Schoodic Peninsula Historic District Other Name: N/A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Island Explorer Short Range Transit Plan

Island Explorer Short Range Transit Plan FINAL REPORT Prepared for the National Park Service and the Maine Department of Transportation May 21, 2007 ISLAND EXPLORER SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction and Summary 1.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________ 1-1 1.3 Summary of Key findings________________________________________________________________ 1-3 Chapter 2: Review of Previous Studies 2.1 Phase 2 Report: Seasonal Public Transportation on MDI (1997) _________________________________ 2-1 2.2 Visitor Center and Transportation Facility Needs (2002) ________________________________________ 2-2 2.3 Intermodal Transportation Hub Charrette (2002) ______________________________________________ 2-2 2.4 Year-round Transit Plan for Mount Desert island (2003) ________________________________________ 2-3 2.5 Bangor-Trenton Transportation Alternatives Study (2004)_______________________________________ 2-3 2.6 Visitor Use Management Strategy for Acadia National Park (2003) _______________________________ 2-7 2.7 Visitor Capacity Charrette for Acadia National Park (2002)______________________________________ 2-9 2.8 Acadia National Park Visitor Census Reports (2002-2003) _____________________________________ 2-10 2.9 MDI Tomorrow Commu8nity Survey (2004) _______________________________________________ 2-12 2.10 Strategic Management Plan: Route 3 corridor and Trenton Village (2005) ________________________ 2-13 Chapter 3: Onboard Surveys of Island Explorer Passengers -

Beaver Log Explore Acadia Checklist Island Explorer Bus See the Ocean and Forest from the Top of a Schedule Inside! Mountain

National Park Service Acadia National Park U.S. Department of the Kids Interior Acadia Beaver Log Explore Acadia Checklist Island Explorer Bus See the ocean and forest from the top of a Schedule Inside! mountain. Listen to a bubbly waterfall or stream. Examine a beaver lodge and dam. Hear the ocean waves crash into the shore. Smell a balsam fir tree. Camping & Picnicking Acadia's Partners Seasonal camping is provided within the park on Chat with a park ranger. Eastern National Bookstore Mount Desert Island. Blackwoods Campground is Eastern National is a non-profit partner which Watch the stars or look for moonlight located 5 miles south of Bar Harbor and Seawall provides educational materials such as books, shining on the sea. Campground is located 5 miles south of Southwest maps, videos, and posters at the Hulls Cove Visitor Hear the night sounds of insects, owls, Harbor. Private campgrounds are also found Center, the Sieur de Monts Nature Center, and the and coyote. throughout the island. Blackwoods Campground park campgrounds. Members earn discounts while often fills months in advance. Once at the park, Feel the sand and sea with your bare feet. supporting research and education in the park. For all sites are first come, first served. Reservations information visit: www.easternnational.org 2012 Observe and learn about these plants and in advance are highly recommended. Before you animals living in the park: arrive, visit www.recreation.gov Friends of Acadia bat beaver blueberry bush Friends of Acadia is an independent nonprofit Welcome to Acadia! cattail coyote deer Campground Fees & organization dedicated to ensuring the long-term Going Green in Acadia! National Parks play an important role in dragonfly frog fox Reservations protection of the natural and cultural resources Fare-free Island Explorer shuttle buses begin helping Americans shape a healthy lifestyle. -

Intelligent Transportation in Acadia National Park

INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION IN ACADIA NATIONAL PARK Determining the feasibility of smart systems to reduce traffic congestion An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Angela Calvi Colin Maki Mingqi Shuai Jackson Peters Daniel Wivagg Date: July 28, 2017 Approved: ______________________________________ Professor Frederick Bianchi, Advisor This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students. Submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. i Abstract The goal of this project was to assess the feasibility of implementing an intelligent transportation system (ITS) in Acadia National Park. To this end, the features of an ITS were researched and discussed. The components of Acadia’s previous ITS were recorded and their effects evaluated. New technologies to implement, replace, or upgrade the existing ITS were researched and the companies providing these technologies were contacted and questioned for specifications regarding their devices. From this research, three sensor systems were identified as possibilities. These sensors were magnetometers, induction loops, and cameras. Furthermore, three methods of information dissemination were identified as useful to travelers. Those methods were dynamic message signs, websites, and mobile applications. The logistics of implementing these systems were researched and documented. A cost analysis was created for each system. The TELOS model of feasibility was then used to compare the strengths of each sensor in five categories: Technical, Economic, Legal, Operational and Schedule. Based on the results of the TELOS and cost analyses, the sensors were ranked in terms of feasibility; magnetometers were found to be the most feasible, followed by induction loop sensors and then camera-based systems. -

