Delirium and Dementia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict, Arousal, and Logical Gut Feelings

CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Wim De Neys1, 2, 3 1 ‐ CNRS, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 2 ‐ Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 3 ‐ Université de Caen Basse‐Normandie, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France Mailing address: Wim De Neys LaPsyDÉ (Unité CNRS 3521, Université Paris Descartes) Sorbonne - Labo A. Binet 46, rue Saint Jacques 75005 Paris France [email protected] ABSTRACT Although human reasoning is often biased by intuitive heuristics, recent studies on conflict detection during thinking suggest that adult reasoners detect the biased nature of their judgments. Despite their illogical response, adults seem to demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to possible conflict between their heuristic judgment and logical or probabilistic norms. In this chapter I review the core findings and try to clarify why it makes sense to conceive this logical sensitivity as an intuitive gut feeling. CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Imagine you’re on a game show. The host shows you two metal boxes that are both filled with $100 and $1 dollar bills. You get to draw one note out of one of the boxes. Whatever note you draw is yours to keep. The host tells you that box A contains a total of 10 bills, one of which is a $100 note. He also informs you that Box B contains 1000 bills and 99 of these are $100 notes. So box A has got one $100 bill in it while there are 99 of them hiding in box B. Which one of the boxes should you draw from to maximize your chances of winning $100? When presented with this problem a lot of people seem to have a strong intuitive preference for Box B. -

Panic Disorder Issue Brief

Panic Disorder OCTOBER | 2018 Introduction Briefings such as this one are prepared in response to petitions to add new conditions to the list of qualifying conditions for the Minnesota medical cannabis program. The intention of these briefings is to present to the Commissioner of Health, to members of the Medical Cannabis Review Panel, and to interested members of the public scientific studies of cannabis products as therapy for the petitioned condition. Brief information on the condition and its current treatment is provided to help give context to the studies. The primary focus is on clinical trials and observational studies, but for many conditions there are few of these. A selection of articles on pre-clinical studies (typically laboratory and animal model studies) will be included, especially if there are few clinical trials or observational studies. Though interpretation of surveys is usually difficult because it is unclear whether responders represent the population of interest and because of unknown validity of responses, when published in peer-reviewed journals surveys will be included for completeness. When found, published recommendations or opinions of national organizations medical organizations will be included. Searches for published clinical trials and observational studies are performed using the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database using key words appropriate for the petitioned condition. Articles that appeared to be results of clinical trials, observational studies, or review articles of such studies, were accessed for examination. References in the articles were studied to identify additional articles that were not found on the initial search. This continued in an iterative fashion until no additional relevant articles were found. -

Depression and Delirium of the Older Adult Interprofessional Geriatrics

3/1/2018 Interprofessional Geriatrics Training Program Depression and Delirium of the Older Adult HRSA GERIATRIC WORKFORCE ENHANCEMENT FUNDED PROGRAM Grant #U1QHP2870 EngageIL.com Acknowledgements Authors: Curie Lee, DNP, AGPCNP-BC, RN L. Amanda Perry, MD Editors: Valerie Gruss, PhD, APN, CNP-BC Memoona Hasnain, MD, MHPE, PhD Learning Objectives Upon completion of this module, learners will be able to: 1. Summarize the difference between delirium and depression in older adults 2. Discuss the use of standardized tools for measuring cognitive, behavioral, and/or mood changes to confirm diagnoses 3. Discuss the structured assessment method to make a differential diagnosis based on the clinical features of delirium and depression 4. Apply management principles according to pharmacologic/ nonpharmacologic strategies 5. Identify materials to educate patients and family/caregivers 1 3/1/2018 Delirium vs. Depression • Delirium and depression can coexist but are not the same diagnosis • Both have Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for diagnosis: • Delirium is the acute onset of behavioral changes and/or confusion and often has an organic cause; resolution is often as abrupt as onset • Depression can be acute or insidious in onset and can last for years; though pathology can exacerbate the depression, it is not the cause of the depression Note: Depression in the geriatric population can be confused with delirium or dementia Delirium Delirium: Definition DSM-5: Five Key Features of Delirium 1) Disturbance in attention and awareness 2) Disturbance develops over a short period of time, represents a change from baseline, and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day 3) An additional disturbance in cognition Continued on next slide.. -

