A Chronicle of Learning: Voicing the Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About Endgame

IN ASSOCIATION WITH BLINDER FILMS presents in coproduction with UMEDIA in association with FÍS ÉIREANN / SCREEN IRELAND, INEVITABLE PICTURES and EPIC PICTURES GROUP THE HAUNTINGS BEGIN IN THEATERS MARCH, 2020 Written and Directed by MIKE AHERN & ENDA LOUGHMAN Starring Maeve Higgins, Barry Ward, Risteárd Cooper, Jamie Beamish, Terri Chandler With Will Forte And Claudia O’Doherty 93 min. – Ireland / Belgium – MPAA Rating: R WEBSITE: www.CrankedUpFilms.com/ExtraOrdinary / http://rosesdrivingschool.com/ SOCIAL MEDIA: Facebook - Twitter - Instagram HASHTAG: #ExtraOrdinary #ChristianWinterComeback #CosmicWoman #EverydayHauntings STILLS/NOTES: Link TRAILER: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1TvL5ZL6Sc For additional information please contact: New York: Leigh Wolfson: [email protected]: 212.373.6149 Nina Baron: [email protected] – 212.272.6150 Los Angeles: Margaret Gordon: [email protected] – 310.854.4726 Emily Maroon – [email protected] – 310.854.3289 Field: Sara Blue - [email protected] - 303-955-8854 1 LOGLINE Rose, a mostly sweet & mostly lonely Irish small-town driving instructor, must use her supernatural talents to save the daughter of Martin (also mostly sweet & lonely) from a washed-up rock star who is using her in a Satanic pact to reignite his fame. SHORT SYNOPSIS Rose, a sweet, lonely driving instructor in rural Ireland, is gifted with supernatural abilities. Rose has a love/hate relationship with her ‘talents’ & tries to ignore the constant spirit related requests from locals - to exorcise possessed rubbish bins or haunted gravel. But! Christian Winter, a washed up, one-hit-wonder rock star, has made a pact with the devil for a return to greatness! He puts a spell on a local teenager- making her levitate. -

Mapping the Aesthetical-Political Sonic, Master Thesis, © March 2017 Supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof

Universität für Künstlerische und Industrielle Gestaltung Linz Institut für Medien Interface Culture SOUNDSREVOLTING:MAPPINGTHE AESTHETICAL-POLITICALSONIC oliver lehner Master Thesis MA supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof. Dr. date of approbation: March 2017 signature (supervisor): Linz, 2017 Oliver Lehner: Sounds Revolting: Mapping the Aesthetical-Political Sonic, Master Thesis, © March 2017 supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof. Dr. location: Linz ABSTRACT I demand change. As a creator of sound art, I wanted to know what it can do. I tried to find out about the potential field in the overlap between a political aesthetic and a political sonic, between an artis- tic activism and sonic war machines. My point of entry was Steve Goodman’s Sonic Warfare. From there, trajectories unfolded through sonic architectures into an activist philosophy in interactive art. Sonic weapon technology and contemporary sound art practices define a frame for my works. In the end, I could only hint at sonic agents for change. iii CONTENTS i thesis 1 1 introduction 3 1.1 Why sound matters (to me) . 3 1.2 Listening for “New Weapons” . 4 1.3 Sounds of War . 5 1.4 Aesthetics and Politics . 6 2 acoustic weapons 11 2.1 On “Non-lethal” Weapons (NLW) . 11 2.2 A brief history of weaponized sound . 14 2.3 Sonic Battleground Europe . 19 2.4 Civil Sonic Weapons and Counter Measures . 20 3 the art of (sonic) war 23 3.1 Advanced Hyperstition: Goodman’s work after Sonic Warfare . 23 3.2 Artistic Sonic War Machines . 26 3.3 Ultrasound Art and Micropolitics of Frequency . 31 4 the search for sound artivism 37 4.1 Art and Activism . -

