Forest, was managed to reduce fuel build-up and restore forest health in an area dominated by beetle- killed trees that had not seen fire in 30 years. Photo Credit: Michael Haas Cover: The lightning-caused Granite Gulch Fire, which started in July 2019, burned in a remote part of the Eagle Cap Wilderness within the Wallowa- Whitman National Forest and was successfully managed to restore ecosystem resiliency. USFS Photo 2 A Season of Extremes: Opportunities in Oregon and Washington, Challenges in Alaska The 2019 fire season was short and inexpensive compared to past years in Oregon and Washington. Resources were on board and ready for an active fire year. Yet, the level of fire activity and resource commitment remained well below what has been experienced in recent years. Recurrent precipitation kept most of the geographic area at or below average levels of fuels dryness. The fuel moisture retention helped minimize severe wildfire activity and enabled firefighters to quickly contain hundreds of fires during initial attack. In Alaska, the situation was very different. Fire conditions warranted the highest preparedness level for an extended period of time. Resources from Oregon and Washington were sent to assist with a long and challenging season. While Alaska focused on wildfire suppression, Oregon and Washington seized opportunities to promote resilient landscapes through proactive fire management when conditions allowed. -

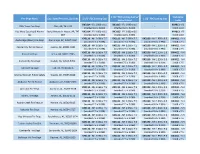

Fire Dept Name City, State/Province, Zip Code 2 1/2" FDC Locking Cap 2

2 1/2" FDC Locking Cap w/ Standpipe Fire Dept Name City, State/Province, Zip Code 2 1/2" FDC Locking Cap 1 1/2" FDC Locking Cap Swivel Guard Locks KX3114 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX3115 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX4013 - FD Olds Town Fire Dept Olds, AB, T4H 1R5 - (marked 8.0 x 3.000) (marked 8.0 x 3.000) 3.000 x 8.0 Key West Security & Alarms Rocky Mountain House, AB, T4T KX3114 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX3115 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX4013 - FD - Inc 1B7 (marked 8.0 x 3.000) (marked 8.0 x 3.000) 3.000 x 8.0 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Anchorage (Muni) Fire Dept Anchorage, AK, 99507-1554 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Capital City Fire & Rescue Juneau, AK, 99801-1845 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Kenai Fire Dept Kenai, AK, 99611-7745 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Kodiak City Fire Dept Kodiak, AK, 99615-6352 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Tok Vol Fire Dept Tok, AK, 99780-0076 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH -

Temporal-Relational Hypergraph Tri-Attention Networks for Stock

JOURNAL OF LATEX CLASS FILES, VOL. 14, NO. 8, AUGUST 2015 1 Temporal-Relational Hypergraph Tri-Attention Networks for Stock Trend Prediction Chaoran Cui, Xiaojie Li, Juan Du, Chunyun Zhang, Xiushan Nie, Meng Wang, and Yilong Yin Abstract—Predicting the future price trends of stocks is a trend prediction, which aims to forecast the future price trends challenging yet intriguing problem given its critical role to help of stocks, has received increasing attention due to its potential investors make profitable decisions. In this paper, we present a in helping investors make profitable decisions. Although the collaborative temporal-relational modeling framework for end- to-end stock trend prediction. The temporal dynamics of stocks famous efficient market hypothesis [1] holds a pessimistic is firstly captured with an attention-based recurrent neural view that the future price of a stock is unpredictable with network. Then, different from existing studies relying on the respect to currently available information, continuous research pairwise correlations between stocks, we argue that stocks are works [2]–[4] on stock trend prediction have achieved impres- naturally connected as a collective group, and introduce the sive success in past decades, and provided strong evidence for hypergraph structures to jointly characterize the stock group- wise relationships of industry-belonging and fund-holding. A the predictability of stock markets. novel hypergraph tri-attention network (HGTAN) is proposed A natural solution to stock trend prediction is to regard it as to augment the hypergraph convolutional networks with a hier- a time series modeling problem, for which the autoregressive archical organization of intra-hyperedge, inter-hyperedge, and model and its variants [5] were initially applied to fit the inter-hypergraph attention modules. -

