Dallas, TX: the Staggering Wealth Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Uptown Demographic Study

Uptown Dallas Prepared for Uptown Dallas, Inc. Market Study December 2019 Metrostudy-Dallas/Ft. Worth 1255 West 15th Street, Suite 240 Plano, TX 75075 Phone: 214.869.4916 Email: [email protected] Web: www.metrostudy.com Table of Contents Profile 3 – 8 Economic/Demographic 7 – 11 Employment 12 – 14 Real Estate 15 – 21 Transportation 22 – 24 Uptown Data 25 – 28 Uptown Residents 29 – 37 UPTOWN DALLAS, INC. CUSTOM STUDY Page 2 Profile Uptown Dallas 1993 Development in Uptown began in the 1980s with residential and commercial growth. As the neighborhood began to take shape, developers and residents alike saw an opportunity to enhance the area. Through consensus with the City of Dallas, Uptown Dallas, Inc. was formed in 1993 to scale, maintain and further improve the neighborhood. Uptown Dallas, Inc. celebrated 25 years in 2018. 591.8 Acres Stretching just under one square mile, or 591.8 acres, Uptown is a diverse and dense neighborhood. The community includes numerous residential options, reputable companies, schools and a variety of retail and dining options. 58.1 Acres Uptown has 19 square feet of greenspace per person totaling 58.1 acres. Open space includes Griggs Park which is 8 acres and Greenwood Cemetery, Calvary, Temple Emanuel, Anita Phelps Park and Freedman’s Memorial comprise 44 acres. Katy Trail, a 3.5-mile, privately funded trail system built on an old railroad line defines Uptown’s western border. Additionally, there are 53.5 acres of greenspace bordering Uptown including the award-winning Klyde Warren Park. 4.6 Miles Founded in 1983 with the intent of returning heritage streetcars to the streets of Uptown, the McKinney Avenue Transit Authority successfully accomplished that goal in July of 1989. -

Postwar Urban Redevelopment and North Dallas Freedman's Town

Roads to Destruction: Postwar Urban Redevelopment and North Dallas Freedman’s Town by Cynthia Lewis Like most American cities following World War II, Dallas entered a period of economic prosperity, and city leaders, like their counterparts throughout the nation, sought to maximize that prosperity through various urban renewal initiatives.1 Black urban communities across the country, branded as blighted areas, fell victim to the onslaught of postwar urban redevelopment as city leaders initiated massive renewal projects aimed at both bolstering the appeal and accessibility of the urban center and clearing out large sections of urban black neighborhoods. Between the years 1943 and 1983, Dallas city officials directed a series of massive redevelopment projects that decimated each of the city’s black communities, displacing thousands and leaving these communities in a state of disarray.2 This paper, which focuses on the historically black Dallas community of North Dallas, argues that residential segregation, which forced the growth and evolution of North Dallas, ultimately led to the development of slum conditions that made North Dallas a target for postwar slum clearance projects which only served to exacerbate blight within the community. Founded in 1869 by former slaves, North Dallas, formerly known as Freedman’s Town, is one of the oldest black neighborhoods in Dallas.3 Located just northeast of downtown and bounded by four cemeteries to the north and white-owned homes to the south, east, and west, the area became the largest and most densely populated black settlement in the city. Residential segregation played a pivotal role in the establishment and evolution of North Dallas, as it did with most black urban communities across the country.4 Racial segregation in Dallas, with its roots in antebellum, began to take 1 For an in-depth analysis of the United States’ postwar economy, see Postwar Urban America: Demography, Economics, and Social Policies by John F. -

