This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

Bridgwater and Taunton Canal- Maunsel Lock to Creech St Michael

Bridgwater and Taunton Canal- Maunsel Lock to Creech St Michael (and return) Easy to Moderate Trail Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Distance: 8 miles Approximate Time: 2-3 Hours The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Type of Trail: Out and Back Waterways Travelled: Bridgewater and Taunton Canal Type of Water: Rural Canal Portages and Locks: 2 Nearest Town: Bridgewater/ Taunton Start and Finish: Maunsel Lock TA7 0DH O.S. Sheets: OS Map 182 Weston-Super-Mare OS Map Cutting in Bridgewater 193 Taunton and Lyme Regis Route Summary Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle Canoe along one of England’s best kept secrets. The on this waterway. See full details in useful information Bridgwater and Taunton Canal opened in 1827 and links below. the River Tone to the River Parrett. It is a well-kept secret Local Facilities: At the start and part way down the but a well-managed one! Local people, have set up a canal volunteer wardens scheme to look after their canal and their success can be shown in its beauty and peacefulness. This canal might be cut off from the rest of the system, but it has well-maintained towpaths and fascinating lock structures which make for idyllic walking and peaceful boating. -

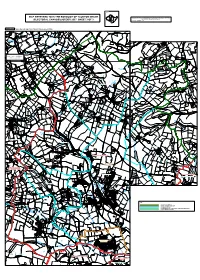

MAP REFERRED to in the BOROUGH of TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU

Sheet 3 3 MAP REFERRED TO IN THE BOROUGH OF TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU. 2 1 Tel: 023 8030 5092 Fax: 023 8079 2035 (ELECTORAL CHANGES) ORDER 2007 SHEET 3 OF 3 © Crown Copyright 2007 SHEET 3, MAP 3 Taunton Deane Borough. Parish Wards in Bishop's Lydeard Parish E N A L E AN D L L OO O P O D W UN RO Roebuck Farm Wes t So mer set Rai lway A 3 5 8 Ashfield Farm Aisholt Wood Quarry L (dis) IL H E E R T H C E E B Hawkridge Common All Saints' Church E F Aisholt AN L L A TE X Triscombe A P Triscombe Quarry Higher Aisholt G O Quarries K O Farm C (Stone) (disused) BU L OE H I R L L Quarry (dis) Flaxpool Roebuck Gate Farm Quarry (dis) Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Quarry (dis) Grid interval 1km Heathfield Farm Luxborough Farm Durborough Lower Aisholt Farm Caravan G Site O O D 'S L Triscombe A N W House Quarry E e Luxborough s t (dis) S A Farm o 3 m 5 8 e Quarry r s e (dis) t R a i l w a y B Quarry O A (dis) R P A T H L A N E G ood R E E N 'S Smokeham R H OCK LANE IL Farm L L HIL AK Lower Merridge D O OA BR Rock Farm ANE HAM L SMOKE E D N Crowcombe e A L f Heathfield K Station C O R H OL FO Bishpool RD LA Farm NE N EW Rich's Holford RO AD WEST BAGBOROUGH CP Courtway L L I H S E O H f S H e E OL S FOR D D L R AN E E O N Lambridge H A L Farm E Crowcombe Heathfield L E E R N H N T E K Quarry West Bagborough Kenley (dis) Farm Cricket Ground BIRCHES CORNER E AN Quarry 'S L RD Quarry (dis) FO BIN (dis) D Quarry e f (dis) Tilbury Park Football Pitch Coursley W e s t S Treble's Holford o m e E Quarry L -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Walking Walking

SSDC_walks leaflet-20pp_NOV19.indd 1 leaflet-20pp_NOV19.indd SSDC_walks 15/11/2019 13:03 15/11/2019 At the next crossroads turn right; after about 100m turn left onto a surfaced discoversouthsomerset.com 6 road. Yeovil the to back and gates 4 7 4 7 track past some houses. After the second (white) house bear left and follow 4 7 Walks Norton-sub-Hamdon to Chinnock East Ladies Walk, Montacute Walk, Ladies miles km miles km a signposted footpath between a copse and a ditch. Go over the stile and walk miles km these through Pass old. years 200 along the top of the next fi eld and through the gate at Townsend Farm onto about are these of most trees; mature 2 Coldharbour Lane. Views to the south are superb, with Pen Wood opposite of abundance the to due site wildlife (restricted access now allowed). county a is itself park The 1601. East Coker Parish Walk Hardington Parish Walk Turn left up the farm drive to a road (Penn Lane) and follow the signposted West Coker Parish Walk in family Phelips the by built House, 7 Montacute of view good a is There path across the road to the right of the buildings. Pass next to the buildings Designed by: www.rocketbox.co.uk ©SSDC 2018 ©SSDC www.rocketbox.co.uk by: Designed This walk visits the villages of West Coker and East Coker with hill. steep means Montacute as Hill Hymerford House is reported to be the home of William Dampier a This walk has many spectacular views of South Somerset and Dorset. -

