An Examination of the Improvisatory Style of Herbert Lawrence "Sonny" Greenwich Andrew Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4823C7a9d589da82e72837249d

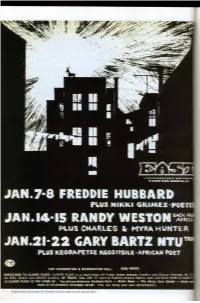

RETURN TO THE EAST BROOKLYN RECLRIMS THE BLRCK RRT FORM KNOWN RS JRZZ I' IIlII£I SCIIII£I • B9 BllSIl MCHBII 'What you're about to hear is not jazz, or some other irrelevant term we allow others 10 use in defining our creation, but the sounds thai are about to saturate your being and serlsitize your soul is the continuing process of nationalist consciousness manifesting its message within the conlext of one of our strongest natural resources: Black music. What is represented on these jams is the crystallization of the role of Black music as a functional organ in the struggle for national liberation.. AJkebu-lan is the unfolding of this progress as mu!>ic-meaoing. It is sound-feeling." KwmbI. >PUI<Irc .... -_. on SUN-Uol his lpOkrn.word innoduuion amounl$ 10 :l m:o.ni- Kwasi Konadu'l r«mt book, Trulh Cru.sJKJ It> tIN &nh rrd:o.iming tlK Black nl form known u WiU RiM Api.., is the delining tome on lhe Ezsr.. h details T for uS/: ali :o.libn:aling. II2l1"P"rti..., vdlic:k. '1M do- lhecompln worIrinV ofhow the organiulion flourished for qurnl <kKript ion ofil :oJ :l -funuion,,1 organ- ckserillQ 1M o>'n adead... 1hc wt and iu primary k>c:o.tion at ,00aver mk of$('lUnd wilhin m.- Ezsr. organiu.ion wdl. MllSic Plac:c in Brooklyn WU n(K just a norefrom or musk hall, bul the blood pumping, mako i. as;"r m dig"". and a w::o.yoflifc.lhc Uhunf Food asan or. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Spilleliste: Åtti Deilige År Med Blue Note Foredrag Oslo Jazz Circle, 14

Spilleliste: Åtti deilige år med Blue Note Foredrag Oslo Jazz Circle, 14. januar 2020 av Johan Hauknes Preludium BLP 1515/16 Jutta Hipp At The Hickory House /1956 Hickory House, NYC, April 5, 1956 Jutta Hipp, piano / Peter Ind, bass / Ed Thigpen, drums Volume 1: Take Me In Your Arms / Dear Old Stockholm / Billie's Bounce / I'll Remember April / Lady Bird / Mad About The Boy / Ain't Misbehavin' / These Foolish Things / Jeepers Creepers / The Moon Was Yellow Del I Forhistorien Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons & Pete Johnson Jumpin' Blues From Spiritals to Swing, Carnegie Hall, NYC, December 23, 1938 BN 4 Albert Ammons - Chicago In Mind / Meade "Lux" Lewis, Albert Ammons - Two And Fews Albert Ammons Chicago in Mind probably WMGM Radio Station, NYC, January 6, 1939 BN 6 Port of Harlem Seven - Pounding Heart Blues / Sidney Bechet - Summertime 1939 Sidney Bechet, soprano sax; Meade "Lux" Lewis, piano; Teddy Bunn, guitar; Johnny Williams, bass; Sidney Catlett, drums Summertime probably WMGM Radio Station, NYC, June 8, 1939 Del II 1500-serien BLP 1517 Patterns in Jazz /1956 Gil Mellé, baritone sax; Eddie Bert [Edward Bertolatus], trombone; Joe Cinderella, guitar; Oscar Pettiford, bass; Ed Thigpen, drums The Set Break Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, April 1, 1956 BLP 1521/22 Art Blakey Quintet: A Night at Birdland Clifford Brown, trumpet; Lou Donaldson, alto sax; Horace Silver, piano; Curly Russell, bass; Art Blakey, drums A Night in Tunisia (Dizzy Gillespie) Birdland, NYC, February 21, 1954 BLP 1523 Introducing Kenny Burrell /1956 Tommy Flanagan, -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Matt Andersen Will Be Performing at the Maple Blues Awards

