The PSC Takes a Strike Vote the Union's First Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel Kugler, 1917-2007 to Organize at CUNY

12 NEWS Clarion | November-December 2007 After the Taylor Law of 1967 al- lowed for collective bargaining in public institutions in New York, Iz made an even more determined bid Israel Kugler, 1917-2007 to organize at CUNY. His efforts met strong opposition from man- agement and competition from an- By IRWIN YELLOWITZ other faculty organization, the PSC Retirees Chapter Pioneer of unionism in higher education Legislative Conference, headed by Belle Zeller. Israel Kugler, who died on October The rivalry between the organi- 1, was a pioneer, a visionary and an zations led to two collective bar- activist. Iz, as he was known to gaining units and contracts in 1969. everyone, believed in academic In 1972, the UFCT and Legislative unionism when few others did. He Conference merged to form the argued that faculty and profession- Professional Staff Congress. Belle al staff should be in one union to Zeller became president and Iz was maximize their bargaining power. the deputy president. The major He believed that this union should difference between the two groups be affiliated with the labor move- had been Iz’s insistence that an aca- ment and should not only serve the demic union had to be part of the needs and interests of its members larger labor movement. Iz achieved through collective bargaining, but this objective, as the new PSC also work to achieve social justice in rapidly became an influential local the nation at large. in the AFT. Iz was always an active leader who could rally support from many CONTINUED ACTIVISM sources, and he had the intelligence This power sharing arrangement and drive to carry through on his between Kugler and Zeller never program. -

Proceedings, First Annual Conference April 1973

PROCEEDINGS, FIRST ANNUAL CONFERENCE APRIL 1973 Maurice C. Benewitz, Editor Table of Contents Order of speeches for the Journal of the First Annual Conference of the Na tional Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education. Introduction Page Sidney Hook - The Academic Mission and Collective Bargaining 8 Robert J. Kibbee -A Chancellor Views Bargaining in Retrospect and Prospect ---------------------------------------------------- 18 David Selden - Unionism's Place in Faculty Life ___ _____ ________ _ 24 Donald H. Wollett- Historical Development of Faculty Collective Bar gaining and Current Extent__________________________________________________________________ 28 Terrence N. Tice -The Faculty Rights and Responsibilities Report: University of Michigan ______________ _ __ __________ _______________________________ ________ 41 Robert J. Wolfson - Productivity and University Salaries: How will Col- lective Bargaining be Affected? ___ ______________________________ __ _______ 52 Margaret K. Chandler and Connie Chiang - Management Rights Issues in Collective Bargaining in Higher Education____ ___________ 58 Israel Kugler - Creation of a Distinction Between Management and Faculty ____ _____ _______ ___ _____ _________________ _______ _____________________ 67 Tracy H. Ferguson - Certification of Units under Federal Law____ 72 Jerome Lefkowitz - Certification of Units in Higher Education 81 Charles Bob Simpson -Academic Judgement and Due Process__ 89 Milton Friedman - Special Issues in Arbitration of Higher Education Disputes: -

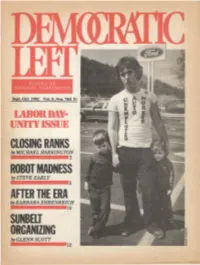

Closing Ranks Robot Madness After the Era Sunbelt Organizing

Sept.-Oct. 1982 Vol. X, Nos. 7A8. $1 l.JUICtll lt1lY· l~TIT L«i~"1JI~ CLOSING RANKS by MICHAEL HARRINGTON . ~· -~ - .· 3 ROBOT MADNESS by STEVE EARLY 5 AFTER THE ERA by BARBARA EHRENREICH 10 SUNBELT ORGANIZING by GLENN SCOTT 12 Toward Solidarity Day II By Michael !Ja rrington ABOR DAY 1982WASTHEMOSTlRITI cal celebration of that holiday Ill half a century, al least as far as American unions are concerned. The unions have begun lo respond The speeches and parades had new elements. What follows are one socialist's thoughts on where we are going, and where we should go. To begin with, let us summarize some basic themes familiar to readers of DEMOCRAT IC LEFT. The current crisis 1s structural in nature. That is, it is not one more cyclical downturn that will be followed by a return to "normalcy," but a destructive transformation of the very character of the economy. When "recovery" comes, hundreds of thousands of !'.tffHCO workers in basic industry will not return to ( 1 l• ••'.1'. their jobs. The jobs have been destroyed. --- == In the first phase of the Reagan adminis tration, th~ president- who did recognize that the crisis was structural-tried to deal with the situation through "supply-side" tax cuts ''No return to the past can bring us out ofthis national plight.. outrageously biased in favor of the corpora tions and the rich. The recipients of this lar gesse were supposed to invest and pull the Supply side economics failed to spur m Before turning to some thoughts on the proper economy out of its slump. -

