World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azerbaijan 2015 International Religious Freedom Report

AZERBAIJAN 2015 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution protects the right of individuals to express their religious beliefs. Several laws and policies limit the free exercise of religion, especially for members of religious groups the government considered “nontraditional.” Authorities restricted the fundamental freedoms of assembly and expression and narrowed the operating space for civil society, including religious groups. The government detained several religious activists. Although reliable figures were unavailable, some local observers estimated the number of religious activists they considered to be political prisoners totaled 46, compared to 52 in 2014. Authorities raided gatherings of minority religious groups, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, Salafis, readers of texts by Islamic theologian Said Nursi, and suspected followers of the Islamic cleric and theologian Fethullah Gulen. Some religious organizations experienced difficulty registering with the government, and unregistered communities could not openly meet. The government imposed limits on the import, distribution, and sale of religious materials. The government sponsored workshops and seminars to promote religious tolerance, hosting the international Inter-Religious Dialogue on Religious Tolerance series, and supporting activities by the Jewish community. There were no reports of significant societal actions affecting religious freedom. U.S. embassy and visiting Department of State officials discussed religious freedom issues, including the government’s arrests of Jehovah’s Witnesses and treatment of minority religious groups, with government representatives. The embassy urged the government to address registration difficulties of religious groups and obstacles to the importation of religious literature and met with leaders of religious groups and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to discuss specific concerns related to religious freedom. -

Armenian Crimes

ARMENIAN CRIMES KHOJALY GENOCIDE Over the night of 25-26 February 1992, following massive artillery bombardment, the Armenian armed forces and paramilitary units, with the support of the former USSR’s 366th Motorized Infantry Regiment attacked an Azerbaijani town of Khojaly. Around 2,500 remaining inhabitants attempted to flee the town in order to reach Aghdam, the nearest city under Azerbaijani control. However, their hope was in vain. The Armenian forces and paramilitary units ambushed and slaughtered the fleeing civilians near the villages of Nakhchivanly and Pirjamal. Other civilians, including women and children were either captured by the Armenian soldiers or froze to death in the snowy forest. Only a few were able to reach Aghdam. 1 During the assault both former presidents of Armenia, Serzh Sargsyan and Robert Kocharian, as well as other high-ranking officials (Zori Balayan, Vitaly Balasanyan and etc) of Armenia, participated personally in the Khojaly Genocide. Speaking to foreign journalists, Armenia’s leaders have admitted their participation and shown no remorse. 2 THE VICTIMS OF THE KHOJALY GENOCIDE • 613 people killed, including 63 children; 106 women; 70 elderly; • 8 families completely annihilated; • 25 children lost both parents; • 130 children lost one parent; • 487 wounded; • 1275 taken hostage; • 150 still missing. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KHOJALY GENOCIDE IN INTERNATIONAL MEDIA The Khojaly tragedy was widely covered in the international media despite the information blockade and the large-scale Armenian propaganda effort. The world community could not close eyes to the gravity of this crime against humanity and cruelty of perpetrators. 12 13 14 15 16 17 THE JUSTICE FOR KHOJALY CAMPAIGN The Justice for Khojaly International Awareness Campaign was initiated in 2008 by Leyla Aliyeva, the Vice President of the Heydar Aliyev Foundation. -

