Untitled Performance Event That Incorporated Paintings by Robert Rauschenberg and Music by David Tudo R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudolf Laban in the 21St Century: a Brazilian Perspective

DOCTORAL THESIS Rudolf Laban in the 21st Century: A Brazilian Perspective Scialom, Melina Award date: 2015 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Rudolf Laban in the 21st Century: A Brazilian Perspective By Melina Scialom BA, MRes Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Dance University of Roehampton 2015 Abstract This thesis is a practitioner’s perspective on the field of movement studies initiated by the European artist-researcher Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) and its particular context in Brazil. Not only does it examine the field of knowledge that Laban proposed alongside his collaborators, but it considers the voices of Laban practitioners in Brazil as evidence of the contemporary practices developed in the field. As a modernist artist and researcher Rudolf Laban initiated a heritage of movement studies focussed on investigating the artistic expression of human beings, which still reverberates in the work of artists and scholars around the world. -

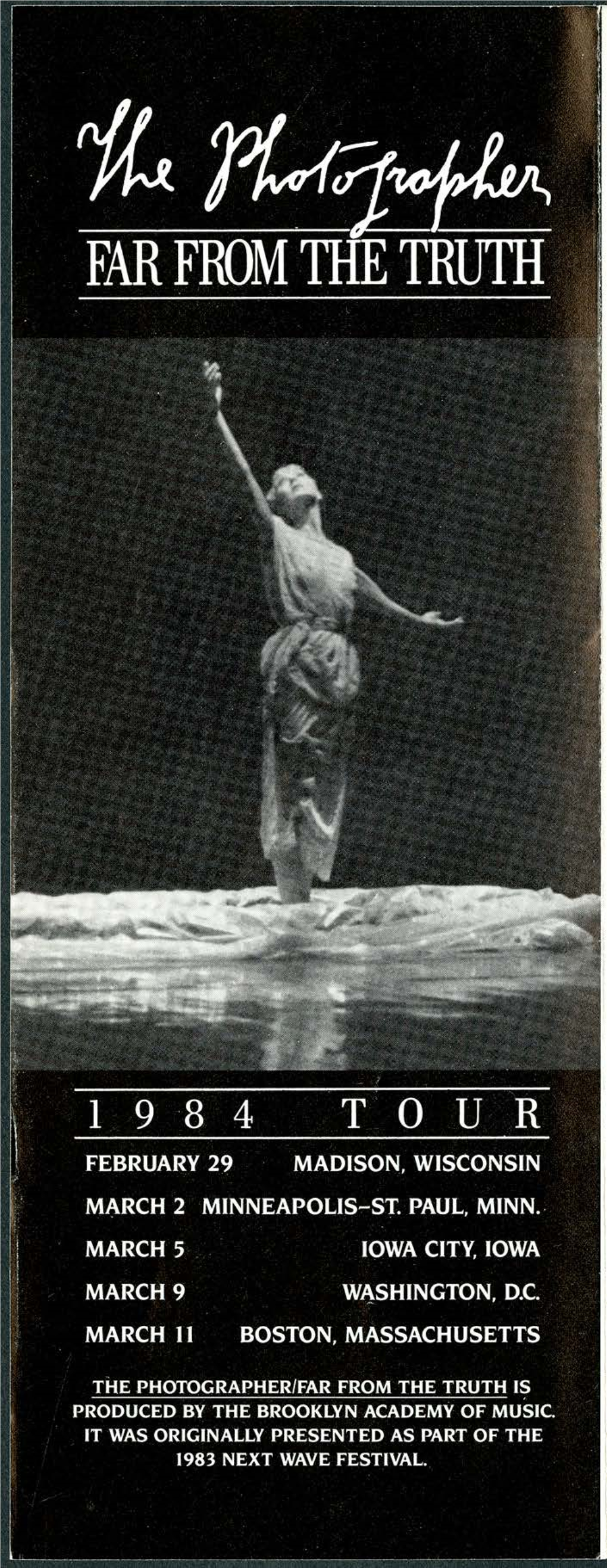

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

Tese Maria Joao Castro.Pdf

A Dança e o Poder ou o Poder da Dança: Diálogos e Confrontos no século XX Maria João Castro Tese de Doutoramento em História da Arte Contemporânea Dezembro, 2013 1 Ao meu Pai, mecenas incondicional da minha vontade de conhecimento. Ao Pedro, pela cumplicidade do caminho deixando-me respirar... 2 AGRADECIMENTOS Inúmeras pessoas contribuíram de forma decisiva para que esta investigação chegasse a bom termo. O grupo inclui professores, colegas, amigos e desconhecidos que se cruzaram ao longo do projecto e que se dispuseram a ajudar na clareza e compreensão das informações. A primeira expressão de agradecimento cabe à Professora Doutora Margarida Acciaiuoli, por ter aceitado orientar esta tese com todo o rigor, determinação e empenho que a caracterizam, bem como pelo contributo que as suas críticas, sempre pertinentes e cordiais, provocaram na elaboração deste trabalho. A José Sasportes, pela forma como se disponibilizou para co-orientar esta investigação, pela vastíssima informação que me confiou, pelo estímulo e confiança, pela ampliação do campo de referências e pela cumplicidade na partilha da paixão pela dança, o que constituiu um inestimável e insubstituível auxílio. A todos os meus professores de dança com os quais aprendi de variadas maneiras como a dança nos modifica, nomeadamente a Liliane Viegas, João Hydalgo e Myriam Szabo, bem como aos meus colegas a amigos que, de variadíssimas formas, contribuíram para o desenvolvimento deste projecto, nomeadamente a Luísa Cardoso, António Laginha e Miguel Leal. À Vera de Vilhena, pela cuidada revisão do texto e por, com as suas sugestões, me ter ajudado a crescer na escrita. À Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, pela bolsa que me atribuiu, permitindo-me a dedicação exclusiva e a liberdade de poder estar continuamente dedicada a este trabalho. -

Made in America: the Cultural Legacy of Jazz Dance Artist Gus Giordano Linda Sabo Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 Made in America: the cultural legacy of jazz dance artist Gus Giordano Linda Sabo Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Dance Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sabo, Linda, "Made in America: the cultural legacy of jazz dance artist Gus Giordano" (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 178. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Made in America: The cultural legacy of jazz dance artist Gus Giordano by linda Sabo A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (literature) Major Professor: Nina Miller Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1998 ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Linda Saba has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signature redacted for privacy Major Professor Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy iii DEDICATION To Fritz, for giving me the time ... and the rope To Gus, for giving me his blessing and for sharing the dance iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 I. ENCOUNTERING THE SPIRIT OF JAZ2 DANCE 5 The Jazz Aesthetic: Its Derivations 9 The Jazz Aesthetic: Its Singularity 32 II. -

