Thesis Designing the Hyphen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

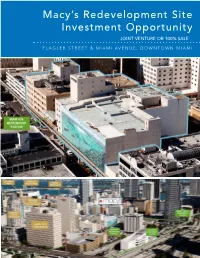

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Landscaping at the Water's Edge

LANDSCAPING/GARDENING/ECOLOGY No matter where you live in New Hampshire, the actions you take in your landscape can have far-reaching effects on water quality. Why? Because we are all connected to the water cycle and we all live in a watershed. A watershed is the LANDSCAPING land area that drains into a surface water body such as a lake, river, wetland or coastal estuary. at the Water’sAN ECOLOGICAL APPROACHEdge LANDSCAPING Landscaping at the Water’s Edge is a valuable resource for anyone concerned with the impact of his or her actions on the environment. This book brings together the collective expertise of many UNH Cooperative Extension specialists and educators and an independent landscape designer. Unlike many garden design books that are full of glitz and glamour but sorely lacking in substance, this affordable book addresses important ecological issues and empowers readers by giving an array of workable at the Water’s Edge solutions for real-world situations. ~Robin Sweetser, Concord Monitor columnist, garden writer for Old Farmer’s Almanac, and NH Home Magazine Landscaping at the Water’s Edge provides hands-on tools that teach us about positive change. It’s an excellent resource for the gardener, the professional landscaper, designer, and landscape architect—to learn how to better dovetail our landscapes with those of nature. ~Jon Batson, President, NH Landscape Association Pictured here are the : A major river watersheds in N ECOLOGICAL APPROACH New Hampshire. This guide explains how our landscaping choices impact surface and ground waters and demonstrates how, with simple observation, ecologically based design, and low impact maintenance practices, you can protect, and even improve, the quality of our water resources. -

Miami Office Space Can Be Found by Those Who Search February 7, 2017 By: Carla Vianna

Miami Office Space Can Be Found by Those Who Search February 7, 2017 By: Carla Vianna Businesses searching for space in Miami's urban core have more options than they might think. While vacancy rates are down across the board, significant chunks of space are available in several Class A buildings in downtown and the Brickell Avenue financial district. "There are more alternatives available for those companies that take the time to appropriately investigate the market," said Chris Lovell, a senior managing director with Savills Studley in Miami. Leasing space on an upper floor with a view may be difficult since only six buildings on Brickell have a full floor above the 20th story available for lease. For tenants that can live without the view, there is plenty of open space to choose from. Four downtown Class A buildings have at least 75,000 square feet of contiguous space available, one Class A building on Brickell has a 65,000- square-foot block — "and we don't have tenants of that size standing in line to the claim the space," Lovell said. Savills Studley has found many of the large available blocks are in older downtown buildings. "You're always going to have buildings that are going to have certain pockets available," said Tere Blanca, founder of Miami-based Blanca Commercial Real Estate Inc. She said the market is responding well to the new Miami Central project, which is under construction with 60 percent of its office component pre- leased. The mixed-use development will serve as Brightline's downtown train station and will add 286,000 square feet of office space in two buildings. -

Sustainable Landscaping Reading List

Sustainable Landscaping General Garden Revolu-on: How Our Landscapes Can Be A Source Of Environmental Change by Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher Plan-ng In A Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communi-es For Resilient Landscapes by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West The Weather-Resilient Garden: A Defensive Approach To Planning & Landscaping by Charles W. G. Smith and Elayne Sears, Bobbi Angell Planng for Water Conservaon The Water-Saving Garden: how to grow a gorgeous garden with a lot less water by Pam Penick Gardening With Less Water: Low-Tech, Low-Cost Techniques : Use Up To 90% Less Water In Your Garden by David Bainbridge Greywater Greywater, Green Landscape: How To Install Simple Water-Saving Irriga-on Systems In Your Yard by Laura Allen The New Create An Oasis With Greywater: Integrated Design For Water Conserva-on : Reuse, Rainwater Harves-ng & Sustainable Landscaping by Art Ludwig The Water-Wise Home: How To Conserve, Capture, And Reuse Water In Your Home And Landscape by Laura Allen Permaculture The Permaculture Earthworks Handbook: How To Design And Build Swales, Dams, Ponds, And Other Water Harves-ng Systems by Douglas Barnes Permaculture Guide To Reed Beds: Designing, Building And Plan-ng Your Treatment Wetland System by Féidhlim Harty The Resilient Farm And Homestead: An Innova-ve Permaculture And Whole Systems Design Approach by Ben Falk and Cornelius Murphy Edible Landscaping Foodscaping: Prac-cal And Innova-ve Ways To Create An Edible Landscape by Charlie Nardozzi Edible Landscaping With A Permaculture Twist: How To Have Your Yard And Eat It Too by Michael Judd Green Roof Green Roofs In Sustainable Landscape Design by Steven L. -