Bob Mong, President University of North Texas – Dallas

The Rotary Club THE HUB of Park Cities Volume 67, Number 33 www.parkcitiesrotary.org March 18, 2016 Serving to Make a Difference Since 1948 TODAY’S PROGRAM Program Chairs of the Day: Ed Fjordbak Bob Mong, President University of North Texas – Dallas Robert Mong, recently retired editor of The Dallas Morning While serving as The Newsʼ managing editor, Mong chaired News, has been named the sole finalist for president of the Uni- the minorities committee of what is now the American Society of versity of North Texas Dallas. News Editors. He also chaired the societyʼs Human Resources During his 36-year career at The News , Mong served as the Committee. paperʼs managing editor and later as editor in chief. During his In 2014 Mong was instrumental in attracting a $250,000 time in news leadership, the paper won nine Pulitzer Prizes and grant from the Knight Foundation to create the Hispanic Families named Pulitzer finalist sixteen other times. He also gained signifi- Network. The network trains Hispanic parents in three Dallas cant business experience as the paperʼs general manager for neighborhoods to report on early childhood education issues. three years and before that as CEO and publisher of the then The News partnered with SMU to train participating parents. company owned Owensboro (Ky) Messenger- Inquirer. Mong served as chairman of The Dallas Morning News Throughout his professional career, higher education has Charities from 1998 to 2015, raising money for the hungry and been the principal outlet for his volunteer activities. He has devel- homeless in North Texas. oped volunteer ties to UNT Denton, UT-Arlington, UT-Dallas, SMU, In 2004, he won the national Empathy Award, sponsored by Austin College, UT-Austin and LSU – among other institutions. -

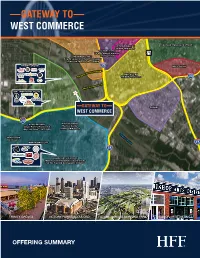

West Commerce Gateway To

GATEWAY TO WEST COMMERCE UPTOWN DALLAS BAYLOR MEDICAL DISTRICT 22,000 employees VICTORY PARK 75-acre master-planned DESIGN DISTRICT development Fourth largest portfolio of designer showroom space in the country TRINITY GROVES DEEP ELLUM Bridge nt Hill Hu ret DALLAS CBD rga Ma 113,000 employees West Commerce St FORT WORTH AVE RETAIL GATEWAY TO CEDARS WEST COMMERCE KESSLER PARK Methodist Dallas Single Family Residential Medical Center Avg. List Price - $675,000 2,900+ Employees TRINITY RIVER Stevens Park Golf Course NORTH OAK CLIFF BISHOP ARTS DISTRICT 100+ Restaurants & Retail Destinations 7 of the Top 100 Restaurants in Dallas TRINITY GROVES VICTORY PARK/DALLAS CBD FUTURE HAROLD SIMMONS PARK BISHOP ARTS DISTRICT OFFERING SUMMARY In ment Overview HFF has been exclusively retained to offer an opportunity for qualified investors to purchase the fee simple interest in a site known as Gateway to West Commerce (the “Site”). The 4.75-acre site is located in Trinity Groves at the SW corner of W Commerce Street and N Beckley Avenue. The Site is located in the Planned Development District 714, allowing for a variety of uses including office, retail, and apartments. Gateway to West Commerce boasts excellent access to Dallas’ Airports and primary traffic arteries as well as close proximity to a wide array of lifestyle amenities including the acclaimed Trinity Groves, Victory Park, Bishop Arts District, and more. Additionally, Gateway to West Commerce is located just minutes from Downtown Dallas (approximately 1 mile from the Site). This highly visible location represents a unique opportunity to acquire/develop in an infill location with access to the best economic drivers the city has to offer. -