Flying High Radio Show Playlists

Flying High Radio Show Playlist 2020 30 December 2020 i_o - Castles In The Sky (Extended Mix) Craig Connelly & Alex Holmes - Anything Like You (Daxson Extended Remix) MaRLo & HALIENE - Say Hello (Darren Porter Radio Edit) David Forbes & Susie Ledge - Silent Waves BT,Matt Fax, Nation Of One - Walk Into The Water Iain M & Deirdre McLaughlin - Eternally (Sneijder Extended Remix) Seawayz & Sharon Valerona - By My Side( Extended Mix) Andrew Rayel & Olivia Sebastianelli - Everything Everything (Cosmic Gate Remix) Illitheas & Pedro del Mar With Tiff Lacey - Lightning (Extended Mix) Protoculture & Diana Miro - Seconds Robbie Seed,Digital Vision,Caitlin Potter - Come Back Home (Radio Mix) DT8 & Project & Lustral - On My Own (Last Soldier Remix) Teddy Beats Ft. Mon RovÎa - Waste Some Time Marcus Santoro & Lauren L'aimant - Give Into You LTN & Christina Novelli - I'd Go Back (R.I.B & Seven24 & Eugene Cortez Remix) ©2009-2020 George Jopling https://djgj.co.uk Flying High Radio Show Playlist 2020 23 December 2020 LTN & Christina Novelli - I'd Go Back (Rinaly Extended Remix) Rezwan Khan & Hidden Tigress - Racing To Somewhere (Extended Mix) Susana - Dark Side of The Moon (Ferry Tayle Extended Mix) Tycoos & Jan Johnston - The Landslide (Extended Mix) Robert Nickson With Thea Riley - Feed My Soul (Extended Club Mix) Will Atkinson With Harry Roke - Burning Out Will Atkinson With Cari Golden - Cigarettes & Kerosene Will Atkinson With Perplexer - Acid Folk (Will Atkinson Last King of Scotland Remix) Billy Gillies - Closed Eyes (Extended Mix) Alessandra Roncone - What Makes You Feel Alive (Extended Mix) Nord Horizon - Take My Hand (Extended Mix) Dim3nsion - Outstanding Armin van Buuren Ft. Duncan Laurence - Feel Something Jes & Oliver Smith - Don't Let It End (Accoustic) 16 December 2020 James Kitcher, Adam Taylor & Susie Ledge - Come In From The Cold (Extended Mix) Ana Criado - In A Thousand Skies (Dan Stone Extended Mix) BiXX - Trance At The Opera (Extended Mix) Miyuki Ft. -

Amerikan Movies Draft1.7

AMERIKAN MOVIES 1 AMERICAN MOVIES Table of contents The Parts that Make up the Whole, Some thoughts on the work of The Speculative Archive/Julia Meltzer and David Thorne by Pablo de Ocampo - 3 Frequencies: an interview with Jason Boughton - 6 Taking to the Periphery - 17 by Andrea Picard Light Waves and their Uses - 21 by David Dinnell David Gatten talk - 23 Hand Cranked: a Conversation with Filmmaker Lee Krist by Alex Mackenzie - 30 Milk and Juice: An unfinished text to the artist I wish I’d met before starting psychoanalysis by Deirdre Logue - 38 Experience Torn to Shreds/Experiments From the Granary, Vincent Grenier, A Retrospective by Mike Cartmell - 40 What is Felt Cannot be Forgotten: an interview with Deborah Stratman interview - 46 George Kuchar’s Videos: Excrements of time by Steve Reinke- 58 Jennifer Reeves at Cinemateque Ontatio, fall 2006 – 64 An Interview with Robert Todd – 72 Long Live Experimental: and Interview with Julie Murray - 94 An Interview with Martha Colburn – 109 David Dinnell’s Midden – 118 Dani Leventhal by Steve Reinke - 120 Editor: Mike Hoolboom Notes on 4 Movies by Dani Leventhal - 121 Design by Mike Evans 2 The parts that make up the whole Some thoughts on the work of The Speculative Archive/Julia Meltzer and David Thorne by Pablo de Ocampo Since 1999 Julia Meltzer and David Thorne “the truth” is a means by which to emphasize have been collaborating under the name The the often loose and uncertain nature of the facts Speculative Archive. Though their output they are working with. Meltzer and Thorne’s includes installations, texts, and photographs, process is heavily rooted in an intensive the bulk of their work has been in the production investigation of documents—government texts, of single channel video documentaries. -

