Responding to Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy by Mark Diesendorf

Review: Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy By Mark Diesendorf Reviewed by Elery Hamilton-Smith Charles Sturt University, Australia Diesendorf, Mark. Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy . Sydney, NSW: University of New South Wales Press, 2007. 413 pp. ISBN 978-086-8409-733. AU$45.95, paper. This is indeed a timely book. The proliferation of books on world environmental trends, policies and issues means that there are literally thousands of pages clamoring for the attention of those interested. Many of these are simply advocating specific conceptualizations and solutions to one or more of the many global problems. Too many of them either neglect, or are deficient on, critical assessment of the necessary evidence. Diesendorf writes with great clarity, explaining complex issues and ideas without over-simplifying or dumbing down. Essentially, after a basic conceptual review, he critically evaluates eight major strategic directions, either already practiced or commonly proposed and advocated in global policy arenas. Each of these strategies is assessed in terms of the potential resources, current status and action, environmental, health and social impacts, economic and future development potential. Essentially, he concludes that, at least in Australia and probably globally, a combination of efficient energy use, solar hot water, gas, bio-energy, wind power, improved public transport and fuel-efficient vehicles could halve greenhouse emissions within a few decades. But the political will is lacking, and much government policy action serves only to further the production of greenhouse emissions. The large and wealthy fossil fuel industries, including their infrastructural demands such as power stations, transport, urban structure and building standards, are major determinants of governmental expenditure. -

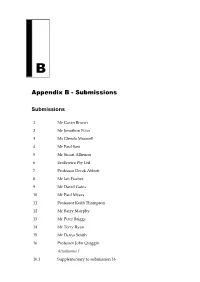

Appendix B: Submissions

B Appendix B - Submissions Submissions 1 Mr Gavin Brown 2 Mr Jonathon Peter 3 Ms Glenda Maxwell 4 Mr Paul Savi 5 Mr Stuart Allinson 6 EcoEnviro Pty Ltd 7 Professor Derek Abbott 8 Mr Ian Fischer 9 Mr David Gates 10 Mr Paul Myers 11 Professor Keith Thompson 12 Mr Barry Murphy 13 Mr Peter Briggs 14 Mr Terry Ryan 15 Mr Denys Smith 16 Professor John Quiggin Attachment 1 16.1 Supplementary to submission 16 190 17 Mr Terje Petersen 18 Mr Allen Tripp 19 Mr Rob Watson-Smith 20 Dr Matthew Gustafson 21 Mr John Hallam 22 Cr Dominic Wy Kanak 23 Mr Ian Bennett 24 Mr Stephen Brown 25 Mr Greig Meyer 26 Mr John Drake 27 Mr Alan Hewett 28 Mr Robert Gishubl 29 ThorCon US 30 Mr Richard Legar and Ms Lyn Allenn 31 Mr Geoff Billard 32 Ms Trish Frail 33 Mr Bruce McDonald 34 Mr Dale Hess 35 Mr Goronwy Price 36 Friends of the Earth Australia 37 Dr Geoffrey Hudson 38 Mr Eric Gribble 39 SMR Nuclear Technology Pty Ltd 40 Mr Gerard Van Hees 41 Dr Ziggy Switkowski AO 42 Mr Allen Biggins 43 Dr Susan Tregeagle 44 Ms Helen Smith APPENDIX B - SUBMISSIONS 191 45 Mr Gregory Wolfe 46 Mr David Allen 47 Mrs Jacqualine McCarroll 48 Mr Mark Fitzsimmons 49 Ms Peggy Fisher 50 Mr Michael Angwin 51 Ms Claudia Tregoning 52 Ms Jenny Lovric 53 Mr Clif Barker 54 Hydricity Systems 55 Mr Stuart McConville 56 Dr Tom Biegler 57 Mr Fred Tropp-Asher 58 Mrs Carmel Laycock 59 Mr Arnaud Coquillard 60 Mr Barrie Hill Attachment 1 Attachment 2 Attachment 3 61 Mr Terry Krieg 62 Mr Dennis Nickell 63 Dr Heiko Timmers 64 Mr Adrian Stephan 64.1 Supplementary to submission 64 65 Mr Wayne Chamley 66 Mr -