Dfw Private Schools Private Schools

DFW PRIVATE SCHOOLS PRIVATE SCHOOLS COLLIN COUNTY All Saints Catholic School 7777 Osage Plaza Parkway, Dallas, TX 75252 214.217.3300 PK-8 Ann & Nate Levine Academy 18011 Hillcrest Road, Dallas, TX 75252 972.248.3032 PK-8 Bethany Christian School 3300 W Parker Road, Plano, TX 75075 972.596.5811 K-12 Bridge Builder Academy 520 Central Pkwy East #101, Plano, TX 75074 972.516.8844 K-12 Canyon Creek Christian Academy 2800 Custer Parkway, Richardson, TX 75080 972.231.4890 PK-12 Castle Montessori of McKinney 6151 Virginia Parkway, McKinney, TX 75070 972.592.1222 PK-3 Celina Christian Academy PO Box 389, Celina, TX 75009 972.382.2930 K-6 Centennial Montessori Academy 7508 W Eldorado Parkway, McKinney, TX 75070 972.548.9000 K-4 Children’s Carden Montessori 8565 Gratitude Tr, Plano, TX 75024 972.334.0980 NS-3 Christian Care Academy PO Box 1267, Anna, TX 75409 214.831.1383 PK-4 Coram Deo Academy of Collin County 2400 State Highway 121, Plano, TX 75025 972.268.9434 K-11 Cornerstone Christian Academy 808 S. College Street, McKinney, TX 75069 214.491.5700 PK-12 Faith Christian Academy 115 Industrial Blvd A, McKinney, TX 75069 972.562.5323 PK-12 Faith Lutheran School 1701 East Park Boulevard, Plano, TX 75074 972.243.7448 PK-12 Frisco Montessori Academy 8890 Meadow Hill Dr, Frisco, TX 75033 972.712.7400 PK-5 Good Shepherd Montessori School 7701 Virginia Pkwy, McKinney, TX 75071 972.547.4767 PK-5 Great Lakes Aademy (Special Ed) 6000 Custer Rd, Bldg 7, Plano, TX 75023 972.517.7498 1-12 Heritage Montessori Academy 120 Heritage Parkway, Plano, TX 75094 972.424.3137 -

November 5, 2019 Dallas County Vote Centers 1 VC# LOCATION Room

November 5, 2019 Dallas County Vote Centers VC# LOCATION Room ADDRESS CITY ZIP VC213 ADDISON FIRE STATION # 1 TRAINING ROOM 4798 AIRPORT PKWY ADDISON 75001 VC212 ADDISON FIRE STATION # 2 BAY 3950 BELTWAY DR ADDISON 75001 VC161 LOOS FIELD HOUSE MAIN LOBBY 3815 SPRING VALLEY RD ADDISON 75001 VC424 BALCH SPRINGS CIVIC CENTER MEETING ROOM 12400 ELAM RD BALCH SPRINGS 75180 VC307 BALCH SPRINGS RECREATION CENTER MEETING ROOM 4372 SHEPHERD LN BALCH SPRINGS 75180 VC305 HICKORY TREE BAPTIST CHURCH FELLOWSHIP HALL 3200 HICKORY TREE RD BALCH SPRINGS 75180 VC306 HODGES ELEM SCHOOL STAGE 14401 SPRING OAKS DR BALCH SPRINGS 75180 VC168 BLANTON ELEM SCHOOL LIBRARY 2525 SCOTT MILL RD CARROLLTON 75006 VC172 CROSBY RECREATION CENTER ELF FORK 1610 E CROSBY RD CARROLLTON 75006 VC451 JERRY R. JUNKINS ELEM SCHOOL LIBRARY, ROOM 111 2808 RUNNING DUKE DR CARROLLTON 75006 VC171 JOSEY RANCH LAKE LIBRARY MEETING RM 150 1700 KELLER SPRINGS RD CARROLLTON 75006 VC170 KELLER SPRINGS BAPTIST CHUR FELLOWSHIP HALL 3227 KELLER SPRINGS RD CARROLLTON 75006 VC167 MCCOY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL GYM 2425 MCCOY RD CARROLLTON 75006 VC169 NEWMAN SMITH HIGH SCHOOL KEATON THEATER LOBBY 2335 N JOSEY LN CARROLLTON 75006 VC173 NORTH DALLAS FAMILY CHURCH GYM 1700 S JOSEY LN CARROLLTON 75006 VC174 TED POLK MIDDLE SCHOOL G104 2001 KELLY BLVD CARROLLTON 75006 VC279 BESSIE COLEMAN MIDDLE SCHOOL LIBRARY 1208 E PLEASANT RUN RD CEDAR HILL 75104 VC456 BRAY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL GYM 218 N BROAD ST CEDAR HILL 75104 VC428 CEDAR HILL GOVERNMENT CENTER-BLDG 100 LOBBY 285 UPTOWN BLVD CEDAR HILL 75104 VC278 L.K. -