Sol\IERSETSHIRE .. TAUNTON

DIRECTORY.] SOl\IERSETSHIRE .. TAUNTON. 357 • • J. Heathcote M.A. & the Rev. W. G. Fitzgerald hon. Clerk to the Trustees of the Market, Thomas J ames Shepherd, chaplains;- Rev. L. H. P. Maurica M.A. acting chaplain ; Castle green A Co. Capt. H. C. Sweet; B Co. Capt. E. T. Alms; Sergt. Collector of the Market, C. J. Fox, Castle green Major E. Willey, drill instructor Collector of Income & Assessed Taxes, St. Mary Magdalene Parish, William Waterman, 31 Paul street; St. James', TAUNTON UNION~ John Mattocks Chapman, 10 Canon street Board day, fortnightly, wednesday, at 2.go, at the Work Collector of Inland Revenue, Wm. Furze Bickford, Forest house. Collector of Poor Rates for St. Mary Magdalene Without, The Union comprises the following parishes :-Angersleigh, William Henry Wake, Church square; St. Mary :Magda Ash Priors, Bickenhall, Bishops Hull (Within & Without), lene Within, David Poole Hewer, Upper High street; St. Bishops Lydeard, Cheddon Fitzpaine, Churchstanton James Within & Without, John Mattocks Chapman, 10 (Devon), Combe Florey, Corfe, Cothelstone, Creech St. Canon street; Bishops Hull Within & Without, J. l\Iayes, Miehael, Curland, Durston, Halse, Hatch Beauchamp, Bishops Hull Heathfield, Kingston, Lydeard St. Lawrence, North County Analyst, Henry James Alford M.n., F.c.s. 2 :\'Iarl Curry, N orton Fitzwarren, Orchard Portman, Otterford, borough terrace Pitminster, Ruishton, Staplegrove, Staple Fitzpaine, County Surveyor, Charles Edmond Norman, 12 Hammet st Stoke St. Gregory, Stoke St. Mary, Taunton St. James Curator of Somerset Archreological & Natural History (Without & Within), Taunton St. Mary Magdalane (With Society, William Bidgood, The Castle out & Within), Thornfalcon, Thurlbear, Tolland, Trull, Deputy Clerk of the Peace for the. -

BUNYAN STUDIES a Journal of Reformation and Nonconformist Culture

BUNYAN STUDIES A Journal of Reformation and Nonconformist Culture Number 23 2019 Bunyan Studies is the official journal of The International John Bunyan Society www.johnbunyansociety.org www.northumbria.ac.uk/bunyanstudies BUNYAN STUDIES –— A Journal of Reformation and Nonconformist Culture –— Editors W. R. Owens, Open University and University of Bedfordshire Stuart Sim, formerly of Northumbria University David Walker, Northumbria University Associate Editors Rachel Adcock, Keele University Robert W. Daniel, University of Warwick Reviews Editor David Parry, University of Exeter Editorial Advisory Board Sylvia Brown, University of Alberta N. H. Keeble, University of Stirling Vera J. Camden, Kent State University Thomas H. Luxon, Dartmouth College Anne Dunan-Page, Aix-Marseille Université Vincent Newey, University of Leicester Katsuhiro Engetsu, Doshisha University Roger Pooley, Keele University Isabel Hofmeyr, University of the Witwatersrand Nigel Smith, Princeton University Ann Hughes, Keele University Richard Terry, Northumbria University Editorial contributions and correspondence should be sent by email to W. R. Owens at: [email protected] Books for review and reviews should be sent by mail or email to: Dr David Parry, Department of English and Film, University of Exeter, Queen’s Building, The Queen’s Drive, Exeter EX4 4QH, UK [email protected] Subscriptions: Please see Subscription Form at the back for further details. Bunyan Studies is free to members of the International John Bunyan Society (see Membership Form at the back). Subscription charges for non-members are as follows: Within the UK, each issue (including postage) is £10.00 for individuals; £20.00 for institutions. Outside the UK, each issue (including airmail postage) is £12.00/US$20.00 for individuals; £24.00/US$40.00 for institutions. -