An Historical Perspective on Lucinda Childs' Calico Mingling

arts Article Towards an Embodied Abstraction: An Historical Perspective on Lucinda Childs’ Calico Mingling (1973) Lou Forster 1,2 1 Centre de Recherche sur les Arts et le Langage, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 75006 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Institut National D’histoire de L’art, 75002 Paris, France Abstract: In the 1970s, choreographer Lucinda Childs developed a reductive form of abstraction based on graphic representations of her dance material, walking, and a specific approach towards its embodiment. If her work has been described through the prism of minimalism, this case study on Calico Mingling (1973) proposes a different perspective. Based on newly available archival documents in Lucinda Childs’s papers, it traces how track drawing, the planimetric representation of path across the floor, intersected with minimalist aesthetics. On the other hand, it elucidates Childs’s distinctive use of literacy in order to embody abstraction. In this respect, the choreographer’s approach to both dance company and dance technique converge at different influences, in particular modernism and minimalism, two parallel histories which have been typically separated or opposed. Keywords: reading; abstraction; minimalism; technique; collaboration; embodiment; geometric abstraction; modernism 1. Introduction On the 7 December 1973, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, four women Citation: Forster, Lou. 2021. performed Calico Mingling, the latest group piece by Lucinda Childs. The soles of white Towards an Embodied Abstraction: sneakers, belonging to Susan Brody, Judy Padow, Janice Paul and Childs, resonated on the An Historical Perspective on Lucinda wood floor of the Madison Avenue, building with a sustained tempo. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1979

National Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1979. Respectfully, Livingston L. Biddle, Jr. Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. February 1980 1 Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 The Agency and Its Functions 4 National Council on the Arts 5 Programs Deputy Chairman’s Statemen~ 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 50 Folk Arts 84 Literature 100 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 118 Museum 140 Music 172 Opera-Musical Theater 202 Special Projects 212 Theater 222 Visual Arts 240 Policy and Planning Challenge Grants 272 Evaluation 282 International/Fellows 283 Research 286 Special Constituencies 288 Office for Partnership Executive Director’s Statement 296 Education (Artists-in-Schools) 299 Federal-State Partnership (State Programs) 305 Intergovernmental Activities 312 Financial Summary 314 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 315 Chairman’s Statement A Common Cause for the Arts isolated rural coraraunities to the barrios and Perhaps nothing is raore enviable--or raore ghettoes of our inner cities. The dreara---that daunting--than the opportunity to raake a prac of access for all Araericans to the best in art- tical reality out of a visionary dreara. I happen is becoraing reality. to have this unusual privilege. As special assist But reality, as we all know, is a thorny ant to Senator Claiborne Pell frora 1963 to thing, with catches, snares and tangles. -

