Parliament, the Courts and the NZBORA.Pdf (286.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Care Alliance Submission to Justice Select Committee FINAL March 6

Submission of the Care Alliance Charitable Trust to the Justice Select Committee consideration of the End of Life Choice Bill 6 March 2018 Introduction 1. This submission is made on behalf of the Care Alliance Charitable Trust (Care Alliance). 2. The trustees of Care Alliance are John Kleinsman, PhD (Chair), Sinead Donnelly, MD, FRCPI, FRACP, FAChPM (Deputy Chair) and Michael Hallagan (Treasurer). The Secretary is Professor Emeritus Peter Thirkell, PhD, Honorary Fellow ANZMAC. 3. The Care Alliance is a coalition of Groups and individuals that has been workinG toGether since 2012 to nurture better conversations about dyinG in Aotearoa New Zealand. All members share an understandinG that a compassionate and ethical response to sufferinG does not include euthanasia and assisted suicide. 4. OrGanisations that are members include: • ANZSPM Aotearoa (the New Zealand chapter of the Australian & New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine) • Christian Medical Fellowship • Euthanasia-Free New Zealand • Family First New Zealand • Hospice New Zealand • Lutherans for Life • New Zealand Health Professionals Alliance • Not Dead Yet Aotearoa • Pacific Leaders Forum • Palliative Care Nurses New Zealand • The Nathaniel Centre • The Salvation Army in New Zealand 5. Individuals in the Care Alliance are Quakers, Catholics, Protestants, Buddhists, agnostics and atheists. We never arGue the question of intentionally endinG the lives of patients from a faith perspective because we simply wouldn’t be able to agree what it was. 6. Our focus is on the practical effects of the Bill presently before this Committee, and particularly its impact on the most vulnerable members of our society should it become law. In short, we arGue that the provisions of this Bill are unable to achieve their stated purpose without placinG other people within the community at siGnificant risk, includinG the risk of wronGful death. -

![Print/Download PDF [182KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5297/print-download-pdf-182kb-665297.webp)

Print/Download PDF [182KB]

No 235 House of Representatives Supplementary Order Paper Tuesday, 21 May 2019 End of Life Choice Bill Proposed amendments Louisa Wall, in Committee, to move the following amendments: Clause 1 amended In clause 1 (page 2, line 3) replace “the End of Life Choice Act 2017” with “the Court Consent to Physician Assisted Dying Act 2019”. Clause 3 replaced Replace clause 3 (page 2, line 9 to page 4, line 13) with: 3 Interpretation In this Act, unless the context requires another meaning,— assisted dying, in relation to a person, means— (a) the administration by a medical practitioner of a lethal dose of medication to the person to relieve the person’s suffering by hastening death; or (b) with the support of a medical practitioner, the self-adminis- tration by the person of a lethal dose of medication to relieve their suffering by hastening death. medical practitioner means a health practitioner who— (a) is, or is deemed to be, registered with the Medical Council of New Zealand continued by section 114(1)(a) of the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 as a practi- tioner of the profession of medicine; and (b) holds a current practising certificate 1 Proposed amendments to SOP No 235 End of Life Choice Bill minister means the Minister of the Crown who is responsible for the administration of this Act— (a) under the authority of a warrant; or (b) under the authority of the Prime Minister ministry means the Ministry of Justice palliative care means health services delivered to a person with a terminal illness that aims to optimise -