Northwest Corridor

NORTHWEST CORRIDOR NORTHWEST CORRIDOR AT A GLANCE tunnel miles elevated miles 13,900 48,000 2004-10 12 at-grade Weekday Riders Jobs Within 1/2 Mile of Stations Phased Openings Total Stations 17.4 0.3 41minutes 1 $700m 17.4 miles 8.4 Downtown Dallas to Airport Connection at Federal Funding for Combined Downtown Dallas to 8.7 N Carrollton/Frankford Station Inwood/Love Field Station NW/SE Project N Carrollton/Frankford Station 0% 48% MILES AT-GRADE 50% 8.7 DAILY STATION RIDERSHIP**Average Weekday FY18 MILES ELEVATED 3,000 8.4 2,500 2,000 MILES 1,500 BELOW-GRADE 0.3 1,000 500 0 MARKET VICTORY INWOOD/ BURBANK CENTER BACHMAN DENTON ROYAL LANE DOWNTOWN LOVE FIELD WALNUT HILL/ TRINITY MILLS FRANKFORD SMD/PARKLAND CARROLLTON FARMERS BRANCH N. CARROLLTON/ PROJECT TIMELINE SERVICE CHARACTERISTICS FEBRUARY NOVEMBER NORTHWEST 2000 2004 LOCALLY PREFERRED FIRST 1.2 MILES GREEN LINE 7.5-MINUTE COMBINED ALTERNATIVE OPENS TO VICTORY 15-MINUTE PEAK HEADWAY APPROVED STATION PEAK (GREEN/ORANGE) HEADWAY SOUTH OF BACHMAN ORANGE LINE BUS INTERFACE AT 15-MINUTE ALL STATIONS 2010 PEAK HEADWAY 2000 2003 2004 2006 TO PARKER RD STATION OCTOBER JULY DECEMBER ORANGE LINE JUNCTION 2003 2006 2010 20-30 MINUTE AT BACHMAN STATION FEIS PUBLISHED FTA AWARDS GREEN LINE OFF-PEAK $700M GRANT FOR OPENS HEADWAY COMBINED NW/SE PROJECT TRE AT VICTORY STATION DID YOU KNOW? The Northwest Corridor provides direct access to Parkland Hospital and serves the largest medical district in the DFW region, UTSW Medical District. REV. 03/19 STATION HIGHLIGHTS VICTORY • AMERICAN AIRLINES CENTER • PEROT MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE A-Train to Denton (operated by DCTA) NW PLANO PARK & RIDE PLANO MARKET CENTER • DALLAS MARKET CENTER P • INFOMART PARKER ROAD JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CTR. -

Documentation of Public Hearing

Documentation of Public Hearing Project Location Dallas County Interstate Highway 635 (I-635) CSJs: 2374-01-137; 2374-01-183; 2374-02-053; 2374-02-152; 2374-02-153; 2374-01-190; 2374-01-191; 2374-02-171 Project Limits From United States Highway 75 to I-30 Hearing Location Highland Oaks Church of Christ 10805 Walnut Hill Lane, Dallas, Texas 75238 Hearing Date and Time July 18, 2019 at 6:00 p.m. Translation Services Spanish Presenters Ceason Clemens, P.E., Deputy District Engineer for the TxDOT Dallas District Elected Officials in Attendance Theresa Daniel, Dallas County Commissioner, District 1 Rich Aubin, City of Garland Mayor Pro Tem Representative for Adam McGough, City of Dallas Deputy Mayor Pro Tem Total Number of Attendees (approx.) 65 (3 elected officials, 62 public) Total Number of Commenters 10 Contents A. Comment/response matrix B. Notices provided (including tear sheets, website screen captures, distribution lists with copy of notice sent, etc.) C. Sign-in sheets 760.06.TEM D. Transcript E. Comments received F. Figures 760.06.TEM Section A. Comment/Response Matrix for the I-635 LBJ East Public Hearing Document Pages Alphabetic Index of All Commenters 1 Comment/Response Matrix 7 Alphabetical List of Commenters Comment Number Commenter Name 1 Barron Jr., Moss Lee 2 Bookhout, Jim 3 Boyd, Bill 4 Edwards, Steve 5 Ferguson, Dorothy 6 Jones, David J. 7-8 Lawrence, Patricia 9-10 Lindberg, Eric 11-13 Lindberg, Sharon 14 Morgan, Susan I-635 LBJ East Public Hearing Comment Response Matrix Comment Commenter Date Source Comment Topic Response Number Name Received This important project is needed for the east Dallas & Garland areas. -

