Henry Kaiser, Troy Ruttman, and Madman Muntz Three Originals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sidelight, February 2020

THE SIDELIGHT Published by KYSWAP, Inc., subsidiary of KYANA Charities 3821 Hunsinger Lane Louisville, KY 40220 February 2020 Printed by: USA PRINTING & PROMOTIONS, 4109 BARDSTOWN ROAD, Ste 101, Louisivlle, KY 40218 KYANA REGION AACA OFFICERS President: Fred Trusty……………………. (502) 292-7008 Vice President: Chester Robertson… (502) 935-6879 Sidelight Email for Articles: Secretary: Mark Kubancik………………. (502) 797-8555 Sandra Joseph Treasurer: Pat Palmer-Ball …………….. (502) 693-3106 [email protected] (502) 558-9431 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Alex Wilkins …………………………………… (615) 430-8027 KYSWAP Swap Meet Business, etc. Roger Stephan………………………………… (502) 640-0115 (502) 619-2916 (502) 619-2917 Brian Hill ………………………………………… (502) 327-9243 [email protected] Brian Koressel ………………………………… (502) 408-9181 KYANA Website CALLING COMMITTEE KYANARegionAACA.com Patsy Basham …………………………………. (502) 593-4009 SICK & VISITATION Patsy Basham …………………………………. (502) 593-4009 THE SIDELIGHT MEMBERSHIP CHAIRMAN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF KYSWAP, Roger Stephan………………………………… (502) 640-0115 INC. LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY HISTORIAN Marilyn Ray …………………………………… (502) 361-7434 Deadline for articles is the 18th of preceding month in order to have it PARADE CHAIRMAN printed in the following issue. Articles Howard Hardin …………………………….. (502) 425-0299 from the membership are welcome and will be printed as space permits. CLUB HOUSE RENTALS Members may advertise at no charge, Ruth Hill ………………………………………… (502) 640-8510 either for items for sale or requests to obtain. WEB MASTER Editorials and/or letters to the editor Interon Design …………………………………(502) 593-7407 are the personal opinion of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the CHAPLAIN official policy of the club. Ray Hayes ………………………………………… (502) 533-7330 LIBRARIAN Jane Burke …………………………………….. (502) 500-8012 From the President Fred Trusty Last month I reported that we lost 17 members in 2019 for various reasons. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\My Documents\Flyers-Kaiser\FLYER-5

“Kaiser Flyer # 5” Joseph W. (Jeeps) Frazer Joseph W. Frazer was the automobile “expert” part of the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation. He was respected by the Detroit “in” crowd and was well-known as an outstanding automotive expert and salesman. He was born in Nashville, Tenn in 1892 into a well-to-do family. His brother operated a Packard Agency in Nashville and young Joe would doodle with drawing pictures of cars during his school days. He could have started his working career at various high- salary jobs in an executive position in other industries but chose instead to begin work at Packard as a mechanic’s helper at less than 20 cents per hour. He wanted to be close to his love - Joseph W. Frazer in his Willow Run Office early 1946 automobiles. Although he was very successful in several aspects of the automobile business, including starting the first technical school for automotive mechanics, his heart was always in sales and promotion. He sold Packard motor cars in New York and at his brother’s Nashville dealership and by the end of World War I he was ready to begin his quest for making his mark on the automobile industry. He first took an opportunity at GM’s Chevrolet Division in sales. He was soon promoted into the GM Export Division as Treasurer and helped to organize the General Motors Acceptance Division, one of the first strictly automobile credit agencies established in the country. GM later loaned Joe to Pierce-Arrow to assist them in creating their own credit agency. -