Tw••1~Jlopl"T- Annl•IC~Nfer~Nee A:I.Fl;L~

~e~i'1P·. Tw••1~Jlopl"t- Annl•IC~nfer~nee A:i.Fl;l~ DOUCLAS,IJ. WilJtl, llir:.tor: . BJ!Tll ~~l\IANlti!IN~N, B()itor IDGllER EDUCATION COLLECTIVE BARGAINING: BACK TO "CB" BASICS Proceedings Twenty-Fourth Annual Conference April 1996 DOUGLAS H. WIDTE, Director BETH HILLMAN JOHNSON, Editor National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions School of Public Affairs, Baruch College, The City University of New York Copyright© 1996 in U. S. A. By the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions Baruch College, City University of New York All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Price: $45.00 ISSN 0742-3667 ISBN 0911259-34-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. vii Beth Hillman Johnson I. LEADERS SPEAK OUT ON HIGHER EDUCATION COLLECTIVE BARGAINING A. HIGHER EDUCATION COLLECTIVE BARGAINING: ISSUES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY ........................................... 3 Stephen Joel Trachtenberg B. HIGHER EDUCATION UNIONS IN A TIME OF CHANGE: COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION .......................................................... 10 Terry Jones C. RECENT TRENDS IN COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN CANADA .............................................................................. -

List of Refernces

SEWING THE SEEDS OF STATEHOOD: GARMENT UNIONS, AMERICAN LABOR, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL, 1917-1952 By ADAM M. HOWARD A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 Copyright 2003 by Adam M. Howard ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research and writing of this dissertation, spanning a period of five years, required assistance and understanding from a variety of individuals and groups, all of whom I wish to thank here. My advisor, Robert McMahon, has provided tremendous encouragement to me and this project since its first conception during his graduate seminar in diplomatic history. He instilled in me the courage necessary to attempt bridging three subfields of history, and his patience, insight, and willingness to allow his students to explore varied approaches to the study of diplomatic history are an inspiration. Robert Zieger, in whose research seminar this project germinated into a more mature study, offered tireless assistance and essential constructive criticism. Additionally, his critical assessments of my evidence and prose will influence my writing in the years to come. I also will always remember fondly our numerous conversations regarding the vicissitudes of many a baseball season, which served as needed distractions from the struggles of researching and writing a dissertation. Ken Wald has consistently backed my work both intellectually and financially through his position as the Chair of the Jewish Studies Center at the University of Florida and as a member of my committee. His availability and willingness to offer input and advice on a variety of topics have been most helpful in completing this study. -

American Educator, Winter 2013-2014

VOL. 37, NO. 4 | WINTER 2013–2014 www.aft.org /ae How Not to Go It Alone WAYS COLLABORATION CAN STRENGTHEN EDUCATION WHERE WE STAND PLAN NOW TO ATTEND THE AFT’S 16TH ANNUAL CENTER FORSchool Improvement LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE NEW YORK CITY | JANUARY 23–26, 2014 The American Federation of Teachers Center for School Improvement and the United Federation of Teachers Teacher Center have partnered to deliver an institute on facilitating school improvement through labor-management collaboration that results in higher student achievement. PARTICIPATING TEAMS INCLUDE: • School-level union representatives, • District personnel responsible for principals, members of school- facilitating school improvement improvement teams, and individuals in multiple schools jointly identified by with day-to-day responsibility for the district and union supporting school-level redesign • Members and community leaders • Union leadership or staff assigned to of district school-improvement teams support redesign at both the school and district levels To register online, go to www.aft.org/issues/schoolreform/csi/institute.cfm. Questions? Email [email protected]. WHERE WE STAND Pushing Forward Together RANDI WEINGARTEN, President, American Federation of Teachers I HAVE SEEN LABORMANAGEMENT those relationships are poor. Yet collabora- expert assistance to several school improve- relations at their best and at their worst. In tion is more the exception than the norm. ment eorts with collaboration at their core. fact, I’ve been party to both. In my early days Unfortunately, without partners on both We are ghting for the Common Core State Improvement as president of the United Federation of sides of the labor-management equation Standards to be implemented with, and not Teachers in New York City, I worked closely willing to put students at the forefront of imposed on, teachers, and for the needs of with the then-chancellor of the city’s public their concerns, signicant progress will be teachers and students to be rst and foremost schools to launch one of the most successful impeded, if not impossible. -

