The in the UNITED STATES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dutch Elm Disease

2/16/2021 Dutch Elm Disease Published on Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment (https://ag.umass.edu) Dutch Elm Disease [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] Dutch elm disease (DED) is a lethal vascular wilt disease of American elm (Ulmus americana) that is caused by Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and O. ulmi. While once widespread in the region, O. ulmi has been displaced by the more aggressive O. novo-ulmi and is now believed to be uncommon to rare in the region. Both O. novo-ulmi and O. ulmi are non-native to North America and Europe. Overland spread of DED from diseased to healthy elms is facilitated by the native elm bark beetle (Hylurgopinus rufipes) and European elm bark beetle (Scolytus multistriatus). The disease also spreads from diseased to healthy trees through root grafts when elms are in close proximity to one another. Hosts All North American elms are susceptible to DED to some degree. American elm, the most abundant elm species in New England, is highly susceptible while the two other native elms occasionally found in landscape settings, rock elm (U. thomasii) and slippery elm (U. rubra), vary from susceptible to somewhat resistant. Several DED-resistant cultivars of American elm have been developed, with Princeton (U. americana ′Princeton′) and Valley Forge (U. americana ′Valley Forge′) the most abundant in area nurseries. While both cultivars offer good to excellent resistance to DED, they both suffer from poor canopy structure and are prone to stem and branch breakage under high winds and snow. Additional cultivars that are not as widely available, but offer more desirable canopy structure and form, include Jefferson (U. -

U.S. Domestic Japanese Beetle Harmonization Plan"

U.S. Domestic Japanese Beetle Harmonization Plan Adopted by the National Plant Board August 19, 1998 Last Revision June 20, 2016 i Collins National Plant Board OsamaEI-Lissy Deputy Administrator Plant Proteclion and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture CraigRegelbrugge Senior Yice President- Industry Advocacy & Research AmericanHort TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECTIVE SUMMARY 1 I. GOALS AND BACKGROUND 1 II. CRITERIA FOR DETERMINING JAPANESE BEETLE INFESTATION STATUS 2 III. DEFINITIONS 3 IV. REGULATORY STRATEGIES 3 Category 1 - Uninfested/Quarantine Pest 3 Category 2 – Uninfested or Partially Infested 4 Category 3 – Partially or Generally Infested 4 Category 4 –Not Known To Be Infested/Unlikely To Become Established 4 V. HARMONIZATION PLAN COMMITTEES AND MEMBERSHIP 5 VI. HARMONIZATION PLAN MODIFICATIONS 5 VII. REGULATORY TREATMENT REQUIREMENTS AND PESTICIDE DISCLAIMERS 6 APPENDIX 1. SHIPMENT TO CATEGORY 1 STATES 7 Certification Options 1-4 1. Production in an Approved Japanese Beetle Free Greenhouse/Screenhouse 7 2. Production During a Pest Free Window 7 3. Application of Approved Regulatory Treatments 8 4. Detection Survey for Origin Certification 10 Adult Japanese Beetle Mitigation Requirements 11 APPENDIX 2. SHIPMENT TO CATEGORY 2 STATES 14 Certification Options 1-5 1. Application of Approved Regulatory Treatments 14 2. Japanese Beetle Nursery Trapping Program 15 3. Field Grown Nursery Stock Accreditation Program 16 4. Containerized Nursery Stock Accreditation Program 17 5. Shipment of Sod 18 Adult Japanese Beetle Mitigation Requirements 18 APPENDIX 3: SHIPMENT INTO CANADA FROM THE UNITED STATES 21 APPENDIX 4: STATEWIDE DETECTION & DELIMITING SURVEY 23 APPENDIX 5. BIOLOGY AND PEST RISK ANALYSIS 25 APPENDIX 6. -