Paper 7 Modern Dance and Its Development In

PAPER 7 MODERN DANCE AND ITS DEVELOPMENT IN THE WORLD AFTER 1960 (USA, EUROPE, SEA) MODERN EXPERIMENTS IN INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE, NEW WAVE AFTER 1930, UDAYSHANKAR AND LATER CONTEMPORARY, CREATIVE ARTISTS MODULE 16 MODERN DANCE IN GERMANY AND FRANCE According to historians, modern dance has two main birthplaces: Europe (Germany specifically) and the United States of America. Although it evolves as a concert dance form, it has no direct roots in any ballet companies, schools, or artists. Germany is the birthplace of modern dance, theatre realism, and both dance and theatre production dramaturgy. The country’s history is interwoven with its dance, music, art, literature, architecture, religion, and history. In addition to the direct dance training and rehearsals, students will see performances and visit museums and other cultural sites in one of Europe’s most exciting capitals. Contemporary dance in Germany is characterized by a vibrant globalization and combines elements from drama, performance and musical theatre. It is the story of three passionate choreographers and their colleagues who created European modern dance in the 20th century despite the storms of war and oppression. It begins with Rudolph Laban, innovator and guiding force, and continues with the careers of his two most gifted and influential students, Mary Wigman and 1 Kurt Jooss. Included are others who made significant contributions: Hanya Holm, Sigurd Leeder, Gret Palucca, Berthe Trumpy, Vera Skoronel, Yvonne Georgi and Harold Kreutzberg. The German strain of contemporary dance as it has manifested itself in the United States is usually overlooked if not unacknowledged. There is general agreement that modern dance, a 20th-century phenomenon, has been dominated by Americans. -

![Hanya Holm Archives [Videorecording] V0386](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4230/hanya-holm-archives-videorecording-v0386-4134230.webp)

Hanya Holm Archives [Videorecording] V0386

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8p84989 No online items Guide to the Hanya Holm Archives [videorecording] V0386 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives March 2012 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Hanya Holm V0386 1 Archives [videorecording] V0386 Language of Material: Undetermined Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Hanya Holm archives [videorecording] Identifier/Call Number: V0386 Physical Description: 1.5 Linear Feet22 videotapes (VHS) Date (inclusive): 1985 Biographical/Historical note Hanya Holm (born March 3, 1893, Worms, Germany – died November 3, 1992, New York City) is known as one of the "Big Four" founders of American modern dance. She was a dancer, choreographer, and above all, a dance educator. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Hanya Holm Archives (V0386). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Publication Rights All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/pubserv/permissions.html. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. -

Expressions of Form and Gesture in Ausdruckstanz

EXPRESSIONS OF FORM AND GESTURE IN AUSDRUCKSTANZ, TANZTHEATER, AND CONTEMPORARY DANCE by TONJA VAN HELDEN B.A., University of New Hampshire, 1998 M.A., University of Colorado, 2003 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Program of Comparative Literature 2012 This thesis entitled: Expressions Of Form And Gesture In Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater, And Contemporary Dance written by Tonja van Helden has been approved for the Comparative Literature Graduate Program __________________________________________ Professor David Ferris, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Assistant Professor Ruth Mas, Committee member ____________________________________________ Professor Jennifer Peterson, Committee member ____________________________________________ Professor Henry Pickford, Committee member ____________________________________________ Professor Davide Stimilli, Committee member Date ________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. van Helden, Tonja (Ph. D., Comparative Literature, Comparative Literature Graduate Program) Expressions Of Form And Gesture In Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater, And Contemporary Dance Thesis directed by Professor David Ferris My dissertation examines the historical trajectory of Ausdruckstanz (1908-1936) from its break with Renaissance court ballet up through its transmission into Tanztheater and contemporary styles of postmodern dance. The purpose of this study is to examine the different modes of expression as indicated by the character, form, style, and concept of Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater and contemporary dance. Through a close analysis of select case studies, each chapter provides a critical analysis of the stylistic innovations and conceptual problems evidenced by the choreographies from each movement. -