Thousands of Arab Refugees Flee in Wake of Israel's

ThousandsofArab Refugees Flee InWake of Israel's''Blitzkrieg'' THE Use of Napalm Infliefs MILITANTHeavy Toll in Jordan Published in the Interest of the Working People Vol. 31 - No. 25 Monday, June 19, 1967 Price 10¢ JohnsonStores DoubleGain wit/, Israel'sVi,tory By Harry Ring JUNE 14 - The victory of the ways higher than in Southeast Israeli army over the Arab peoples Asia. That's why, if the Israeli is proving a many-sided blessing forces had faltered, the U.S. stood for the Johnson administration ready to move in militarily even and a spur to its program to though already pinned down in a secure the domination of the U.S. major war in Vietnam. And despite throughout the world. For a brief the double-talk emanating from moment, when the Israeli army Washington, the rulers of the U.S. first swept into the Arab countries, were and are ready to escalate Washington felt it might have to their aggression into the Mideast intervene with its own forces. if need be. FLEE ISRAELI BLITZKRIEG. Arab refugees on road to Amman, Jordan, after crossing Jordan But the Israeli success achieved The assurance being shown on River. Reports indicate that more than 100,000 have fled Israeli aggression in western Jordan. Johnson's aim and - as a bonus - the Mideast by the Johnson admi while doing so left him looking nistration today is by no means By Barry Sheppard doctors from the American Uni ern diplomatic sources reported like a man of peace and modera what prevailed in the initial stage JUNE 14 - In a gloating pro versity Hospital in Beirut, which from Jordan said that in Jerusa tion. -

JEWS in the AMERICAN LABOR MOVEMENT: PAST, PRESENT and FUTURE by Bennett Muraskin

JEWS IN THE AMERICAN LABOR MOVEMENT: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE by Bennett Muraskin INTRODUCTION Think of the greatest strikes in US labor history. Apart from the garment workers' strikes in New York and Chicago before World War One, none come to mind in which Jews played a major role. The railroad workers' strike in 1877, the strikes for the eight-hour day in 1886, the Homestead Strike in 1892, the Pullman strike in 1894, the coalminers' strike in 1902, the steelworkers' strike in 1919, the general strike in San Francisco in 1934 and autoworkers' sit- down strike in 1936-1937 all occurred either before Jews immigrated to the US in large numbers or in industries where few Jews were employed. Among the “industrial proletariat” considered by Marxists to be the agency of social revolution, Jews were under-represented. Furthermore, apart from the WASP elite, only Jews, among all European immigrants to the US, have been over-represented in the world of business. But if you look a little closer, you will find Jews as the ferment for a great deal of radical labor activism. The only two Socialist Party candidates elected to the US Congress were Victor Berger and Meyer London. Bernie Sanders is the only US Senator to call himself a “socialist.” All three were Jews. (Ronald Dellums, a non-Jewish Black man who represented Berkeley CA in Congress as Democrat from 1970 to 1997, is the only other person to so identify.) The Jewish garment workers' unions pioneered social unionism and were among the founders of the CIO. -

AFT Office of the President Records

AFT - Office of the President Collection Papers, 1960-1974 (predominately 1968-1974) 22 linear feet Accession # 1553 DALNET # OCLC # In 1916, a handful of teachers met outside of Chicago to discuss the formation of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) . What brought them together was the belief that they needed a new national organization that would be committed to their professional interests, would benefit the people they served, and would work to create strong local unions affiliated with the American labor movement. From this foundation, the AFT has grown into a trade union representing workers in education, health care, and public service. The records of the AFT’s office of the President Collection consist of minutes, correspondence, reports, publications and other materials documenting the union’s activities in organizing and servicing affiliates, improving teaching conditions and influencing legislation affecting education and social issue during the presidencies of Charles Cogen and David Selden. Important subjects in the collection: Collective Bargaining - Education - United States Education - Bilingual Educational Change Education - Curricula Educational - Finance Education - Special Education Education - Law and Legislation Education and Crime National Education Association More Effective Schools Program Oceanhill-Brownsville Professional Employees-Labor Unions- United States Public Employee - Labor Unions - United States School Children - Transportation - United States Segregation in Education - United States Sexual - Discrimination 1 Schools - Discrimination Strikes and Lockouts - Teachers - United States Strikes and Lockouts - Newark - New Jersey Strikes and Lockouts - San Francisco - California Teachers - Job Stress Teachers - Los Angeles - California Teachers - New York City - New York Teachers - Political Activity Teachers - United States Teacher Centers Working Class - Education Important correspondents in the collection: Joseph Alioto Israel Kugler Si Beagle Harry V. -

The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at the Breman Museum Mss 167, Rubin and Lola Lansky Papers, 1940- 1996

