1960S British Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Film Journalism

Good of its kind? British film journalism HALL, Sheldon <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0950-7310> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/12366/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version HALL, Sheldon (2017). Good of its kind? British film journalism. In: HUNTER, Ian Q., PORTER, Laraine and SMITH, Justin, (eds.) The Routledge History of British Cinema. London, Routledge, 271-281. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk GOOD OF ITS KIND? BRITISH FILM JOURNALISM Sheldon Hall In his introduction to the 1986 collection All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema, Charles Barr noted that successive phases in the history of minority film culture in the UK have been signposted by the appearance of a series of small-circulation journals, each of which in turn represented “the ‘leading edge’ or growth point of film criticism in Britain” (5). These journals were, in order of their appearance: Close-Up, first published in 1927; Cinema Quarterly (1932) and its direct successors World Film News (1936) and Documentary News Letter (1940), all linked to the documentary movement; Sequence (1947); Sight and Sound (1949, the date when the longstanding BFI house journal’s editorship was assumed by Sequence alumnus Gavin Lambert); Movie (1962); and Screen (1971, again the date of a change in editorial direction rather than a first issue as such). -

JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE and BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release February 1994 JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994 A film retrospective of the legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau, spanning her remarkable forty-five year career, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on February 25, 1994. JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND traces the actress's steady rise from the French cinema of the 1950s and international renown as muse and icon of the New Wave movement to the present. On view through March 18, the exhibition shows Moreau to be one of the few performing artists who both epitomize and transcend their eras by the originality of their work. The retrospective comprises thirty films, including three that Moreau directed. Two films in the series are United States premieres: The Old Woman Mho Wades in the Sea (1991, Laurent Heynemann), and her most recent film, A Foreign Field (1993, Charles Sturridge), in which Moreau stars with Lauren Bacall and Alec Guinness. Other highlights include The Queen Margot (1953, Jean Dreville), which has not been shown in the United States since its original release; the uncut version of Eva (1962, Joseph Losey); the rarely seen Mata Hari, Agent H 21 (1964, Jean-Louis Richard), and Joanna Francesa (1973, Carlos Diegues). Alternately playful, seductive, or somber, Moreau brought something truly modern to the screen -- a compelling but ultimately elusive persona. After perfecting her craft as a principal member of the Comedie Frangaise and the Theatre National Populaire, she appeared in such films as Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1957) and The Lovers (1958), the latter of which she created a scandal with her portrayal of an adultress. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Cinema Medeia Nimas

Cinema Medeia Nimas www.medeiafilmes.com 10.06 07.07.2021 Nocturno de Gianfranco Rosi Estreia 10 Junho Programa Cinema Medeia Nimas | 13ª edição | 10.06 — 07.07.2021 | Av. 5 de Outubro, 42 B - 1050-057 Lisboa | Telefone: 213 574 362 | [email protected] 213 574 362 | [email protected] Telefone: 42 B - 1050-057 Lisboa | 5 de Outubro, Medeia Cinema Nimas | 13ª edição 10.06 — 07.07.2021 Av. Programa Os Grandes Mestres do Cinema Italiano Ciclo: Olhares 1ª Parte Transgressivos A partir de 17 Junho A partir de 12 Junho Ciclo: O “Roman Porno” Programa sujeito a alterações de horários no quadro de eventuais novas medidas de contençãoda da propagaçãoNikkatsu da [1971-2016] COVID-19 determinadas pelas autoridades. Consulte a informação sempre actualizada em www.medeiafilmes.com. Continua em exibição Medeia Nimas 10.06 — 07.07.2021 1 Estreias AS ANDORINHAS DE CABUL ENTRE A MORTE Les Hirondelles de Kaboul In Between Dying de Zabou Breitman e Eléa Gobbé-Mévellec de Hilal Baydarov com Simon Abkarian, Zita Hanrot, com Orkhan Iskandarli, Rana Asgarova, Swann Arlaud Huseyn Nasirov, Samir Abbasov França, 2019 – 1h21 | M/14 Azerbaijão, México, EUA, 2020 – 1h28 | M/14 ESTREIA – 10 JUNHO ESTREIA – 11 JUNHO NOCTURNO --------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------- Notturno No Verão de 1998, a cidade de Cabul, no Davud é um jovem incompreendido e de Gianfranco Rosi Afeganistão, era controlada pelos talibãs. inquieto que tenta encontrar a sua família Mohsen e Zunaira são um casal de jovens "verdadeira", aquela que trará amor e Itália, França, Alemanha, 2020 – 1h40 | M/14 que se amam profundamente. Apesar significado à sua vida. -