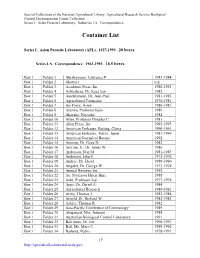

Container List

Special Collections of the National Agricultural Library: Agricultural Research Service Biological Control Documentation Center Collection Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory. Subseries I.A. Correspondence. Container List Series I. Asian Parasite Laboratory (APL). 1927-1993. 20 boxes. Series I.A. Correspondence. 1963-1993. 16.5 boxes. Box 1 Folder 1 Abrahamson, Lawrence P. 1983-1984 Box 1 Folder 2 Abstract n.d. Box 1 Folder 3 Academic Press, Inc. 1986-1993 Box 1 Folder 4 Achterberg, Dr. Kees van 1982 Box 1 Folder 5 Aeschlimann, Dr. Jean-Paul 1981-1985 Box 1 Folder 6 Agricultural Counselor 1976-1981 Box 1 Folder 7 Air Force, Army 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 8 Aizawa, Professor Keio 1986 Box 1 Folder 9 Akasaka, Naoyuki 1982 Box 1 Folder 10 Allen, Professor Douglas C. 1981 Box 1 Folder 11 Allen Press, Inc. 1992-1993 Box 1 Folder 12 American Embassy, Beijing, China 1990-1991 Box 1 Folder 13 American Embassy, Tokyo, Japan 1981-1990 Box 1 Folder 14 American Journal of Botany 1992 Box 1 Folder 15 Amman, Dr. Gene D. 1982 Box 1 Folder 16 Amrine, Jr., Dr. James W. 1986 Box 1 Folder 17 Anderson, Don M. 1981-1983 Box 1 Folder 18 Anderson, John F. 1975-1976 Box 1 Folder 19 Andres, Dr. Lloyd 1989-1990 Box 1 Folder 20 Angalet, Dr. George W. 1973-1978 Box 1 Folder 21 Annual Reviews Inc. 1992 Box 1 Folder 22 Ao, Professor Hsien-Bine 1988 Box 1 Folder 23 Aoki, Professor Joji 1977-1978 Box 1 Folder 24 Apps, Dr. Darrel A. 1984 Box 1 Folder 25 Agricultural Research 1980-1981 Box 1 Folder 26 Army, Thomas J. -

Japanese Beetles L

U N I V E R S I T Y O F K E N T U C K Y COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ENTOMOLOGY ENTFACT-409 JAPANESE BEETLES L. H. Townsend, Extension Entomologist Description and Habits doing best in warm, slightly moist soil that has plenty Adult Japanese beetles are 3/8-inch long metallic green of organic matter and tender grasses. However, they beetles with copper-brown wing covers. Five small can survive in almost any soil in which plants can live. white tufts project from under the wing covers on each side, and a sixth pair at the tip of the abdomen, Late summer rainfall is needed to keep eggs and distinguish them from similar beetles. newly-hatched grubs from drying out. During dry summers, females lay their eggs in low, poorly drained Adults emerge from the ground and begin feeding on areas. The grubs are relatively drought resistant and plants in June. Individual beetles live about 30 to 45 will move deeper into the soil if conditions become days. Activity is concentrated over a four to six week very dry. Japanese beetle grubs also can withstand high period, beginning in July, after which the beetles soil moisture, so excessive rainfall or heavy watering gradually die. of lawns does not bother them. Grubs usually move less than 30 inches in sod or turf; however, Japanese beetles can feed on about 300 species of measurements have shown that grubs can move as plants ranging from roses to poison ivy. Odor seems to much as 16 feet in fallow soil. -

Japanese Beetles This Year Again Proposes for a Dramatic Increase in the Populations of Japanese Beetles