Az-Fact-Finding Mission Report of The

The Commissioner for Human Rights (Ombudsman) of the Republic of Azerbaijan REPORT concerning the factual evidences of extensive civilian casualties and damage to civilian objects in Barda city caused by the ballistic missiles launched by Armenian armed forces Baku -2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................................................3 1. Overview of Barda city shelled by Armenia ....................................................4 2. Activity of the Ombudsman related to the investigation of Barda attacks by Armenian military...................................................................................................................5 2.1. Call of the Ombudsman on International Community about Military Aggression of Armenia ………………………………………………………………………………5 2.2. Fact-Finding Mission of the Ombudsman on Military Aggression by Armenia .................................................................................................................................................5 3. Photo-facts of human loss and destructions in Barda caused by military of Armenia...................................................................................................................................9 4. War crimes and terror acts committed by Armenia against civilians of Azerbaijan with the use of prohibited munitions in the context of international legal responsibility .......................................................................................................................16 -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council E/CN.4/1999/79/Add.1 25 January 1999 Original: ENGLISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Fifty•fifth session Item 14 (c) of the provisional agenda SPECIFIC GROUPS AND INDIVIDUALS: MASS EXODUSES AND DISPLACED PERSONS Report of the Representative of the Secretary•General, Mr. Francis M. Deng, submitted pursuant to Commission on Human Rights resolution 1998/50 Addendum Profiles in displacement: Azerbaijan CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ....................... 1 • 13 2 I. THE DISPLACEMENT CRISIS .............. 14 • 39 5 A. The country context .............. 14 • 19 5 B. Conflict as the cause of displacement ..... 20 • 28 7 C. Patterns of displacement ........... 29 • 39 10 II. RESPONSIBILITIES AND THE LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS FOR RESPONSE ....... 40 • 57 13 A. The Government ................ 40 • 51 13 B. The international community .......... 52 • 57 16 III. CURRENT CONDITIONS OF THE DISPLACED ........ 58 • 97 18 IV. TOWARDS DURABLE SOLUTIONS ............. 98 • 113 30 A. Supporting present possibilities for return .. 100 • 108 31 B. Promoting preparedness for return or resettlement and reintegration ........ 109 • 113 33 V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .......... 114 • 120 35 GE.99•10356 (E) E/CN.4/1999/79/Add.1 page 2 Introduction 1. Azerbaijan has one of the largest displaced populations in the world: approximately one out of every eight persons in the country is an internally displaced person or a refugee. Most of the displacement is caused by the conflict over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. By the time a ceasefire was concluded in May 1994, an estimated 650,000 Azeris had become internally displaced by the conflict, adding to the existing displaced population of 185,000 ethnic Azeri refugees who had come from Armenia between 1988 and 1990 and, unrelated to the conflict, over 40,000 Meskhetian Turks who had come from Uzbekistan in 1989. -

Human Rights Impact Assessment of the State Response to Covid-19 in Azerbaijan

HUMAN RIGHTS IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE STATE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 IN AZERBAIJAN July 2020 Cover photo: Gill M L/ CC BY-SA 2.0/ https://flic.kr/p/oSZ9BF IPHR - International Partnership for Human Rights (Belgium) W IPHRonline.org @IPHR E [email protected] @IPHRonline BHRC - Baku Human Rights Club W https://www.humanrightsclub.net/ Bakı İnsan Hüquqları Klubu/Baku Human Rights Club Table of Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 5 BRIEF COUNTRY INFORMATION 5 Methodology 6 COVID 19 in Azerbaijan and the State’s response 7 NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE PANDEMIC AND RESTRICTIVE MEASURES 7 ‘SPECIAL QUARANTINE REGIME’ 8 ‘TIGHTENED QUARANTINE REGIME’ 9 ADMINISTRATIVE AND CRIMINAL LIABILITY FOR FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH QUARANTINE RULES 10 Impact on human rights 11 IMPACT ON A RIGHT TO LIBERTY 12 IMPACT ON PROHIBITION OF ILL-TREATMENT: DISPROPORTIONATE POLICE VIOLENCE AGAINST ORDINARY CITIZENS 14 IMPACT ON FAIR TRIAL GUARANTEES 15 IMPACT ON A RIGHT TO PRIVACY 15 IMPACT ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND A RIGHT TO IMPART INFORMATION 16 IMPACT ON FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY 18 IMPACT ON HEALTH CARE AND HEALTH WORKERS 19 IMPACT ON PROPERTY AND HOUSING 20 IMPACT ON SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RIGHTS 20 IMPACT ON A RIGHT TO EDUCATION 21 IMPACT ON MOST VULNERABLE GROUPS 21 Recommendations to the government of Azerbaijan 25 Executive summary As the world has been struct by the COVID-19 outbreak, posing serious threat to public health, states resort to various extensive unprecedented measures, which beg for their assessment through the human rights perspective. This report, prepared by the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) and Baku Human Rights Club (BHRC), examines the measures taken by Azerbaijan and the impact that it has on human rights of the Azerbaijani population, including those most vulnerable during the pandemic. -

1287Th PLENARY MEETING of the COUNCIL

PC.JOUR/1287 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe 29 October 2020 Permanent Council Original: ENGLISH Chairmanship: Albania 1287th PLENARY MEETING OF THE COUNCIL 1. Date: Thursday, 29 October 2020 (in the Neuer Saal and via video teleconference) Opened: 10.05 a.m. Suspended: 12.55 p.m. Resumed: 3 p.m. Closed: 5.55 p.m. 2. Chairperson: Ambassador I. Hasani Ms. E. Dobrushi Prior to taking up the agenda, the Chairperson reminded the Permanent Council of the technical modalities for the conduct of meetings of the Council during the COVID-19 pandemic. 3. Subjects discussed – Statements – Decisions/documents adopted: Agenda item 1: REPORT BY THE DIRECTOR OF THE CONFLICT PREVENTION CENTRE Chairperson, Director of the Conflict Prevention Centre (SEC.GAL/157/20 OSCE+), Russian Federation (PC.DEL/1458/20 OSCE+), Germany-European Union (with the candidate countries Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia; the European Free Trade Association countries Iceland and Liechtenstein, members of the European Economic Area; as well as Andorra, Georgia, Moldova and San Marino, in alignment) (PC.DEL/1517/20), Armenia (Annex 1), Turkey (PC.DEL/1488/20 OSCE+), United States of America (PC.DEL/1457/20), Azerbaijan (Annex 2), Belarus (PC.DEL/1460/20 OSCE+), Switzerland (PC.DEL/1461/20 OSCE+), Georgia (PC.DEL/1467/20 OSCE+), Norway (PC.DEL/1473/20), United Kingdom, Kazakhstan PCOEW1287 - 2 - PC.JOUR/1287 29 October 2020 Agenda item 2: REVIEW OF CURRENT ISSUES Chairperson (a) Russia’s ongoing aggression against Ukraine and illegal occupation of Crimea: -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