OFFERING MEMORANDUM Miami, FL 33131 235 SE 1St Street Themiamiplaza.Com

THE P LA ZA themiamiplaza.com MEMORANDUM 235 SE 1st Street Miami, FL 33131 OFFERING THE P LA ZA THE P LA ZA 235 SE 1st Street THE OFFERING Miami, FL 33131 he Plaza is a 81,000 SF office building Ton a 20,000 SF corner lot located in the heart of Downtown Miami and its most prominent corner. The site benefits from the most liberal mixed-use zoning in all of South Florida, T6-80-O, allowing up to 489,600 SF of development and 470 residential units. The Plaza is an amazing add value office building with tremendous future uses for development. Developers will benefit from the ability to receive temporary cash flow while waiting on the next cycle or plan approval. THE CORNER OF DOWNTOWN MIAMI THE P LA ZA PROPERTY SUMMARY + + Address: Lot Size: Building Size: Zoning: FLR Allowable FLR Allowable +Bonus Building Height: Building Height +Bonus: Allowable Units: Folio: 235 SE 1st St. 20,400/ 81,382 SF T6-80-O 489,600 SF Unlimited 80 Unlimited 470 01-0112-000-1020 Miami, FL 33131 0.47 Acres 6 7 FOUR SEASONS BRICKELL CITY INVESTMENT CENTRE ICON BRICKELL HIGHLIGHTS SOUTHEAST FINANCIAL CENTER WELLS FARGO CENTER MIAMI TOWER ASTON MARTIN JAMES L. KNIGHT RESIDENCES CENTER MET SQUARE CINEPLEX WHOLE FOODS CENTRO Covered Land with In-Place Income he Plaza is a prime opportunity to repurpose or add value to an existing Tclass C office building located in Downtown’s most highly trafficked corridor. The property is positioned to capture an already active-large tenant base with over 175,000 employees existing within Downtown’s LA EPOCA Central Business District. -

Viscontis Signature Cocktails -Visconti’S Classics

Viscontis Signature Cocktails -Visconti’s Classics- Visconti’s Old Fashioned - Booker’s small batch bourbon, simple syrup, dash Reagan bitters, lemon & orange slice, luxardo cherry, splash soda Old World Manhattan- Woodford Rye Whiskey, Antica sweet vermouth, regans orange bitters, garnished with a luxardo cherry Perfect Manhattan - Knob Creek bourbon, a splash of Antica sweet and Cinzano dry vermouth, orange bitters, served up with a luxardo cherry Basil Ginger Manhattan – Basil Hayden bourbon, Domaine de Canton ginger liqueur, Antica sweet vermouth, basil leaf garnish Vieux Carre`- High West Double Rye whiskey, Remey VSOP Cognac, Antica sweet vermouth, dash Benedictine, dash peychaud’s & angostura bitters, lemon twist Sazerac – High West Double Rye whiskey, dash simple syrup and bitters, served chilled in a rocks glass lined with St. Germain Absinthe, lemon twist garnish Classic Sidecar – Courvoisier cognac, Cointreau orange liqueur, fresh lemon juice, served up with a sugar rim and lemon twist -Italian Inspired- Visconti’s Negroni - Equal parts Hendricks gin, Antica sweet vermouth & Campari, served with orange twist Limoncello Martini – Capri Natura limoncello, Ketel One vodka, and fresh-squeezed lemon juice Palermo Cosmopolitan – Kettle One Oranje vodka, Patrón Citrónge, fresh squeeze lime and cranberry juice Visconti’s Sicilian Kiss - Maker’s Mark bourbon, amaretto and DeKuyper Peachtree peach schnapps served in a martini glass Italian Stallion - Maker’s Mark bourbon, Campari and Antica sweet vermouth Sicilian Screwdriver – Kettle -