FEBRUARY 2016 2 BLUE LINE MAGAZINE February, 2016 Volume 28 Number 2

FEBRUARY 2016 2 BLUE LINE MAGAZINE February, 2016 Volume 28 Number 2 Features 6 People Helping People An alternate mental health crisis response model 10 Duties to Fulfill Unique agency keeps Alberta communities resilient 12 Promoting Diversity “Serving with Pride” leads the way for police in Ontario Cover Shot: Alana Holtom 6 14 Doing Everything with Nothing Communities need to understand the cost of modern policing 10 18 Truth, Reconciliation and the RCMP Departments 46 Advertisers Index 20 Deep Blue 44 Dispatches 38 Holding the Line 45 Market Place 44 Showcase 43 Product News 5 Publisher’s Commentary 12 36 Technology Case Law 40 Arrest grounds depend on all circumstances 41 Secondary purpose didn’t taint stop legality BLUE LINE MAGAZINE 3 FEBRUARY 2016 FEBRUARY 2016 4 BLUE LINE MAGAZINE PUBLISHER’S COMMENTARY Blue Line by Morley Lymburner Magazine Inc. PUBLISHER Engaging a Charter Right Morley S. Lymburner – [email protected] ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER The Canadian aversion to arming paral- show a glimmer of understanding the risks. Kathryn Lymburner – [email protected] lel law enforcement personnel concerns me. Alberta Sheriffs are now armed and so are of- Responding to alarm calls in my early years, ficers with that rather ungainly named South GENERAL MANAGER I recall the ‘key holder’ security car drivers Coast British Columbia Transportation Au- Mary K. Lymburner – [email protected] always having a gun on their hip. I always thority Police Service, (or the “SCABTAPS” SENIOR EDITOR felt just a little safer knowing this. for short). These agencies, like Parliament Mark Reesor – [email protected] The guns gradually disappeared. -

AN ANALYSIS of WILDFIRE IMPACTS on CLIMATE CHANGE By

AN ANALYSIS OF WILDFIRE IMPACTS ON CLIMATE CHANGE By: Taylor Gilson Mentor: Dr. Elaine Fagner 1 Abstract Abstract: The western United States (U.S.). has recently seen an increase in wildfires that destroyed communities and lives. This researcher seeks to examine the impact of wildfires on climate change by examining recent studies on air quality and air emissions produced by wildfires, and their impact on climate change. Wildfires cause temporary large increases in outdoor airborne particles, such as particulate matter 2.5 (PM 2.5) and particulate matter 10(PM 10). Large wildfires can increase air pollution over thousands of square kilometers (Berkley University, 2021). The researcher will be conducting this research by analyzing PM found in the atmosphere, as well as analyzing air quality reports in the Southwestern portion of the U.S. The focus of this study is to examine the air emissions after wildfires have occurred in Yosemite National Park; and the research analysis will help provide the scientific community with additional data to understand the severity of wildfires and their impacts on climate change. Project Overview and Hypothesis This study examines the air quality from prior wildfires in Yosemite National Park. This research effort will help provide additional data for the scientific community and local, state, and federal agencies to better mitigate harmful levels of PM in the atmosphere caused by forest fires. The researcher hypothesizes that elevated PM levels in the Yosemite National Park region correlate with wildfires that are caused by natural sources such as lightning strikes and droughts. Introduction The researcher will seek to prove the linkage between wildfires and PM. -

Community Informatics in Chongqing: a Case Study of the Real-Name and ID Requirement Policy in the Chinese Railway System

Community Informatics in Chongqing: A Case Study of the Real-Name and ID Requirement Policy in the Chinese Railway System Huo Ran 霍然 and Wei Qunyi 魏群义 Abstract This study discusses strategies for narrowing the digital divide by examining the real-name and ID requirement policy that governs online purchases of train tickets in China. Using a case study, the authors of this study asks what factors influence online ticket pur- chasing by railway passengers and examines how Chinese public libraries offer online ticket-purchasing assistance as a strategy for bridging the digital divide. Deploying both quantitative and quali- tative methods—including questionnaires and semistructured in- terviews—the authors found that four factors—gender, age, social status, and privacy concerns—were most important in influencing passengers’ online ticket purchasing, and that Chinese public librar- ies do facilitate access to the digital world. Introduction Over the past two decades, rail travel—especially between urban and ru- ral areas—has grown tremendously in China. This is in part because so many people have left home to pursue employment or higher education. Travel increases especially during the summer holidays and around Chi- nese New Year 春节 and peaks around the Lunar New Year. The period around the Chinese New Year usually begins 15 days before this turn of the year and lasts for about forty days in total (“Chunyun,” 2012). The railroad sees an extremely high traffic load during this period. Annually, approximately three billion passengers travel between China’s provinces during this time—possibly a world record. STNN 星岛环球网 reported that in the two weeks of the Chunyun 春运 period in 2008, the number of passenger journeys exceeded 22 billion.