Relationship Between the Postoperative Delirium And

Theory iMedPub Journals Journal of Neurology and Neuroscience 2020 www.imedpub.com Vol.11 No.5:332 ISSN 2171-6625 DOI: 10.36648/2171-6625.11.1.332 Relationship Between the Postoperative Delirium and Dementia in Elderly Surgical Patients: Alzheimer’s Disease or Vascular Dementia Relevant Study Jong Yoon Lee1*, Hae Chan Ha2, Noh June Mo2, Hong Kyung Ho2 1Department of Neurology, Seoul Chuk Hospital, Seoul, Korea. 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul Chuk Hospital, Seoul, Korea. *Corresponding author: Jong Yoon Lee, M.D. Department of Neurology, Seoul Chuk Hospital, 8, Dongsomun-ro 47-gil Seongbuk-gu Seoul, Republic of Korea, Tel: + 82-1599-0033; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: June 13, 2020; Accepted date: August 21, 2020; Published date: August 28, 2020 Citation: Lee JY, Ha HC, Mo NJ, Ho HK (2020) Relationship Between the Postoperative Delirium and Dementia in Elderly Surgical Patients: Alzheimer’s Disease or Vascular Dementia Relevant Study. J Neurol Neurosci Vol.11 No.5: 332. gender and CRP value {HTN, 42.90% vs. 43.60%: DM, 45.50% vs. 33.30%: female, 27.2% of 63.0 vs. male 13.8% Abstract of 32.0}. Background: Delirium is common in elderly surgical Conclusion: Dementia play a key role in the predisposing patients and the etiologies of delirium are multifactorial. factor of POD in elderly patients, but found no clinical Dementia is an important risk factor for delirium. This difference between two subgroups. It is estimated that study was conducted to investigate the clinical relevance AD and VaD would share the pathophysiology, two of surgery to the dementia in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or subtype dementia consequently makes a similar Vascular dementia (VaD). -

Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children and Their Anesthetic Implications

children Review Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children and Their Anesthetic Implications Srijaya K. Reddy 1,* and Nina Deutsch 2 1 Department of Anesthesiology, Division of Pediatric Anesthesiology—Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2200 Children’s Way Suite 3116, Nashville, TN 37232, USA 2 Division of Anesthesiology, Pain and Perioperative Medicine—Children’s National Hospital, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, 111 Michigan Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20010, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +01-(615)-936-0023 Received: 16 October 2020; Accepted: 21 November 2020; Published: 25 November 2020 Abstract: While most children have anxiety and fears in the hospital environment, especially prior to having surgery, there are several common behavioral and emotional disorders in children that can pose a challenge in the perioperative setting. These include anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. The aim of this review article is to provide a brief overview of each disorder, explore the impact on anesthesia and perioperative care, and highlight some management techniques that can be used to facilitate a smooth perioperative course. Keywords: child behavioral disorders; attention deficit and disruptive behavior disorders; perioperative care; anesthesia; autism spectrum disorder; premedication; emergence delirium 1. Introduction Anxiety and fear are common emotions for children to experience when faced with the need to undergo a surgical or diagnostic procedure, with Kain and colleagues determining that up to 60% of all children undergoing anesthesia and surgery report significant anxiety [1]. -

Defining Delirium in Idiopathic Parkinson's Disease

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Newcastle University E-Prints Defining delirium in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review Rachael A Lawson1,2, Claire McDonald1,3, David J Burn4 1. Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University, UK 2. Newcastle University Institute for Ageing, Newcastle University, UK 3. Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK 4. Faculty of Medical Science, Newcastle University, UK Corresponding author: Rachael A Lawson Clinical Ageing Research Unit Institute of Neuroscience Newcastle University Institute for Ageing Newcastle University Campus for Ageing and Vitality Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 5PL 0191 208 1277 [email protected] Word count: 3520 Figures: 1 Tables: 3 Running title: Defining delirium in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease Key words: Parkinson’s disease, delirium, prevalence, systematic review. 1 Abstract Background: Parkinson’s disease patients may be at increased risk of delirium and developing adverse outcomes, such as cognitive decline and increased mortality. Delirium is an acute state of confusion that has overlapping symptoms with Parkinson’s dementia, making it difficult to identify. This study aimed to determine the diagnostic criteria, prevalence, management strategies and outcomes of delirium in Parkinson’s through a systematic review of the literature. Methods: Seven databases were used to identify all articles published before February 2017 comprising two key terms: “Parkinson’s Disease” and “delirium”. Data were extracted from studies meeting predefined inclusion criteria. Results: Twenty articles were identified. Delirium prevalence in Parkinson’s ranged from 0.3-60% depending on setting; a diagnosis of Parkinson’s was associated with an increased risk of developing delirium. -