Miami Cbd Large Blocks of Office Space

RESEARCH MIAMI CBD AUGUST 2019 LARGE BLOCKS OF OFFICE SPACE 836 MACARTHUR CAUSEWAY 100,000+ SF Blocks 395 Southeast Financial Center Four Seasons Tower 200 S Biscayne Boulevard 1441 Brickell Avenue Ponte Gadea USA 9 Millennium Partners Management 1 1,225,000 RBA – 67.8% Leased 258,767 RBA – 98.1% Leased 133,120 SF Max Contig. 28,763 SF Max Contig. $53.25/RSF FS $60.00/RSF FS Citigroup Center 1221 Brickell 201 S Biscayne Boulevard 1221 Brickell Avenue Crocker Partners Rockpoint Group 2 809,594 RBA – 74.0% Leased 10 408,649 RBA – 86.1% Leased 95 127,634 SF Max Contig. 26,761 SF Max Contig. $48.00-$52.00/RSF FS $52.50/RSF FS Freedom PORT BLVD A1A Tower Wells Fargo Center 50,000 - 99,999 SF Blocks 333 SE 2nd Avenue AVE MetLife Real Estate Investments AVE 11 ND 752,845 RBA – 85.9% Leased ND SunTrust International Center 26,000 SF Max Contig. 1 SE 3rd Avenue BISCAYNE BLVD BISCAYNE $48.00/RSF FS N MIAMI AVE MIAMI N 2 NE NW 2 NW MiaMarina Pacific Coast Capital Partners MIAMI RIVER 3 440,299 RBA – 66.4% Leased 90,255 SF Max Contig. $38.00-$40.00/RSF FS 15,000 - 24,999 SF Blocks Brickell Office Plaza Brickell World Plaza Downtown 777 Brickell Avenue 600 Brickell Avenue 8 Padua Realty Company Elm Spring, Inc. 4 288,457 RBA – 74.8% Leased 12 631,866 RBA – 92.5% Leased 3 6 68,386 SF Max Contig. CLASS 24,138 SF Max Contig. -

Foodscape Knox

Written By: Caroline Conley Advisor: Tom Graves Company Description Market and Industry Analysis Company Structure FoodScape Knox is an edible landscaping Political Economic Social Technological Operations Strategy: - Attention on social -Consumer spending -Increase in health and -Increase in Social 1. Initial Contact service and social enterprise located in justice and income increase 3.8% in 4th fitness initiatives Media Usage 2. Consultation and Design inequality quarter 2017 -Increase in social -E-technology and 3. Installation Knoxville, TN. Our target market is the 4. Follow Up Visit - Decrease in - Following Recession, consciousness vertical farming. health conscious middle upper class of 5. Maintenance (Optional) government consumers have not -Increased interest in -Factory Farming Knox county. For every landscape installed, sustainability efforts ceased to continue in food production and techniques another landscape is implemented in a low - Increase in industry the thrifty habits unification of gardeners and grassroots developed during the via social media income neighborhood within Knoxville. sustainability economic downturn -Celebrities are initiatives growing organic The uniqueness of our service combined with the effort towards community development will act as the primary Key Visuals competitive advantage. In the long run, FoodScape Knox will start offering edible Visuals for Landscape designs utilizing Critical Success Factors: landscaping services to businesses and permaculture methodology. Excellent Design- Landscapes -