Somerset Mobile Library the Mobile Library Visits the Communities Listed Below

Somerset Mobile Library The Mobile Library visits the communities listed below. To find the date of a visit, identify the community and the route letter. Scroll down to the relevant route schedule. The location of each stop is given as well as the dates and times of visits for the current year. Community Day Route Community Day Route A E-F Alcombe FRI L East Brent FRI H Ashcott TUE N East Chinnock TUE E East Coker TUE E B East Lydford THU K Babcary THU C Edington TUE N Badgworth FRI H Evercreech THU K Bagley FRI H Exford FRI D Baltonsborough THU C Barton St. David THU C Beercrocombe THU P G Benter WED J Goathurst WED O Biddisham FRI H Greenham TUE I Blue Anchor FRI L Brent Knoll FRI H H Bridgetown (Exe Valley) TUE A Hardington Mandeville TUE E Bridgwater (Children's Centre) FRI Q Hatch Beauchamp THU P Broadway THU P Hemington MON M Brompton Regis TUE A Hillfarance TUE I Burtle TUE N Holcombe WED J Butleigh THU C I Ilchester WED B C Ilton THU P Cannington THU G Isle Abbots THU P Catcott TUE N Isle Brewers THU P Chantry WED J Chapel Allerton FRI H J-K Charlton Horethorne WED B Keinton Mandeville THU C Chedzoy FRI Q Kilve THU G Chillington WED F Kingston St. Mary WED O Chilton Polden TUE N Chiselborough TUE E L Churchinford WED F Leigh upon Mendip WED J Coleford WED J Lydeard St. Lawrence TUE I Combwich THU G Lympsham FRI H Cotford St Luke TUE I Creech St Michael THU P Crowcombe FRI L Cutcombe FRI D D Doulting THU K Durston WED O Community Day Route Community Day Route M S Merriott TUE E Shapwick TUE N Middlezoy FRI Q Shepton Mallet(Shwgrd) THU K Milton TUE E Shipham FRI H Minehead (Butlins) FRI L Shurton THU G Monksilver FRI L South Barrow WED B Moorlinch FRI Q Southwood THU C Mudford WED B Spaxton WED O Stapley WED F N Stawell FRI Q North Curry WED O Stockland Bristol THU G North Petherton (Stockmoor) FRI Q Stogumber FRI L North Wootton THU K Stogursey THU G Norton St. -

Alexander Popham, M.P. for Taunton, and the Bill for the Prevention of The

ALEXANDER POPHAM, M.P. for Taunton, AND THE BILL FOR THE PREVENTION OF THE GAOL DISTEMPER, 1774. A HYGIENIC RETROSPECT. PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Delivered before the Annual Aleeting of the West Somerset Branch of the British Medical Association at Taunton, on Thursday, June 2Sth, iSg4, BY ARTHUR DURANT WILLCOCKS, M.R.C.S., L.S.A. LONDON : HARRISON AND SONS, ST. MARTIN'S LANE, Printers iti Ordinary to Her Majesty. 1894 At the request of several friends and members of the Association, I have printed the Presidential Address which I had the honour to deliver before the Annual Meeting of the Wsst Somerset Branch of the British Medical Association on June iZth last. I have, at the same time, added in the form of aft Appendix, a chronological table of all outbreaks of so-called Gaol Fever which I have been able to verify down to the end of the eighteenth century. A. D. W. Taunton, September, 1894. — ALEXANDER POPHAM, M.P. FOR Taunton AND THE BILL FOR THE PREVENTION OF THE GAOL DISTEMPER. Gentlemen : I have to thank you for the honour you have conferred upon me in raising me to the post of President of this Branch, and I need hardly assure you that I am deeply sensible of the importance and of the responsibilities of my position. It was well said by the wisest man of old, that as iron sharpeneth iron, so a man sharpeneth the countenance of his friend. When I look around on the keen and friendly countenances assembled here to-day, I feel, therefore, very hopeful, as a comparatively junior member, that my intelli- gence will be considerably sharpened before I come to the end of my tenure of office. -