Experimental Sound & Radio

,!7IA2G2-hdbdaa!:t;K;k;K;k Art weiss, making and criticism have focused experimental mainly on the visual media. This book, which orig- inally appeared as a special issue of TDR/The Drama Review, explores the myriad aesthetic, cultural, and experi- editor mental possibilities of radiophony and sound art. Taking the approach that there is no single entity that constitutes “radio,” but rather a multitude of radios, the essays explore various aspects of its apparatus, practice, forms, and utopias. The approaches include historical, 0-262-73130-4 Jean Wilcox jacket design by political, popular cultural, archeological, semiotic, and feminist. Topics include the formal properties of radiophony, the disembodiment of the radiophonic voice, aesthetic implications of psychopathology, gender differences in broad- experimental sound and radio cast musical voices and in narrative radio, erotic fantasy, and radio as an http://mitpress.mit.edu Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142 Massachusetts Institute of Technology The MIT Press electronic memento mori. The book includes new pieces by Allen S. Weiss and on the origins of sound recording, by Brandon LaBelle on contemporary Japanese noise music, and by Fred Moten on the ideology and aesthetics of jazz. Allen S. Weiss is a member of the Performance Studies and Cinema Studies Faculties at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. TDR Books Richard Schechner, series editor experimental edited by allen s. weiss #583606 5/17/01 and edited edited by allen s. weiss Experimental Sound & Radio TDR Books Richard Schechner, series editor Puppets, Masks, and Performing Objects, edited by John Bell Experimental Sound & Radio, edited by Allen S. -

The Korean Diaspora

HAUNTING the Korean Diaspora HAUNTING the Korean Diaspora Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War Grace M. Cho UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS Minneapolis • London The University of Minnesota Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance provided for the publication of this book from the Office of the Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences at College of Staten Island–City University of New York. A portion of chapter 4 was published as “Prostituted and Vulnerable Bodies,” in Gendered Bodies: Feminist Perspectives, ed. Judith Lorber and Lisa Jean Moore (Cary, N.C.: Roxbury Publishing, 2007), 210–14; reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc. Portions of chapters 4 and 5 have been previously published as “Diaspora of Camp - town: The Forgotten War’s Monstrous Family,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 34, nos. 1–2 (2006): 309–31. A shorter version of chapter 6 was published as “Voices from the Teum: Synesthetic Trauma and the Ghosts of Korean Diaspora,” in The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social, ed. Patricia Clough with Jean Halley (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2007), 151–69. Portions of chapter 6 were published by Sage Publications as Grace M. Cho and Hosu Kim, “Dreaming in Tongues,” Qualitative Inquiry 11, no. 3 (2005): 445–57, and as Grace M. Cho, “Murmurs in the Storytelling Machine,” Cultural Studies—Critical Methodologies 4, no. 4 (2004): 426–32. Portions of chapter 6 have been performed in “6.25 History beneath the Skin,” a performance art piece in Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War.” In chapter 2, the poem “Cheju Do” by Yong Yuk appears courtesy of the author. -

2019 27Th Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog

2019 27th Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog Poets House | 10 River Terrace | New York, NY 10282 | poetshouse.org ELCOME to the 2019 Poets House Showcase, our annual, all-inclusive exhibition of the most recent poetry books, chapbooks, broadsides, artists’ books, and multimedia works published in the United States and abroad. This year marks the 27th anniversary of the Poets House Showcase and features over 3,300 books from more than 800 different presses and publishers. For 27 years, the Showcase has helped to keep our collection Wcurrent and relevant, building one of the most extensive collections of poetry in our nation—an expansive record of the poetry of our time, freely available and open to all. Building the Exhibit and the Poets House Library Collection Every year, Poets House invites poets and publishers to participate in the annual Showcase by donating copies of poetry titles released since January of the previous year. This year’s exhibit highlights poetry titles published in 2018 and the first part of 2019. Books have been contributed by the entire poetry community, from the publishers who send on their titles as they’re released, to the poets who mail us signed copies of their newest books, to library visitors donating books when they visit us. Every newly published book is welcomed, appreciated, and featured in the Showcase. The Poets House Showcase is the mechanism through which we build our library: a comprehensive, inclusive collection of over 70,000 poetry works, all free and open to the public. To make it as extensive as possible, we reach out to as many poetry communities and producers as we can, bringing together poetic voices of all kinds to meet the different needs and interests of our many library patrons. -