Victory Park

SOUTH VICTORY DISTRICT Victory Park DALLAS, TEXAS Victory Park, a walkable, urban development in the Uptown neighborhood of Dallas, is home to some of the cities best restaurants, entertainment, and retail. • Victory Park is a 75 acre masterplanned, mixed-use development in Downtown Dallas anchored by the American Airlines Center (home of the Dallas Mavericks & Stars), The House of Blues, HERO, Tom Thumb, W Dallas Hotel and the new 44,000 SF Cinepolis Luxury Cinemas. • The bar and restaurant scene at Victory Park is about to experience a dramatic change as we welcome new concepts, opening later this year, from some of Dallas' top food and beverage operators. • WeWork opened in early 2019 on the 2nd & 3rd floors of the Victory Plaza Office building. The space features their signature mid-century modern decor, open floor plan, floor to ceiling glass and steel framing, private office suites and communal working space. 2 Demographics DALLAS LOVE NORTHEAST FIELD AIRPORT PARK DALLAS CITIES 1 MI RADIUS GREENWAY Population (2018) – 29,603 PARKS 75 Households – 13,124 Avg. HH Income – $117,552 3 MILES Median Age – 33 Daytime Demo – 141,525 Education (Bach+) – 57% 3 MI RADIUS 35E Population (2018) – 187,692 Households – 87,023 1 MILE Avg. HH Income – $91,322 Trinity UPTOWN OLD EAST Median Age – 34 River DALLAS Daytime Demo – 393,259 30 Education (Bach+) – 48% Victory Park 5 MI RADIUS Deep DOWNTOWN Ellum Population (2018) – 398,518 DALLAS Households – 163,296 Avg. HH Income – $94,878 CEDARS Median Age – 34 Daytime Demo – 642,221 30 Education (Bach+) -

GACIES a His to J ~F Journal for Dnllns & North Centml Texns

....... .....,...GACIES A His to J ~f Journal for Dnllns & North Centml Texns DEPARTMENTS Deadly Dallas Streets 4 l:lv RusTY Wu.I.IAMS From the Editor Out of Many, One 3 18 Bv M ARK RtcE Photo Credits The Impact of Transportation 26 on Historic Ethnic Neighborhoods 56 Bv I'ATtuctA Ilt cKs, JuA tTA II . 1/\Nt;'l., A t>Rt cK Lo ~;ssBmtc Contributors 38 Braniff Airways Took Dallas to New Heights 59 Bv D AVI D PttEztost Dallas Then and Now George Schrader: 50 Conversation with a History Maker 60 'l'tlANSCRIBED AND WITEIJ BY STIII'IIEN F ACIN All pn:vions issues of LRxncies fiu m 19R\I through 201 7 .1re online Jt the University of North Texas Portal to Texas History. The address is: h ttp:lI tt"xashistory.um.edu/ explore/ coll <•ctions/LHJNT Historic Ethnic Neighborhoods g~borhoods are typically created and Two historic ethnic Dallas neighborhoods int-luenccd by a number of fa ctors like geography, O ld North Dallas and La DJjada-demonstrJtc <:cono mics, and the availability of tra nsportation. hovv these various fac tors came together and However, tor people of color who lived in Dallas how decisions pertaining to transportation made prior to the latter part of the t\oventicth century, by the Anglo population both assisted and Llter the law of segregation and the dominant social threatened these neighborhoods. O ld North attitudes of the much larger Anglo community Dallas, w hich was located just north ofdowntown, heavily inAuenced the origination and existence was established in the 1fl60s as J freedmen's of minority neighborhoods. -