Mild Cognitive Impairment (Mci) and Dementia February 2017

CareCare Process Process Model Model FEBRUARY MONTH 2015 2017 DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Dementia minor update - 12 / 2020 The Intermountain Cognitive Care Development Team developed this care process model (CPM) to improve the diagnosis and treatment of patients with cognitive impairment across the staging continuum from mild impairment to advanced dementia. It is primarily intended as a tool to assist primary care teams in making the diagnosis of dementia and in providing optimal treatment and support to patients and their loved ones. This CPM is based on existing guidelines, where available, and expert opinion. WHAT’S INSIDE? Why Focus ON DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT ALGORITHMS OF DEMENTIA? Algorithm 1: Diagnosing Dementia and MCI . 6 • Prevalence, trend, and morbidity. In 2016, one in nine people age 65 and Algorithm 2: Dementia Treatment . .. 11 older (11%) has Alzheimer’s, the most common dementia. By 2050, that Algorithm 3: Driving Assessment . 13 number may nearly triple, and Utah is expected to experience one of the Algorithm 4: Managing Behavioral and greatest increases of any state in the nation.HER,WEU One in three seniors dies with Psychological Symptoms . 14 a diagnosis of some form of dementia.ALZ MCI AND DEMENTIA SCREENING • Costs and burdens of care. In 2016, total payments for healthcare, long-term AND DIAGNOSIS ...............2 care, and hospice were estimated to be $236 billion for people with Alzheimer’s MCI TREATMENT AND CARE ....... HUR and other dementias. Just under half of those costs were borne by Medicare. MANAGEMENT .................8 The emotional stress of dementia caregiving is rated as high or very high by nearly DEMENTIA TREATMENT AND PIN, ALZ 60% of caregivers, about 40% of whom suffer from depression. -

![Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9395/arxiv-2011-03588v1-cs-cl-6-nov-2020-1219395.webp)

Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020

Hostility Detection Dataset in Hindi Mohit Bhardwajy, Md Shad Akhtary, Asif Ekbalz, Amitava Das?, Tanmoy Chakrabortyy yIIIT Delhi, India. zIIT Patna, India. ?Wipro Research, India. fmohit19014,tanmoy,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Despite Hindi being the third most spoken language in the world, and a significant presence of Hindi content on social In this paper, we present a novel hostility detection dataset in Hindi language. We collect and manually annotate ∼ 8200 media platforms, to our surprise, we were not able to find online posts. The annotated dataset covers four hostility di- any significant dataset on fake news or hate speech detec- mensions: fake news, hate speech, offensive, and defamation tion in Hindi. A survey of the literature suggest a few works posts, along with a non-hostile label. The hostile posts are related to hostile post detection in Hindi, such as (Kar et al. also considered for multi-label tags due to a significant over- 2020; Jha et al. 2020; Safi Samghabadi et al. 2020); however, lap among the hostile classes. We release this dataset as part there are two basic issues with these works - either the num- of the CONSTRAINT-2021 shared task on hostile post detec- ber of samples in the dataset are not adequate or they cater tion. to a specific dimension of the hostility only. In this paper, we present our manually annotated dataset for hostile posts 1 Introduction detection in Hindi. We collect more than ∼ 8200 online so- The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives forever, cial media posts and annotate them as hostile and non-hostile both online and offline. -

