Approaching the Debtera in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-Present)

" Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-present) By Mezmur Tsegaye Advisor Teklehaymanot Gebresilassie (Ph.D) CiO :t \l'- ~ A Research Presented to the School of Graduate Study Addis Ababa University In Patiial FulfI llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Ali in Tourism and Development June20 11 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES (; INSTITUE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES (IDS) Title Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-present). By Mezmur Tsegayey '. Tourism and Development APPROVED BY THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS: SIGNATURE Dr. Belay Simane CENTER HEAD /~~ ~~~ ??:~;~ Dr. Teclehaimanot G/Selassie ADVISOR Ato Tsegaye Berha INTERNAL EXAMINER 1"\3 l::t - . ;2.0 1\ GLOSSARY Abugida Simple scheme under which children are taught reading and writing more quickly Abymerged Moderately fast type of singing with sitsrum, drum, and prayer staff C' Aquaqaum chanting integrated with sistrum, drum and prayer staff Araray melancholic note often chanted on somber moments Astemihro an integral element of Degua Beluy Old Testament Debtera general term given to all those who have completed school of the church Ezi affective tone suggesting intimation and tenderness Fasica an integral element of Degua that serves during Easter season Fidel Amharic alphabet that are read sideways and downwards by children to grasp the idea of reading. Fithanegest the book of the lows of kings which deal with secular and ecclesiastical lows Ge 'ez dry and devoid of sweet melody. Gibre-diquna the functions of deacon in the liturgy. Gibre-qissina the functions of a priest in the liturgy. -

Journal of Three Years' Residence in Abyssinia

Journal of three years' residence in Abyssinia http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.sip100045 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Journal of three years' residence in Abyssinia Author/Creator Gobat, Samuel Date 1850 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Horn of Africa, Ethiopia, Lalibela;Axum, Eritrea Source Smithsonian Institution Libraries, DT377 .G574X/916.3 G574X Description Biography of Mr. Gobat. Introduction. Part I. Abyssinia and its Inhabitants. Part II. Historical Sketch of the Abyssinian Church. Chapter I: Mr. Gobat's journey from Adegrate to Gondar. Conversations, by the way, with fellow travelers. -

The Teaching-Learning Processes in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church

The Teaching-learning Processes in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Accreditation Schools of Music (Zema Bets): The Cases of Bethlehem, Zur Aba and Gondar Baeta Mariam Churches SELAMSEW DEBASHU A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE CENTER FORAFRICAN AND ORIENTAL STUDIES PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS IN AFRICAN STUDIES (AFRICAN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY AND CULTURAL STUDIES) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia February, 2017 i The Teaching-learning Processes in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Accreditation Schools of Music (Zema Bets): The Cases of Bethlehem, Zur Aba and Gondar Baeta Mariam Churches SELAMSEW DEBASHU A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE CENTER FORAFRICAN AND ORIENTAL STUDIES PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS IN AFRICAN STUDIES (AFRICAN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY AND CULTURAL STUDIES) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia February, 2017 Addis Ababa University School of Graduate studies ii This is to accredit that the thesis prepared by Selamsew Debashu, entitled: The Teaching- learning Processes in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Accreditation Schools of Music (Zema Bets): The Cases of Bethlehem, Zur Aba and Gondar Baeta Mariam Churches, and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in African Studies (African Intellectual History and Cultural Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted stands with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the Examining committee Examiner_______________________signature___________________date______________ Examiner_______________________signature___________________date______________ Advisor_______________________signature__________________date_________________ iii Acknowledgment I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Samuel Tefera for his invaluable insights and advises offered during the entire period of this research project. -