William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History Weinberg Center for Holocaust Education THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES FOR SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY AT THE BREMAN MUSEUM MSS 167, RUBIN AND LOLA LANSKY PAPERS, 1940- 1996 BOX 1, FILE 7 Holocaust Conferences and Institutes, 1989-1990 ANY REPRODUCTION OF THIS MATERIAL WITHOUT THE EXPRESS WRITTEN CONSENT OF THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES IS STRICLY PROHIBITED The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum ● 1440 Spring Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30309 ● (678) 222-3700 ● thebreman.org \ I ' THE~ 9TH ANNUAL SCHOLARS' CON.FERENCE ON THE HOLOCAUST 11 8earing Witness: 1939-198911 5-7 March 1989 Holiday Inn: Independence Mall Philadelphia Alan L. Berger Chairman Franklin H. Littell Hubert G. Locke Co-Founders Sponsors The Anne Frank Institute of Philadelphia The United States Holocaust Memorial Council National Association of Holocaust Educators The International Bonhoeffer Society Cuba Family Archives Mss 167 Rubin and Lola Lansky Papers, 1940-1996, The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at the Breman Museum ). .. , .f ' International Boahoeffer Society carries on the memory and work of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-45), a young ecumenical leader who opposed Nazism and was martyred. His writ ings, like his Life and Death, have informed and inspired readers in many countries. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council is an agency of the Federal Government, with 55 members appointed to 5-year terms by the President by and with the consent of the Sen ate. In addition to holding annual Yorn Hashoah (Day of Remembrance) commemorations, the council is building a memorial museum on the mall in Washingto~. -

Institutions of Higher Education and Urban Problems: a Bibliography and Review for Planners

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 086 116 HE 005 024 AUTHOR Daly, Kenneth, Comp. TITLE Institutions of Higher Education and Urban Problems: A Bibliography and Review for Planners. Council of Planning Librarians Exchange Bibliography #398-399-400. INSTITUTION Council of Planning Librarians, Monticello, Ill. PUB DATE May 73 NOTE 261p. AVAILABLE FROM Council of Planning Librarians, Post Office Box 229, Monticello, Illinois 61856 ($12.50) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS *Bibliographies; City Problems; Community Colleges; Educational Administration; *Educational Planning; *Higher Education; Institutional Role; Literature Reviews; Planning; *School Community Relationship; *Urban Universities ABSTRACT The demand that institutions of higher education do something about the problems of the cities/generated a great deal of discussion during the 1960s. Unrest within the university and in the city provoked a number of programs and projects that attempted to bring the resources of the university to bear on different aspects of urban life, and even sometimes to make these resources available to city-dwellers. These activities stimulated further discussion and controversy. This bibliography is an attempt to bring together those contributions to this literature that might be useful for those who have to plan the role of the university in the city in the new content of the 1970s. The basic concern of the literature review section is to analyze what the different writers have to contribute to the self-understanding of planners of institutions and systems of higher education. The bibliography is divided into 6 parts: institutions of higher education; higher education in and for the city; university degree programs and the city; institutional activity in the'community; planning active institutions; and bibliographies and directories. -

Revolution Too Soon: Woman Suffragists and the Living Constitution, A

A REVOLUTION TOO SOON: WOMAN SUFFRAGISTS AND THE "LIVING CONSTITUTION" ADAM WINKLER* From 1869 to 1875, activists associatedwith the National Woman Suffrage Associa- tion, including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, argued that the United States Constitution guaranteed women's right to vote. Adam Winkler ar- gues that this movement-which the suffragists termed the "New Departure"-- rested on an innovative theory of constitutional interpretationthat would become the dominant mode of constitutionalconstruction in the twentieth century. Now recognizable as "living constitutionalism," the suffragists' approach to constitu- tional interpretation was harshly critical of originalism-the dominant mode of nineteenth-century interpretation-andproposed to construe textual language to keep up with changingsocietal needs. This Article analyzes the intellectual currents that made plausiblethe suffragists' embrace of an evolutionaryinterpretive method- ology, traces the development of the suffragists' approach as they fought for the franchise in Congress and in the courts, and reveals how radicalsuffragists encoun- tered the obstacles of originalism at every turn. Correcting the error of constitu- tional historians who assert that living constitutionalism first emerged in the Progressive Era, this Article stakes a claim for recognizing woman suffragists as important innovators at the forefront of modern constitutional thought. Introduction .................................................... 1457 I. Originalism and the Intellectual Currents Underlying Static Constitutionalism ................................. 1460 A. Originalism and the Turn to Evolutionary Constitutionalism in Historical Scholarship ......... 1460 B. The Institutional and Cultural Context of the Suffragists' Constitutional Method .................. 1466 II. The National Woman Suffrage Association and the Development of Suffragist Living Constitutionalism ....1473 A. A Minor Suggestion ................................ 1473 * Lecturer in Law, University of Southern California Law School; John M.