53408-Legendary-Bacardi-Cocktails

HELVETICA BOLD 14 PT SIZE HELVETICA BOLD 12 PT. SIZE Helvetica regulat 12 pt. size As tastes evolve and new trends take over, cocktails come and go. However, BACARDI® Legendary Cocktails have been enjoyed for more than 100 years ─ each with its own unique story. Read on to discover the rich history behind these treasured recipes and learn the true legacy of the famous BACARDI rum brand and its timeless connection to many of the world’s favorite cocktails including the Original BACARDI Cuba Libre, the Original BACARDI Daiquirí, the Authentic BACARDI Mojito, the BACARDI Piña Colada and El Presidente BACARDI. 1 HELVETICAORIGINAL BACARDI BOLD 14® CUBA PT SIZE LIBRE HELVETICAThough the Original BOLD 12BACARDI PT. SIZE Cuba Libre is one of the most popular cocktails in the Helveticaworld, it is regulatalso one 12 of pt. the size drinks least known by its proper name. More commonly called “BACARDI and Coke™,” the Cuba Libre was created during the Cuban liberation in 1900 and has a very significant story attached to its authentic title. The Spanish-American war ended on July 17, 1898 at the Battle of San Juan Hill, famously fought with the assistance of future United States President Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders. Roosevelt and his men stayed on in Cuba to ensure that political life resumed peacefully in the new nation. Roosevelt’s commander, General Leonard Wood was appointed the Military Governor of Santiago de Cuba. Shortly after the war, with military intervention still in effect, two Americans opened The American Bar on Neptuno Street in Havana. -

Vice 300 Biscayne Boulevard

DOWNTOWN MIAMI FL VICE 300 BISCAYNE BOULEVARD CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR West block of Biscayne Boulevard between NE 3rd and NE 4th Streets NE 4TH STREET 38 FT SPACE Ground Floor 1,082 SF FRONTAGE 38 FT on NE 4th Street 1,082 SF TERM Negotiable (COMING SOON) POSSESION LEASE OUT Summer 2018 SITE STATUS New construction LEASE OUT CO-TENANTS Caffe Fiorino (coming soon), GOGO Fresh Foods (coming soon) and OXXO Care Cleaners (coming soon) NEIGHBORS Area 31, Fratelli Milano, CVI.CHE 105, Gap, Il Gabbiano, Juan Valdez Coffee, NIU Kitchen, Pollos & Jarras, Segafredo, Skechers, Starbucks, STK Miami, Subway, Ten Fruits, Toro Toro, Tuyo Restaurant, Victoria’s Secret, Wolfgang’s Steakhouse and Zuma COMMENTS VICE is a 464-unit apartment tower under construction in the heart of Downtown Miami Directly across from Bayside Marketplace and neighboring Miami Dade College, two blocks from American Airlines Arena, and adjacent to the College-Bayside Metromover Station Miami-Dade College has over 25,000 students on campus daily (COMING SOON) (COMING SOON) ADDITIONAL RENDERINGS CONCEPTUAL RENDERING CONCEPTUAL RENDERING CONCEPTUAL RENDERING Downtown Miami & Brickell Miami, FL AREASeptember 2017 RETAIL NW 8TH STREET NE 8TH STREET VICE AVENUE 300 BISCAYNE NE 7TH STREET NE 2ND HEAT BOULEVARD BOULEVARD MIAMI FL FREEDOM TOWER NW 6TH STREET PORT BOULEVARD MIAMI-DADE COLLEGE FACULTY Downtown Miami PARKING Movers NW 5TH STREET NE 5TH STREET 300 BISCAYNE BOULEVARDP MIAMI-DADE COLLEGE FEDERAL NE 4TH STREET NE -

