Exploring Sikh Traditions and Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan Was Suspended by President General Musharaff in March Last Year Leading to a Worldwide Uproar Against This Act

A Coup against Judicial Independence . Special issue of the CJEI Report (February, 2008) ustice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the twentieth Chief Justice of Pakistan was suspended by President General Musharaff in March last year leading to a worldwide uproar against this act. However, by a landmark order J handed down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Justice Chaudhry was reinstated. We at the CJEI were delighted and hoped that this would put an end to the ugly confrontation between the judiciary and the executive. However our happiness was short lived. On November 3, 2007, President General Musharaff suspended the constitution and declared a state of emergency. Soon the Pakistan army entered the Supreme Court premises removing Justice Chaudhry and other judges. The Constitution was also suspended and was replaced with a “Provisional Constitutional Order” enabling the Executive to sack Chief Justice Chaudhry, and other judges who refused to swear allegiance to this extraconstitutional order. Ever since then, the judiciary in Pakistan has been plunged into turmoil and Justice Chaudhry along with dozens of other Justices has been held incommunicado in their homes. Any onslaught on judicial independence is a matter of grave concern to all more so to the legal and judicial fraternity in countries that are wedded to the rule of law. In the absence of an independent judiciary, human rights and constitutional guarantees become meaningless; the situation capable of jeopardising even the long term developmental goals of a country. As observed by Viscount Bryce, “If the lamp of justice goes out in darkness, how great is the darkness.” This is really true of Pakistan which is presently going through testing times. -

Kartarpur Corridor November 2019 | Edition 1

NOVEMBER 2019 | EDITION 1 ECONOMIC SOCIAL POLICY REGIONAL GOVERNANCE POLICY INTEGRATION KARTARPUR CORRIDOR (written by Amisha) Kartarpur marks the most significant and constructive phase in the life of Guru Nanak Dev JI. The name Kartarpur means “Place of God”. During the 1947 partition of India the region got divided across India and Pakistan. The Radcliff line awarded the shakargarh tehsil on the right bank of the river including Kartarpur to Pakistan and the Gurdaspur tehsil on the left bank of Ravi to India. The wait is now over, pilgrims who used to stand on platforms with folded hands and binoculars to catch a clear view of the holy Kartarpur Gurudwara can literally now cross the border and visit the shrine. This is the first time since partition in 1947 that the border between the two Punjabis, apart from the crossing at wagah-Attari, is being breached in peacetime. NOVEMBER 1, 2019 CPRG NEWSLETTER EDITION 1 The India and Pakistan open Kartarpur corridor on the occasion of Guru Nanak Dev ji’s Parkash Purab. This has fulfilled long waited wish of more than 6 million Sikhs. This corridor has been designed to facilitate easy access for the pilgrims visiting the shrine. It includes hotels, commercial areas, apartments, parking lots, border facility area, power grid station and an information center. A bridge over the Ravi connects the Indian side at Dera, Baba Nanak with kartarpur on Pakistani side. The Indians visiting the shrine wouldn’t require any visa but their passport and would undergo some security and obtain special permission. On a daily basis 5000 pilgrims can register and get a chance to visit their holy place. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

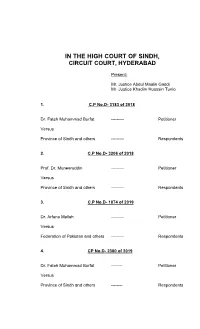

View of Above, It Is Observed That Instant Petition (C.P

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, CIRCUIT COURT, HYDERABAD Present: Mr. Justice Abdul Maalik Gaddi Mr. Justice Khadim Hussain Tunio 1. C.P No.D- 3183 of 2018 Dr. Fateh Muhammad Burfat --------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others --------- Respondents 2. C.P No.D- 3206 of 2018 Prof. Dr. Muneeruddin --------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others --------- Respondents 3. C.P No.D- 1874 of 2019 Dr. Arfana Mallah --------- Petitioner Versus Federation of Pakistan and others --------- Respondents 4. CP No.D- 2380 of 2019 Dr. Fateh Muhammad Burfat -------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others -------- Respondents 2 Date of Hearings : 6.02.2020, 03.03.2020 & 10.03.2020 Date of order : 10.03.2020 Mr. Rafique Ahmed Kalwar Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. Nos.D- 3183 of 2018, 2380 of 2019 and for Respondent No.5 in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019. Mr. Shabeer Hussain Memon, Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. No.D- 3206 of 2018. Mr. K.B. Lutuf Ali Laghari Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019 and intervener in C.P. No.D- 2380 of 2019. Mr. Allah Bachayo Soomro, Additional Advocate General, Sindh alongwith Jawad Karim AD (Legal) ACE Jamshoro on behalf of ACE Sindh. Mr. Kamaluddin Advocate also appearing for Respondent No.5 in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019. None present for respondent No.1 (Federation of Pakistan) in C.P. No.D-1874/2019. O R D E R ABDUL MAALIK GADDI, J.- By this common order, we intend to dispose of aforementioned four constitutional petitions together as a common question of facts and law is involved in all these petitions as well as the subject matter is also interconnected. -