Dollars for Death Say No to Uranium Mining & Nuclear Power

Dollars for Death Say No to Uranium Mining & Nuclear Power Jim Green & Others 2 Dollars for Death Contents Preface by Jim Green............................................................................3 Uranium Mining ...................................................................................5 Uranium Mining in Australia by Friends of the Earth, Australia..........................5 In Situ Leach Uranium Mining Far From ‘Benign’ by Gavin Mudd.....................8 How Low Can Australia’s Uranium Export Policy Go? by Jim Green................10 Uranium & Nuclear Weapons Proliferation by Jim Falk & Bill Williams..........13 Nuclear Power ...................................................................................16 Ten Reasons to Say ‘No’ to Nuclear Power in Australia by Friends of the Earth, Australia...................................................................16 How to Make Nuclear Power Safe in Seven Easy Steps! by Friends of the Earth, Australia...................................................................18 Japan: One Year After Fukushima, People Speak Out by Daniel P. Aldrich......20 Nuclear Power & Water Scarcity by Sue Wareham & Jim Green........................23 James Lovelock & the Big Bang by Jim Green......................................................25 Nuclear Waste ....................................................................................28 Nuclear Power: Watt a Waste .............................................................................28 Nuclear Racism .................................................................................31 -

100% Renewable Electricity for South Australia a Background Paper for the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission

100% Renewable Electricity for South Australia A background paper for the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Conservation Council of South Australia June 2015 This report was researched and written by Dr Mark Diesendorf, Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the Institute of Environmental Studies, UNSW Australia, for the Conservation Council of South Australia. Contact email: [email protected] Views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Conservation Council of South Australia. Suggest citation: Diesendorf M (2015) 100% Renewable Electricity for South Australia. Conservation Council of South Australia, Adelaide. 1 2 Contents Executive summary 5 Abbreviations and conversion factor 10 1. Introduction 11 2. Renewable energy resources 12 3. Reliability 12 3.1 Reliability of supply with high penetrations of RE 13 3.2 Reliability of supply with high penetration of nuclear 15 4. Economics 16 4.1 Renewable energy economics 16 4.2 Nuclear energy economics 19 4.3 Comparing costs of renewable and nuclear 21 5. Benefits, risks and safety 21 5.1 Benefits 21 5.2 Risks and safety 23 6. The key challenges and policies for solving them 23 6.1 The key challenges 23 6.2 Targets 24 6.3 Renewable energy incentives 24 6.4 Renewable energy certificates 24 6.5 Reverse auction 25 6.6 Capacity payments for flexible, fast response power stations 25 6.7 Fair feed-in tariffs for small- and medium-scale renewable energy 25 6.8 Fair prices for retail electricity 26 6.9 A new transmission spine 26 6.10 Sea-water pumped hydro 27 7. -

Renewable Electricity Policy for Australia

Renewable electricity policy for Australia Mark Diesendorf Associate Professor, School of Humanities & Languages UNSW Sydney Email: [email protected] November 2018 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any other organisation. Donations to its Research Fund are tax deductible for the donor. Anyone wishing to donate can do so via the website at https://www.tai.org.au or by calling the Institute on 02 6130 0530. -

View, Nuclear Power Plants Provide a Hope Which Coal Plants Cannot

ENERGY SUSTAINABILITY: THE CASE OF PHOTOVOLTAICS Submitted to fulfill the requirements for candidacy as an Honors student in the Environmental Studies Program by Abram Walden Kaplan April, 1985 Oberlin College Please do not quote or distribute without the express permission of the author ----and the Environmental--· . --- Studies -- Program,----- Oberlin--- College.--- - Acknowledgements This proJect has been tremendously challenging and satisfying. It has given me the opportunity to link together my studies in many-- different disciplines, and to show their relevance to one another certainly a crucial facet of Environmental Studies. Four people in particular have invested considerable effort in seeing me through the research and writing process, and I cannot express enough my appreciation for their advice: Gil Heilaender and Larry Buell, my Honors advisors, have given me carefully prescribed doses of constructive feedback and thoughtful criticism. Thia proJect never ran into anything one might call a crisis, and my advisors can take much of the credit for preventing that. The two other maJor influences have been my parents, who have been incredibly patient and encouraging in seeing through the development of some of the themes in this thesis. Harlan Wilson, one of my Honors advisors for the first half of the proJect (until he left for a semester in London) was also very helpful in narrowing my focus and forcing me to think about what it was that I was attempting to do. Michael Kraft, Lucy Jarosz, Bob Tufts, Bob Hilborn, David Orr, Jay HacDaniel, George Lankford, and George Foy read all or part of my thesis in various stages, and offered excellent advice in clarifying and refining my writing. -

