Fahrig L. in Press. Forty Years of Bias in Habitat Fragmentation Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Does Habitat Fragmentation Affect Biodiversity? a Controversial Question at the Coreof Conservation Biology

Biological Conservation xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Editorial How does habitat fragmentation affect biodiversity? A controversial question at the coreof conservation biology Does habitat fragmentation harm biodiversity? For many years, production based in part on concerns about the negative effects of most conservation biologists would say “yes.” It seems intuitive that fragmentation (OMNR, 2002; Fahrig, 2017). fragmentation divides habitats into smaller patches, which support Fahrig (2017) recently argued that the evidence base for these be- fewer species (Haddad et al., 2015). Edge effects further erode the liefs, recommendations, and actions is not as strong as many think, ability of small patches to support some species. This reasoning has largely due to the confounding effects of scale, habitat amount, and been invoked, for example, when interpreting the results of iconic fragmentation. In a separate essay, Fahrig (2018) described the history conservation experiments and studies, such as the large forest frag- of research that led to the current understanding (or misunderstanding) ments experiment in the Brazilian Amazon (Laurance et al., 2011), and regarding the effects of fragmentation on biodiversity. Processes that has been supported by meta-analyses of the findings of fragmentation occur at local patch scales—the scale of the vast majority of fragmen- experiments (Haddad et al., 2015). The negative effects of fragmenta- tation studies—may not be the dominant processes that affect biodi- tion are taught to students in introductory biology, ecology, and con- versity at larger landscape scales. Moreover, in practice, landscapes servation courses and featured in textbooks. -

The Habitat Amount Hypothesis Lenore Fahrig

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2013) 40, 1649–1663 SYNTHESIS Rethinking patch size and isolation effects: the habitat amount hypothesis Lenore Fahrig Geomatics and Landscape Ecology Research ABSTRACT Laboratory (GLEL), Department of Biology, I challenge (1) the assumption that habitat patches are natural units of mea- Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, K1S 5B6, surement for species richness, and (2) the assumption of distinct effects of hab- Canada itat patch size and isolation on species richness. I propose a simpler view of the relationship between habitat distribution and species richness, the ‘habitat amount hypothesis’, and I suggest ways of testing it. The habitat amount hypothesis posits that, for habitat patches in a matrix of non-habitat, the patch size effect and the patch isolation effect are driven mainly by a single underly- ing process, the sample area effect. The hypothesis predicts that species richness in equal-sized sample sites should increase with the total amount of habitat in the ‘local landscape’ of the sample site, where the local landscape is the area within an appropriate distance of the sample site. It also predicts that species richness in a sample site is independent of the area of the particular patch in which the sample site is located (its ‘local patch’), except insofar as the area of that patch contributes to the amount of habitat in the local landscape of the sample site. The habitat amount hypothesis replaces two predictor variables, patch size and isolation, with a single predictor variable, habitat amount, when species richness is analysed for equal-sized sample sites rather than for unequal-sized habitat patches. -

Integrating Landscape Ecology Into Natural Resource Management

edited by jianguo liu michigan state university william w. taylor michigan state university Integrating Landscape Ecology into Natural Resource Management published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building,Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207,Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House,The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Cambridge University Press 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Lexicon (The Enschedé Font Foundry) 10/14 pt System QuarkXPress™ [se] Acatalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Integrating landscape ecology into natural resource management / edited by Jianguo Lui and William W.Taylor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0 521 78015 2 – ISBN 0 521 78433 6 (pb.) 1. Landscape ecology. 2. Natural resources. I. Liu, Jianguo, 1963– II. Taylor,William W. QH541.15.L35 I56 2002 333.7 – dc21 2001052879 ISBN 0 521 78015 2 hardback ISBN 0 521 78433 6 paperback Contents List of contributors x Foreword xiv eugene p.odum Preface xvi Acknowledgments xviii part i Introduction and concepts 1 1 Coupling landscape ecology with natural resource management: Paradigm shifts and new approaches 3 jianguo liu and william w. -

Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity

30 Sep 2003 15:53 AR AR200-ES34-18.tex AR200-ES34-18.sgm LaTeX2e(2002/01/18) P1: GCE 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132419 Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003. 34:487–515 doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132419 Copyright c 2003 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved First published online as a Review in Advance on August 14, 2003 EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION ON BIODIVERSITY Lenore Fahrig Ottawa-Carleton Institute of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1S 5B6; email: Lenore [email protected] Key Words habitat loss, landscape scale, habitat configuration, patch size, patch isolation, extinction threshold, landscape complementation ■ Abstract The literature on effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity is huge. It is also very diverse, with different authors measuring fragmentation in dif- ferent ways and, as a consequence, drawing different conclusions regarding both the magnitude and direction of its effects. Habitat fragmentation is usually defined as a landscape-scale process involving both habitat loss and the breaking apart of habi- tat. Results of empirical studies of habitat fragmentation are often difficult to inter- pret because (a) many researchers measure fragmentation at the patch scale, not the landscape scale and (b) most researchers measure fragmentation in ways that do not distinguish between habitat loss and habitat fragmentation per se, i.e., the breaking apart of habitat after controlling for habitat loss. Empirical studies to date suggest that habitat loss has large, consistently negative effects on biodiversity. Habitat frag- mentation per se has much weaker effects on biodiversity that are at least as likely to be positive as negative. -

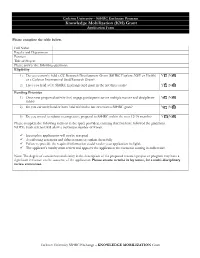

Application Form

Carleton University – SSHRC Exchange Program Knowledge Mobilization (KM) Grant Application Form Please complete the table below. Full Name Faculty and Department Position Title of Project Please answer the following questions: Eligibility 1) Do you currently hold a CU Research Development Grant (SSHRC Explore, NSE or Health) Y |N or a Carleton International Seed Research Grant? 2) Have you held a CU SSHRC Exchange KM grant in the last three years? Y |N Funding Priorities 1) Does your proposed activity (ies) engage participants across multiple sectors and disciplinary Y |N fields? 2) Do you currently hold or have held within the last two years a SSHRC grant? Y |N 3) Do you intend to submit a competitive proposal to SSHRC within the next 12-18 months? Y |N Please complete the following sections in the space provided, ensuring that you have followed the guidelines. NOTE: Each text box will allow a maximum number of words. ✓ Incomplete applications will not be accepted ✓ Avoid using acronyms and abbreviations or explain them fully ✓ Failure to provide the required information could render your application ineligible ✓ The applicant’s faculty must review and approve the application via electronic routing in cuResearch Note: The degree of conciseness and clarity in the description of the proposed research project or program may have a significant influence on the outcome of the application. Please ensure to write in lay terms, for a multi-disciplinary review committee. Carleton University SSHRC Exchange – KNOWLEDGE MOBILIZATION Grant Background (250 words max): provide a brief lay summary of the research results that are being mobilized. -

Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity

30 Sep 2003 15:53 AR AR200-ES34-18.tex AR200-ES34-18.sgm LaTeX2e(2002/01/18) P1: GCE 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132419 Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003. 34:487–515 doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132419 Copyright c 2003 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved First published online as a Review in Advance on August 14, 2003 EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION ON BIODIVERSITY Lenore Fahrig Ottawa-Carleton Institute of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1S 5B6; email: Lenore [email protected] Key Words habitat loss, landscape scale, habitat configuration, patch size, patch isolation, extinction threshold, landscape complementation ■ Abstract The literature on effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity is huge. It is also very diverse, with different authors measuring fragmentation in dif- ferent ways and, as a consequence, drawing different conclusions regarding both the magnitude and direction of its effects. Habitat fragmentation is usually defined as a landscape-scale process involving both habitat loss and the breaking apart of habi- tat. Results of empirical studies of habitat fragmentation are often difficult to inter- pret because (a) many researchers measure fragmentation at the patch scale, not the landscape scale and (b) most researchers measure fragmentation in ways that do not distinguish between habitat loss and habitat fragmentation per se, i.e., the breaking apart of habitat after controlling for habitat loss. Empirical studies to date suggest that habitat loss has large, consistently negative effects on biodiversity. Habitat frag- mentation per se has much weaker effects on biodiversity that are at least as likely to be positive as negative. -