Japanese Beetles This year again proposes for a dramatic increase in the populations of Japanese beetles. These beetles can be very damaging in both their adult and larval stage. Beetles are approximately 3/4" long, and are easily distinguished by their blue/green//brown/silver color, which is shiny and makes them look like they are made out of metal. Typically they are unlike anything you are used to seeing. The most damaging and expensive injury caused by Japanese beetle is by its larval stage feeding on the roots of turf grass. Browning turf, in spotted areas, which can be pulled up in clumps is a sure sign. The less concerning, but most noticeable, damage occurs to the leaves of many different species of plants. Leaves will be eaten, with only the leaf veins remaining (looks similar to lace). Trees can be treated with a foliar application, which will only be effective for only a few days, an injected systemic insecticide, or by soil applied insecticide. The truly effective, and least costly, way to treat for beetles is not to treat the tree at all, but to eliminate them in the larval stage (in the soil). The beetles lay eggs in the soil, which over-winter and mature as grubs, which feed on grass and other roots. A turf grub control treatment in early to mid May will reduce and control the adult populations. It is very difficult to fully eliminate the beetles as they may reside in your neighbors turf as well. The solution is to take this information to your neighbors and institute a cooperative plan to treat the turf, and/or otherwise manage the pest in the spring. -

Biological Control of the Japanese Beetle from 1920 to 1964 Might Be More Available to Other Entomologists and the General Public

~ 12.8 ~1112.5 11.0 :it il~~ "I"~ 1.0 W .. !lMI :: W12.2 :: w 12.2 ~ IW .. L:I. W !!!ll!iIil III : ~ '_0 :: ~ 2.0 1.1 ........ ~ 1.1 .. .... ~ --- - 1111,1.8 '"" 1.8 25 111111.25 111111.4 111111.6 111111. 1/11/1. 4 111111. 6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAl, BUReAU or STANDARDS·1963·A NATIONAL BUREAU or STANDARDS·1963-A BIOL()GICAL CONTROL Of The JAPi\NESE BEETLE By 'W~lter E. Fleming Technical Bulletin No. 1383 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Washington, D.C. Issued February 1968 Forsale hy the S u peri n tenden t ofDoeumen ts, U.S. Go,",ernmentPrinting Office Washington, H.C. 20402 - l)rice 30 eents Contents Page Predators and parasites for control of beetle______________________________ 3 Xative predators llnd parasites______________________________________ 3 fnsedivorous birds__ _ _ ______ ._______________________________ 3 Tonds _________________________________________________ ------ 4 11anlnln~ _____________________________________________ ----- - 4 Predt\ceous insects _________________________________ --- ___ - ----- 5 Parasit ie insects ______________________________________ -------- - 6 Foreign predaceous and p:lrasitic insects_____________________________ 6 Explorations _____________ --________________________ - ________ -- 7 Biology of import:mt parasites and a predator in Far EasL ________ - 8 Hyperparasites in Far East.____________________________________ 18 Shipping parasites and predalors lo United Slales_________________ 19 Rearing imported -

Japanese Beetle Rufus Isaacs, Zsofia Szendrei and John C

Extension Bulletin E-2845 • New • May 2003 MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY Japanese Beetle Rufus Isaacs, Zsofia Szendrei and John C. Wise Department of Entomology, Michigan State University Japanese Beetle features of this beetle. Males and females frequently Popillia japonica Newman congregate on plants exposed to sunlight, where they (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) feed and mate. Introduction Adult beetles feed on the foliage and fruits of about The Japanese beetle was introduced into New Jersey 300 plant species, including fruits, field and garden around 1911. Since then, readily available food for crops, ornamentals and many wild plants. Among the adults, abundant turf for larvae and low levels of small fruit crops, adult Japanese beetles prefer natural enemies have contributed to the buildup and grape, raspberry and blackberry over many other spread of this insect across eastern North America. plants, including blueberry. Adult Japanese beetles In Michigan, the presence of adult beetles has been skeletonize the foliage, consuming the soft mesophyll reported from every county in the lower two-thirds of tissues between the veins, leaving a lacelike skeleton. the Lower Peninsula. This factsheet provides general Beetles cluster at the tops of plants, so the upper information on Japanese beetle and management canopy is usually defoliated more severely. In many approaches for use in blueberries and other perennial fruit crops, foliar damage is unlikely to affect yield. fruit crops. Once fruit becomes ripe, beetles may feed and aggregate on ripening fruit. Identification Adults are about 13 mm long (Figure 1). The head Eggs are 1 to 2 mm in diameter, spherical and white and thorax are metallic green, and the rest of the (Figure 2). -

Japanese Beetles – How Do I Keep My Plants from Looking Like Swiss Cheese?