Sculpture Symposium SESSION I Message from the Maine Arts Commission

Sculpture Symposium SESSION I Message from the Maine Arts Commission Dear Friends, As we approach the second round of the Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium, I am struck by the wondrous manifestation of a seedling idea—how the expertise and enthusiasm of a few can energize a community beyond anything in recent memory. This project represents the fruits of the creative economy initiative in the most positive and startling way. Schoodic Peninsula, Maine Discussions for the Symposium began in 2005 around a table at the Schoodic section of Acadia National Contents Park. All the right aspects were aligned and the project was grass roots and supported by local residents. It Sculptors used indigenous granite; insisted on artistic excellence; and broadened the intelligence and significance of the project through international inclusion. The project included a core educational component and welcomed Dominika Griesgraber, Poland 4 tourism through on-site visits to view the artists at work. It placed the work permanently in surrounding communities as a marker of local support and appreciation for monumental public art. You will find no war Jo Kley, Germany 6 memorials among the group, no men on horseback. The acceptance by the participating communities of less literal and adventurous works of art is a tribute to the early and continual inclusion of resident involvement. Don Justin Meserve, Maine 8 It also emphasizes that this project is about beauty, not reverie for the past but a beacon toward a rejuvenated future. Ian Newbery, Sweden 10 The Symposium is a tour de force, an unparalleled success, and I congratulate the core group and all the Roy Patterson, Maine 12 surrounding communities for embracing the concept of public art. -

Schoodic Peninsula He Schoodic Peninsula, Narrow Gravel Road

National Park Service Acadia U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Schoodic Peninsula he Schoodic Peninsula, narrow gravel road. Although you can is located on the right, one-half mile containing the only section of drive up the one-mile road, you may down the road. Park here to access the TAcadia National Park on the also choose to walk one of the three Alder and Anvil Trails. The level and mainland, boasts granite headlands hiking trails that lead to the top. On easy Alder Trail begins across the road that bear erosional scars of storm a clear day from the summit, views from the entrance to the parking area. waves and flood tides. Although of the ocean, forests, and mountains The Anvil Trail, which leads to the similar in scenic splendor to portions claim your attention. 180-foot summit of the Anvil, begins of Mount Desert Island, the Schoodic several hundred yards down the road coast is more secluded. Returning to the main road, keep and around a curve. Both trails are right at the next intersection to reach marked with cedar posts. It is approximately a one-hour drive Schoodic Point. You will pass the from Hulls Cove Visitor Center entrance to the Schoodic Education Approximately two miles from the to the Schoodic Peninsula. In the and Research Center. The center, Blueberry Hill Parking Area, the park summer the Schoodic Peninsula is located on the site of a former U.S. ends at Wonsqueak Harbor. Two miles accessible via ferry service from Bar Navy base, promotes park science beyond the park is the village of Birch Harbor to Winter Harbor, and the and education activities and related Harbor and the intersection with Island Explorer bus service provides regional, national, and international Route 186. -

Schoodic Outdoors Brochure

Schoodic National Scenic Byway! Scenic National Schoodic 5 GREAT FRENCHMAN BAY CONSERVANCY ACADIA NATIONAL PARK hiking, biking and paddling on the on paddling and biking hiking, PLACES TO Discover the special places for for places special the Discover HANG OUT The Conservancy has built and maintains a system of trails Corea Heath: Access from Route 1 to West Bay Rd/Route The Schoodic District of Acadia National Park offers 7 miles of Tidal Falls Preserve: At this narrow opening between Taunton 186, then left on Route 195/Corea Rd to parking. The wooded hiking trails, plus hiking on 8.5 miles of off-road biking paths. SCENIC BYWAY SCENIC for public use—look for the blue blazes! Call 207-422-2328 or Bay and the ocean, the water races in and out with the tides visit frenchmanbay.org loop trail provides overlooks of the bog and beaver dams, These trails link the ocean shore to the mountains, and offer SCHOODIC NATIONAL NATIONAL SCHOODIC creating a “reversing falls” (suitable for paddling by experts only). lodges and tranquil water flows. Great bird watching. Trail Tucker Mountain: Access from Route 1 from informal a variety of hiking experiences. WELCOME TO THE THE TO WELCOME HikingHiking Headquarters for Frenchman Bay Conservancy, it is a great place parking on the old Route 1 road bed across and slightly to the length: 1.25-mile loop. The Corea Heath Division of the Photo courtesy of Frenchman Bay Conservancy Bay of Frenchman courtesy Photo for picnicking and wildlife viewing. National Wildlife Refuge is just south of the Corea Heath Photo courtesy of Larry Peterson Larry of courtesy Photo east of the Long Cove rest area. -