Information Sessions

MODELING THE EFFECTS OF ROAD NETWORK PATTERNS ON POPULATION PERSISTENCE: RELATIVE IMPORTANCE OF TRAFFIC MORTALITY AND 'FENCE EFFECT' Jochen A.G. Jaeger (E-mail: [email protected], phone: 613-520-2600 - ext 8764, fax: 613-520-2569); Lenore Fahrig (E-mail: [email protected], phone: 613-520-2600 - ext 3856, fax: 613-520-2569); Carleton University, Department of Biology, Landscape Ecology Laboratory, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, ON, K1S 5B6, Canada Abstract: Roads affect animals in three adverse ways. They act as barriers to movement ('fence effect'), enhance mortality due to collisions with traffic, and decrease habitat size. We study the relative importance of the first two effects using a spatially explicit individual-based model of population dynamics. We discuss our results with respect to the suitability of fences along roads as a measure to reduce road mortality. The results reveal a much stronger effect of road mortality than of the 'fence effect'; the influence of traffic mortality is always much more significant when the proportions of individuals avoiding the road and those that are killed on the road (in relation to the number of individuals encountering roads) in the two situations compared are the same. The results indicate that putting up fences along roads might be a useful interim mitigation measure until more suitable measures will be applied. However, fences must be used with caution because they could increase extinction risk for species that have large area requirements and small population sizes. In the second part of this paper, we outline a comparison of different configurations of road networks. -

Wildlife Habitat Fragmentation

Wildlife Habitat Fragmentation Natural habitat is quickly disappearing across the North Ameri- can landscape, largely due to habitat fragmentation. Fragmen- tation occurs when connected natural areas are disjointed by habitat removal, converted to urban or agricultural land, or physical barriers such as fences and roadways are con- structed. Habitat fragmentation bisects the landscape and leaves smaller, more isolated land for wildlife, causing local and population level changes to native flora and fauna. Frag- mentation can shift habitat use and provide opportunity for invasions of non-native species.1, 2 EFFECTS OF CAUSES OF FRAGMENTATION ON WILDLIFE FRAGMENTATION Patch-Size Effects Agriculture and Livestock Fragmentation can negatively im- Management pact large-bodied or wide-ranging Large tracts of land are increasingly species that depend on large areas at risk of conversion from natural Edge Effect: When the habitat of the black-capped of favorable habitat to survive by ecosystems to agriculture fields as vireo (Vireo atricapilla) is fragmented, this avian spe- reducing landscape patch-size and global human population increases cies is exposed to the danger of brood parasitism on increasing movement barriers.3 and the demand for food rises.6 The the habitat’s edge by the brown-headed cowbird impacts of fragmentation can be 17 Edge Effects (Molothrus alter). This photo shows a black-capped reduced by the development of Fragmentation increases the vireo feeding a cowbird chick (Credit: Gil Eckrich). buffer zones around fragmented amount of “edge” in a landscape, habitats in order to protect those which can negatively impact wildlife natural habitats from agricultural by causing changes in abiotic disturbances on neighboring land. -

Ecological Responses to Habitat Fragmentation Per Se

ES48CH01-Fahrig ARI 18 September 2017 16:55 Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics Ecological Responses to Habitat Fragmentation Per Se Lenore Fahrig Geomatics and Landscape Ecology Research Laboratory, Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017. 48:1–23 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on landscape pattern, landscape structure, landscape configuration, landscape May 31, 2017 complementation, landscape connectivity, landscape heterogeneity, patch The Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and area, patch isolation, edge effect, SLOSS Systematics is online at ecolsys.annualreviews.org https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316- Abstract 022612 For this article, I reviewed empirical studies finding significant ecological Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. responses to habitat fragmentation per se—in other words, significant re- All rights reserved sponses to fragmentation independent of the effects of habitat amount (here- after referred to as habitat fragmentation). I asked these two questions: Are most significant responses to habitat fragmentation negative or positive? And do particular attributes of species or landscapes lead to a predominance of negative or positive significant responses? I found 118 studies reporting ANNUAL REVIEWS Further 381 significant responses to habitat fragmentation independent of habitat Click here to view this article's amount. Of these responses, 76% were positive. Most significant fragmen- online features: • Download figures as PPT slides tation effects were positive, irrespective of how the authors controlled for • Navigate linked references • Download citations habitat amount, the measure of fragmentation, the taxonomic group, the type • Explore related articles • Search keywords of response variable, or the degree of specialization or conservation status of the species or species group. -

