Negative Swap Spreads and Limited Arbitrage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Profit Model for Spread Trading with an Application to Energy Futures

A profit model for spread trading with an application to energy futures by Takashi Kanamura, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi No. 27 | MAY 2011 WORKING PAPER SERIES IN ECONOMICS KIT – University of the State of Baden-Wuerttemberg and National Laboratory of the Helmholtz Association econpapers.wiwi.kit.edu Impressum Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften Institut für Wirtschaftspolitik und Wirtschaftsforschung (IWW) Institut für Wirtschaftstheorie und Statistik (ETS) Schlossbezirk 12 76131 Karlsruhe KIT – Universität des Landes Baden-Württemberg und nationales Forschungszentrum in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft Working Paper Series in Economics No. 27, May 2011 ISSN 2190-9806 econpapers.wiwi.kit.edu A Profit Model for Spread Trading with an Application to Energy Futures Takashi Kanamura J-POWER Svetlozar T. Rachev¤ Chair of Econometrics, Statistics and Mathematical Finance, School of Economics and Business Engineering University of Karlsruhe and KIT, Department of Statistics and Applied Probability University of California, Santa Barbara and Chief-Scientist, FinAnalytica INC Frank J. Fabozzi Yale School of Management October 19, 2009 ABSTRACT This paper proposes a profit model for spread trading by focusing on the stochastic move- ment of the price spread and its first hitting time probability density. The model is general in that it can be used for any financial instrument. The advantage of the model is that the profit from the trades can be easily calculated if the first hitting time probability density of the stochastic process is given. We then modify the profit model for a particular market, the energy futures market. It is shown that energy futures spreads are modeled by using a mean- reverting process. -

Curve Building and Swap Pricing in the Presence of Collateral and Basis Spreads

Curve Building and Swap Pricing in the Presence of Collateral and Basis Spreads SIMON GUNNARSSON Master of Science Thesis Stockholm, Sweden 2013 Curve Building and Swap Pricing in the Presence of Collateral and Basis Spreads SIMON GUNNARSSON Master’s Thesis in Mathematical Statistics (30 ECTS credits) Master Programme in Mathematics (120 credits) Supervisor at KTH was Boualem Djehiche Examiner was Boualem Djehiche TRITA-MAT-E 2013:19 ISRN-KTH/MAT/E--13/19--SE Royal Institute of Technology School of Engineering Sciences KTH SCI SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden URL: www.kth.se/sci Abstract The eruption of the financial crisis in 2008 caused immense widening of both domestic and cross currency basis spreads. Also, as a majority of all fixed income contracts are now collateralized the funding cost of a financial institution may deviate substantially from the domestic Libor. In this thesis, a framework for pricing of collateralized interest rate derivatives that accounts for the existence of non-negligible basis spreads is implemented. It is found that losses corresponding to several percent of the outstanding notional may arise as a consequence of not adapting to the new market conditions. Keywords: Curve building, swap, basis spread, cross currency, collateral Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisor Boualem Djehiche as well as Per Hjortsberg and Jacob Niburg for introducing me to the subject and for providing helpful feedback along the way. I also wish to express gratitude towards my family who has supported me throughout my education. Finally, I am grateful that Marcus Josefsson managed to devote a few hours to proofread this thesis. -

Specialty Strategies

RCM Alternatives: AlternaRCt M ve s Whitepaper Specialty Strategies 318 W Adams St 10th FL | Chicago, IL 60606 | 855-726-0060 www.rcmalternatives.com | [email protected] RCM Alternatives: Specialty Strategies RCM It’s fairly common for “trend following” and “managed futures” to be used interchangeably. But there are many more strategies out there beyond the standard approach – a variety of approaches that we call Specialty Strategies. Specialty strategies include short-term, options, and spread traders. Short-Term Systematic Traders The cousin to the multi-market systematic trend is the trading equivalent of an arms race that most follower, the short-term systematic program will also money managers want to stay as far away from as look to latch onto a “trend” in an effort to make a possible. profit. The difference here has to do with timeframe, and how that impacts their trend identification, What types of shorter-term traders can we length of trade, and performance during volatile expect to invest with? First, there are day trading times. Unlike longer-term trend followers, short-term strategies. A day trading system is defined by a systematic traders may believe an hours-long move is single characteristic: that it will NOT hold a position enough to represent a trend, allowing them to take overnight, with all positions covered by the end of advantage of market moves that are much shorter in the trading day. This appeals to many investors who duration. One man’s noise is another’s treasure in the don’t like the prospect of something happening in minds of short term traders. -

A Study on Advantages of Separate Trade Book for Bull Call Spreads and Bear Put Spreads