The Economic and Institutional Foundations of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change: the Political Economy of Roadmaps to a Sustainable Electricity Future

THE ECONOMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE PARIS AGREEMENT ON CLIMATE CHANGE: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ROADMAPS TO A SUSTAINABLE ELECTRICITY FUTURE Mark Cooper Senior Fellow for Economic Analysis Institute for Energy and the Environment, Vermont Law School Adjunct Fellow, Silicon Flatirons, University of Colorado Abstract Three recent “roadmap” analyses outline routes to a low-carbon economy that model the decarbonization of the electricity sector and the pervasive electrification of the transportation and industrial sectors. Two of these also impose a pollution constraint on electricity resources that rejects the use of nuclear power and fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage. Using independent cost estimates and sequentially “relaxing” the constraints on resource selection, this paper compares the resource costs of the resulting portfolios of assets needed to meet the need for electricity. Reflecting the continuing decline of the cost of renewable resources, the paper supports the claim that the long run costs of the 100% renewable portfolios are not only less than business-as-usual portfolios, but that the “environmental merit order” of asset selection is quite close to the “economic merit order.” Neither fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage nor nuclear power enters the least-cost, low-carbon portfolio. As long as a rigorous least-cost constraint is imposed on decarbonization, the pollution constraint is superfluous. The paper evaluates the Paris Agreement on climate change in light of these findings. The Agreement is described as a progressive, mixed market economic model with a governance structure based on a polycentric, multi-stakeholder approach for management of a common pool resource. -

Submission: Senate Select Committee on Fuel and Energy

Submission to Senate Select Committee on Fuel and Energy www.aph.gov.au/SENATE/committee/fuelenergy_ctte/index.htm [email protected] Submission by: Anti-nuclear & Clean Energy Campaign Friends of the Earth, Australia Contact: Jim Green B.Med.Sci.(Hons.), PhD National nuclear campaigner - Friends of the Earth, Australia 0417 318 368 [email protected] PO Box 222, Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. <www.foe.org.au/anti-nuclear> July 21, 2009 "The nuclear non-proliferation treaty continues to fracture. And there has been little if any progress on nuclear arms reduction – let alone nuclear disarmament." Kevin Rudd 5 July 2007 – Lowy Institute. "[T]he Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty disintegrates before our very eyes … the current non-proliferation regime is fundamentally fracturing. The consequences of the collapse of this regime for Australia are acute, including the outbreak of regional nuclear arms races in South Asia, North East Asia and possibly even South East Asia." Kevin Rudd 19 September 2006 - Sydney Institute. CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Nuclear power and climate change 3. Nuclear power and nuclear weapons 4. Nuclear power and water scarcity 5. Radioactive waste 6. Nuclear accidents 7. Economics of nuclear power 1. INTRODUCTION Friends of the Earth, Australia (FoE) understands that the Select Committee is considering nuclear energy in the context of energy security, hence this submission. While this submission focusses on nuclear power, references to a large and ever-growing number of scientific 'deep cuts' studies - most of which propose a mix of renewables plus concerted energy conservation/efficiency measures - are posted at: www.foe.org.au/anti-nuclear/issues/clean-energy. -

The Eye of the Storm. an Integral Perspective on Sustainable

The Eye of the Storm An Integral Perspective on Sustainable Development and Climate Change Response Christopher Riedy Institute for Sustainable Futures University of Technology, Sydney Thesis submitted for the PhD in Sustainable Futures May 2005 CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP/ORIGINALITY I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate _________________________________________________ Acknowledgements The thesis I present here is the culmination of a long journey that has taken many twists and turns. I have many people to thank for their guidance and support along that journey. My supervisors have each contributed in their own way. Mark Diesendorf, my original supervisor, provided the vision that began the journey and introduced me to academic research. It was Mark’s idea to investigate subsidies to fossil fuel production and consumption in Australia. My initial work on subsidies benefited greatly from Mark’s experience. My second supervisor, Chloe Mason, introduced me to the social sciences and to the rigour required of an academic. The lessons were difficult at the time but valuable in hindsight. Indirectly, Chloe taught me to pursue my own research path. My current supervisor, Professor Stuart White, gave me the freedom to pursue that path and my work flourished under his supervision. -