The Effect of Road Density and Proximity on Predation Attempts on the White Footed Mouse (Peromyscus Leucopus)

The effect of road density and proximity on predation attempts on the white footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) By Richard Downing A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario August 2013 ©, Richard J. Downing ABSTRACT Some authors have hypothesized that observed increases in small mammal populations with increasing road density (after controlling for habitat effects) may be due to predation release. Predation, especially predation by birds, could be reduced in areas with high road density, because of negative effects of roads on predator numbers and/or hunting activity. However, there are no studies testing the relationship between road density and predation rate on small mammals. Based on the predation release hypothesis, I predicted that Peromyscus leucopus placed in sites with higher surrounding paved road density and/or closer to a paved road would experience fewer predation attempts than P. leucopus placed in sites with lower surrounding paved road density and/or farther from a paved road. Considering all predators, there was no evidence of any decrease in predation attempts in relation to paved road density, but the credible interval was wide, and the possibility of a biologically relevant increase could not be ruled out. Considering only raptorial birds there was evidence of a decrease in predation attempts with paved road density, and an increase with increasing distance from the road, as predicted. However, the number of raptors was small and this change was not observed for the more numerous specialist mammalian predators. -

Effects of Road Fencing on Population Persistence

Effects of Road Fencing on Population Persistence JOCHEN A. G. JAEGER∗ AND LENORE FAHRIG Ottawa-Carleton Institute of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, ON, K1S 5B6, Canada Abstract: Roads affect animal populations in three adverse ways. They act as barriers to movement, enhance mortality due to collisions with vehicles, and reduce the amount and quality of habitat. Putting fences along roads removes the problem of road mortality but increases the barrier effect. We studied this trade-off through a stochastic, spatially explicit, individual-based model of population dynamics. We investigated the conditions under which fences reduce the impact of roads on population persistence. Our results showed that a fence may or may not reduce the effect of the road on population persistence, depending on the degree of road avoidance by the animal and the probability that an animal that enters the road is killed by a vehicle. Our model predicted a lower value of traffic mortality below which a fence was always harmful and an upper value of traffic mortality above which a fence was always beneficial. Between these two values the suitability of fences depended on the degree of road avoidance. Fences were more likely to be beneficial the lower the degree of road avoidance and the higher the probability of an animal being killed on the road. We recommend the use of fences when traffic is so high that animals almost never succeed in their attempts to cross the road or the population of the species of concern is declining and high traffic mortality is known to contribute to the decline. -

Disturbance OHV Citations to 2008

Disturbance Effects Related to OHV Use and Roads References, last update June 1, 2008 (keywords searched: disturbance, habitat disturbance, human disturbance, proximity, human proximity, avoidance, habitat degradation, trampling, effect; impact, human impact) 1184. Abele, G., J. K. Brown, and M. C. Brewer. 1984. Long-term effects of off-road vehicle traffic on tundra terrain. Journal of Terramechanics 21(3): 283-294. 1244. Adams, J. A., A. S. Endo, L. H. Stolzy, P. G. Rowlands, and H. B. Johnson. 1982. Controlled experiments on soil compaction produced by off-road vehicles in the Mojave Desert, California. Journal of Applied Ecology 19: 167-175. 1285. Adams, L. W., and A. D. Geis. 1983. Effects of roads on small mammals. Journal of Applied Ecology 20: 403-415. 1117. Ahlstrand, G. M., and C. H. Racine. 1993. Response of an Alaska, USA, shrub- tussock community to selected all-terrain vehicle use. Arctic and Alpine research 25(2): 142-149. 1137. Albrecht, J., and T. B. Knopp. 1985. Off Road Vehicles - Environmental Impact - Management Response: A Bibliography. Miscellaneous Publication No. 35. Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. 1286. Alexander, S., and N. Waters. 2000. The effects of highway transportation corridors on wildlife: A case study of Banff National Park. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 8: 307-320. 1026. Allaback, Mark L., and David M. Laabs. 2002/2003. Effectiveness of road tunnels for the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander. Transactions of the Western Section of The Wildlife Society 38/39: 5-8. 113. Allan, B. F., F. Keesing, and R. S. Ostfeld. 2003.