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668 PP 11-20 www.iosrjournals.org A Study on Advantages of Separate Trade book for Bull Call Spreads and Bear Put Spreads. Chirag Babulal Shah PhD (Pursuing), M.M.S., B.B.A., D.B.M., P.G.D.F.T., D.M.T.T. Assistant Professor at Indian Education Society’s Management College and Research Centre. Abstract: Derivatives are revolutionary instruments and have changed the way one looks at the financial world. Derivatives were introduced as a hedging tool. However, as the understanding of the intricacies of these instruments has evolved, it has become more of a speculative tool. The biggest advantage of Derivative instruments is the leverage it provides. The other benefit, which is not available in the spot market, is the ability to short the underlying, for more than a day. Thus it is now easy to take advantage of the downtrend. However, the small retail participants have not had a good overall experience of trading in derivatives and the public at large is still bereft of the advantages of derivatives. This has led to a phobia for derivatives among the small retail market participants, and they prefer to stick to the old methods of investing. The three main reasons identified are lack of knowledge, the margining methods and the quantity of the lot size. The brokers have also misled their clients and that has led to catastrophic results. The retail participation in the derivatives markets has dropped down dramatically. But, are these derivative instruments and especially options, so bad? The answer is NO. -

Affidavit of Stewart Mayhew

Affidavit of Stewart Mayhew I. Qualifications 1. I am a Principal at Cornerstone Research, an economic and financial consulting firm, where I have been working since 2010. At Cornerstone Research, I have conducted statistical and economic analysis for a variety of matters, including cases related to securities litigation, financial institutions, regulatory enforcement investigations, market manipulation, insider trading, and economic studies of securities market regulations. 2. Prior to working at Cornerstone Research, I worked at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC” or “Commission”) as Deputy Chief Economist (2008-2010), Assistant Chief Economist (2004-2008), and Visiting Academic Scholar (2002-2004). From 2004 to 2008, I headed a group that was responsible for providing economic analysis and support for the Division of Trading and Markets (formerly known as the Division of Market Regulation), the Division of Investment Management, and the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations. Among my responsibilities were to analyze SEC rule proposals relating to market structure for the trading of stocks, bonds, options, and other products, and to perform analysis in connection with compliance examinations to assess whether exchanges, dealers, and brokers were complying with existing rules. I also assisted the Division of Enforcement on numerous investigations and enforcement actions, including matters involving market manipulation. 3. I have taught doctoral level, masters level, and undergraduate level classes in finance as Assistant Professor in the Finance Group at the Krannert School of Management, Purdue University (1996-1999), as Assistant Professor in the Department of Banking and Finance at the Terry College of Business, University of Georgia (2000-2004), and as a Lecturer at the Robert H. -

Evidence from a Financial Crisis Emanuela Giacomini *, Xiaohong

Effects of Bank Lending Shocks on Real Activity: Evidence from a Financial Crisis a a Emanuela Giacomini *, Xiaohong (Sara) Wang a Graduate School of Business, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-7168, USA January 15, 2012 Abstract U.S. banks experienced dramatic declines in capital and liquidity during the financial crisis of 2007-2009. We study the effect of shocks on banks’ capital and liquidity positions on their borrowers’ investment decisions. The recent financial crisis serves as a natural experiment in the sense that the crisis was not expected by banks ex-ante, and had a detrimental but heterogeneous impact on banks’ capitals and liquidity positions ex-post. Consistent with our hypothesis, we find that borrowers of more affected banks reduced more investment during the crisis. We find that borrowing firms whose banks have a higher level of non-performing loans and lower level of tier one capital, hold less liquid asset, and experience greater stock price drop tend to invest less in the capital expenditure when comparing investment before and during the crisis. Shocks on banks, however, have limited effect on firm R&D expenditures and net working capital. Our results suggest that shocks on banks’ capital and liquidity positions negatively affect borrowers’ investment levels, in particular their capital expenditures. EFM Classification Codes: 510, 520. * Corresponding author. Tel.: 352 392 8913; fax: 352 392 0301. E-mail address: [email protected] (Emanuela Giacomini), [email protected] (Xiaohong (Sara) Wang). 1 1. Introduction During the 2007-2009 financial crisis, U.S. banks experienced dramatic declines in capital from bad loan write-downs and collateralized debt obligation value plunges. -