2016-Program-Book-Corrected.Pdf

A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music that brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and with partners in venues throughout the city. The second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, taking place May 23–June 11, 2016, features diverse programs — ranging from solo works and a chamber opera to large scale symphonies — by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American; presents some of the country’s top music schools and youth choruses; and expands to more New York City neighborhoods. A range of events and activities has been created to engender an ongoing dialogue among artists, composers, and audience members. Partners in the 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL include National Sawdust; 92nd Street Y; Aspen Music Festival and School; Interlochen Center for the Arts; League of Composers/ISCM; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; LUCERNE FESTIVAL; MetLiveArts; New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; WQXR’s Q2 Music; and Yale School of Music. Major support for the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, and The Francis Goelet Fund. Additional funding is provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation and Honey M. Kurtz. NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 5-7, 2016 JUNE 13-19, 2016 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 LOCATIONS 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 7 COMMITTEE & STAFF 10 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 11 INSTALLATIONS 88 PRESENTATIONS 90 COMPOSERS 92 PERFORMERS 141 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA THE AMPHION FOUNDATION DIRECTOR’S LOCATIONS WELCOME NATIONAL SAWDUST 80 North Sixth Street Brooklyn, NY 11249 Welcome to NYCEMF 2016! Corner of Sixth Street and Wythe Avenue. -

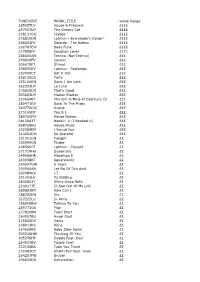

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 285057LV

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 285057LV House & Pressure ££££ 297057LM The Groovy Cat ££££ 298131GQ Jaydee ££££ 276810DN Latmun - Everybody's Dancin' ££££ 268301FV Solardo - The Aztecs ££££ 292787EW Body Funk ££££ 277998FP Egyptian Lover ££££ 286605AN Techno (Not Techno) £££ 276810FV Cosmic £££ 306678FT Strand £££ 296595EV Latmun - Footsteps £££ 252459CT Set It Out £££ 292130GU Party £££ 255100KN Sorry I Am Late £££ 262293LN La Luna £££ 276810DQ That's Good £££ 303663LM Master Blaster £££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Ch £££ 280471KV Back To The Music £££ 323770CW Sueno £££ 273165DT You & I £££ 289765FN House Nation £££ 0412043T Needin' U (I Needed U) £££ 268756KU House Music £££ 292389EM I Found You £££ 314202DM So Grateful £££ 131751GN Tonight ££ 130999GN Finder ££ 296595CT Latmun - Piquant ££ 271719HU Saxomatic ££ 249988HR Moorthon Ii ££ 263938BT Aguardiente ££ 250247GW 9 Years ££ 294966AN Let Go Of This Acid ££ 292489KV 17 ££ 291041LV Ya Kidding ££ 3635852T Shiny Disco Balls ££ 2240177E In And Out Of My Life ££ 269881EM How Can I ££ 188782KN Xtc ££ 327225LU In Arms ££ 156808BW Talking To You ££ 289773GU Play ££ 277820BN False Start ££ 264557BU Angel Dust ££ 215602DR Veins ££ 238913KS Nana ££ 224609BS Baby Slow Down ££ 300216HW Thinking Of You ££ 305278HT Desole Feat. Davi ££ 264557BV Twiple Fwet ££ 232106BS Take You There ££ 272083CP Shakti Pan Feat. Sven ££ 254207FW Bruzer ££ 296650DR Satisfaction ££ 261261AU Burning ££ 2302584E Atlantis ££ 036282DT Don't Stop ££ 309979LN The Tribute ££ 215879HU Devil In Me ££ 290470BR Kubrick -