June 2018 Japanese Beetles – How Do I Keep My Plants From Looking Like Swiss Cheese? Japanese beetle season is almost upon us – probably about 10-14 days away. During the last couple summers Japanese beetles have been a true headache for many gardeners. Defoliated plants – in some cases entire trees - look horrible and no matter what you do they seem to keep coming. So, what’s the best strategy for managing them? Below are some tips to help minimize damage in your landscape. But first - realize that when Japanese beetles first come into an area, beetle numbers build for about 5 to 8 years, reaching a peak level. After that time, beetle populations drop and, although they never disappear, damage becomes less severe. So the light at the end of the tunnel is the amount of plant damage seen during the peak years will lessen naturally in time. Some areas of eastern Nebraska have been dealing with Japanese beetles for several years already, while others still haven’t seen their first beetle. Even within Lincoln, some sections of town have had problems for several years, while other areas haven’t seen them yet. So gardeners across Lincoln are at different points on the Japanese beetle infestation timeline. What Do They Look Like? Both adult and immature Japanese beetles are damaging to landscapes. The adult beetles are shaped similar to our common June beetles, but a little smaller - about ½ inch long. Their head and thorax is metallic green, their wing covers are copper brown. But you have to look closely sometimes to see these colors. -

Trees to Avoid Planting in the Midwest and Some Excellent Alternatives

Trees to Avoid Planting in the Midwest and Some Excellent Alternatives Dr. Laura G. Jull Dept. of Horticulture, UW-Madison Trees provide us with many environmental, aesthetic, functional, and economic benefits. Tree selection is one of the most important considerations when a homeowner, nurserymen, or landscaper is deciding what species to grow or plant. Many questions need to be answered including size, location, site characteristics, aesthetic features, pest susceptibility, hardiness, and maintenance considerations. Some trees can become a maintenance headache due to their inherent pest problems or lack of structural integrity. The trees represented in this story have not generally performed well in urban and suburban areas of the Midwest. Some are susceptible to insects and diseases, and some have severe structural problems such as being weak- wooded or prone to girdling roots or included bark formation. Others have cultural problems such as intolerance to high pH, road salt, drought, and poor drainage. A few tree species are invasive and should be avoided near sensitive areas or seed dispersal into woodlands could occur. Some of these trees may do quite well in other parts of the U.S., so my intention is not to apply a blanket statement for all these trees to all situations. Invasiveness and pest susceptibility can vary geographically. The article is based on more than 25 years of field experience and data collected from numerous states’ plant disease and insect diagnostic clinics, and conversations with arborists, nurseries, landscapers, and extension personnel. There are alternative species that can be used and are mentioned here. These alternative tree species have performed well in USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 4b. -

Disease Resistant Elm Selections Bruce R

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Disease Resistant Elm Selections Bruce R. Fraedrich, PhD, Plant Pathology Many hybrids and selections of Asian elm that have reliable resistance to Dutch elm disease (DED) are available for landscape planting. In addition to disease resistance, these elms tolerate urban stress and are adapted to a wide range of soil conditions. These selections are suitable for routine planting in areas where they are adapted to the climate. Descriptions in this report are based primarily on performance of trees growing in the arboretum at the Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories in Charlotte, North Carolina (Zone 8). Accolade Elm in Northern Plains States where low temperatures and low rainfall limit successful use of other cultivars. Ulmus davidiana var. japonica ‘Morton’ A selection of Japanese elm, Accolade elm exhibits Commendation Elm strong resistance to DED and is expected to be resistant to elm yellows. This selection is a favored host Ulmus ‘Morton Stalwart’ of Japanese beetle which can cause defoliation in years A hybrid between U. carpinifolia, U. pumila and U. with heavy outbreaks. Accolade grows rapidly and davidiana var. japonica, Commendation has the has a vase shape with a mature height of 60 feet. It has fastest growth of any of the Morton Arboretum been planted extensively in many Midwestern cities introductions. This cultivar has an upright, vase shape (zone 4). Danada Charm (Ulmus ‘Morton Red Tip’) is but has a distinctively wider crown spread than an open pollinated selection from Accolade and has Accolade or Triumph. The leaves are larger than most similar habit and appearance. Danada Charm does hybrid elms and approach the same size as American not grow as rapidly as Accolade or Triumph in elm. -