Story, Page 2 ' ·

t Volume 6-Number 3 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY l, 1946 4 Pages Story, Page 2 ' · Here is. a front cl~se-up. of the c r of The Future new Kaiser car which will com- pete in the low-priced field. The simple yet beautiful front grill work keeps harmony with the flowing body lines. Crowds in New York jammed traffic to place orders for the front-wheel-drive car. Production Giant Here i_s an air view of the ~100,000,000 Willow Ru~, Mich., plant of Kaiser-Frazer corporation where new automobiles are to be produced. Willow Run is the largest building in the world under a single roof. There are parking facilities for 20,000 cars, multi-lane super-highways and railroad spurs for shipping. - Traffic Jammed As New Yorkers View l{aiser Car On Sunday, January 20, approximately 50,000 New York ers blocked traffic over a four-block area, lined up four abreast in long lines despite frigid weather, necessitated calling out some 70 extra policemen and firemen to clear the blocked streets, and, according to New York newspapers, over-ran the foyer, three flights of stairs, and the vicinity of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. They had come to the first public showing of the new Kaiser KAISER-FRAZER and Frazer automobiles. In the first four hours 25,000 persons inspected the cars on display at the hotel. PLANT HAS TOP They placed 1000 orders. By the time the show ended in the mictdle of the week, 156,500 per LABOR FACILITIES sons had seen the new cars and ap- The giant $100.000,000 Willow • This cut-away drawing shows "packaged power" front wheel di;ive proximately 10,000 had placed or- Run plant, where the Kaiser-Frazer Ph an t Om VleW and new "torsionetic" suspension of the new Kaiser car. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\My Documents\Flyers-Kaiser\Flyer-1.Wpd

“Kaiser Flyer # 1” The 1952 thru 1955 Kaiser “V” Emblem How About The “V” Emblem In 1948 the Kaiser Engineers begin development of an Overhead Valve V-8 Engine. Its original displacement was 288 cubic inches. The original Aluminum block castings (as Henry Kaiser had dictated) were changed to iron blocks in the last phase. The initial test engines experienced crankshaft failures until the balance problem was cured. It is interesting to note that the initial Chevrolet V-8 “Small-Block” prototype engines experienced crankshaft cracking at exactly the same place. The final Kaiser V8 design was a very good reliable engine and had many innovations for its time. The 1949 Kaiser designed V8 was of modern overhead valve design and used a new “green-sand” casting method. General Motors later also adopted this method of casting for the now-famous "Chev Small-Block V8" introduced in 1955. My father was one of the few Kaiser Dealers who actually witnessed the Kaiser engine running on a test stand at the Kaiser plant. The new Kaiser OHV engine was initially scheduled for production for the 1951 Kaiser models. However, Henry J. Kaiser had a passion to build an American “Peoples Car” to be to Americans what the Volkswagen was to the Germans. He had harbored this dream since before World War II had began. Kaiser had publicly announced his intent to build a “Peoples Car” to sell for $400 in 1942 and had actually experimented with a small fiberglass-bodied economy car as early as 1944. Over fifty prototypes were actually built. -

November 2019 Master

THE MOTO METER CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA REGION, ANTIQUE AUTOMOBILE CLUB OF AMERICA WEBSITE: CEDARRAPIDSREGIONAACA.COM FACEBOOK: CEDAR RAPIDS ANTIQUE CAR CLUB LOVED BY SOME, CUSSED BY OTHERS, READ BY EVERYBODY November 2019 2019 Regional Board Members President: Jane Hawley 319-360-5599 [email protected] Vice President: The month of October held the year’s biggest event for our club. On October Larry Yoder 319-350-4339 19th, we will hold the annual Cedar Rapids AACA Swap Meet at Hawkeye Secretary: Downs. The treasurer will soon be paying bills and counting money and will Jeri Stout 319-622-3629 have the numbers to report soon. Overall, I anticipate a successful swap meet Alt: Sylvia Copler 319-377-3772 with perfect weather. A week later, we will celebrate our successful swap Treasurer: meet at Pizza Ranch for all of those members who helped with the event. Lee Sharon Schminke 319-472-4372 Votrabek did a great job as chairman as usual and he had a wonderful Flowers Joann Kiefer 319-210-5921 committee that helped him take on some of the work. Next year we may see a big change. Hawkeye Downs has been sold and our Directors: swap meet may need to find a new home. We are considering moving it to the Carl Ohrt 319-365-1895 Lee Votroubek 319-848-4634 Central City Fairgrounds, just north of Marion on Highway 13. If this Rich Mishler 319-364-8863 happens, how will we deal with this change of venue? We will be proactive in Dan Ortz 319-366-3142 Judy Ortz 319-360-1832 our approach and inform vendors as early as possible of the change. -

