Psilocybe Subaeruginosa (Cleland 1927) Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strážovské Vrchy Mts., Resort Podskalie; See P. 12)

a journal on biodiversity, taxonomy and conservation of fungi No. 7 March 2006 Tricholoma dulciolens (Strážovské vrchy Mts., resort Podskalie; see p. 12) ISSN 1335-7670 Catathelasma 7: 1-36 (2006) Lycoperdon rimulatum (Záhorská nížina Lowland, Mikulášov; see p. 5) Cotylidia pannosa (Javorníky Mts., Dolná Mariková – Kátlina; see p. 22) March 2006 Catathelasma 7 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY OF FUNGI Lycoperdon rimulatum, a new Slovak gasteromycete Mikael Jeppson 5 Three rare tricholomoid agarics Vladimír Antonín and Jan Holec 11 Macrofungi collected during the 9th Mycological Foray in Slovakia Pavel Lizoň 17 Note on Tricholoma dulciolens Anton Hauskknecht 34 Instructions to authors 4 Editor's acknowledgements 4 Book notices Pavel Lizoň 10, 34 PHOTOGRAPHS Tricholoma dulciolens Vladimír Antonín [1] Lycoperdon rimulatum Mikael Jeppson [2] Cotylidia pannosa Ladislav Hagara [2] Microglossum viride Pavel Lizoň [35] Mycena diosma Vladimír Antonín [35] Boletopsis grisea Petr Vampola [36] Albatrellus subrubescens Petr Vampola [36] visit our web site at fungi.sav.sk Catathelasma is published annually/biannually by the Slovak Mycological Society with the financial support of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Permit of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak rep. no. 2470/2001, ISSN 1335-7670. 4 Catathelasma 7 March 2006 Instructions to Authors Catathelasma is a peer-reviewed journal devoted to the biodiversity, taxonomy and conservation of fungi. Papers are in English with Slovak/Czech summaries. Elements of an Article Submitted to Catathelasma: • title: informative and concise • author(s) name(s): full first and last name (addresses as footnote) • key words: max. 5 words, not repeating words in the title • main text: brief introduction, methods (if needed), presented data • illustrations: line drawings and color photographs • list of references • abstract in Slovak or Czech: max. -

CRISTIANE SEGER.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ CRISTIANE SEGER REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO GÊNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BRASIL CURITIBA 2016 CRISTIANE SEGER REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO GÊNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BRASIL Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Botânica, área de concentração em Taxonomia, Biologia e Diversidade de Algas, Liquens e Fungos, Setor de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Botânica. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Vagner G. Cortez CURITIBA 2016 '«'[ir UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ UFPR Biológicas Setor de Ciências Biológicas ***** Programa de Pos-Graduação em Botânica .*•* t * ivf psiomD* rcD í?A i 0 0 p\» a u * 303a 2016 Ata de Julgamento da Dissertação de Mestrado da pos-graduanda Cristiane Seger Aos 13 dias do mês de maio do ano de 2016, as nove horas, por meio de videoconferência, na presença cia Comissão Examinadora, composta pelo Dr Vagner Gularte Cortez, pela Dr* Paula Santos da Silva e pela Dr1 Sionara Eliasaro como titulares, foi aberta a sessão de julgamento da Dissertação intitulada “REVISÃO TAXONÓMICA DO GÊNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BRASIL” Apos a apresentação perguntas e esclarecimentos acerca da Dissertação, a Comissão Examinadora APROVA O TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO do{a) aluno(a) Cristiane Seger Nada mais havendo a tratar, encerrou-se a sessão da qual foi lavrada a presente ata, que, apos lida e aprovada, foi assinada pelos componentes da Comissão Examinadora Dr Vagr *) Dra, Paula Santos da Stlva (UFRGS) Dra Sionara Eliasaro (UFPR) 'H - UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANA UfPR , j í j B io lo g ic a s —— — — ——— Setor de Ciências Biologicas *• o ' • UrPK ----Programa- de— Pós-Graduação em Botânica _♦ .»• j.„o* <1 I ‘’Hl /Dl í* Ui V* k P, *U 4 Titulo Mestre em Ciências Biológicas - Área de Botânica Dissertação “REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO GÉNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BR ASIL” . -