Law and Life

Law and Life The Lecretia Seales Memorial Lecture Delivered at the New Zealand Parliament 29 August 2016 by Rt Hon Sir Geoffrey Palmer QC* ___________________________ * Barrister, Distinguished Fellow, Victoria University of Wellington, Faculty of Law and Centre for Public Law, Global Affiliated Professor, University of Iowa. I am grateful to Professor Bill Atkin, Andrew Butler, Catherine Marks, Professor R S Clark and Dr Warren Young for comments on a draft of this lecture and to Scarlet Roberts for research assistance. None of them is responsible for its content. 2 Lecretia’s Plight Lecretia Seales died of a cancerous brain tumour in Wellington on 3 June 2015. She was 42. Employed by the Law Commission as a senior legal and policy adviser for eight years, Lecretia had an abiding interest and competence in the field of law reform. She lived in Karori with her devoted husband Matt Vickers and their Abyssinian cat Ferdinand. I feel privileged to have known Lecretia well, both when I was President of the Law Commission and earlier when she worked with me at the law firm Chen, Palmer and Partners, public law specialists. Lecretia was a lawyer of high quality and she had a passion for the law. She hailed from Tauranga where her parents Shirley and Larry still live. She loved cooking and dancing. She had the gifts of friendship and empathy. I have met few people as determined and strong as she was. In the case she brought in the High Court concerning her impending death one witness described her personality as “young, bright, independent, perfectionist.” I concur. -

For Personal Stories See

1 EDITORIAL - PHONY WAR HEADS INTO LAST BATTLE We are in what David Seymour calls the “phony war” as Parliament’s Justice Committee ploughs through 37,000 submissions on his End of Life Choice Bill and most MPs focus on other things, knowing they do not have to vote on it for at least six more months. If you look at the submissions as they are posted on Parliament’s website, it has reluctantly to be said it appears to be a war that at this stage we are not winning. For as we know, our opponents have divine motivation to fight enlightened legislation that would give the terminally sick the option of relief from their suffering. Encouraged by a barrage of lies and misinformation fed them weekly from the pulpit they are flooding the committee with a litany of ignorant claims about the measure. It does not matter that they are often illiterate – and rarely show any sign that the writers have actually read the bill – they believe the committee can be persuaded that it is a numbers game. “They will say anything and stop at nothing to create fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) over the bill,” Seymour said in a message for this Newsletter. And he warned that the weight of the opposition’s campaign will test the resolve of MPs who may decide it is all just too difficult. “That’s why it is essential that EoLC members maintain a counterweight to the intense lobbying that is going on from the FUD campaign,” Seymour said. Noting that every reliable and scientific opinion poll on the issue shows an overwhelming majority of voters want medically-assisted dying to be legalised, he said: “MPs need to be reminded that for every shrill anti, there are five people who think it is time for change and choice. -

Insight Article Print Format

Legal update - The right to die in New Zealand - Seales v Attorney General Alastair Hercus, Peter Chemis, Hamish Kynaston, Alastair Sherriff, Natasha Wilson, Catherine Miller 21 August 2015 Introduction The recent High Court case of Seales v Attorney-General has generated much discussion about the law on assisted dying in New Zealand. This update sets out a brief overview of the relevant law and discusses the Seales v Attorney-General case, including what the case might mean for the future. A brief overview of the law The act of suicide is not a crime in New Zealand. However, certain provisions of the Crimes Act address suicide and assisted dying. Key amongst these is section 179, which provides: Every one is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years who: a) incites, counsels, or procures any person to commit suicide, if that person commits or attempts to commit suicide in consequence thereof; or b) aids or abets any person in the commission of suicide. The law of homicide is also relevant, as a deliberate act to assist a person's death will likely amount to culpable homicide (section 160). Importantly, section 63 also states that no one has a right to consent to their death and section 164 provides that someone may be criminally responsible for another's death even if their conduct served only to hasten that death. In the particular context of assisted dying, the "doctrine of double effect" is also relevant. That doctrine is yet to be fully tested in the New Zealand courts but in the English case of Airedale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] AC 789 (HL), Lord Goff described the principle as: . -

February 2018 END-OF-LIFE CHOICE SOCIETY of NEW ZEALAND INC Issue 49 Member of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies

February 2018 END-OF-LIFE CHOICE SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND INC Issue 49 Member of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies EDITORIAL - 2018 IS MAKE OR BREAK YEAR We have entered a critical new year for the cause we conservatives - are in a minority but they are bent on have been fighting four decades so far. fighting a campaign blatantly built on lies and Whether it will prove to be a happy one remains misinformation to stop us and overseas experience to be seen. shows they are funded by wealthy church coffers. For while we made history in December when We expect a better deal from Parliament's Parliament voted for the first time to allow an assisted Justice Select Committee than we received from the dying Bill to progress beyond the first stage, we can biased group that last considered the issue, but we have no doubts about the struggle ahead to win the have only until February 20 to make formal ultimate human right of the 21st century. submissions and we need all our members to make It has never been more important for every their voices heard. member of our society to do whatever they can to The committee then has until mid-September promote the right to die with dignity and persuade our to make its recommendations to Parliament before all politicians to go on and pass an enlightened law. MPs vote again on whether New Zealand will join 110 This is a make or break year. It has been 15 million Americans and millions more in Canada, years since Parliament last tackled the issue and if we Europe, South America and Australia with the right to miss out on this opportunity there will be another long allow our terminally ill who are suffering intolerably to gap before it faces it again. -

Lecretia Seales 1973 - 2015 Rip

12 July 2015 VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND INC Issue 40 LECRETIA SEALES 1973 - 2015 RIP Rod Emmerson’s cartoon appeared in the NZ Herald on June 6, the day after Lecretia Seales died. I sent a message on behalf of VESNZ complimenting him on it, saying: “You touched the hearts of hundreds if not thousands with this poignant drawing”, and requested his permission to reprint it in this Newsletter. Emmerson replied: “There has been an enormous - positive - response to this cartoon” and sent a high-resolution copy to reproduce at no charge. We thank him. David Barber, Editor. WILL LAW CHANGE BE HER LEGACY? Lecretia Seales died at the age of 42 just over into the issue of medically assisted dying. four years after her inoperable brain tumour While she failed in a bid to persuade was diagnosed. Her tragic case moved the a High Court judge to let her doctor help nation, undoubtedly helping VESNZ gather her die without fear of prosecution, she 8975 signatures on an historic petition and she managed to work until taking sick leave in leaves a powerful legacy in the shape of the March and did not resign her job until New Zealand Parliament’s first public inquiry Continued on Page 2 End-of-Life Choice Newsletter - for personal stories see www.ves.org.nz/ourstories 43 May 20, being spared the pain and indignity of at their first reading, meaning they were a long period of unendurable suffering. “In the denied committee hearings that would have end, Lecretia was fortunate that her death attracted public submissions. -

Voluntary Euthanasia and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act a Critical Analysis of the Seales V Attorney-General Decision

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington CAMERON LAING Voluntary Euthanasia and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act A Critical Analysis of the Seales v Attorney-General Decision LAWS522: PUBLIC LAW Submitted for the LLB (Honours) Degree Faculty of Law Victoria University of Wellington 2015 2 Abstract: The recent decision of Seales v Attorney-General clarified the law surrounding voluntary euthanasia in New Zealand. In addition to seeking declaratory judgment from the High Court as to the proper interpretation of certain provisions of the Crimes Act 1961, Lecretia Seales sought two declarations regarding sections 8 and 9 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. Specifically, that insofar as certain provisions of the Crimes Act restrict a person with a terminal and incurable illness from seeking life- ending medical assistance, the Crimes Act is inconsistent with a person’s rights not to be deprived of life and not to be subjected to torture or cruel treatment. This paper critiques Justice Collins’ conclusions that sections 8 and 9 of the Bill of Rights Act were not breached in Ms Seales’ tragic circumstances. Further, it argues that sections 8 and 9 of the Bill of Rights Act should extend to circumstances where people are suffering from terminal and incurable illnesses and recognise a right to seek life-ending medical assistance. Finally, the paper critiques the methodology used by the courts in New Zealand when assessing whether rights-infringing legislation is justified pursuant to section 5 of the Bill of Rights Act, and ultimately concludes that the courts should always query whether rights-infringing legislation serves a purpose sufficiently important to justify infringement of human rights. -