White Grubs (Japanese Beetle, May/June Beetle, Masked Chafer, Green June Beetle, European Chafer, Asiatic Garden Beetle, Oriental Beetle, Black Turfgrass Ataenius)

White Grubs (Japanese Beetle, May/June Beetle, Masked Chafer, Green June Beetle, European Chafer, Asiatic Garden Beetle, Oriental Beetle, Black Turfgrass Ataenius) There are 8 different white grubs that are commonly known to cause turfgrass plant damage. They include the Japanese beetle, May and June beetle, masked chafer, green June beetle, European chafer, Asiatic garden beetle, oriental beetle, and black turfgrass ataenius. They all do the most damage in their larval stage, although some adults can also cause damage. Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica) Japanese beetles are concentrated mostly in the northeastern and Mid Atlantic states. The Japanese beetle larvae are the primary cause of turf damage. They feed on turfgrass roots, which causes yellowing and a wilting, thinning appearance to the plants. Turf that has been damaged can easily be rolled or lifted back from the soil because the grubs have eaten through the fibrous roots. Typical Japanese beetle raster pattern. Typical Japanese beetle adult. Pictures: http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu/orn/beetles/Japanese_beetle_02.htm; http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/factsheet/ENT-100-06PR.pdf; http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/2000/2510.html Text: Handbook of Turfgrass Insect Pests by Rick Brandenburg and Michael Villani For more information on Japanese beetles: Ohio State University Extension Fact Sheet – Japanese Beetle http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/2000/2504.html University of Maryland – Japanese Beetle http://iaa.umd.edu/umturf/Insects/japanese_beetle.html Utah State University Extension Fact Sheet – Japanese Beetle http://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/factsheet/ENT-100-06PR.pdf University of Florida – Japanese Beetle http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN630 May and June Beetles (Phyllophaga species) May and June beetles can be found all across the United States. -

View the PDF File of the Tachinid Times, Issue 18

The Tachinid Times ISSUE 18 February 2005 Jim O’Hara, editor Invertebrate Biodiversity Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada C.E.F., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0C6 Correspondence: [email protected] The Tachinid Times continues to be offered in submissions, and the newsletter as a whole is reviewed hardcopy and online, with both versions having identical internally within my organization before it is posted on the pagination and appearance except that the figures in the Internet and distributed in hardcopy. Articles in The online version are produced in colour and the figures in the Tachinid Times are cited in Zoological Record. printed version are in black and white. The online version is available as a PDF file (ca. 1.5 MB in size) at the North Benno Herting, 1923–2004 (by H.-P. Tschorsnig) American Dipterists Society (NADS) website at: http:// At the age of 80 years, one of the most outstanding www.nadsdiptera.org/Tach/TTimes/TThome.htm. experts on tachinids, Dr. Benno Herting, died in Freiberg I would like to dedicate this issue of The Tachinid am Neckar (south-western Germany) on 19 July 2004. Times to a leader in tachinid systematics who passed away Benno Wilhelm Herting was born on 30 December in 2004, Dr. Benno Herting. His high standards of research 1923 in Bochum (north-western Germany) as a single earned him a respected position among modern tachinid child of a Catholic schoolteacher. After he finished school, systematists. Through his papers, advice and identifications, he was forced to join the military. To his great fortune – he aided many researchers and students in systematics, according to his own words – he was released from the biological control, faunistics and ecology.