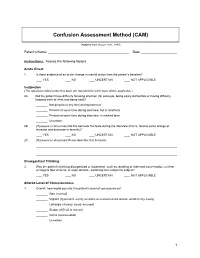

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6. -

Delirium & Delirious Mania

Delirium & Delirious Mania; Differential Diagnosis. Delirium & Delirious Mania; Differential Diagnosis. Author: Eline Janszen. (s894226) Thesis-Supervisor: Ruth Mark Bachelorthesis Clinical Health Psychology Department of Neuropsychology, University of Tilburg September, 2011. 1 Delirium & Delirious Mania; Differential Diagnosis. ABSTRACT In the last few years, delirium in hospitals and in the elderly population has become an important subject of various studies, resulting in the recognition of several subtypes; hyperactive delirium, hypoactive delirium and mixed delirium. The first one of these subtypes, hyperactive delirium, shows a lot of overlap with another syndrome: Delirious mania. The current literature review examines both syndromes, discussing the overlap and the differences of their symptoms, while also looking at the neurological structures involved. Search engines including Sciencedirect, PSYCHinfo and medline were used to find the relevant literature. The data found in this examination reveals that, in spite of the several overlapping symptoms, delirious mania and hyperactive delirium are different syndromes; hyperactive delirium is associated with symptoms like hyperactivity, circardian rhythm disturbances and neurological abnormalities that include lesions of the hippocampus and dysfunction of the orbitofrontal cortex while delirious mania shows distinctive symptoms like pouring water and denudativeness (disrobing) with neurological abnormalities that also include orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction, but suffer mostly from an overall frontal circuitry dysfunction. This distinction is important for clinical outcome, seeing as that hyperactive delirium is treated with haloperidol and the preferred treatment for delirious mania is ECT. Keywords: delirium, hyperactive delirium, delirious mania. 2 Delirium & Delirious Mania; Differential Diagnosis. INTRODUCTION In recent years there has been a lot of research focused on diagnosing delirium. Since patients with delirium display fluctuating symptoms, the distinction from other conditions can be difficult. -

Chapter 36: Recognizing Delirium, Dementia, and Depression

Chapter 36: Recognizing Delirium, Dementia, and Depression Manjula Kurella Tamura Division of Nephrology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California Neuropsychiatric disorders such as delirium, demen- high risk. Several ESKD-specific syndromes of delir- tia, and depression are common yet poorly recognized ium deserve special mention: causes of morbidity and mortality among elderly per- sons with chronic kidney disease (CKD) including Uremic Encephalopathy. end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Patients with neu- Uremic encephalopathy is a syndrome of delirium ropsychiatric disorders are at higher risk for death, seen in untreated ESKD. It is characterized by lethargy hospitalization, and dialysis withdrawal. These disor- and confusion in early stages and may progress to sei- ders are also likely to reduce quality of life and hinder zures and/or coma. It may be accompanied by other adherence with the complex dietary and medication neurologic signs, such as tremor, myoclonus, or as- regimens prescribed to patients with CKD. This chap- terixis. Although rarely used for diagnostic purposes, ter will review the evaluation and management of de- the EEG shows a characteristic pattern in patients with lirium, dementia, and depression among persons with uremic encephalopathy.2 The syndrome is rapidly re- CKD and ESKD. versed with dialysis or kidney transplantation. Dialysis Dysequilibrium. DELIRIUM This syndrome of delirium is seen during or after the first several dialysis treatments. It is most likely Delirium is an acute confusional state characterized to occur in elderly patients with severe azotemia by a recent onset of fluctuating awareness, impair- undergoing high efficiency hemodialysis; however, ment of memory and attention, and disorganized it has also been reported in patients undergoing thinking that can be attributable to a medical con- peritoneal dialysis and long-term hemodialysis.3 dition, intoxication, or medication side effects. -

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running Head

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running head: RELATIONAL EMPATHY The Interpersonal Functions of Empathy: A Relational Perspective Alexandra Main, Eric A. Walle, Carmen Kho, & Jodi Halpern Alexandra Main Carmen Kho University of California, Merced University of California, Merced 5200 N Lake Road 5200 N Lake Road Merced, CA 95343 Merced, CA 95343 Phone: 209-228-2429 Phone: 714-253-6163 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Eric A. Walle Jodi Halpern University of California, Merced University of California, Berkeley 5200 N Lake Road 570 University Hall Merced, CA 95343 Berkeley, CA 94720 Phone: 209-228-4634 Phone: 510-642-4366 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alexandra Main, Psychological Sciences, 5200 North Lake Road, University of California, Merced, CA 95343. Phone: 209-228-2429, Email: [email protected] RELATIONAL EMPATHY 2 Abstract Empathy is an extensively studied construct, but operationalization of effective empathy is routinely debated in popular culture, theory, and empirical research. This paper offers a process-focused approach emphasizing the relational functions of empathy in interpersonal contexts. We argue that this perspective offers advantages over more traditional conceptualizations that focus on primarily intrapsychic features (i.e., within the individual). Our aim is to enrich current conceptualizations and empirical approaches to the study of empathy by drawing on psychological, philosophical, medical, linguistic, and anthropological perspectives. In doing so, we highlight the various functions of empathy in social interaction, underscore some underemphasized components in empirical studies of empathy, and make recommendations for future research on this important area in the study of emotion.