Wabanaki Textiles, Clothing, and Costume. Bruce J. Bourque and Laureen A

Uncommon Threads: Wabanaki Textiles, Clothing, and Costume. Bruce J. Bourque and Laureen A. LaBar. Augusta, ME: Maine State Museum with the University of Washington Press, 2009. 192 pp.* Reviewed by Rhonda S. Fair In May of 2009, the Maine State Museum launched an exhibit of 100 Wabanaki objects; Bruce Bourque and Laureen LaBar curated the exhibit and wrote the companion book, Uncommon Threads: Wabanaki Textiles, Clothing, and Costume. Much more than a catalog of the objects on display, this book provides an examination of the history, art, and culture of the Maritime Peninsula’s indigenous population. After a very brief introduction, Bourque and LaBar divide their subject matter into four chapters, the first of which provides an overview of the Native peoples of the Maritime Peninsula. Though related to other Algonquian-speaking tribes along the eastern seaboard, the Wabanaki differed in some significant ways. For instance, the Wabanaki groups did not practice agriculture based on corn, beans, and squash, preferring instead to hunt and gather a significant portion of their diet. As did other Native peoples on the coast, they had early contact with Europeans, first with fishermen and fur traders, and later, with colonists and soldiers. Also like their neighbors, the Iroquois, the Wabanki formed a coalition of affiliated tribal groups. Frank Speck described this as the Wabanaki Confederacy. He observed that the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Micmac had an identifiable national identity and met in common to discuss matters that would impact the confederacy as a whole. Agreements by the confederacy were documented not by written words, but with woven shell beads, or wampum. -

People of the Dawnland and the Enduring Pursuit of a Native Atlantic World

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MATTHEW R. BAHAR Norman, Oklahoma 2012 “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. Joshua A. Piker, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Catherine E. Kelly ______________________________ Dr. James S. Hart, Jr. ______________________________ Dr. Gary C. Anderson ______________________________ Dr. Karl H. Offen © Copyright by MATTHEW R. BAHAR 2012 All Rights Reserved. For Allison Acknowledgements Crafting this dissertation, like the overall experience of graduate school, occasionally left me adrift at sea. At other times it saw me stuck in the doldrums. Periodically I was tossed around by tempestuous waves. But two beacons always pointed me to quiet harbors where I gained valuable insights, developed new perspectives, and acquired new momentum. My advisor and mentor, Josh Piker, has been incredibly generous with his time, ideas, advice, and encouragement. His constructive critique of my thoughts, methodology, and writing (I never realized I was prone to so many split infinitives and unclear antecedents) was a tremendous help to a graduate student beginning his career. In more ways than he probably knows, he remains for me an exemplar of the professional historian I hope to become. And as a barbecue connoisseur, he is particularly worthy of deference and emulation. -

Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment Cover Illustration

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Maine Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment Cover Illustration: Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900) Schoodic Peninsula from Mount Desert at Sunrise, 1850–1855 Oil on paperboard 229 x 349 mm (9 x 13 3/4 in) Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Louis P. Church, 1917-4-332 Photo: Matt Flynn Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment Acadia National Park, Maine National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior April 2006 Contents Introduction 1 Glossary 29 Foundation for the Plan 2 Bibliography 31 Background 2 Purpose and Need for the Plan 2 Park Setting 3 Appendices Natural Resources 4 Appendix A: Concept for the Schoodic Education Cultural Resources 5 and Research Center 32 Park Facilities 8 Appendix B: Record of Decision 34 Visitor Experience 9 Appendix C: Section 106 Consultation Park Mission, Purpose, and Signifi cance 11 Requirements for Planned Undertakings 40 Legislative History 12 Appendix D: Proposed Navy Base Building Planning Issues 13 Reuse 41 Management Goals 14 Appendix E: Design Guidelines for Schoodic Education and Research Center 42 Appendix F: Alternative Transportation Assessment The Plan 17 Summary 44 Overview 17 Management Zoning 17 Management Prescriptions 20 List of Figures Resource Management 20 Figure 1: Acadia National Park Visitor Use and Interpretation 21 Figure 2: Schoodic Peninsula and Surrounding Cooperative Efforts and Partnerships 26 Islands Operational Effi ciency 26 Figure 3: Existing Features – Schoodic District Figure 4: Existing Features – Former Navy Base Figure 5: Schoodic Management Zoning List of Contributors 28 Figure 6: Proposed Navy Base Building Reuse Little Moose Island Introduction The National Park Service acquired property prescriptions. -

A STORY of the WASHINGTON COUNTY UNORGANIZED TERRITORIES Prepared by John Dudley for Washington County Council of Governments March 2017