The Global Credit Spread Puzzle∗

The Global Credit Spread Puzzle∗ Jing-Zhi Huangy Yoshio Nozawaz Zhan Shix Penn State HKUST Tsinghua University December 19, 2019 Abstract Using security-level credit spread data in eight developed economies, we document a large cross- country difference in credit spreads conditional on credit ratings and other default risk measures. The standard benchmark structural models not only have difficulty matching credit spreads but also fail to explain the cross-country variation in spreads as well as the dynamic behavior of credit spreads. Since this cross-country variation is positively related to illiquidity measures, we implement an extended structural model that incorporates endogenous liquidity in the secondary market, and find that this model largely explains credit spreads in cross sections and over time. Therefore, default risk itself unlikely explains corporate credit spreads. JEL Classification: G12, G13 Keywords: Corporate credit spreads, Credit spread puzzle, Structural credit risk models, the Merton model, the Black and Cox model, CDS, Fixed income asset pricing ∗We would like to thank Antje Berndt (discussant), Mehmet Canayaz, Hui Chen, Wenxin Du, Nicolae G^arleanu, Bob Goldstein, Zhiguo He, Grace Hu, Ralph Koijen, Anh Le, Juhani Linnainmaa, Christian Lundblad, Jayoung Nam (discussant), Carolin Pflueger, Alberto Plazzi (discussant), Scott Richardson, Michael Schwert, Matt Spiegel, Fan Yang (discussant), and Haoxiang Zhu; and seminar participants at CICF, the Dolomite Winter Finance Conference, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, HKUST, Lugano, SWUFE, Tsinghua University, and the University of Con- necticut Finance Conference for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Terrence O'Brien, Shasta Shakya, and Hongyu Yao for their able research assistance. The initial draft of the paper was prepared when Yoshio Nozawa was at the Federal Reserve Board. -

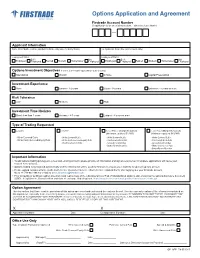

Options Application and Agreement Member FINRA/SIPC Firstrade Account Number (If Application Is for an Existing Account – Otherwise Leave Blank)

Options Application and Agreement Member FINRA/SIPC Firstrade Account Number (if application is for an existing account – otherwise leave blank) Applicant Information Name (First, Middle, Last for individual / indicate entity name for Entity/Trusts) Co-Applicant’s Name (For Joint Accounts Only) Employment Status Employment Status Self- Not Self- Not Employed Employed Retired Student Homemaker Employed Employed Employed Retired Student Homemaker Employed Options Investment Objectives (Level 2, 3 & 4 require “Speculation” to be checked) Speculation Growth Income Capital Preservation Investment Experience None Limited - 1-2 years Good - 3-5 years Extensive - 5 years or more Risk Tolerance Low Medium High Investment Time Horizon Short- less than 3 years Average - 4-7 years Longest - 8 years or more Type of Trading Requested Level 1 Level 2 Level Three (Margin Required) Level Four (Margin Required) (Minimum equity of $2,000) (Minimum equity of $10,000) • Write Covered Calls • Write Covered Calls • Write Covered Calls • Write Covered Calls • Write Cash-Secured Equity Puts • Write Cash-Secured Equity Puts • Purchase Calls & Puts • Purchase Calls & Puts • Purchase Calls & Puts • Spreads & Straddles • Spreads & Straddles • Buttery and Condor • Write Uncovered Puts • Buttery and Condor Important Information To add options trading privileges to a new and existing account, please provide all information and signature(s) below. Incomplete applications will cause your request to be delayed. Options trading is not granted automatically and the information will be used by Firstrade to assess your eligibility to open an options account. Please upload completed form via the Form Center (Customer Service ->Form Center ->Upload Form) after logging into your Firstrade account, fax to +1-718-961-3919 or e-mail to [email protected] Prior to buying or selling an option, investors must read a copy of the Characteristics & Risk of Standardized Options, also known as the options disclosure document (ODD). -

My Top 5 Rules for Successful Debit Spread Trading Trade with Lower Cost and Create More Consistency in Your Options Portfolio

My Top 5 Rules for Successful Debit Spread Trading Trade with Lower Cost and Create More Consistency in Your Options Portfolio Price Headley, CFA, CMT TABLE OF CONTENTS: How Debit Spreads Give You Growth AND Income Potential Rule #1. Buy In-The-Money and Sell At or Out-Of-The-Money Rule #2. Sell More Time Premium Than You Buy Rule #3. Profit Taking in Pieces Increases Win Percentage Rule #4. Don’t Be Greedy – Favor Early Profit Taking Rule #5. Trade in Pairs How Debit Spreads Give You Growth AND Income Potential If you’ve ever bought an option before, you know that one of the challenges of trading a time-limited asset is paying a “time premium” and overcoming the loss of time. And yet as a trader, I still see plenty of opportunities to take advantage of trends on various time frames, from quick moves over a few days to “swing trading” moves over several weeks. So how can you actually place time on your side in the options game? It’s not by just selling options, as that can be profitable, but many traders have seen how a small number of trades can cause you lots of trouble in option selling if a stock or market moves sharply against you. The answer that meets nicely in the middle – profiting from the growth potential of catching a piece of an existing trend, while lowering your total cost per contract and paying no net time in your options – is Debit Spreads. You may have heard them called Vertical Spreads, or Bull Call Spreads or Bear Put Spreads. -