Renewables Flyer.10.Cdr

The Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy the Clean Energy Future “A plan to cut Queensland's CO2 emissions Cooperation, TREC have released their study into form electricity by 2010” solar thermal energy produced in the worlds' study has found that Australia can readily meet its energy www.wwf.org.au/ourwork/climatechange/Cleanenergyfuture/ deserts in July 2006 www.trecers.net needs from a range of commercially proven fuels and technologies. In the study 2040 time horizon was chosen was released in April 2005. It shows that an alternative 1.The solar energy available in deserts is more than 700 deliberately. It is long enough for almost all existing coal energy mix together with the firm implementation of energy times the present global primary energy consumption. fired energy supply infrastructure and other less energy efficiency measures and policies could economically This is far more than needed to replace fossil fuels. efficient equipment to be fully written off. substitute for the present coal fired power as well as the A scenario that cuts emissions by 50% includes: newly proposed coal fired backup Kogan Creek power 2.Solar thermal power plants can store solar heat and station. ?The energy generated from the combustion of generate solar power according to demand, also at night. natural gas can provide 30% (including The mix would consist of bio-energy, combined cycle and cogeneration) of our electricity by 2040. cogeneration fuelled with coal seam methane and wind 3.Technologies for power production and long-distance power. ?The energy released from biomass from transmission to over 90% of world population are at hand. -

Friends of the Earth Australia May 2005

HOUSE OF rEPRES~NTA~lVES STAND~G COMM~fTLE ON Submission No. 52 i 5 JUN 2U05 INDUSTRY ANflT3ESOURCES Inquiry into the Strategic Importance of Australia’s Uranium Resources The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources Contents: Introduction pg. 2 Comments pg. 4 Summary pg. 27 References pg. 28 Friends of the Earth Australia May 2005 Page 1 of29 Submission to TheHouse of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources Inquiry into the Strategic Importance ofAustralia’s Uranium Resources Introduction This submission has been prepared by the Friends of the Earth Australia Anti Nuclear Campaign. Friends of the Earth is a non-government, non-profit organisation committed to social justice and environmental sustainability. Friends of the Earth is active at local, regional and national levels and is also a member of the Friends of the Earth International network of 71 member groups, one of the worlds largest non-government environmental groupings. Friends of the Earth has been actively engaged on nuclear issues in Australia for over 30 years. Friends of the Earth is committed to phasing out of the nuclear industry based on the premise that it is an unsafe, unwanted and unnecessary impact on both people and the environment. Over 50 years the nuclear industry has failed to deliver it’s promise of safe, clean energy while in reality continued to generate hazardous waste and entrench the threat of nuclear weapons. Friends of the Earth works toward a nuclear free future; opposing major nuclear developments; campaigning for responsible management of waste and presenting clean safe alternatives. -

Averting a Nonproliferation Disaster

Decision Time on the Indian Nuclear Deal: Help Avert a Nonproliferation Disaster August 15, 2008 Federal Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier Federal Foreign Office Auswartiges Amt 11013 Berlin Germany Dear Minister Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier: Your government and other members of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) are being asked to consider the Bush administration’s proposal to exempt India from longstanding NSG guidelines that require comprehensive IAEA safeguards as a condition of supply. As many of us wrote in a January 2008 letter (“Fix the Proposal for Nuclear Cooperation with India” http://legacy.armscontrol.org/pressroom/2008/NSGappeal.asp, India's commitments under the current terms of the proposed arrangement do not justify making far-reaching exceptions to international nonproliferation rules and norms. Contrary to the claims of its advocates, the deal fails to bring India further into conformity with the nonproliferation behavior expected of the member states of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Unlike 178 other countries, India has not signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). It continues to produce fissile material and expand its nuclear arsenal. As one of only three states never to have signed the NPT, it has not made a legally-binding commitment to achieve nuclear disarmament, and it refuses to allow comprehensive, full-scope International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards. Yet the arrangement would give India rights and privileges of civil nuclear trade that have been reserved only for members in good standing under the NPT. It creates a dangerous distinction between "good" proliferators and "bad" proliferators and sends out misleading signals to the international community with regard to NPT norms.