Critical Year Starts with Personal Attacks From

12 February 2016 VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND INC Issue 42 CRITICAL YEAR STARTS WITH PERSONAL ATTACKS FROM RATTLED OPPONENTS by David Barber, Editor What promises to be a critical year for the campaign outrageous eXample of a red herring”; Jansen linked to achieve the end-of-life choice law change that at Matt and VESNZ with a proposal by euthanasia least three-quarters of New Zealanders want began campaigners in the Netherlands to allow all elderly with signs that our opponents are increasingly people access to a death pill, regardless of their nervous about the prospect of us succeeding. medical condition. As the February 1 deadline for submissions to Assuming Matt’s attendance at the Parliament’s first public inquiry into the issue neared, Euthanasia 2016 international conference in they stepped up their usual litany of lies and Amsterdam in May - although Matt had not made up misinformation and moved into personal attacks. his mind whether to attend an invitation to speak Top of their hate list was Lecretia Seales, the gutsy there - showed "what a slippery slope the so-called brain cancer victim who last year disappointingly right to die really is", Jansen said. failed to persuade a High Court judge to let her The “slippery slope” is a scare tactic phrase doctor end her suffering with a planned and peaceful opponents regularly use in the absence of reason to death. frighten people who have not made up their minds Opponents of physician-assisted dying were about physician-assisted dying. incensed when the New Zealand Herald, the Matt rightly said it was "simply fallacious" to country’s largest newspaper, named Lecretia their assume his presence at the conference would be an New Zealander of the Year for 2015, saying: “She automatic endorsement of the views of organisers or was brave and inspiring, sharing something as others attending. -

![SEALES V ATTORNEY-GENERAL [2015] NZHC 1239 [4 June 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2093/seales-v-attorney-general-2015-nzhc-1239-4-june-2015-3992093.webp)

SEALES V ATTORNEY-GENERAL [2015] NZHC 1239 [4 June 2015]

ORDER PROHIBITING PUBLICATION OF THIS JUDGMENT UNTIL 3.00PM ON 5 JUNE 2015. IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND WELLINGTON REGISTRY CIV-2015-485-000235 [2015] NZHC 1239 UNDER The Declaratory Judgments Act 1908 and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 BETWEEN LECRETIA SEALES Plaintiff AND ATTORNEY-GENERAL Defendant Hearing: 25-27 May 2015 Counsel: A S Butler with C J Curran, C M Marks, M L Campbell and E J Watt for Plaintiff Mr M Heron QC, Solicitor-General with P T Rishworth QC, E J Devine and Y Moinfar for Defendant M S R Palmer QC and J S Hancock for Human Rights Commission V E Casey and M S Smith for Care Alliance K G Davenport QC with A H Brown and L M K E Almoayed for Voluntary Euthanasia Society of New Zealand (Incorporated) Judgment: 4 June 2015 JUDGMENT OF COLLINS J Summary of judgment [1] Ms Seales is dying from a brain tumour.1 She is 42 years old and may have only a short time to live.2 1 The names of Ms Seales’ principal oncologist, another oncologist who has treated her and her doctor have been suppressed. Affidavit of Ms Seales’ principal oncologist, 2 April 2015 at [7]- [8]; Ms Seales’ principal oncologist has explained Ms Seales has “diffuse astrocytoma ... with elements of an oligodendroglioma. This combination is often abbreviated to ‘oligoastrocytoma’. Both astrocytoma … and oligodendroglioma … grow diffusely and infiltrate the brain”. 2 Second affidavit of Ms Seales’ principal oncologist, 22 May 2015 at [6]; Ms Seales can now SEALES v ATTORNEY-GENERAL [2015] NZHC 1239 [4 June 2015] [2] Ms Seales wants to have the option of determining when she dies. -