DFW Industrial Marketview

MARKETVIEW Dallas/Fort Worth Industrial, Q4 2018 Demand tops 20 million sq. ft. for third consecutive year. 6.0% 14,513,927 SF 8,273,325 SF 7,108,176 SF Figure 1: DFW Industrial Market *Arrows indicate trend from previous quarter. MSF Vacancy Rate (%) 30 7 25 20 15 6 10 5 0 5 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Total Net Absorption Delivered Construction Construction Starts Total Vacancy Source: CBRE Research, Q4 2018. SUPPLY AND DEMAND REMAIN BALANCED PRODUCT PIPELINE CONTRACTS SUBSTANTIALLY MARKET-WIDE VACANCY RATE REMAINS SNUG Q4 2018 CBRE Research © 2019 CBRE, Inc. | 1 MARKETVIEW DALLAS/FORT WORTH INDUSTRIAL Figure 2: DFW Industrial Market Snapshot Net Direct Total Q4 2018 Q4 2018 2018 Avail. Direct Total Rentable Available Vacancy Vacancy Direct Net Total Net Total Market Rate Vacancy Vacancy Area (SF) Rate Rate Absorption Absorption Absorption (%) (SF) (SF) (SF) (%) (%) (SF) (SF) (SF) DFW Airport 76,537,446 7,143,995 9.3 4,981,889 6.5 5,496,992 7.2 1,021,613 1,093,964 2,816,521 East Dallas 36,711,061 3,247,617 8.8 1,640,650 4.5 1,674,582 4.6 455,405 421,473 323,735 Northeast Dallas 98,857,581 7,721,313 7.8 4,920,189 5.0 5,634,661 5.7 749,356 666,538 1,314,114 Northwest Dallas 110,278,941 6,873,465 6.2 4,158,527 3.8 4,433,034 4.0 360,646 333,645 1,007,725 South Dallas 77,278,616 13,465,000 17.4 12,086,981 15.6 12,226,952 15.8 1,206,291 1,254,279 5,847,155 South Stemmons 116,757,096 7,800,940 6.7 4,460,334 3.8 4,759,216 4.1 (375,470) (376,688) (1,290,388) Great SW/Arlington 111,266,798 8,018,274 7.2 5,043,620 4.5 5,140,768 4.6 2,566,998 2,601,478 7,293,671 North Ft. -

Oral History of Bonton and Ideal Neighborhoods in Dallas, Texas

ORAL HISTORY OF BONTON AND IDEAL NEIGHBORHOODS IN DALLAS, TEXAS Briana Payne Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2015 APPROVED: Andrew Nelson, Committee Chair Beverly Ann Davenport, Committee Member Matthew Durington, Committee Member Lisa Henry, Chair of the Department of Anthropology Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Payne, Briana. Oral History of Bonton and Ideal Neighborhoods in Dallas, Texas. Master of Arts (Applied Anthropology), December 2015, 145 pp., 3 tables, 67 figures, references, 223 titles. The Bonton and Ideal neighborhoods in Dallas Texas, developed in the early 1900s, experienced physical and social decay throughout the 1980s. Neighborhood organizations and resident activism were vital to the rebirth of the community in the 1990s. Current revitalization efforts taking place there have been a source of contention as the neighborhood continues to overcome inequalities created by decades of racialized city planning initiatives. This thesis focuses on how the structuring structure of whiteness has historically affected, and continues to affect, the neighborhoods of Ideal and Bonton, as well as acts to identify how black residents have navigated their landscape and increased their collective capital through neighborhood activism. Copyright 2015 By Briana Payne ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank the Neighborhood Investment Program for providing me with the opportunity to work with them as they continue to improve the Bonton and Ideal neighborhoods in South Dallas. Without their acknowledgement of the importance of conserving the history of this community, I would not have been able to share the important life stories of the residents.