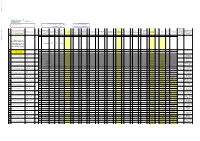

PIU Director: Sabir Ahmadov TTL: Robert Wrobel Credit : USD 66.7 Mln Proc

Public Disclosure Authorized C Additional Financing for IDP Revision Date: 20 Living Standards and August 2018 Livelihoods Project PIU Director: Sabir Ahmadov TTL: Robert Wrobel Credit : USD 66.7 mln Proc. Specialist: Emma Mammadkhanova Operations Officer: Nijat Veliyev PAS: Sandro Nozadze Program Assistant: Vusala Asadova Public Disclosure Authorized Contracts,Am Reception Short endments IDP Living Standards and Estimated Cost Contr. Prior / No Objection Company name Note Selection of Listing/RFP Invitation for Proposal Technical Final Contract (Amount, Actual Livelihoods Project Name Procurement Ref. # / Actual (USD) Type LS Post Ad of EOI No Objection No Objection to Sign Start Completion which is awarded # Method Expression submssion RFP Submission Evaluation Evaluation Signature Days Date and of Assignment / Contract Type- incl VAT / TB Review Contract a contract Category of Interest to the Bank Execution reason should Plan Plan / Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval be indicated Hiring the services of Public Disclosure Authorized individual consultants for A about 300 contracts for IC-1 250,000.00 IC TB Post technical supervision over contracts implementation p A- Micro-projects A P 352.49 IC Post 2/9/2017 2/9/2017 60 4/10/2017 Mammadov Local Technical Supervisor SFDI/8627-AZ/080 352.49 Public Disclosure Authorized A 352.49 IC Post 2/9/2017 2/9/2017 60 4/10/2017 Farzali Vali P 352.49 IC Post 2/9/2017 2/9/2017 60 4/10/2017 -

Karabakh's Cult Architecture

Karabakh Vilayat KaRIMOV Doctor of Architecture Karabakh’s cult architecture The Ganjasar monastery (Agdara District) THE arcHITECTURAL HERITagE OF AZErbaiJAN, INCLUDING KarabakH, Has BECOME ONE OF THE MEMORY FORMS OF ITS AUTOCHTHONS. THANKS TO THIS THE COUNTRY’S arcHITECTURE PERMANENTLY EXPANDS THE VALUES SOCIETY POssEssES as A SOCIAL OrgaNISM. MONUMENTS OF AZErbaiJAN’S MATERIAL CULTURE ARE AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE facT THAT GREAT arcHITECTURAL masTERPIECES ARE NOT SO MUCH THE RESULT OF INDIVIDUAL WORK as THEY ARE A PRODUCT OF THE ENTIRE SOCIETY, THE RESULT OF CREATIVE EFFORTS OF A WHOLE PEOPLE. he Karabakh architecture de- The exceptionally favorable work in ancient cities. Various natu- serves special mention. While natural and geographic conditions ral rocks and clay led to the devel- Treviewing the development of of Karabakh preconditioned the opment and spread of a number of architecture in this historical region development of farming and cattle construction methods and architec- of Azerbaijan, we should point to breeding. Numerous settlements tural forms, which played a major the fact that it covered a large area. were established here which even- role in the subsequent develop- Karabakh’s ancient land was a tually transformed into large and ment of construction art. center of civilization not only for well-fortified cities linked to many Karabakh’s architectural monu- Azerbaijan, but also for the entire countries of the East and West by ments, partially preserved or lying Caucasus and beyond. The archi- caravan roads. The natural wealth in ruins, represent invaluable factual tecture of a significant artistic of the Karabakh land and the abun- evidence of people’s rock chroni- and historical value evolved here dance of construction materials cles. -

Eastern Partnership Enhancing Judicial Reform in the Eastern Partnership Countries