Coronation Concert

32 RADIO TIMES May 29, 1953 oeojU NE eeoeeoeoeeeeeooeeoeooeooe000000eeoe 0 o The Home Service 3 WEDNESDAY ó 330 m. (908 kcis) EVENING FROM 5. 0 P.M. ö GOGGGGOGGOOOO000009012GGGOGGOGOGOOGGOGOOG0000 5.0 p.m. CHILDREN'S HOUR A nursery sing -song with Doris, Vi, and Gwen 5.15 Regional Round CORONATION CONCERT Coronation Edition Elsie Morison Peter Pears Anne Wood Join with children all over the SOPRANO TENOR CONTRALTO country to answer questions con- cocted by Geoffrey Dearmer and BBC Choral Society A section of Watford Grammar School Boys' Choir posed by David (Chorus -Master, Leslie Woodgate) Conductor, Frank Budden 5.50 Children's Hour prayers BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Conducted by (Leader, Paul Beard) the Rev. George Reid Conductor, Sir Malcolm Sargent PART 1 at 8.0 GOD SAVE THE QUEEN PART 2 at 9.15 5.55 The Weather Shipping and general weather fore- Spring Symphony Benjamin Britten Symphony No. 1, in A flat Elgar casts, followed by a detailed forecast for South -East England Benjamin Britten has said that for two years he was planning a symphony dealing ' not only with the Spring itself, but with the progress of Winter to Spring ana the re -awakening of the earth and life wh ch that means.' At first he intended to use medieval Latin verse; but ` a re -reading of much English lyric verse and a de et Greenwich Time Signal particularly lovely day in East Suffolk, the Suffolk of Constable and Gainsborough,' made him change his mind. Elgar's Symphony in A flat was not only the first that he wrote: is was the first NEWS symphony by an Englishman to be acknowledged as a masterpiece. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

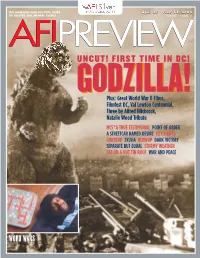

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

The Grierson Effect

Copyright material – 9781844575398 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Notes on Contributors . ix Introduction . 1 Zoë Druick and Deane Williams 1 John Grierson and the United States . 13 Stephen Charbonneau 2 John Grierson and Russian Cinema: An Uneasy Dialogue . 29 Julia Vassilieva 3 To Play The Part That Was in Fact His/Her Own . 43 Brian Winston 4 Translating Grierson: Japan . 59 Abé Markus Nornes 5 A Social Poetics of Documentary: Grierson and the Scandinavian Documentary Tradition . 79 Ib Bondebjerg 6 The Griersonian Influence and Its Challenges: Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong (1939–73) . 93 Ian Aitken 7 Grierson in Canada . 105 Zoë Druick 8 Imperial Relations with Polynesian Romantics: The John Grierson Effect in New Zealand . 121 Simon Sigley 9 The Grierson Cinema: Australia . 139 Deane Williams 10 John Grierson in India: The Films Division under the Influence? . 153 Camille Deprez Copyright material – 9781844575398 11 Grierson in Ireland . 169 Jerry White 12 White Fathers Hear Dark Voices? John Grierson and British Colonial Africa at the End of Empire . 187 Martin Stollery 13 Grierson, Afrikaner Nationalism and South Africa . 209 Keyan G. Tomaselli 14 Grierson and Latin America: Encounters, Dialogues and Legacies . 223 Mariano Mestman and María Luisa Ortega Select Bibliography . 239 Appendix: John Grierson Biographical Timeline . 245 Index . 249 Copyright material – 9781844575398 Introduction Zoë Druick and Deane Williams Documentary is cheap: it is, on all considerations of public accountancy, safe. If it fails for the theatres it may, by manipulation, be accommodated non-theatrically in one of half a dozen ways. Moreover, by reason of its cheapness, it permits a maximum amount of production and a maximum amount of directorial training against the future, on a limited sum.