Market Liquidity Shortage and Banks' Capital Structure and Balance Sheet Adjustments: Evidence from U.S

Market liquidity shortage and banks' capital structure and balance sheet adjustments: evidence from U.S. commercial Banks Thierno Amadou Barry*, Alassane Diabaté1*, Amine Tarazi*,** * Université de Limoges, LAPE, 5 rue Félix Eboué, 87031 Limoges Cedex, France ** Institut Universitaire de France (IUF), 1 rue Descartes, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France This draft: April 26, 2019 Abstract: Using quarterly data of U.S. commercial banks, we investigate the impact of market liquidity shortages on banks’ capitalization and balance sheet adjustments. Our findings reveal that an acute liquidity shortage leads small U.S. commercial banks, but not large ones, to positively adjust their total capital ratio. Small banks adjust their total capital ratio by downsizing, by restricting dividend payments, by decreasing the share of assets with higher risk weights and specifically by extending less loans. Furthermore, the positive impact on total capital ratios is stronger for small banks which are more reliant on market liquidity and small banks operating below their target capital ratio. JEL Classification: G21, G28 Keywords: bank capital ratio, market liquidity shortage, capital structure adjustment 1 Corresponding author. Tel: +33 555149251 *Email Address: [email protected] (T. A. Barry), [email protected] (A. Diabaté), [email protected] (A. Tarazi) 1 Market liquidity shortage and banks' capital structure and balance sheet adjustments: evidence from U.S. commercial Banks Abstract: Using quarterly data of U.S. commercial banks, we investigate the impact of market liquidity shortages on banks’ capitalization and balance sheet adjustments. Our findings reveal that an acute liquidity shortage leads small U.S. commercial banks, but not large ones, to positively adjust their total capital ratio. -

Bond Market Review | May 4, 2020

Bond Market Review | May 4, 2020 Summary Treasury Yields Its wa another solid week for the bond market as the spread sectors and Treasury yields • Treasury Term ∆ MTD ∆ YTD rallied. Accommodative commentary from the Fed and the European Central Bank (ECB) Yield and continued flattening of the virus curve provided the positive catalyst. 1 Year • Munis lagged Treasuries for a second consecutive week although crossover taxable buyers 0.16 0.02 -1.41 entered the tax-free market Thursday to take advantage of the corporate-like yields. 2 Year 0.19 -0.01 -1.38 • Corporate spreads have stabilized at the current elevated levels after moving significantly 5 Year 0.35 -0.01 -1.34 tighter for the month of April. However, most of the tightening occurred in the first two weeks of the month and we’ve been moving sideways since. 10 Year 0.61 -0.03 -1.31 • The market continues to differentiate between credits although we are beginning to see 30 Year 1.25 -0.04 -1.14 investor demand for lower quality bonds Tax-Exempt • After two weeks of relentless price cuts that saw 10-year AAA municipal yields backup 35+ basis points (bps), buyers returned to the secondary market in force on Friday to reach for bonds up and down the yield curve. Although activity slowed by midday with many offerings priced rich or removed altogether ahead of the weekend, gains remained strong to close out the week. • While the McConnell bankruptcy talk has faded, there is potential weakness to deal with in the near-term. -

Intraday Pricing and Liquidity Effects of U.S. Treasury Auctions*

Intraday Pricing and Liquidity Effects of U.S. Treasury Auctions Michael J. Fleming, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Weiling Liu, Harvard University First draft: May 15, 2014 This draft: September 30, 2017 Abstract We examine the intraday effects of U.S. Treasury auctions on the pricing and liquidity of the most recently issued notes. We find that prices decrease in the hours preceding auction and recover in the hours following. The magnitude of the price changes is positively correlated with bid-ask spreads, price impact, volatility, and other measures of financial stress. We further find that liquidity tends to be better right before an auction, albeit worse at auction time and thereafter. Our results provide high frequency evidence of supply shocks causing price pressure effects and show dealers’ limited risk-bearing capacity helps explain such effects. JEL Codes: G12, G14, E43, H63 Keywords: Liquidity; dealer intermediation; price pressure; supply effects; returns Fleming: [email protected], (212) 720-6372); Liu: [email protected]. The authors are grateful to Tobias Adrian, Charles Jones, and seminar participants at the Bank for International Settlements (Asian Office), Bank of Thailand, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning, First International Conference on Sovereign Bond Markets, and FTG Summer School for helpful comments. Ron Yang provided excellent research assistance. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. 1. Introduction The extant literature shows that security supply matters to prices, even in a market as liquid as the U.S.