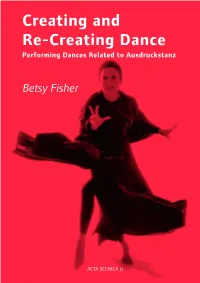

Creating and Re-Creating Dance Performing Dances Related to Ausdruckstanz

Creating and Re-Creating Dance Performing Dances Related to Ausdruckstanz Betsy Fisher ACTA SCENICA 12 Creating and Re-Creating Dance Performing dances related to Ausdruckstanz Betsy Fisher ACTA SCENICA 12 Näyttämötaide ja tutkimus Teatterikorkeakoulu - Scenkonst och forskning - Teaterhögskolan - Scenic art and research - Theatre Academy Betsy Fisher Creating and Re-Creating Dance Performing dances related to Ausdruckstanz written thesis for the artistic doctorate in dance Theatre Academy, Department of Dance and Theatre Pedagogy Publisher: Theatre Academy © Theatre Academy and Betsy Fisher Front and back cover photos: Carl Hefner Cover and lay-out: Tanja Nisula ISBN: 952-9765-31-2 ISSN: 1238-5913 Printed in Yliopistopaino, Helsinki 2002 To Hanya Holm who said, “Can do.” And to Ernest Provencher who said, “I do.” Contents Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 9 Preface 11 Introduction 13 Preparation: Methodology 19 Rehearsal: Directors 26 Discoveries: Topics in Reconstruction 43 Performance: The Call is “Places”– an analysis from inside 75 Creating from Re-Creating: Thicket of Absent Others 116 Connections and Reflections 138 Notes 143 References 150 Index 157 Abstract Performance Thesis All aspects of my research relate to my work in dance reconstruction, performance, and documentation. Concerts entitled eMotion.s: German Lineage in Contemporary Dance and Thicket of Absent Others constitute the degree performance requirements for an artistic doctorate in dance and were presented in Studio-Theater Four at The Theater Academy of Finland. eMotion.s includes my performance of solos choreographed by Mary Wigman, Dore Hoyer, Marianne Vogelsang, Hanna Berger, Rosalia Chladek, Lotte Goslar, Hanya Holm, Alwin Nikolais, Murray Louis, and Beverly Blossom. These choreographers share a common artistic link to Ausdruckstanz (literally Expression Dance). -

The Strange Commodity of Cultural Exchange: Martha Graham and the State Department on Tour, 1955-1987

The Strange Commodity of Cultural Exchange: Martha Graham and the State Department on Tour, 1955-1987 Lucy Victoria Phillips Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Lucy Victoria Phillips All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Strange Commodity of Cultural Exchange: Martha Graham and the State Department on Tour, 1955-1987 Lucy Victoria Phillips The study of Martha Graham's State Department tours and her modern dance demonstrates that between 1955 and 1987 a series of Cold Wars required a steady product that could meet "informational" propaganda needs over time. After World War II, dance critics mitigated the prewar influence of the German and Japanese modernist artists to create a freed and humanist language because modern dance could only emerge from a nation that was free, and not from totalitarian regimes. Thus the modern dance became American, while at the same time it represented a universal man. During the Cold War, the aging of Martha Graham's dance, from innovative and daring to traditional and even old-fashioned, mirrored the nation's transition from a newcomer that advertised itself as the postwar home of freedom, modernity, and Western civilization to an established power that attempted to set international standards of diplomacy. Graham and her works, read as texts alongside State Department country plans, United States Information Agency publicity, other documentary evidence, and oral histories, reveal a complex matrix of relationships between government agencies and the artists they supported, as well as foundations, private individuals, corporations, country governments, and representatives of business and culture. -

To Dance Beyond Yourself: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’S

© COPYRIGHT by Rachel Thornton 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TO DANCE BEYOND YOURSELF: ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER’S WOODCUT PRINTS OF MARY WIGMAN BY Rachel Thornton ABSTRACT Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s legacy as a founding member of Die Brücke (The Bridge), and one of the leading figures of German Expressionism, has made his work of the period between 1905 and 1918 the subject of considerable scholarly attention. Less often considered are the works Kirchner produced after leaving Germany for Switzerland immediately following the end of World War I. The works he made during this later period of his career are generally dismissed as stylistically deficient, derivative, and out of step with the current developments of the artistic avant-garde. Refuting this view of Kirchner’s post-Brücke work, my thesis will examine two series of Kirchner’s dance-themed woodcut prints created in the years 1926 and 1933; works inspired by acclaimed Expressionist dancer Mary Wigman. As I will show, the stylistic elements of the two images in the later series, decidedly different from the dance-themed works that he created in 1926, cannot be interpreted entirely within the context of Expressionism. I interpret these works by relating Kirchner’s interpretation of Wigman’s Ausdruckstanz (Expressionist dance) to his interest in Georges Bataille’s concept of the informe (formlessness), disseminated widely in the French Surrealist magazine Documents. My analysis of Kirchner’s dance imagery centers on the collaborative, cooperative model that Wigman modeled at her school of dance, founded in 1920. I suggest that the negotiation of the dichotomy between individuation and association that Kirchner witnessed in Wigman’s school provided a framework through which he investigated Surrealist concepts as well as his ii own Expressionist past.