![SEALES V ATTORNEY-GENERAL [2015] NZHC 1239 [4 June 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9108/seales-v-attorney-general-2015-nzhc-1239-4-june-2015-4609108.webp)

SEALES V ATTORNEY-GENERAL [2015] NZHC 1239 [4 June 2015]

ORDER PROHIBITING PUBLICATION OF THIS JUDGMENT UNTIL 3.00PM ON 5 JUNE 2015. IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND WELLINGTON REGISTRY CIV-2015-485-000235 [2015] NZHC 1239 UNDER The Declaratory Judgments Act 1908 and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 BETWEEN LECRETIA SEALES Plaintiff AND ATTORNEY-GENERAL Defendant Hearing: 25-27 May 2015 Counsel: A S Butler with C J Curran, C M Marks, M L Campbell and E J Watt for Plaintiff Mr M Heron QC, Solicitor-General with P T Rishworth QC, E J Devine and Y Moinfar for Defendant M S R Palmer QC and J S Hancock for Human Rights Commission V E Casey and M S Smith for Care Alliance K G Davenport QC with A H Brown and L M K E Almoayed for Voluntary Euthanasia Society of New Zealand (Incorporated) Judgment: 4 June 2015 JUDGMENT OF COLLINS J Summary of judgment [1] Ms Seales is dying from a brain tumour.1 She is 42 years old and may have only a short time to live.2 1 The names of Ms Seales’ principal oncologist, another oncologist who has treated her and her doctor have been suppressed. Affidavit of Ms Seales’ principal oncologist, 2 April 2015 at [7]- [8]; Ms Seales’ principal oncologist has explained Ms Seales has “diffuse astrocytoma ... with elements of an oligodendroglioma. This combination is often abbreviated to ‘oligoastrocytoma’. Both astrocytoma … and oligodendroglioma … grow diffusely and infiltrate the brain”. 2 Second affidavit of Ms Seales’ principal oncologist, 22 May 2015 at [6]; Ms Seales can now SEALES v ATTORNEY-GENERAL [2015] NZHC 1239 [4 June 2015] [2] Ms Seales wants to have the option of determining when she dies. -

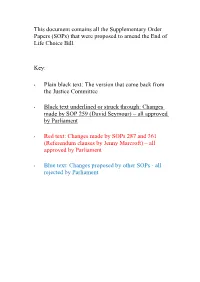

(Sops) That Were Proposed to Amend the End of Life Choice Bill

This document contains all the Supplementary Order Papers (SOPs) that were proposed to amend the End of Life Choice Bill. Key: • Plain black text: The version that came back from the Justice Committee • Black text underlined or struck through: Changes made by SOP 259 (David Seymour) – all approved by Parliament • Red text: Changes made by SOPs 287 and 361 (Referendum clauses by Jenny Marcroft) – all approved by Parliament • Blue text: Changes proposed by other SOPs - all rejected by Parliament Proposed amendments to End of Life Choice Bill SOP No 259 Explanatory note This Supplementary Order Paper sets out amendments to the End of Life Choice Bill. The following substantive amendments are made to the Bill: • a purpose clause is inserted (new clause 2A): • definitions of approved form, attending nurse practitioner, conscientious objec- tion, medication, and nurse practitioner are inserted (clause 3): • the definition of independent medical practitioner is amended to require the medical practitioner to have held a practising certificate for at least the previ- ous 5 years, to ensure that an experienced medical practitioner gives the second opinion as to whether a person is eligible for assisted dying (clause 3): • the definition of person who is eligible for assisted dying is amended so that a person who has a grievous and irremediable medical condition that is not a ter- minal illness likely to end the person’s life within 6 months will not be eligible for assisted dying (clause 4(1)(c) replaced): • the competence of a person who wishes