Features of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Clergy

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 7, 1998, 1, 87–104 FEATURES OF THE ETHIOPIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE CLERGY Getnet TAMENE Institute of Oriental and African Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has significantly declined since the disruption of her ally the so-called “Solomonic Line” in 1974, when the last monarch was overthrown; nevertheless, she still exerts strong influence on the lives of millions even without the support of her ally, the State. Neither the divorce of Church-State relations, which culminated with the end of the monarchy and introduction of Communist ideology in the 1970s, nor the trends of pluralistic democracy-based currently flourishing Independent Churches, could remove away her influence in the country. In fact, these events have threatened the position of this archaic Church and made questionable the possiblity of her perpetuation, as can be well observed at the turn of the century. 1. Introduction Features of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Clergy is a topic de- signed to give a historical overview of the Church, ecclesiastical establishment and the process undertaken to develop Orthodox Christianity within the country. The paper gives an analysis of one part of my on-going Ph.D. dissertation on the history of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, in relation to the country’s state sys- tems. 1.1 Definition of the Terms Orthodox Church and the Clergy The terms Orthodox Church and the Clergy, in this text, are terms inter- waved to refer to one type of Christian religious institution (the Orthodox Church) and the group of ordained persons (clergy) who minister in the Church. -

Alexandra E.S. Antohin Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of The

EXPRESSIONS OF SACRED PROMISE: RITUAL AND DEVOTION IN ETHIOPIAN ORTHODOX PRAXIS Alexandra E.S. Antohin Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London 2014 I, Alexandra E.S. Antohin, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 2 ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the notion of sacred promise, a grounded devotional category for Ethiopian Orthodox Christians. It is based on ethnographic research among urban parishes seeking to gather the often dispersed memberships of local Orthodox communities in Dessie, a city of a quarter million residents in north-central Ethiopia. The central thesis contends that the spaces and methods of engagement by Ethiopian Orthodox Christians are organized by the internal dynamics of archetypal promises. I consider the wide spectrum of social and ritual activities contained within the domain of “church” to be consistent with a developed socio-theological genre of “covenant”. Covenant is narratively defined as a dialogic of bestowal and responsibility and it is also expressed in performative, material, and associative dimensions. Starting from an investigation of the liturgical praxis of temesgen (the ethic of thanksgiving), each chapter explores variations of covenant: as unifying events of human/divine manifestation (e.g. feast days); as the honour of obligation within individual stances of paying respect on an interpersonal and meta-relational level, at church and during visits to mourning houses; and through customs of reciprocity by confraternities and the blessings such practices confer on the givers and receivers. -

Local History of Ethiopia Aka - Alyume © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia Aka - Alyume © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) HC... Aka (centre in 1964 of Bitta sub-district) 07/35? [Ad] HFC14 Akab Workei (Aqab Uorchei) 13°42'/36°58' 877 m 13/36 [+ Gz] akabe saat: aqabe sä'at (Geez?) "Guardian of the Hour", at least from the 15th century a churchman attached to the palace and also in the 18th century "the first religious officer at the palace"; akkabi (aqqabi) (A) guardian, custodian; (T) collector, convener HFE50 Akabe Saat (Acab Saat, Aqab Se'at, Akabie Se'at) 14/38 [+ Gu Ad Gz] (mountain & place) 14°06'/38°30' 2385 m (sub-district & its centre in 1964) 1930s Towards midday on 29 February 1936 the 'April 21st' Division, at the head of a long column, reached the heights of Acab Saat without encountering the enemy, and consolidated its position there. [Badoglio (Eng.ed.)1937 p 115] On 29 February as above, Blackshirt and voluntary soldier Francesco Battista fought during four hours at Akabe Saat before he was killed. He was posthumously honoured with a gold medal. [G Puglisi, Chi è? .., Asmara 1952] 1980s According to government reports TPLF forces deployed in the May Brazio-Aqab Se'at front around 8-9 February 1989 were estimated to be three divisions, two heavy weapon companies and one division on reserve. [12th Int. Conf. of Ethiopian Studies 1994] HED98 Akabet (Ak'abet, Aqabet) 11°44'/38°17' 3229 m 11/38 [Gz q] HDM31 Akabido 09°21'/39°30' 2952 m 09/39 [Gz] akabo: Akebo Oromo penetrated into Gojjam and were attacked by Emperor Fasiledes in 1649-50 ?? Akabo (Accabo) (mountain saddle) c1900 m ../. -

The Shade of the Divine Approaching the Sacred in an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Community

