By Mohsen Makhmalbaf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Detailseite

W_5220:W_ 26.01.2008 16:22 Uhr Seite 58 Berlinale 2008 AVAZE GONJESHK-HA Wettbewerb THE SONG OF SPARROWS THE SONG OF SPARROWS THE SONG OF SPARROWS Regie: Majid Majidi Iran 2008 Darsteller Reza Naji Länge 96 Min. Maryam Akbari Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Kamran Dehghan Farbe Hamed Aghazi Shabnam Akhlaghi Stabliste Neshat Nazari Buch Majid Majidi Mehran Kashani Kamera Tooraj Mansouri Kameraassistenz Mohammad Ebrahimian Schnitt Hassan Hassandoost Ton Yadollah Najafi Mischung Mohammad Reza Delpak Musik Hossein Alizadeh Ausstattung, Kostüm Asghar Nezhad- Imani Maske Saeed Malekan Spezialeffekte Mohsen Rouzbehani THE SONG OF SPARROWS Regieassistenz Sirpous Hassanpour Karim arbeitet auf einer Straußenfarm. Er hat ein kleines Haus am Stadtrand Produktionsltg. Kamran Majidi Produzent Majid Majidi und kommt mit seinem Verdienst gut aus. Doch dann läuft ein Strauß da - Ausführender von und Karim, der schuld daran sein soll, wird entlassen. Aus Sorge um Produzent Javad Norouzbeigi sein finanzielles Fortkommen macht er sich auf die Suche nach dem Vogel, kann ihn jedoch nirgends finden. Als er eines Tages in die Stadt fährt, um Produktion dort das Hörgerät seiner Tochter reparieren zu lassen, nimmt er auf dem Majidi Film Production Suite 6, 2nd Floor, No. 2, Fourth Alley, Rück sitz seines Motorrads einen Mann mit und lässt sich dafür von ihm be - Gandi Street zahlen. In Anbetracht des guten Verdienstes setzt er diese Transporte nun IR-Tehran 1434894163 regel mäßig fort. Täglich fährt er in die Stadt und bringt bei der Rückkehr Tel.: +98 21 23276741 allerlei Trödel mit – alte Möbel, Autoersatzteile und Ähnliches. Fax: +98 21 88081647 Durch seinen Kontakt mit den Stadtbewohnern und den dortigen Ver hält - [email protected] nissen verändert sich Karims Persönlichkeit. -

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #952

Issue No. 952, 28 October 2011 Articles & Other Documents: Featured Article: U.S. Releases New START Nuke Data 1. 'IAEA Report Can Stymie Iran-P5+1 Talks' 2. German Wavers over Sale of Sub to Israel: Report 3. Armenian Nuclear Specialists Move to Iran for Better Life 4. Seoul, US Cautiously Move on 6-Party Talks 5. N. Korea Remains Serious Threat: US Defence Chief 6. Seoul, Beijing Discuss NK Issues 7. Pentagon Chief Doubts N. Korea Will Give Up Nukes 8. U.S.’s Panetta and South Korea’s Kim Warn Against North Korean Aggression 9. Pakistan Tests Nuclear-Capable Hatf-7 Cruise Missile 10. Libya: Stockpiles of Chemical Weapons Found 11. U.S. Has 'Nuclear Superiority' over Russia 12. Alexander Nevsky Sub to Be Put into Service in Late 2012 13. New Subs Made of Old Spare Parts 14. Successful Test Launch for Russia’s Bulava Missile 15. Topol Ballistic Missiles May Stay in Service until 2019 16. U.S. Releases New START Nuke Data 17. Army Says Umatilla Depot's Chemical Weapons Mission Done 18. Iran Dangerous Now, Imagine It Nuclear 19. START Treaty: Never-Ending Story 20. The "Underground Great Wall:" An Alternative Explanation 21. What’s Down There? China’s Tunnels and Nuclear Capabilities 22. Visits Timely and Important 23. Surgical Strikes Against Key Facilities would Force Iran to Face Military Reality 24. KAHLILI: Iran Already Has Nuclear Weapons Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