January 2018 www.torontobluessociety.com Published by the TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY since 1985 [email protected] Vol 34, No 1 PHOTO BY SEAN SISK BY PHOTO Matt Andersen will be performing at the Maple Blues Awards CANADIAN PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #40011871 Blues Booster Rob Bowman Event Listings John’s Blues Picks Top Blues Loose Blues News and More TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY 910 Queen St. W. Ste. B04 Toronto, Canada M6J 1G6 Tel. (416) 538-3885 Toll-free 1-866-871-9457 Email: [email protected] Website: www.torontobluessociety.com MapleBlues is published monthly by the Toronto Blues Society ISSN 0827-0597 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Derek Andrews (President), Jon Arnold, Lucie Dufault (Vice-President), Carol Flett (Secretary), Sarah French, Jamie MacDonald (Vice-President), Lori Murray, Ed Parsons, Paul Sanderson, Mike Smith, Earl Tucker, John Valenteyn (Executive), David Walker (Treasurer) Musicians Advisory Council: Brian Blain, Gary Kendall, Samantha Martin, Lily Sazz, Mark Stafford, Jenie Thai, Suzie Vinnick,Ken Whiteley Fundraising Committee: Derek Andrews, Jon Arnold, Jamie MacDonald, Mike Smith, Sarah Gardiner Volunteer & Membership Committee: Lucie Dufault, Sarah French, Mike Smith, Ed Parsons, Carol Flett Fundraising Consultant: Sarah Gardiner Grants Officer: Barbara Isherwood Office Staff: Hüma Üster (Office Manager) Amanda Rheaume (Project Manager) Publisher/Editor-in-Chief: Derek Andrews Managing Editor: Brian Blain [email protected] Contributing Editors: John Valenteyn, Alice Sellwood, Erin McCallum, Carol Flett Listings Coordinator: Janet Alilovic Mailing and Distribution: Ed Parsons Become a member of the Toronto Blues Society, and get connected with Canada's premier blues events, releases, and our great blues community. With the help of members, donors and volunteers, Advertising: Dougal Bichan the TBS is able to put on great events such as The Maple Blues Awards, Blues in the Schools, Guitar [email protected] and Harmonica Workshops, the New Talent Search, and the always popular Women's Blues Revue. -

Depaul Jazz Workshop Dana Hall, Director

Ronald Caltabiano, DMA, Dean Tuesday, March 10, 2020 • 7:00 PM DEPAUL JAZZ WORKSHOP Dana Hall, director Mary A. Dempsey and Philip H. Corboy Jazz Hall 2330 North Halsted Street • Chicago Tuesday, March 10, 2020 • 7:00 PM Dempsey Corboy Jazz Hall DEPAUL JAZZ WORKSHOP Dana Hall, director PROGRAM TO BE SELECTED FROM THE FOLLOWING: Victor Feldman; arr. Earl MacDonald Joshua Jackie McLean; arr. Earl MacDonald Appointment in Ghana Brooks Bowman; arr. Earl MacDonald East of the Sun (and West of the Moon) John Birks ‘Dizzy’ Gillespie; arr. Earl MacDonald Woody ’n’ You Charlie Parker; arr. Marty Paich Donna Lee Clark Sommers Chance Encounter DEPAUL JAZZ WORKSHOP • MARCH 10, 2020 BIOGRAPHIES Born in Brooklyn, New York, drummer Dana Hall has been an important musician on the international music scene since 1992. After completing his education in aerospace engineering at Iowa State University, he received his Bachelor of Music degree from William Paterson College in Wayne, New Jersey and, in 1999, his Masters degree in composition and arranging from DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois. He is presently a distinguished Special Trustees Fellow completing his PhD in ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago. Mr. Hall previously taught at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign before joining DePaul University as Associate Professor of Jazz Studies and Ethnomusicology in 2012. The list of exceptional artists that Mr. Hall has performed, toured, and/or recorded with directly reflects the diverse and varied approaches of his music-making in -

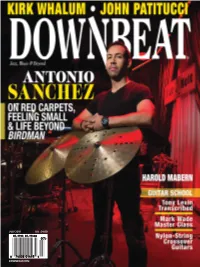

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Proquest Dissertations

Drawing as Architectural Construction By William Aaron Klassen A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE M.ARCH (Professional) Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario (April 18, 2008) © copyright 2008, William Aaron Klassen Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40620-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40620-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Master Dance