Stropharia Caerulea Kreisel 1979 Le Chapeau Est Visqueux À L’Humidité, Bleu Verdâtre Décolorant En Jaunâtre, Et La Marge Ornée De Légers Flocons Blancs

13,90 11,55 8,66 10,43 Stropharia caerulea Kreisel 1979 Le chapeau est visqueux à l’humidité, bleu verdâtre décolorant en jaunâtre, et la marge ornée de légers flocons blancs. La cuticule sèche paraît lisse. Systématique Division Basidiomycètes Classe Agaricomycètes Ordre Agaricales Famille Strophariacées Les lames sont adnées à échancrées, crème, puis beige rosé, enfin brun chocolat clair. Détermination L’arête est concolore, caractéristique Les lames adnées à échancrées et la sporée brun déterminante. violacé orientent vers le Genre Stropharia. La sporée est brune . Avec la clé de Marcel Bon, DM 129, suivre : 1a Couleur vert-bleu, 2b Spores < 10 µm Section Stropharia Une confusion est possible avec Stropharia aeruginosa, 3a Espèces moyennes 5-7 cm +/- charnues, qui possède une arête blanche stérile, vert-bleu jaunissant, Le stipe est recouvert d’un voile caulinaire 4b Lames avec arête concolore, nombreuses floconneux blanc se terminant par un un anneau membraneux plus persistant, chrysocystides anneau fragile et fugace teinté de brun par de nombreuses cheilocystides clavées Stropharia caerulea les spores sur sa face supérieure. et très peu de chrysocystides sur l’arête. Les nombreuses chrysocystides de l’arête émergent au milieu de cellules clavées. Elles sont lagéniformes, étirées au sommet plus ou moins longuement sans toutefois être mucronées, et contiennent une vacuole assez importante. Les chrysocystides sécrètent une matière amorphe qui remplit leur vacuole. Cette masse est incolore puis devient jaune et enfin orangée avec l’âge et dans les solutions basiques comme l’ammoniaque ou la potasse. C’est ainsi que la vacuole paraît incolore ou jaune pâle dans l’eau, jaune très vif dans l’ammoniaque et orangée dans le rouge congo ammoniacal. -

Olympic Mushrooms 4/16/2021 Susan Mcdougall

Olympic Mushrooms 4/16/2021 Susan McDougall With links to species’ pages 206 species Family Scientific Name Common Name Agaricaceae Agaricus augustus Giant agaricus Agaricaceae Agaricus hondensis Felt-ringed Agaricus Agaricaceae Agaricus silvicola Forest Agaric Agaricaceae Chlorophyllum brunneum Shaggy Parasol Agaricaceae Chlorophyllum olivieri Olive Shaggy Parasol Agaricaceae Coprinus comatus Shaggy inkcap Agaricaceae Crucibulum laeve Common bird’s nest fungus Agaricaceae Cyathus striatus Fluted bird’s nest Agaricaceae Cystoderma amianthinum Pure Cystoderma Agaricaceae Cystoderma cf. gruberinum Agaricaceae Gymnopus acervatus Clustered Collybia Agaricaceae Gymnopus dryophilus Common Collybia Agaricaceae Gymnopus luxurians Agaricaceae Gymnopus peronatus Wood woolly-foot Agaricaceae Lepiota clypeolaria Shield dapperling Agaricaceae Lepiota magnispora Yellowfoot dapperling Agaricaceae Leucoagaricus leucothites White dapperling Agaricaceae Leucoagaricus rubrotinctus Red-eyed parasol Agaricaceae Morganella pyriformis Warted puffball Agaricaceae Nidula candida Jellied bird’s-nest fungus Agaricaceae Nidularia farcta Albatrellaceae Albatrellus avellaneus Amanitaceae Amanita augusta Yellow-veiled amanita Amanitaceae Amanita calyptroderma Ballen’s American Caesar Amanitaceae Amanita muscaria Fly agaric Amanitaceae Amanita pantheriana Panther cap Amanitaceae Amanita vaginata Grisette Auriscalpiaceae Lentinellus ursinus Bear lentinellus Bankeraceae Hydnellum aurantiacum Orange spine Bankeraceae Hydnellum complectipes Bankeraceae Hydnellum suaveolens -