NOVEMBER BOOK.Indb

Complete Monterey Coverage 209 Cars Rated SportsKeith Martin’s Car Market The Insider’s Guide to Collecting, Investing, Values, and Trends Scruffy Talbot Miles Collier on history, patina, and $4.8m of charm ►► Ferrari,Ferrari, aa marketmarket inin transitiontransition ►► Gooding’sGooding’s BugattiBugatti bonanzabonanza ►► PhilPhil HillHill 1927–20081927–2008 November 2008 www.sportscarmarket.com SportsKeith Martin’s Car Market The Insider’s Guide to Collecting, Investing, Values, and Trends November 2008 . Volume 20 . Number 11 50 McQueen’s Porsche 52 Tucker—A million-dollar car 46 Talbot-Lago—preservation is the key IN-DEPTH PROFILES GLOBAL AUCTION COVERAGE What You Need To Know 209 Cars Examined and Rated at Five Sales FERRARI BONHAMS & BUTTERFIELDS 38 1973 Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Spyder—$1.5m 68 Carmel Valley, CA: B&B pulls out all the stops with a $21m result A damn fine Daytona cruises to top Spyder at Quail Lodge. price of the weekend. Donald Osborne Steve Ahlgrim RM AUCTIONS ENGLISH 86 Monterey, CA: 19 Ferraris lead the way to a $44m weekend at 42 1936 Lagonda LG45R Rapide—$1.4m the Portola Plaza. Care and feeding of a septuagenarian. Carl Bomstead Paul Hardiman RUSSO AND STEELE ETCETERINI 102 Monterey, CA: Drew and company top $9.1m with the usual 46 1939 Talbot-Lago T150C SS Aerocoupe—$4.8m mix of sports and muscle. Pourtout’s elegant racer, a story in every dent. Raymond Nierlich Miles Collier GOODING & COMPANY 48 1966 Bizzarrini Strada 5300 GT Coupe—$572k 114 Pebble Beach, CA: $7.9m Bugatti Type 57SC sets a record on the way to a record-setting $64.8m sale. -

NSN October 2018 B.Pub

Volume 18 Issue 10 October 1, 2018 My Pride and Joy Steve Allen’s Beautiful Barn Find This month we are reprinting a story from the September 2018 issue of the Road Race Lincoln Registry magazine, VIVA CARRERA, courtesy of Mike Denny, publisher. It is an interesting saga about one person’s passion for a very particular automobile, a 1953 Lincoln Capri. Here is the story as presented by the owner of this fine Lincoln — Steve Allen. Anyone with a passion for history and antique automobiles, inevitably finds them- selves daydreaming of their idea of the perfect barn find. The reality is that it rarely Welcome to the plays out as you envision. However, there are those exceptions that come along when you least expect it. Take my 1953 Lincoln Capri Convertible, for example. Northstar News, the My wife (Marie) and I had been discussing the long list of possibilities for what was monthly publication of to be the second car in our small collection. The problem was that we had such a wide the Northstar Region range of likes, we found it difficult to zero in on any one choice. of the Lincoln and One evening we were watching an old Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz movie called the Continental Owners “Long Long Trailer.” It was a comedy of a newly married couple; who pulled an over- sized trailer across the country and it nearly broke up their marriage. The car that was Club. We value your used in the film was an early 1950s convertible. “That’s it!” Marie said, “That’s the kind opinions and appreciate of car I’d like own. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\My Documents\Flyers-Kaiser\FLYER-6

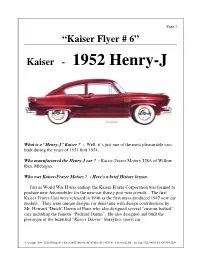

Page 1 “Kaiser Flyer # 6” Kaiser - 1952 Henry-J What is a “Henry-J” Kaiser ? - Well, it’s just one of the most pleasurable cars built during the years of 1951 thru 1954. Who manufactured the Henry-J car ? - Kaiser-Frazer Motors, USA of Willow Run, Michigan. Who was Kaiser-Frazer Motors ? - Here’s a brief History lesson. Just as World War II was ending, the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation was formed to produce new Automobiles for the new-car thirsty post-war crowds. The first Kaiser-Frazer Cars were released in 1946 as the first mass-produced 1947 new car models. They were unique designs for their time with design contributions by Mr. Howard "Dutch" Darrin of Paris who also designed several “custom-bodied” cars including the famous “Packard Darrin”. He also designed and built the prototype of the beautiful “Kaiser Darrin” fiberglass sports car. Copyright 1998 - 2006 William P. (“Kaiser Bill”) Brown HC 65 Box 49, 18530 W. Yellowstone Rd., Altonah, Utah 84002 Tel 435-454-3098 Page 2 Although Darrin had created an entirely new modern design for the 1947 Kaiser-Frazer cars, he felt that the Kaiser-Frazer engineers had ruined his design with major production compromises to rush the new 1947 models into production, and he was furious. Darrin's design was low-slung and sleek, and although Darrin's basic body lines were somewhat adapted and the first Kaisers and Frazers were quite good-looking, they were much more fat and bulbous than the original Darrin design. During the years 1947 through 1954, Howard Darrin continued to contribute his design talents to Kaiser (Frazer had bowed out of the company in 1951). -