Final Nominations List

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 61st Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year October 1, 2017 through September 30, 2018 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 8. THE MIDDLE Record Of The Year Zedd, Maren Morris & Grey Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Grey, Monsters & Strangerz & Zedd, producers; Grey, Tom and/or Mixer(s) and mastering engineer(s), if other than the artist. Norris, Ryan Shanahan & Zedd, engineers/mixers; Mike Marsh, mastering engineer 1. I LIKE IT Cardi B, Bad Bunny & J Balvin Invincible, JWhiteDidIt, Craig Kallman & Tainy, producers; Leslie Brathwaite, Kuk Harrell & Evan LaRay, engineers/mixers; Colin Leonard, mastering engineer 2. THE JOKE Brandi Carlile Dave Cobb & Shooter Jennings, producers; Tom Elmhirst & Eddie Spear, engineers/mixers; Pete Lyman, mastering engineer 3. THIS IS AMERICA Childish Gambino Donald Glover & Ludwig Göransson, producers; Derek “MixedByAli” Ali, Riley Mackin & Shaan Singh, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer 4. GOD'S PLAN Drake Boi-1Da, Cardo & Young Exclusive, producers; Noel Cadastre, Noel "Gadget" Campbell & Noah Shebib, engineers/mixers; Chris Athens, mastering engineer 5. SHALLOW Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper Lady Gaga & Benjamin Rice, producers; Brandon Bost & Tom Elmhirst, engineers/mixers; Randy Merrill, mastering engineer 6. ALL THE STARS Kendrick Lamar & SZA Al Shux & Sounwave, producers; Sam Ricci & Matt Schaeffer, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer 7. ROCKSTAR Post Malone Featuring 21 Savage Louis Bell & Tank God, producers; Louis Bell, Lorenzo Cardona, Manny Marroquin & Ethan Stevens, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer © The Recording Academy 2018 - all rights reserved 1 Not for copy or distribution 61st Finals - Press List General Field Category 2 8. -

Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice

Lipsynching: Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice Merrie Snell Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Cultures April 2015 Abstract This thesis is an exploration and problematization of the practice of lipsynching to pre- recorded song in both professional and vernacular contexts, covering over a century of diverse artistic practices from early sound cinema through to the current popularity of vernacular internet lipsynching videos. This thesis examines the different ways in which the practice provides a locus for discussion about musical authenticity, challenging as well as re-confirming attitudes towards how technologically-mediated audio-visual practices represent musical performance as authentic or otherwise. It also investigates the phenomenon in relation to the changes in our relationship to musical performance as a result of the ubiquity of recorded music in our social and private environments, and the uses to which we put music in our everyday lives. This involves examining the meanings that emerge when a singing voice is set free from the necessity of inhabiting an originating body, and the ways in which under certain conditions, as consumers of recorded song, we draw on our own embodiment to imagine “the disembodied”. The main goal of the thesis is to show, through the study of lipsynching, an understanding of how we listen to, respond to, and use recorded music, not only as a commodity to be consumed but as a culturally-sophisticated and complex means of identification, a site of projection, introjection, and habitation, -

Playback Singers of Bollywood and Hollywood

ILLUSION AND REALITY: PLAYBACK SINGERS OF BOLLYWOOD AND HOLLYWOOD By MYRNA JUNE LAYTON Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject MUSICOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA. SUPERVISOR: PROF. M. DUBY JANUARY 2013 Student number: 4202027-1 I declare that ILLUSION AND REALITY: PLAYBACK SINGERS OF BOLLYWOOD AND HOLLYWOOD is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. SIGNATURE DATE (MRS M LAYTON) Preface I would like to thank the two supervisors who worked with me at UNISA, Marie Jorritsma who got me started on my reading and writing, and Marc Duby, who saw me through to the end. Marni Nixon was most helpful to me, willing to talk with me and discuss her experiences recording songs for Hollywood studios. It was much more difficult to locate people who work in the Bollywood film industry, but two people were helpful and willing to talk to me; Craig Pruess and Deepa Nair have been very gracious about corresponding with me via email. Lastly, putting the whole document together, which seemed an overwhelming chore, was made much easier because of the expert formatting and editing of my daughter Nancy Heiss, sometimes assisted by her husband Andrew Heiss. Joe Bonyata, a good friend who also happens to be an editor and publisher, did a final read-through to look for small details I might have missed, and of course, he found plenty. For this I am grateful.