THE MASTER DANCE of TISZIJI MUÑOZ THE AUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY PART THREE – DOCTOR OF MUSIC by Nancy Muñoz & Lydia R. Lynch the illumination society presents: The Master Dance of Tisziji Muñoz The Authorized Biography Part Three Doctor of Music Written By Nancy Muñoz (Subhuti Kshanti Sangha-Gita-Ma) & Lydia R. Lynch (Sama-dhani) Initial Typing & Editing By Jacob Lettrick (Jinpa) Revisions By Karin Walsh (Tahmpa Tse Trin) & Janet Veale (Kshima) Cover Photo by James J. Kriegsmann “The Master Dances to Its Own Music.” —Tisziji I The Master Dance of Tisziji Muñoz: The Authorized Biography, Part Three. By Nancy Muñoz & Lydia Lynch. Copyright © 1990 by Tisziji Muñoz & The Il- lumination Society, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the authors. The Illumination Society, Inc. Newburgh, NY USA www.heartfiresound.com The Master Dance of Tisziji Muñoz: The Authorized Biography Part Three Doctor of Music By Nancy Muñoz (Subhuti Kshanti Sangha-Gita-Ma) & Lydia R. Lynch (Sama-dhani) Copyright © July 1990 by Tisziji Muñoz & The Illumination Society, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the authors. II The Master Dance of Tisziji Muñoz: The Authorized Biography, Part Three. By Nancy Muñoz & Lydia Lynch. Copyright © 1990 by Tisziji Muñoz & The Il- lumination Society, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the authors. -

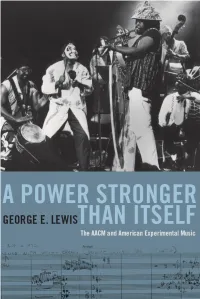

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

I a COMPARATIVE STUDY of the JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES of CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, and FREDDIE HUBBARD an EXAMINATION of IMPROVISA

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES OF CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, AND FREDDIE HUBBARD AN EXAMINATION OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE FROM 1953-1964 by JAMES HARRISON MOORE Bachelor of Music, West Virginia University, 2003 Master of Music, University of the Arts, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by James Harrison Moore It was defended on March 29, 2012 Committee Members: Dean L. Root, Professor, Music Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Music Lawrence Glasco, Professor, History Dissertation Advisor: Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music ii Copyright © by James Harrison Moore 2012 iii Nathan T. Davis, PhD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES OF CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, AND FREDDIE HUBBARD: AN EXAMINATION OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYE FROM 1953-1964. James Harrison Moore, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This study is a comparative examination of the musical lives and improvisational styles of jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown, and two prominent jazz trumpeters whom historians assert were influenced by Brown—Donald Byrd and Freddie Hubbard. Though Brown died in 1956 at the age of 25, the reverence among the jazz community for his improvisational style was so great that generations of modern jazz trumpeters were affected by his playing. It is widely said that Brown remains one of the most influential modern jazz trumpeters of all time. In the case of Donald Byrd, exposure to Brown’s style was significant, but the extent to which Brown’s playing was foundational or transformative has not been examined. -

Suggested Listening - Jazz Artists 1

SUGGESTED LISTENING - JAZZ ARTISTS 1. TRUMPET - Nat Adderley, Louis Armstrong, Chet Baker, Terrance Blanchard, Lester, Bowie, Randy Brecker, Clifford Brown, Don Cherry, Buck Clayton, Johnny Coles, Miles Davis, Kevin Dean, Kenny Dorham, Dave Douglas, Harry Edison, Roy Eldridge, Art Farmer, Dizzy Gillespie, Bobby Hackett, Tim Hagans, Roy Hargrove, Phillip Harper,Tom Harrell, Eddie Henderson, Terumaso Hino, Freddie Hubbard, Ingrid Jensen, Thad Jones, Booker Little, Joe Magnarelli, John McNeil, Wynton Marsalis, John Marshall, Blue Mitchell, Lee Morgan, Fats Navarro, Nicholas Payton, Barry Ries, Wallace Roney, Jim Rotondi, Carl Saunders, Woody Shaw, Bobby Shew, John Swana, Clark Terry, Scott Wendholt, Kenny Wheeler 2. SOPRANO SAX - Sidney Bechet, Jane Ira Bloom, John Coltrane, Joe Farrell, Steve Grossman, Christine Jensen, David Liebman, Steve Lacy, Chris Potter, Wayne Shorter 3. ALTO SAX - Cannonball Adderley, Craig Bailey, Gary Bartz, Arthur Blythe, Richie Cole, Ornette Coleman, Steve Coleman, Paul Desmond, Eric Dolphy, Lou Donaldson, Paquito D’Rivera, Kenny Garrett, Herb Geller, Bunky Green, Jimmy Greene, Antonio Hart, John Jenkins, Christine Jensen, Eric Kloss, Lee Konitz, Charlie Mariano, Jackie McLean, Roscoe Mitchell, Frank Morgan, Lanny Morgan, Lennie Niehaus, Greg Osby, Charlie Parker, Art Pepper, Bud Shank, Steve Slagel, Jim Snidero, James Spaulding, Sonny Stitt, Bobby Watson, Steve Wilson, Phil Woods, John Zorn 4. TENOR SAX - George Adams, Eric Alexander, Gene Ammons, Bob Berg, Jerry Bergonzi, Don Braden, Michael Brecker, Gary Campbell,