Sikhism Reinterpreted: the Creation of Sikh Identity

Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications Senior Theses Student Publications 4-16-2014 Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Brittany Fay Puller Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/seniortheses Part of the Asian History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Puller, Brittany Fay, "Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity" (2014). Senior Theses. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Abstract The iS kh identity has been misinterpreted and redefined amidst the contemporary political inclinations of elitist Sikh organizations and the British census, which caused the revival and alteration of Sikh history. This thesis serves as a historical timeline of Punjab’s religious transitions, first identifying Sikhism’s emergence and pluralism among Bhakti Hinduism and Chishti Sufism, then analyzing the effects of Sikhism’s conduct codes in favor of militancy following the human Guruship’s termination, and finally recognizing the identity-driven politics of colonialism that led to the partition of Punjabi land and identity in 1947. Contemporary practices of ritualism within Hinduism, Chishti Sufism, and Sikhism were also explored through research at the Golden Temple, Gurudwara Tapiana Sahib Bhagat Namdevji, and Haider Shaikh dargah, which were found to share identical features of Punjabi religious worship tradition that dated back to their origins. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Pakistan Elects a New President

ISAS Brief No. 292 – 2 August 2013 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Pakistan Elects a New President Shahid Javed Burki1 Abstract With the election, on 30 July 2013, of Mamnoon Hussain as Pakistan’s next President, the country has completed the formal aspects of the transition to a democratic order. It has taken the country almost 66 years to reach this stage. As laid down in the Constitution of 1973, full executive authority is now in the hands of the prime minister who is responsible to the elected national assembly and will not hold power at the pleasure of the president. With the transition now complete, will the third-time Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, succeed in pulling the country out of the deep abyss into which it has fallen? Only time will provide a full answer to this question. Having won a decisive victory in the general election on 11 May 2013 and having been sworn into office on 5 June, Mian Mohammad Nawaz Sharif settled the matter of the presidency on 30 July. This office had acquired great importance in Pakistan’s political evolution. Sharif had problems with the men who had occupied this office during his first two terms as Prime Minister – in 1990-93 and 1997-99. He was anxious that this time around the 1 Mr Shahid Javed Burki is Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. -

Supreme Court of the United States ───── ─────

NO. 19-1388 In the Supreme Court of the United States ───── ───── JASON SMALL, Petitioner, v. MEMPHIS LIGHT, GAS & WATER, Respondent. ───── ───── On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ───── ───── BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE MUSLIM ADVOCATES AND THE SIKH COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ───── ───── HORVITZ & LEVY LLP MUSLIM ADVOCATES JEREMY B. ROSEN NIMRA H. AZMI Counsel of Record P.O. BOX 34440 SCOTT P. DIXLER WASHINGTON, D.C. 20043 JACOB M. MCINTOSH THE SIKH COALITION 3601 W. OLIVE AVE., 8TH FL. AMRITH KAUR AAKRE BURBANK, CA 91505 CINDY NESBIT (818) 995-0800 50 BROAD ST., SUITE 504 [email protected] NEW YORK, NY 10004 Counsel for Amici Curiae July 17, 2020 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 2 ARGUMENT ................................................................ 5 I. This Court should grant review and apply the ordinary meaning of “undue hardship” to Title VII’s accommodation scheme. ..................... 5 A. The de minimis rule is textually indefensible and strips Title VII of any meaningful mandate to accommodate religion. .......................................................... 5 B. A plain reading of “undue hardship” creates a workable rule that aligns with other accommodation regimes. ..................... 7 II. The de minimis rule causes serious harm to religious minorities, as shown by the experiences of Muslim and Sikh employees. ....... 9 A. Muslim employees are routinely denied accommodations for trivial reasons under the de minimis standard. .............................. 9 B. Sikh employees face exclusion from employment and segregation in the workplace under the de minimis rule. ........ 15 C. The accommodations denied to Muslim and Sikh employees under Title VII are available in other contexts under other statutes. -