Fish Bowls Classic Cocktails

Fish Bowls (Wednesday Night ½ Price) SOUR PATCH 32 RED SANGRIA 32 Smirnoff Raspberry Vodka, Bacardi Límon Rum, St. Germain Smirnoff Cherry Vodka, sour Elderflower Liqueur, sour mix, apple lemon-lime soda orange juice, house merlot OTTER POP 32 STRAWBERRY MARGARITA 32 Smirnoff Raspberry Vodka, Cazadores Blanco Tequila, Agave, DeKuyper Blue Curaçao, sweet Strawberry liqueur, sweet n sour, lime juice ‘n sour, and lemon-lime soda SHARK BITE 32 TROPICAL PARADISE 32 Cazadores Blanco Tequila, Bacardi Malibu Coconut Rum, Cîroc Peach O Rum, Bacardi 151 Rum, pineapple Vodka, pineapple juice, cranberry juice, orange juice, sweet ‘n sour PURPLE RAIN 32 JUNGLE JUICE 32 Ketel One Vodka, Peachtree Ketel One Vodka, Bacardi O Rum, Schnapps, Dekuyper Razzmatazz Bacardi Superior White Rum, Liqueur, sweet ‘n sour, pineapple pineapple juice, orange juice PEACH BLOSSOM 32 TOKYO MOJITO 32 Cîroc Peach Vodka, Hendrick’s Myers’s Platinum Rum, Gin, Bacardi Superior White fresh mint, agave, lime Rum, Cazadores Blanco Tequila, agave, peach puree Classic Cocktails SKINNY MARGARITA 11 MOSCOW MULE 11 Cazadores blanco, agave nectar, fresh lime juice Ketel One Vodka, lime juice, ginger beer JALAPENO MARGARITA 11 DARK ‘N STORMY 11 Cazadores Blanco, Triple sec, muddled fresh Dark Myers Rum, ginger beer jalapenos GINGERITA 13 TAI CHI 13 Don Julio Blanco Tequila, swee sour, lime juice, Malibu Rum, Captian Morgan Rum, Pineapple ginger liqueur juice,other tropical flavors, topped with Bacardi 151 BLOODY MARY 10 Kettle One Vodka, Shirasoni Bloody Mary Mix, ADIOS TEA 13 spicy, olive Malibu rum, Tanqueray, Cazadores Tequila, Ketal One, Blue Curacao, Grenadine MAI TAI 11 Barcardi Rum, Fresh lime juice, Orange curaçao, Orgeat syrup, Dark Myers Rum POMEGRANATE MOJITO 10 Don Q, Pomegranate, muddled fresh mints, lime juice . -

Curbing Land Degradation Through Sustainable Landscaping and Building Resilient Cities

IIARD International Journal of Geography and Environmental Management E-ISSN 2505-8821 P-ISSN 2695-1886, Vol 6. No. 2 2020 www.iiardpub.org Curbing Land Degradation through Sustainable Landscaping and Building Resilient Cities. Emmamoge Orewere1, Bilkisu Hassan2, Mustapha Faiza2 Ayodele Owonubi (Ph.D)1, and Michael Olabode Ogunrayewa (Ph.D)3 1Department of Horticulture and Landscape Technology, Federal College of Forestry, Jos. 2 Department of Architecture, College of Environmental Studies, Kaduna Polytechnic. 3 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, University of Jos, Plateau State. [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nation particularly sustainable cities and communities development (goal eleven) and life on land (goal fifteen) targeted for year 2030 and Nigeria’s Vision 20:2020 (NV 20:2020) Economic Transformation Blueprint cannot be overemphasized. Land degradation will remain an important global issue for the 21st century because of its adverse impact on agronomic productivity, the environment, and its effect on food security and the quality of life. Land degradation is induced by human and natural activities. This paper focuses on the human induced land degradation as they can be prevented. This includes mining activities, erosion, bush burning, and loss of agricultural land among others. The productivity of some lands has declined by 50% due to soil erosion and desertification. Landscaping as an emerging field seeks to enhance and curb land degradation to certain aspects within cities and Nigeria in general. It focuses on Jos, the capital of Plateau State situated in the North-Central geopolitical zone of Nigeria. The methodology employed for this study is physical site survey, case study and review of related literature.