1952 Muntz Jet (Her Nickname Is “BUTTERCUP”)

1952 Muntz Jet (Her nickname is “BUTTERCUP”) M-130 This Muntz Jet is the 30th of 198 cars built car equipped with an ice chest and by The Muntz Car Company during the liquor cabinet in the rear arm seats. The period 1951 thru 1954. It is sometimes interior dashboard received an aircraft credited as the first high-performance like, Stewart-Warner instrumentation; personal luxury car built in America with as well as, what is considered Detroit’s the capability of doing 0 to 60 in 8.6 first modern console/bucket seat layout. seconds. Earl Muntz became the largest The Muntz was available in colors such Used Car Dealer in the world during as Boy Blue, Elephant Pink, Chartreuse, WWII, often paying servicemen $50 to Purple and Buttercup Yellow. Famous drive a car from the Midwest to California owners of the Muntz Jet include many where he reaped bigger margins. In Hollywood Celebrities such as: Clara 1949, he became a multi unit Kaiser Bow, Vic Damone, Grace Kelly and Dealer and was credited with selling Mickey Rooney. This M-130 Muntz Jet 22,000 out of 147,000 cars built that year. was initially purchased by the Pillsbury In 1950, he decided to build his own car, Family and later discovered in Michigan the Muntz Jet and purchased the Frank about 50 years ago. In 1952, a Muntz Kurtis Company and expanded this Jet sold for $5,500 while a 1952 Cadillac two seat creation into a four passenger Convertible sold for $3,800. Earl Muntz was a combination • Became a household name after WWII of PT Barnum’s hucksterism, when Bob Hope, Groucho Marx, Red a pinch of Thomas Edison’s Skelton, Jack Benny and others poked curiosity and President Trump’s early fun at his wacky sales pitches…thus the entrepreneurial adventures. -

Chryslerdealersremain.Pdf

DEALER CURE DEALER NAME MAJORITY OWNER DEALER ADDRESS CODE LINES AMOUNT ADAMS AUTOMOTIVE INC ROBERT J ADAMS JR DBA ADAMS JEEP 23248 J $0.00 1799 WEST STREET ANNAPOLIS, MD 21401-3295 ADAMS JEEP OF MARYLAND INC RONALD J ADAMS 3485 CHURCHVILLE ROAD 26145 J $0.00 ABERDEEN, MD 21001-1013 ADAMS MOTOR COMPANY ALLAN C ADAMS 702 W HIGHWAY 212 44084 DTCJ $0.00 MONTEVIDEO, MN 56265-1560 ADAMSON MOTORS INC PATRICK T ADAMSON 4800 HIGHWAY 52 NORTH 38999 CDTJ $0.00 ROCHESTER, MN 55901-0196 ADEL CHRYSLER INC JAMES W DOLL 818 COURT ST 65191 CDTJ $0.00 ADEL, IA 50003 ADIRONDACK AUTO SERV INC GEORGE C HUTTIG ROUTE 9 64053 CDTJ $0.00 ELIZABETHTOWN, NY 12932 ADVANCE AUTO SALES INC JOHN ISAACSON DBA LEE CHRYSLER JEEP DODGE 36100 CDTJ $0.00 777 CENTER ST AUBURN, ME 04210-3097 ADVANTAGE CHRYSLER DODGE ARTHUR SULLIVAN DBA ADVANTAGE CHRYSLER DODGE JEEP 44393 DTCJ $0.00 JEEP, INC 18311 US HWY 441 MT DORA, FL 32757 ADZAM AUTO SALES INC BARRY L SCHAEN 519 BEDFORD ROAD 23150 JCDT $0.00 BEDFORD HILLS, NY 10507-1696 AIRPORT CHRYSLER DODGE CHRISTOPHER F DBA AIRPORT CHRYSLER DODGE JEEP 60338 CDTJ $0.00 JEEP, LLC DOHERTY 5751 EAGLE VAIL DR ORLANDO, FL 32822-1529 AKIN FORD CORPORATION BRADLEY S AKINS DBA AKINS DODGE JEEP CHRYSLER 66709 CDTJ $0.00 220 WEST MAY STREET WINDER, GA 30680 AL DEEBY DODGE CLARKSTON, ALPHONSE J DEEBY III DBA AL DEEBY DODGE CLARKSTON, INC. 45196 DT $0.00 INC. 8700 DIXIE HIGHWAY CLARKSTON, MI 48348 AL SMITH CHRYSLER-DODGE, ALTON C SMITH DBA AL SMITH CHRYSLER-DODGE, INC. -