The Khalsa and the Non-Khalsa Within the Sikh Community in Malaysia

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 8 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Khalsa and the Non-Khalsa within the Sikh Community in Malaysia Aman Daima Md. Zain1, Jaffary, Awang2, Rahimah Embong 1, Syed Mohd Hafiz Syed Omar1, Safri Ali1 1 Faculty of Islamic Contemporary Studies, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA) Malaysia 2 Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3222 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3222 Abstract In the pluralistic society of Malaysia, the Sikh community are categorised as an ethnic minority. They are considered as a community that share the same religion, culture and language. Despite of these similarities, they have differences in terms of their obedience to the Sikh practices. The differences could be recognized based on their division into two distintive groups namely Khalsa and non-Khalsa. The Khalsa is distinguished by baptism ceremony called as amrit sanskar, a ceremony that makes the Khalsa members bound to the strict codes of five karkas (5K), adherence to four religious prohibitions and other Sikh practices. On the other hand, the non-Khalsa individuals have flexibility to comply with these regulations, although the Sikhism requires them to undergo the amrit sanskar ceremony and become a member of Khalsa. However the existence of these two groups does not prevent them from working and living together in their religious and social spheres. This article aims to reveal the conditions of the Sikh community as a minority living in the pluralistic society in Malaysia. The method used is document analysis and interviews for collecting data needed. -

Harpreet Singh

FROM GURU NANAK TO NEW ZEALAND: Mobility in the Sikh Tradition and the History of the Sikh Community in New Zealand to 1947 Harpreet Singh A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, The University of Otago, 2016. Abstract Currently the research on Sikhs in New Zealand has been defined by W. H. McLeod’s Punjabis in New Zealand (published in the 1980s). The studies in this book revealed Sikh history in New Zealand through the lens of oral history by focussing on the memory of the original settlers and their descendants. However, the advancement of technology has facilitated access to digitised historical documents including newspapers and archives. This dissertation uses these extensive databases of digitised material (combined with non-digital sources) to recover an extensive, if fragmentary, history of South Asians and Sikhs in New Zealand. This dissertation seeks to reconstruct mobility within Sikhism by analysing migration to New Zealand against the backdrop of the early period of Sikh history. Covering the period of the Sikh Gurus, the eighteenth century, the period of the Sikh Kingdom and the colonial era, the research establishes a pattern of mobility leading to migration to New Zealand. The pattern is established by utilising evidence from various aspects of the Sikh faith including Sikh institutions, scripture, literature, and other historical sources of each period to show how mobility was indigenous to the Sikh tradition. It also explores the relationship of Sikhs with the British, which was integral to the absorption of Sikhs into the Empire and continuity of mobile traditions that ultimately led them to New Zealand. -

Pashaura Singh Chair Professor and Saini Chair in Sikh Studies Department of Religious Studies 2026 CHASS INTN Building 900 University Avenue Riverside, CA 92521

Pashaura Singh Chair Professor and Saini Chair in Sikh Studies Department of Religious Studies 2026 CHASS INTN Building 900 University Avenue Riverside, CA 92521 6th Dr. Jasbir Singh Saini Endowed Chair in Sikh and Punjabi Studies Conference (May 3-4, 2019) Celebrating Guru Nanak: New Perspectives, Reassessments and Revivification ABSTRACTS 1. “No-Man’s-Land: Fluidity between Sikhism and Islam in Partition Literature and Film” Dr. Sara Grewal, Assistant Professor, Department of English Faculty of Arts & Science MacEwan University Room 6-292 10700 – 104 Ave NW Edmonton, AB T5J 4S2 Canada While the logic of (religious) nationalism operative during Partition resulted in horrific, widespread violence, many of the aesthetic responses to Partition have focused on the linkages between religious communities that predated Partition, and in many cases, even continued on after the fact. Indeed, Sikhism and Islam continue to be recognized by many artists as mutually imbricated traditions in the Indian Subcontinent—a tradition cultivated from Mardana’s discipleship with Guru Nanak to the present day—despite the communalism that has prevailed since the colonial interventions of the nineteenth century. By focusing on the fluidity of religious and national identity, artistic works featuring Sikh and Muslim characters in 1947 highlight the madness of Partition violence in a society previously characterized by interwoven religious traditions and practices, as well as the fundamentally violent, exclusionary logic that undergirds nationalism. In my paper, I will focus particularly on two texts that explore these themes: Saadat Hasan Manto’s short story Phone 951-827-1251 Fax 951-827-3324 “Toba Tek Singh” and Sabiha Sumar’s Khamosh Pani.