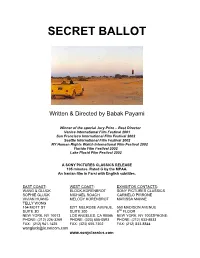

Secret Ballot

SECRET BALLOT Written & Directed by Babak Payami Winner of the special Jury Prize – Best Director Venice International Film Festival 2001 San Francisco International Film Festival 2002 Seattle International Film Festival 2002 NY Human Rights Watch International Film Festival 2002 Florida Film Festival 2002 Lake Placid Film Festival 2002 A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE 105 minutes. Rated G by the MPAA. An Iranian film in Farsi with English subtitles. EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: WANG & GLUCK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SOPHIE GLUCK MICHAEL ROACH CARMELO PIRRONE VIVIAN HUANG MELODY KORENBROT MARISSA MANNE TELLY WONG 154 MOTT ST 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE SUITE 3D SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10013 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022PHONE: PHONE: (212) 226-3269 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 941-1425 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 [email protected] www.sonyclassics.com Cast Girl NASSIM ABDI Soldier CYRUS AB YOUSSEF HABASHI FARROKH SHOJAII GHOLBAHAR JANGHALI Crew Written and Directed by BABAK PAYAMI Based on an idea by MOSHEN MAKHMALBAF Produced by MARCO MÜLLER & BABAK PAYAMI Executive Producer HOOSHANGH PAYAMI Director of Photography FARZAD JODAT Sound recordist YADOLLAH NAJAFI Sound Designer MICHAEL BILLINGSLEY Editor BABAK KARIMI a.m.c. Original Music MICHAEL GALASSO 2 SECRET BALLOT Synopsis An unsuspecting soldier awakens to discover that he can forget about another uneventful day at his lonely seaside post. It’s Election Day! A ballot box is parachuted down as a young woman pulls up to the shore of the remote island. To the soldier’s surprise, she’s actually the government bureaucrat in charge of local voting. -

The National Herald a Weekly Greek-American Publication 1915-2016 VOL

Greek Independence Day Parade In New York This Sunday! Let's All Attend! S o C V st ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 101 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 anniversa ry N The National Herald www.thenationalherald.com A weekly Greek-AmericAn PuBlicATion 1915-2016 VOL. 20, ISSUE 1015 March 25-31, 2017 c v $1.50 Greek Architect Wants Dr. Yancopoulos, Grand Marshal, Talks to TNH to Change Skyline of Regeneron’s founding scientist to Manhattan lead the NY parade TNH Staff deposited daily by their inhabi - TNH Staff tants,” Oiio founder Oikonomou NEW YORK – In response to the told Time Out New York. NEW YORK – Dr. George Yan - swathe of supertall luxury resi - “Architects are now free from copoulos, President and Chief dential towers rising in New the old constraints and are scientific officer of the pharma - York, local studio Oiio owned ready to wrestle with a city fab - ceutical company Regeneron, is by Ioannis Oikonomou has pro - ric covered by layers on top of the Grand Marshal for the Greek posed a conceptual skyscraper layers, made of meaning and Independence Parade on March that loops over to boast length memory.” 26 in New York. One of the lead - rather than height. THE BIG BEND ing scientists and the head of The Big Bend would be There is an undeniable ob - one of the largest pharmaceuti - formed from a very thin struc - session that resides in Manhat - cal companies listed on the New ture that curves at the top and tan. It is undeniable because it York Stock Exchange, Dr. -

2006-07 Annual Report

����������������������������� the chicago council on global affairs 1 The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, founded in 1922 as The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, is a leading independent, nonpartisan organization committed to influencing the discourse on global issues through contributions to opinion and policy formation, leadership dialogue, and public learning. The Chicago Council brings the world to Chicago by hosting public programs and private events featuring world leaders and experts with diverse views on a wide range of global topics. Through task forces, conferences, studies, and leadership dialogue, the Council brings Chicago’s ideas and opinions to the world. 2 the chicago council on global affairs table of contents the chicago council on global affairs 3 Message from the Chairman The world has undergone On September 1, 2006, The Chicago Council on tremendous change since Foreign Relations became The Chicago Council on The Chicago Council was Global Affairs. The new name respects the Council’s founded in 1922, when heritage – a commitment to nonpartisanship and public nation-states dominated education – while it signals an understanding of the the international stage. changing world and reflects the Council’s increased Balance of power, national efforts to contribute to national and international security, statecraft, and discussions in a global era. diplomacy were foremost Changes at The Chicago Council are evident on on the agenda. many fronts – more and new programs, larger and more Lester Crown Today, our world diverse audiences, a step-up in the pace of task force is shaped increasingly by forces far beyond national reports and conferences, heightened visibility, increased capitals. -