![[Censored by Critic]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7275/censored-by-critic-467275.webp)

[Censored by Critic]

Official press statement, from a university spokeswoman, regarding the Critic magazines that went missing. [CENSORED BY CRITIC] AfterUniversity Proctor Dave Scott received information yesterday that copies of this week’s Critic magazine were requested to be removed from the Hospital and Dunedin Public Library foyers, the Campus Watch team on duty last night (Monday) removed the rest of the magazines from stands around the University. The assumption was made that, copies of the magazine also needed to be removed from other public areas, and hence the Proctor made this decision. This was an assumption, rightly or wrongly, that this action needed to be taken as the University is also a public place, where non-students regularly pass through. The Proctor understood that the reason copies of this week’s issue had been removed from public places, was that the cover was objectionable to many people including children who potentially might be exposed to it. Today, issues of the magazine, which campus watch staff said numbered around 500 in total, could not be recovered from a skip on campus, and this is regrettable. “I intend to talk to the Critic staff member tomorrow, and explain what has happened and why,” says Mr Scott. The Campus Watch staff who spoke to the Critic Editor today, they were initially unaware of. yesterday’s removal of the magazines. The University has no official view on the content of this week’s magazine. However, the University is aware that University staff members, and members of the public, have expressed an opinion that the cover of this issue was degrading to women. -

Forest Fungi in Ireland

FOREST FUNGI IN IRELAND PAUL DOWDING and LOUIS SMITH COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development Arena House Arena Road Sandyford Dublin 18 Ireland Tel: + 353 1 2130725 Fax: + 353 1 2130611 © COFORD 2008 First published in 2008 by COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development, Dublin, Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from COFORD. All photographs and illustrations are the copyright of the authors unless otherwise indicated. ISBN 1 902696 62 X Title: Forest fungi in Ireland. Authors: Paul Dowding and Louis Smith Citation: Dowding, P. and Smith, L. 2008. Forest fungi in Ireland. COFORD, Dublin. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of COFORD. i CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................v Réamhfhocal...........................................................................................................vi Preface ....................................................................................................................vii Réamhrá................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...............................................................................................ix -

Mushrumors the Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 20 Issue 3 September - November 2009

MushRumors The Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 20 Issue 3 September - November 2009 2009 Mushroom Season Blasts into October with a Flourish A Surprising Turnout at the Annual Fall Show by Our Fungal Friends, and a Visit by David Arora Highlighted this Extraordinary Year for the Northwest Mushroomers On the heels of a year where the weather in Northwest Washington could be described as anything but nor- mal, to the surprise of many, include yours truly, it was actually a good year for mushrooms and the Northwest Mushroomers Association shined again at our traditional fall exhibit. The members, as well as the mushrooms, rose to the occasion, despite brutal conditions for collecting which included a sideways driving rain (which we photo by Pam Anderson thought had come too late), and even a thunderstorm, as we prepared to gather for the greatly anticipated sorting of our catch at the hallowed Bloedel Donovan Community Building. I wondered, not without some trepidation, about what fungi would actually show up for this years’ event. Buck McAdoo, Dick Morrison, and I had spent several harrowing hours some- what lost in the woods off the South Pass Road in a torrential downpour, all the while being filmed for posterity by Buck’s step-son, Travis, a videographer creating a documentary about mushrooming. I had to wonder about the resolve of our mem- bers to go forth in such conditions in or- In This Issue: Fabulous first impressions: Marjorie Hooks der to find the mush- David Arora Visits Bellingham crafted another artwork for the centerpiece. -