A STORY OF THE WASHINGTON COUNTY UNORGANIZED TERRITORIES Prepared by John Dudley for Washington County Council of Governments March 2017 The story of the past of any place or people is a history, but this story is so brief and incomplete, I gave the title of “A Story”. Another person could have written quite a different story based on other facts. This story is based on facts collected from various sources and arranged in three ways. Scattered through one will find pictures, mostly old and mostly found in the Alexander- Crawford Historical Society files or with my families’ files. Following this introduction is a series on pictures taken by my great-grandfather, John McAdam Murchie. Next we have a text describing the past by subject. Those subjects are listed at the beginning of that section. The third section is a story told by place. The story of each of the places (32 townships, 3 plantations and a couple of organized towns) is told briefly, but separately. These stories are mostly in phrases and in chronological order. The listed landowners are very incomplete and meant only to give names to the larger picture of ownership from 1783. Maps supplement the stories. This paper is a work in progress and likely never will be complete. I have learned much through the research and writing of this story. I know that some errors must have found their way onto these pages and they are my errors. I know that this story is very incomplete. I hope correction and additions will be made. This is not my story, it is our story and I have made my words available now so they may be used in the Prospective Planning process. -

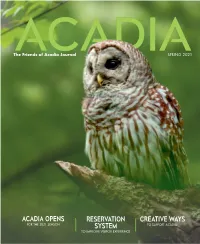

Spring 2021 Spring Creative Ways Ways Creative

ACADIA 43 Cottage Street, PO Box 45 Bar Harbor, ME 04609 SPRING 2021 Volume 26 No. 2 SPRING 2021 Volume The Friends of Acadia Journal SPRING 2021 MISSION Friends of Acadia preserves, protects, and promotes stewardship of the outstanding natural beauty, ecological vitality, and distinctive cultural resources of Acadia National Park and surrounding communities for the inspiration and enjoyment of current and future generations. VISITORS enjoy a game of cribbage while watching the sunset from Beech Mountain. ACADIA OPENS RESERVATION CREATIVE WAYS FOR THE 2021 SEASON SYSTEM TO SUPPORT ACADIA TO IMPROVE VISITOR EXPERIENCE ASHLEY L. CONTI/FOA friendsofacadia.org | 43 Cottage Street | PO Box 45 | Bar Harbor, ME | 04609 | 207-288-3340 | 800 - 625- 0321 PURCHASE YOUR PARK PASS! Whether walking, bicycling, riding the Island Explorer, or driving through the park, we all must obtain a park pass. Eighty percent of all fees paid in Acadia National Park stay in Acadia, to be used for projects that directly benefit park visitors and resources. BUY A PASS ONLINE AND PRINT Acadia National Park passes are available online: before you arrive at the park. This www.recreation.gov/sitepass/74271 allows you to drive directly to a Annual park passes are also available at trailhead/parking area & display certain Acadia-area town offices and local your pass from your vehicle. chambers of commerce. Visit www.nps.gov/acad/planyourvisit/fees.htm IN THIS ISSUE 10 8 12 20 18 FEATURES 6 REMEMBERING DIANNA EMORY Our Friend, Conservationist, and Defender of Acadia By David -

SIFTING THROUGH the BACKDIRT Vol

SIFTING THROUGH THE BACKDIRT Vol. 1, Issue 1 December, 2019 An occasional newsletter covering topics relating to archaeology in New Brunswick and the Maritimes From the President’s Desk Hello, Bonjour, Qey, Kwe’, and welcome to the inaugural issue of Sifting Through the Backdirt—an occasional newsletter discussing salient news and topics relating to archaeology and heritage in New Brunswick and the greater Maritime Peninsula. The intent of the newsletter is to provide our members and other In this issue: interested parties with a regular source of news summarizing the activities of the Association, its membership, and the greater archaeological and heritage • From the President’s Desk 1 community. The contents of each issue will vary and include such things as • News From the Board 1 updates from the Board of Directors, notifications regarding recent publications • In the Community 2 and conference presentations from our members, articles by guest contributors, • APANB in the News 2 Q&A’s with academics and professionals in archaeology and other related fields, • Speaker Series 3 and updates from the field. If you are interested in contributing to future volumes, • Upcoming Events 4 please send an email to the Board of Directors with your ideas. • Recent Contributions 4 • T-shirts are here! 4 Thanks | Merci | Woliwon | Wela’lin • Unionizing CRM Archaeology 5 Trevor Dow • Backdirt by the Numbers 6-8 President/Co-Editor News from the Board On November 9th, 2019 the Association held its Fall General Meeting in Moncton, where a new Board of Directors was nominated for the 2020-2022 term. Your new Board of Directors consists of: President— Trevor Dow Treasurer—Darcy Dignam Vice President—Gabe Hrynick Board Member—Ken Holyoke Secretary—Sara Beanlands Board Member—Vacant We look forward to working with you over the next two years to advance the objectives of the Association.