London School of Economics and Political Science The Shade of the Divine Approaching the Sacred in an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Community Tom Boylston A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 85956 words. 2 Abstract The dissertation is a study of the religious lives of Orthodox Christians in a semi‐ rural, coffee‐producing community on the shores of Lake Tana in northwest Ethiopia. Its thesis is that mediation in Ethiopian Orthodoxy – how things, substances, and people act as go‐betweens and enable connections between people and other people, the lived environment, saints, angels, and God – is characterised by an animating tension between commensality or shared substance, on the one hand, and hierarchical principles on the other. This tension pertains to long‐standing debates in the study of Christianity about the divide between the created world and the Kingdom of Heaven. -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Intelligible Tolerance, Ambiguous Tensions, Antagonistic Revelations: Patterns of Muslim-Christian Coexistence in Orthodox Christian Majority Ethiopia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by John Christopher Dulin Committee in charge: Professor Suzanne Brenner, Chair Professor Joel Robbins, Co-Chair Professor Donald Donham Professor John Evans Professor Rupert Stasch 2016 Copyright John Christopher Dulin, 2016 All rights reserved The Dissertation of John Christopher Dulin is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication in microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……….....……………………..………………………………….………iii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………iv List of Figures……...…………………………………………………………...………...vi Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………....vii Vita…………...…….……………………………………………………………...….…...x Abstract…………………………………………………………………………...………xi Introduction Muslim-Christian Relations in Northwest Ethiopia and Anthropological Theory…………..…………………………………………………………………..……..1 Chapter 1 Muslims and Christians in Gondaré Time and Space: Divergent Historical Imaginaries and SpatioTemporal Valences………..............................................................……….....35 Chapter 2 Redemptive Ritual Centers, Orthodox Branches and Religious Others…………………80 Chapter 3 The Blessings and Discontents of the Sufi Tree……………………...………………...120 -

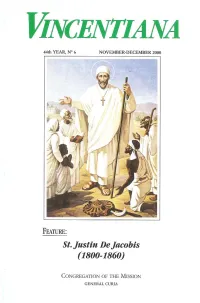

Devotion to St. Justin De Jacobis in Eritrea and Ethiopia

Vincentiana Volume 44 Number 6 Vol. 44, No. 6 Article 9 11-2000 Devotion to St. Justin de Jacobis in Eritrea and Ethiopia Iyob Ghebresellasie C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ghebresellasie, Iyob C.M. (2000) "Devotion to St. Justin de Jacobis in Eritrea and Ethiopia," Vincentiana: Vol. 44 : No. 6 , Article 9. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol44/iss6/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Devotion to St. Justin de Jacobis in Eritrea1 and Ethiopia2 By Iyob Ghebresellasie, C.M. Province of Eritrea In speaking about devotion to St. Justin I should say in advance that this refers in a special way to the Catholics in Eritrea and in some areas of Ethiopia. As is well known, St. Justin's apostolate was mainly in the country which at one time was known as Abyssinia, but which today is two countries, Eritrea and Ethiopia. 1. Christianity before St. Justin's evangelization The first Christian seed was planted along the Eritrean coast in the first century,3 and in time, by crossing the Eritrean plateau, it spread into northern Ethiopia. From the beginning of the fourth century until the 18th, before St. -

Download Thesis

Christological Conceptions within the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewhado Church (EOTC) and the Ethiopian Evangelical Churches (EEC): Possible Christological-Soteriological Unity between the EOTC-EEC By Esckinder Taddesse Woldegebrial A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At The South African Theological Seminary Date December 2013 Structure and Chapter Outline Chapter one: Introduction/Problem………………………………………………3-40 Chapter Two: Christological sense of the New Testament Texts……………………………………………………………………………….41-134 Chapter Three: Christological Thought Progressions in Church History……………………………………………………………………………135-169 Chapter Four: EOTC and EEC Christological Literatures and Traditions………………………………………………………………………...170-201 Chapter Five: Reflective Epistemological Critique………………………….202-242 Chapter Six: Moving Towards Unity..........................................................243-289 Chapter Seven: Conclusion……………….………………………………… 290-298 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………299-319 2 Chapter One I Introduction/Problem Christological debates have been all through the history of the church. Different exegetes responded differently towards the issue of Christology. All the responses seem to be responses for the doctrinal/theological uncertainties within their own historical context. For instance, the responses of Nestorius and or Eutyches or Cyril or Chalcedon with the philosophical difficulties of the “two natures in one person” led to a hypostatic controversy of the human and the divine or the vice versa. Before we step into the detailed discussions of our own quests, let’s re-enforce the gist of this research by reviewing a little bit of Christological quests from the past. In practice, trying to examine all enigmas of the past is an unfeasible task. Therefore we would be selective in our approach of dealing with seeming puzzles of the past. For this very purpose this research will mainly focus on Nestorius, Euthyches, Cyril and Leo. -