Wood Chip Fungi: Agrocybe Putaminum in the San Francisco Bay Area

Wood Chip Fungi: Agrocybe putaminum in the San Francisco Bay Area Else C. Vellinga Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 Koshland Hall, Berkeley CA 94720-3102 [email protected] Abstract Agrocybe putaminum was found growing on wood chips in central coastal California; this appears to be the first record for North America. A short description of the species is given. Its habitat plus the characteristics of wood chip denizens are discussed. Wood chips are the fast food of the fungal world. The desir- able wood is exposed, there is a lot of it, and often the supply is replenished regularly. It is an especially good habitat for mush- room species that like it hot because a thick layer of wood chips is warmed relative to the surrounding environment by the activity of bacteria and microscopic fungi (Brown, 2003; Van den Berg and Vellinga, 1998). Thirty years ago wood chips were a rarity, but nowadays they are widely used in landscaping and gardening. A good layer of chips prevents weeds from germinating and taking over, which means less maintenance and lower costs. Chips also diminish evaporation and keep moisture in the soil. Trees and shrubs are often shredded and dumped locally, but there is also long-dis- tance transport of these little tidbits. Barges full of wood mulch cruise the Mississippi River, and trucks carry the mulch from city to city. This fast food sustains a steady stream of wood chip fungi that, as soon as they are established, fruit in large flushes and are suddenly everywhere. The fungi behave a bit like morels after a Figure 1. -

80130Dimou7-107Weblist Changed

Posted June, 2008. Summary published in Mycotaxon 104: 39–42. 2008. Mycodiversity studies in selected ecosystems of Greece: IV. Macrofungi from Abies cephalonica forests and other intermixed tree species (Oxya Mt., central Greece) 1 2 1 D.M. DIMOU *, G.I. ZERVAKIS & E. POLEMIS * [email protected] 1Agricultural University of Athens, Lab. of General & Agricultural Microbiology, Iera Odos 75, GR-11855 Athens, Greece 2 [email protected] National Agricultural Research Foundation, Institute of Environmental Biotechnology, Lakonikis 87, GR-24100 Kalamata, Greece Abstract — In the course of a nine-year inventory in Mt. Oxya (central Greece) fir forests, a total of 358 taxa of macromycetes, belonging in 149 genera, have been recorded. Ninety eight taxa constitute new records, and five of them are first reports for the respective genera (Athelopsis, Crustoderma, Lentaria, Protodontia, Urnula). One hundred and one records for habitat/host/substrate are new for Greece, while some of these associations are reported for the first time in literature. Key words — biodiversity, macromycetes, fir, Mediterranean region, mushrooms Introduction The mycobiota of Greece was until recently poorly investigated since very few mycologists were active in the fields of fungal biodiversity, taxonomy and systematic. Until the end of ’90s, less than 1.000 species of macromycetes occurring in Greece had been reported by Greek and foreign researchers. Practically no collaboration existed between the scientific community and the rather few amateurs, who were active in this domain, and thus useful information that could be accumulated remained unexploited. Until then, published data were fragmentary in spatial, temporal and ecological terms. The authors introduced a different concept in their methodology, which was based on a long-term investigation of selected ecosystems and monitoring-inventorying of macrofungi throughout the year and for a period of usually 5-8 years. -

Newsletter of Jun

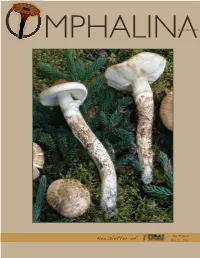

V OMPHALINISSN 1925-1858 Vol. V, No 6 Newsletter of Jun. 21, 2014 OMPHALINA OMPHALINA, newsletter of Foray Newfoundland & Labrador, has no fi xed schedule of publication, and no promise to appear again. Its primary purpose is to serve as a conduit of information to registrants of the upcoming foray and secondarily as a communications tool with members. Issues of OMPHALINA are archived in: is an amateur, volunteer-run, community, Library and Archives Canada’s Electronic Collection <http://epe. not-for-profi t organization with a mission to lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/omphalina/index.html>, and organize enjoyable and informative amateur Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Queen Elizabeth II Library mushroom forays in Newfoundland and (printed copy also archived) <http://collections.mun.ca/cdm4/ description.php?phpReturn=typeListing.php&id=162>. Labrador and disseminate the knowledge gained. The content is neither discussed nor approved by the Board of Directors. Therefore, opinions expressed do not represent the views of the Board, Webpage: www.nlmushrooms.ca the Corporation, the partners, the sponsors, or the members. Opinions are solely those of the authors and uncredited opinions solely those of the Editor. ADDRESS Foray Newfoundland & Labrador Please address comments, complaints, contributions to the self-appointed Editor, Andrus Voitk: 21 Pond Rd. Rocky Harbour NL seened AT gmail DOT com, A0K 4N0 CANADA … who eagerly invites contributions to OMPHALINA, dealing with any aspect even remotely related to mushrooms. E-mail: info AT nlmushrooms DOT ca Authors are guaranteed instant fame—fortune to follow. Authors retain copyright to all published material, and BOARD OF DIRECTORS CONSULTANTS submission indicates permission to publish, subject to the usual editorial decisions. -