The New Hampshire Tnhdigital.Com Monday, March 7, 2016 Vol

Serving the University of New Hampshire since 1911 The New Hampshire TNHdigital.com Monday, March 7, 2016 Vol. 105, No. 35 Opinion: This week’s “From UNH exited the Hockey East Playo s in the INSIDE the Right” explores diversity rst round at Merrimack College. in the GOP. THE NEWS Page 12 Page 16 Student orgs collaborate, bring DarkMa er to UNH By RAOUL BIRON STAFF WRITER Hoping to foster solidarity, inspiration and acceptance, author and activist Dan Savage told LGBTQ+ youth around the world that “it gets better.” Since releasing his initial video in 2011, Savage’s message has exploded into a kind of marketed rallying cry for LGBTQ+ causes rang- ing anywhere from marriage equality to teen suicide. What happens when a three-word sentence - even one spoken on camera by hundreds of thousands - stops being enough? For Brooklyn based spoken word duo, DarkMatter, it gets bitter. On April 1, the fi rst day of UNH Campus Pride Month, the trans South Asian art and activist collaboration will occupy the Strafford room in the MUB. Sponsored in part by MUSO, UNH Alliance, Trans UNH, and The Kidder Fund, the event is largely designed to ignite a community-wide dialogue about perspective, the nature of privilege, and the missed subtleties of political movements as wide-ranging and general as LGBTQ+ rights. “We try to bring programs, artists and speakers that have a social justice-centered message because as a group we really believe in inclu- sion and activism,” said a spokesperson for MUSO. “We rarely get speakers who encompass multiple marginalized COURTESY PHOTO DARKMATTER DarkMatter, the trans South Asian art and activist duo, will speak in the Stra ord Room on April 1. -

Iran's Insurgencies Swell Amid Continuing Proxy Wars with Saudis

August 7, 2016 15 News & Analysis Iran Iran’s insurgencies swell amid continuing proxy wars with Saudis Ed Blanche Faisal, called for “the downfall of gained prominence on the battle- the Iranian regime”. The plea was field, external powers have taken made at a Paris conference of the a greater interest in them. Com- Beirut Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK), an op- bined, these factors help to explain position group that helped Ayatol- the revival of Kurdish insurgencies ne of the first things that lah Ruhollah Khomeini secure his in Iran.” Iran’s new armed forces Islamic revolution in 1979 and then Internal security threats in Iran chief, Major-General turned against him. tend to be under-reported because Mohammad Hossein The prince’s call to arms was of- of regime restrictions but that en- Bagheri, pledged when fensive enough for Tehran but to gagement was only one of many Ohe was appointed by Supreme do so at a gathering of the clerical skirmishes in recent months be- Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei regime’s sworn enemies, how- tween non-Shia Iranian insurgent was to reassure his countrymen ever past their prime they may groups and the IRGC. that simmering insurgencies on be, incensed the Iranian leader- On June 29th, the semi-official the Islamic Republic’s periphery ship. Mohsen Rezaie, a former Is- Fars news agency reported the Saudi Prince Turki al-Faisal looks on during the National Council were “under complete control”. lamic Revolutionary Guards Corps IRGC killed 11 Kurdish “coun- of Resistance of Iran (CNRI) annual meeting in Le Bourget, near However, he stressed that these (IRGC) commander and currently ter-revolutionary bandits” and Paris, last July. -

ISLAMIC MOVEMENT JO[Frnal

TWENTY FIVE CENTS SPRING TWO • VOLUME ON"E THE- ISLAMIC MOVEMENT JO[fRNAL COVERAGE~~~~ ' INSIDE Editorial - - -- - -- -- Page 2 Ideoiogical Sour ces - -- - -- Page 10-11 Islam in West Africa - - --- Page 3-5 War In Islam - - - - - - - - - Page 12 Salat - - - - -- - - - ---- Page 6 Intoxicating Drinks - - - - - - Page 13 Muslim African Statistics - - - Page 6 Endurance - - - - -- - - - -- - Page 14 Israel in Afri ca - - - - - Page 7. Book Review - ----- --- - Page 16 Muslim Liberation Fronts - Page 8 Letters &Adve r tisements - - - Page 18-19 Secretary General Speaks - Page 8 I - EDITORIAL OUST RA UF - Heresy Conde!111led The Islamic Party in North America expresses shock at the appalling revelation in the May 12, 1972, issue of Muhammad Speaks newspaper (pp. 3,4) of the Director of Washington's Islamic Center, Dr. M. Abdul Rauf, speaking in support of the organization and activities of the heretical "Black Muslims." At a New York rally protesting police brutality in their Ha~lem ''temple" he declared: ''We have come to express our admiration for your work and the great achievements of the beloved leader, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. I would like to assure you all that the whole Muslim world, which includes 700 million people is behind you." It is also painful to Muslims that the esteemed Qur'anic reader, Shaikh Mahmoud El Hussary, was with him at this time. The Islamic Party is not at odds with anyone's efforts to effect change and relief of oppression in the black community, and we believe that application of Islam is the best way to accomplish this. It should be clear to all that the issue under attack here is the total misrepresentation of Islam, as condoning or supporting un-Islam. -