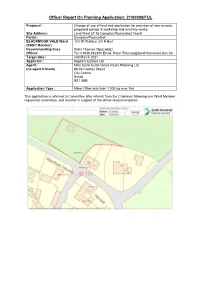

Planning Application 21/00008/FUL

Officer Report On Planning Application: 21/00008/FUL Proposal : Change of use of land and application for provision of new access, proposed garage & workshop and ancillary works. Site Address: Land West Of 18 Compton Pauncefoot Yeovil Parish: Compton Pauncefoot BLACKMOOR VALE Ward Cllr W Wallace Cllr H Burt (SSDC Member) Recommending Case Peter Thomas (Specialist) Officer: Tel: 01935 462350 Email: [email protected] Target date : 2nd March 2021 Applicant : Hopkins Estates Ltd Agent: Miss Coral Curtis Grass Roots Planning Ltd (no agent if blank) 86-88 Colston Street City Centre Bristol BS1 5BB Application Type : Minor Other less than 1,000 sq.m or 1ha This application is referred to Committee after referral from the Chairman following one Ward Member request for committee, and another in support of the officer recommendation. SITE DESCRIPTION AND PROPOSAL The application site compromises a parcel of land which forms part of an agricultural field which is bounded by Compton Road to the south-west and the rear of No. 18 & 19 New Road to the south-east. A septic tank serving six properties from the village is located at the north boundary of the site. The site rises in an easterly direction and forms part of the Compton Pauncefoot Conservation Area. It is within proximity of several listed buildings and non designated heritage assets, including the Grade II* listed church of St Mary and grade II buildings including the Old Rectory and Stable wing. The site also contains a non-designated heritage asset, in the form of earthworks identified in the Somerset Historic Environment Record. -

![Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5807/complete-baronetage-of-1720-to-which-erroneous-statement-brydges-adds-845807.webp)

Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds

cs CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 092 524 374 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924092524374 : Complete JSaronetage. EDITED BY Gr. Xtl. C O- 1^ <»- lA Vi «_ VOLUME I. 1611—1625. EXETER WILLIAM POLLAKD & Co. Ltd., 39 & 40, NORTH STREET. 1900. Vo v2) / .|vt POirARD I S COMPANY^ CONTENTS. FACES. Preface ... ... ... v-xii List of Printed Baronetages, previous to 1900 xiii-xv Abbreviations used in this work ... xvi Account of the grantees and succeeding HOLDERS of THE BARONETCIES OF ENGLAND, CREATED (1611-25) BY JaMES I ... 1-222 Account of the grantees and succeeding holders of the baronetcies of ireland, created (1619-25) by James I ... 223-259 Corrigenda et Addenda ... ... 261-262 Alphabetical Index, shewing the surname and description of each grantee, as above (1611-25), and the surname of each of his successors (being Commoners) in the dignity ... ... 263-271 Prospectus of the work ... ... 272 PREFACE. This work is intended to set forth the entire Baronetage, giving a short account of all holders of the dignity, as also of their wives, with (as far as can be ascertained) the name and description of the parents of both parties. It is arranged on the same principle as The Complete Peerage (eight vols., 8vo., 1884-98), by the same Editor, save that the more convenient form of an alphabetical arrangement has, in this case, had to be abandoned for a chronological one; the former being practically impossible in treating of a dignity in which every holder may (and very many actually do) bear a different name from the grantee. -

Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2

Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2 WWW.SOMERSET.GOV.UK WELCOME TO THE 2ND SOMERSET RIGHTS OF WAY IMPROVEMENT PLAN Public Rights of Way are more than a valuable recreational resource - they are also an important asset in terms of the rural economy, tourism, sustainable transport, social inclusion and health and well being. The public rights of way network is key to enabling residents and visitors alike to access services and enjoy the beauty of Somerset’s diverse natural and built environment. Over the next few years, the focus is going to be chiefly on performing our statutory duties. However, where resources allow we will strive to implement the key priority areas of this 2nd Improvement Plan and make Somerset a place and a destination for enjoyable walking, riding and cycling. Harvey Siggs Cabinet Member Highways and Transport Rights of Way Improvement Plan (1) OVERVIEW Network Assets: This Rights of Way Improvement Plan (RoWIP) is the prime means by which Somerset County • 15,000 gates Council (SCC) will manage the Rights of Way Service for the benefit of walkers, equestrians, • 10,000 signposts cyclists, and those with visual or mobility difficulties. • 11,000 stiles • 1300+ culverts The first RoWIP was adopted in 2006, since that time although ease of use of the existing • 2800+ bridges <6m network has greatly improved, the extent of the public rights of way (PRoW) network has • 400+ bridges >6m changed very little. Although many of the actions have been completed, the Network Assessment undertaken for the first RoWIP is still relevant for RoWIP2. Somerset has one of the There are 5 main aims of RoWIP2: longest rights of way networks in the country – it currently • Raise the strategic profile of the public rights of way network stands at 6138 km.