Spore Prints of Boletus and Suit/Us

_;BULLETIN OF THE PUGET SOUND MYCOLOGICAL SOCIETY Number 349 February 1999 ON THE SIGNIFICANCE AND PROBLEMS OF SPORE scribing pale-spored variants of otherwise brown-spored species COLOR Brandon Matheny of Inocybe and Tubaria. Presumably, in these variants the path ways leading to spore pigment, carpophore (fruit-body) color, and Reliance on spore color alone---or any other single characteris spore wall thickness (in Inocybe) are blocked. However, one spe tic-is no guarantee ofreliable mushroom identification, For ac cies, I. rufolutea Favre, was described that had colorless spores curate identification, a combination of characteristics must be but a dark red-brown cap and pale yellow stem. Obviously, its employed, and this is what makes identification of many things a fruit body did not undergo the presumed blockage of pigment. challenge. Since the advent of recent systematic·methods that in Unlike fruit flies, where Fl and F2 generations can be bred to test clude more emphasis on anatomical detail, pale-spored groups the occurrence and frequency of certain traits, lnocybe does not and genera of mushrooms can now be found in traditionally dark lend itself to such genetic experimentation at this time. Thus con spored families .like the Crepidotaceae, Cortinariaceae, Paxil clusions regarding the autonomy of pale-spored variants remain laceae, and boletes. speculative. But I. rufolutea (and this collection should be re Crepidotus epibryus sensu Senn-Irlet, for exampfe: a furigus un examined) suggests that albinism may not be an accurate inter common at PSMS mushroom forays but occurring in wet depres pretation of the reason for its pale-spored condition. -

Sp. Nov. from Northeast China

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2013. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/124.269 Volume 124, pp. 269–278 April–June 2013 Russula changbaiensis sp. nov. from northeast China Guo-Jie Li1,2, Dong Zhao1, Sai-Fei Li1, Huai-Jun Yang3, Hua-An Wen1a*& Xing-Zhong Liu1b* 1State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No 3 1st Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Shanxi Institute of Medicine and Life Science, No 61 Pingyang Road, Xiaodian District, Taiyuan 030006, China Correspondence to *: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract —Russula changbaiensis (subg. Tenellula sect. Rhodellinae) from the Changbai Mountains, northeast China, is described as a new species. It is characterized by the red tinged pileus, slightly yellowing context, small basidia, short pleurocystidia, septate dermatocystidia with crystal contents, and a coniferous habitat. The phylogenetic trees based on ITS1-5.8S- ITS2 rDNA sequences fully support the establishment of the new species. Key words —Russulales, Russulaceae, taxonomy, morphology, Basidiomycota Introduction The worldwide genus ofRussula Pers. (Russulaceae, Russulales) is characterized by colorful fragile pileus, amyloid warty spores, abundant sphaerocysts in a heteromerous trama, and absence of latex (Romagnesi 1967, 1985; Singer 1986; Sarnari 1998, 2005). As a group of ectomycorrhizal fungi, it includes a large number of edible and medicinal species (Li et al. 2010). The genus has been extensively investigated with a long, rich and intensive taxonomic history in Europe (Miller & Buyck 2002). Although Russula species have been consumed in China as edible and medicinal use for a long time, their taxonomy has been overlooked (Li & Wen 2009, Li 2013).