Eastern Partnership Enhancing Judicial Reform in the Eastern Partnership Countries Efficient Judicial Systems Report 2014 Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law Strasbourg, December 2014 1 The Efficient Judicial Systems 2014 report has been prepared by: Mr Adiz Hodzic, Member of the Working Group on Evaluation of Judicial systems of the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) Mr Frans van der Doelen, Programme Manager of the Department of the Justice System, Ministry of Security and Justice, The Netherlands, Member of the Working Group on Evaluation of Judicial systems of the CEPEJ Mr Georg Stawa, Head of the Department for Projects, Strategy and Innovation, Federal Ministry of Justice, Austria, Chair of the CEPEJ 2 Table of content Conclusions and recommendations 3 Part I: Comparing Judicial Systems: Performance, Budget and Management Chapter 1: Introduction 11 Chapter 2: Disposition time and quality 17 Chapter 3: Public budget 26 Chapter 4: Management 35 Chapter 5: Efficiency: comparing resources, workload and performance (28 indicators) 44 Armenia 46 Azerbaijan 49 Georgia 51 Republic of Moldova 55 Ukraine 58 Chapter 6: Effectiveness: scoring on international indexes on the rule of law 64 Part II: Comparing Courts: Caseflow, Productivity and Efficiency 68 Armenia 74 Azerbaijan 90 Georgia 119 Republic of Moldova 139 Ukraine 158 Part III: Policy Making Capacities 178 Annexes 185 3 Conclusions and recommendations 1. Introduction This report focuses on efficiency of courts and the judicial systems of Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, commonly referred the Easter Partnership Countries (EPCs) after the Eastern Partnership Programme of the European Union. -

COJEP Int. Report Azerbaidjan Armenia 2020

New military clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan REPORT On the civilian casualties and destructions caused by attacks of Armenia on densely populated areas of Azerbaijan between 27 September – 28 October 2020 28 October 2020 October 2020 COJEP INTERNATIONAL INTRODUCTION Background The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict is one of the longest-standing protracted conflicts in the region, which has been going on for nearly 3 decades. As a result of this, the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan and 7 adjacent districts of Azerbaijan, namely Lachin, Kalbajar, Aghdam, Fuzuli, Jabrayil, Gubadli and Zangilan, were occupied by Armenia. The conflict affected the lives of over a million of Azerbaijanis who lived in the Nagorno-Karabakh region and 7 adjacent districts of Azerbaijan, causing a number of social, economic and humanitarian problems. The above-mentioned 7 districts are not a part of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The total area of Nagorno-Karabakh region is 4400 km2, while the total area of 7 districts is almost 3 times larger (11.000 km2). More than 90% of the total number of IDPs (which is more than 1 million) represent those 7 districts. It should also be mentioned that the number of Azerbaijani people forced to leave the Nagorno-Karabakh region is now 86 thousand people. It is the attention capturing fact, that the number of IDPs only from Aghdam (191.700 people) is larger than of the Nagorno-Karabakh region (the overall number of Armenians, Azerbaijanis and other nationalities populating this territory before the conflict was 189.085 people). So, the population of 7 districts is almost 5 times more than of Nagorno- Karabakh itself. -

1. Admission of Students to Higher Education Institutions

SCIENTIFIC STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF THE RESULTS OF STUDENTS ADMISSION TO THE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2010/2011 M.M.Abbaszade, T.A.Badalov, O.Y.Shelaginov 1. ADMISSION OF STUDENTS TO HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS Admission of students to higher education institutions of the Republic of Azerbaijan for the academic year of 2010 – 2011 was held by the State Students Admission Commission (SSAC) in full conformity with the “Admission Rules to higher education institutions and to specialized secondary education institutions on the basis of complete secondary education of the Republic of Azerbaijan”. According to admission rules, admission to all civil higher schools, special purpose education institutions of Ministry of Defenсe, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of National Security, Ministry of Emergency Situations, and State Border Service has been held in a centralized way. At first sight, although there are annually repeated procedures and regulations, activities of SSAC are improved year by year, in general. Innovations, first of all, derive from the necessity of taking into consideration the development demand of education system and qualified provision of the youth’s interests to education. Therefore, proposals from the public to SSAC are analyzed, demands of graduates are studied, summarized, and changes are made in necessary cases. The innovations are intended to provide the integration of logistics, content and technology of admission examinations into the international standards. The following innovations were applied in the process of admission examinations to higher and specialized secondary education institutions for the academic year of 2010 – 2011: 1. After adoption of law of the Republic of Azerbaijan “On education”, this year for the first time winners of international competitions and contests have been admitted to corresponding specialities out of competition.