VT-2000-06-ENG-ALL.Pdf

HOLY SEE Appointments The Holy Father John Paul II has raised the Apostolic Prefecture of Tierradentro to the rank of Apostolic Vicariate, with the same denomination and territorial configuration. Moreover, His Holiness has named Fr. Jorge García Isaza, C.M. as the first Apostolic Vicar of Tierradentro (Colombia), assigning him the Episcopal See of Budua. Until now, Fr. García was Apostolic Prefect of the same Ecclesiastical Circumscription. (L’Osservatore Romano, February 27, 2000, p. 1) The Holy Father John Paul II has named Fr. Cristoforo Palmieri, C.M. Apostolic Administrator of Rrëshen (Albania). Up to the present, he was Diocesan Administrator of this same diocese. (L’Osservatore Romano, March 6-7, 2000, p. 1) The Holy Father John Paul II has named Fr. Anton Stres, C.M. Auxiliary Bishop of Maribor in Slovenia, assigning to him the titular episcopal see of Ptuj. Up to the present, Fr. Stres has been dean of the Theology Faculty of Ljubljana. (L’Osservatore Romano, May 14, 2000, p. 2) Decree On 1 July 2000, in the presence of the Holy Father, was promulgated the decree regarding the heroic virtues of the Servant of God, Marco Antonio Durando, priest of the Congregation of the Mission of St. Vincent de Paul and Founder of the Institute of the Sisters of Jesus of Nazareth, born on 22 May 1801 at Mondovì (Italy) and died on 10 December 1880 at Turin (Italy). (L’Osservatore Romano, July 2, 2000, p. 1) Letter The Holy Father John Paul II wrote to His Excellency Gaston Poulain, Bishop of Périgueux and Sarlat, a letter dated September 8, on the occasion of the fourth centenary of the priestly ordination of St. -

Debre Tabor - Delo Wereda © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia Debre Tabor - Delo wereda © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) Debre Tabor, Mount Tabor of the Bible, (figuratively:) the Transfiguration HEK05 Debre Tabor (Debra T., old name Samara) 11/38 [Gz Pa WO Gu] MS: 11°51'/38°05' = HEK06, 2945 m at the gibbi Gz: 11°51'/38°01' = HEK05, 2706 m Distance 666 km from Addis Abeba. Centre in 1964 of Debre Tabor awraja and Farta wereda and Debre Tabor sub-district. Within a radius of 10 km there are at km 7E Hiruy (Waher, Uaher) (village) 2628 m 8E Amija (Amigia) 10SE Meken Kenia (village) 10SE Semana Giyorgis (S. Ghiorghis) (village) 10SE Amejera Abbo (Ameggera Abbo) (village) 2S Fahart (area) 7SW Grariya Giyorgis (Graria Georgis) (village) 7SW Amba Maryam (A. Mariam) (with church) 6NW Aringo (village) 2515/2574 m 5N Limado (hill) 5?NE Gafat (historical place, cf under its own name) 8NE Guntur (village) ?NE Samara (former ketema) 2706/2782 m ?? Anchim (Anchem) (battle site) ?? Tala Levasi 2558 m Debre Tabor is situated in an amphitheatre of hills. It bears the name of the nearby mountain, which in early medieval times was called Debre Tabor for its resemblance to Mount Tabor in Palestine. On top of the mountain is the Yesus Church, famous for its wood-carvings. The wall paintings are modern. [Jäger 1965 p 75] 1500s The name is known for the first time from the reign of Lebne Dengel, before 1540. 1700s In the last quarter of the 1700s, a man by the name of Ali Gwangul emerged as a powerful figure. He initiated what came to be known as the Yejju dynasty.