In the Supreme Court of Florida

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA CONSOLIDATED CASE NOS.: SC10-1068 & SC10-1070 CASE NO.: SC10-1070 MONICA STEELE, Petitioner, v. GEICO INDEMNITY COMPANY, Respondent. -AND- CASE NO.: SC10-1068 RETHELL BYRD CHANDLER, etc., et al., Petitioners, v. GEICO INDEMNITY COMPANY, Respondent. RESPONDENT GEICO’S CONSOLIDATED BRIEF ON THE MERITS ANGELA C. FLOWERS KUBICKI DRAPER Attorneys for Respondent GEICO 1805 SE 16th Avenue, Suite 901 Ocala, FL 34471 Tel: (352) 622-4222 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................... iii OTHER AUTHORITIES ........................................................................................... v STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS ........................................................... 1 APPLICABLE POLICY LANGUAGE .................................................................... 3 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 6 STANDARD OF REVIEW ....................................................................................... 7 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................. 8 I. THE FIRST DISTRICT’S DECISION CORRECTLY FOLLOWS THE RULE THAT THE WORD ‘PERMISSION’ AS USED IN AN AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE CONTRACT’S DEFINITION OF A “TEMPORARY SUBSTITUTE AUTO” REFERS TO THE ACTUAL PERMISSION GRANTED BY THE OWNER AND IS NOT COEXTENSIVE WITH THE EXPANDED DEFINITION OF PERMISSION USED IN APPLYING TORT LIABILITY -

C:\Users\Mark\Desktop\SL December\The Starliner1207 Edit

The Starliner December, 2007 Vol. 39, No. 6 Who is this Handsome Gent, and Whose Hawk is That? Mike Burke has Written the Story - see Cover Story, Inside. Visit us on the Internet at http://www.studebakerclubs.com /blackhawk The Black Hawk Chapter is the officially chartered representative of the Studebaker Drivers Club for the Northern Illinois area. The Studebaker Drivers Club is dedicated to the preservation of the Studebaker name and Studebaker related vehicles produced by the company during its period in the transportation field. A sincere interest in this cause is the only requirement for membership. Vehicle ownership is not a requirement. The Black Hawk Chapter fully supports the parent Studebaker Drivers Club, and requires membership therein. The SDC provides the membership with yearly national meetings, a monthly publication [Turning Wheels], technical assistance, historical data, assistance in parts and vehicle locating, and a membership roster on a national level. The Black Hawk Chapter provides the same services on a local level, in addition to monthly activities including 10 issues of the Starliner, dinner meetings, picnics, driving events, and fellowship and technical sessions. BLACK HAWK CHAPTER OFFICERS PRESIDENT VICE-PRESIDENT SECRETARY TREASURER ROLF SNOBECK ED MANLY RON SMITH MIKE BURKE nd 336 W. Harding Rd. 22 E.Stonegate Dr. 37 West 66 th St., Apt. #4 8751 S 52 Ave Lombard, IL 60148 Prospect Hts, IL 60070 Westmont, IL 60559 Oak Lawn, IL 60453 [630] 627-0134 847-215-9350 708-423-5892 630-241-2343 RSnobeck@ [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] anthonyroofing.com Membership / Publisher ACTIVITIES DIRECTOR Asst.