Pessuto Kelen M.Pdf

ii UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ARTES KELEN PESSUTO O ‘ESPELHO MÁGICO’ DO CINEMA IRANIANO: UMA ANÁLISE DAS PERFORMANCES DOS “NÃO” ATORES NOS FILMES DE ARTE Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Artes, da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Artes. Área de concentração: Artes Cênicas. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Francirosy Campos Barbosa Ferreira CAMPINAS 2011 iii . . . . . . .. iv v vi Dedico essa dissertação à memória dos meus pais, Agueda e José Pessuto, que são os espelhos da minha vida. À minha sobrinha Gabriela, por existir e fazer a minha vida mais feliz. À minha orientadora e amiga Francirosy C. B. Ferreira, por tanta afeição e apoio. vii viii AGRADECIMENTOS À Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), pelo financiamento desta pesquisa, que permitiu minha dedicação exclusiva e o acesso ao material. Agradeço também aos pareceristas, que acreditaram no projeto. À minha mãe Agueda Pessuto, que tanto incentivou minha carreira, que fez sacrifícios enormes para que eu me formasse, tanto no teatro, quanto na faculdade. Sempre expressou sua admiração e carinho. Muito amiga e companheira, que mesmo não estando presente entre nós, é o guia da minha vida. Espero ser um por cento do que ela foi. Nunca me esqueço que horas antes dela morrer, pediu para eu ler menos e dar mais atenção para ela, não cumpri o que pediu... No dia seguinte à sua morte ocorreu o exame para ingressar no mestrado. Passar foi uma questão de honra para mim. Eis que termino essa pesquisa e lhe agradeço, pois se não fosse esse exemplo de mulher batalhadora no qual me inspiro, não teria conseguido. -

Kandahar Av Mohsen Makhmalbaf Iran 2001, 85 Minuter Nafas Är En

Kandahar av Mohsen Makhmalbaf Iran 2001, 85 minuter Nafas är en ung journalist från Afghanistan som lever i exil i Kanada. Hon får ett desperat brev från sin syster som fortfarande är kvar i Afghanistan och som planerar att ta sitt liv under den åstundande solförmörkelsen. Hon ger sig genast av mot Kandahar för att rädda sin syster. Hon reser till Iran, och därifrån måste hon bege sig över gränsen. Som ensam kvinna kan hon inte ta sig någonstans, och under resans gång får hon hjälp av fyra guider, som på olika sätt representerar det talibanska förtrycket; en äldre flykting från Afghanistan, en liten pojke som blivit relegerad från koranskolan, en svart amerikan som arbetar som läkare i öknen och en enarmad man som skadats av en landmina. Bakgrund För några år sedan blev den iranske regissören Mohsen Makhmalbaf uppsökt av en afghansk kvinna bosatt i Kanada. Niloufar Pazira hoppades att han skulle ha kontakter som kunde hjälpa henne att ta sig över gränsen till sitt forna hemland. Ärendet brådskade eftersom brevet som föranlett hennes avresa avslöjade att väninnan i Afghanistan var på väg att ta sitt liv. Niloufar Pazira släpptes aldrig in i Afghanistan och tvingades återvända till Kanada. Även om Mohsen Makhmalbaf inte hade kunnat hjälpa henne hade han svårt att släppa hennes historia. Han intresserade sig så mycket för den att han började studera och undersöka Afghanistan i skrifter, böcker och dokumentärfilmer. Något år senare sökte han upp Niloufar Pazira för att erbjuda henne huvudrollen i den film som skulle ta avstamp i hennes berättelse. Mohsen Makhmalbaf talar om Afghanistan som ”landet utan bilder”.