An Ecological and Land Use Study 05' Burns Bog, Delta, British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter of the Entomological Society of British Columbia

Boreus Newsletter of the Entomological Society of British Columbia December 2006 Volume 26 (2) Table of Contents The Executive................................................2 Publications of the ESBC ........................3 Boreus Editor’s Notes.......................................5 Society Business .............................................6 Executive Reports ......................................... 11 Editor’s Report – Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia. 11 Web Editor’s Report ........................... 12 Report of the ESBC Regional Director....... 13 Boreus Report................................... 16 2006 AGM and Aquatic Entomology Symposium ...... 16 Upcoming Events .......................................... 21 New and Upcoming Publications........................ 24 Notes from the Field: Bute Inlet trip yielded a few new records ................................................ 27 Interesting Entomological Information ................ 28 Notes and News............................................ 28 ESC Gold Metal Awarded to Richard Ring .. 29 Entomological Humour ........................ 32 Requests for information on the Monarch Butterfly in Canada ............................ 33 In Memory, John Douglas “Jack” Gregson.. 34 In Memory, Dr. Albert "Bert" Turnbull ...... 36 Top to bottom photographs: Spotted Lake outside Osoyoos; Rob Cannings looking for the elusive Tanypteryx hageni at Herman Lake, Terrace; day of collecting at White Lake, near Penticton; dragonfly at Nighthawk Ecoreserve near Keremeos -

Nneef~)\I^ Petition to Protect Unprotecte.D Bums Bog

genda PETITIONS TO PROTECT UNPROTECTED BURNS BOG SUBMITTED ON JUNE 20, 2016 BY ELIZA OLSON FOR THE BURNS BOG CONSERVATION SOCIETY 41 SIGNATURE HARD COPY PETITION 132 ADDITIONAL SIGNATURE ON-LINE PETITION (Please Note: Includes the 153 Signature On-Line Previously Submitted On June 8, 2016) ONTABLE E. 03 DEPT: Comments: nneef~)\i^ Petition to Protect Unprotecte.d Bums Bog To the Honorable, the Council of the Corporation of Delta in the Province of British Columbia in 9.Ol111Cil Assembled The petition of the undersigned; residents of the Province of British Columbia, states that; Whereas: A business con~ortium led by develop~rs are attempting to convert unprotected areas of Burns Bog into commercial, industrial and residential developments; and (:.,." Whereas: the peatland is part of the largest raised peat bog on the west coast of North America; and , !i, Whereas: former Premier Campbell attempted to buy this unprotected peatland as a buffer zone in 2004; and ~ ::0 Whereas: these peatlands are critical to the long term survival of the Burns Bog Conservation Area; and . .0 w Whereas: these peatlands, along with the Burns Bog Conservation Area are critical to the ecosystem that supp~ • '_ . " , ' . , - 1..... 1 the Pacific flyway, the largest salmon-bearing river in the world, the Fraser River; and Whereas: Canada has signed a number of international agreements, including the Ramsar Convention that . • ~ ! recognizes Burns Bog as a wetland of international importance and the Migratory Bird Co~vention Act; Your petitioners requ~st that the Honourable Council demand that the Corporation of Delta of British Columbia publicly condemn the proposed industrialization of peatland that is part of the largest raised peatland on the west coast of North America and declare its commitment to protect all of Burns Bog peatland. -

2007 Annual Report for the City of Richmond

Cullen Commission City of Richmond Records Page 298 -·... ,. �......... -· 2007 Annual Report Ci1y or llich111011d. lhiti�li Col11111hi:1. C.111:1d:1 For the year ended December 31, 2007 Cullen Commission City of Richmond Records Page 299 City of Richmond's Vision: To be the most appealing, livable, and well-managed community in Canada Cityof Richmond British Collllllbia, Canada 2007 Annual Report For the year ended December 31, 2007 Cullen Commission City of Richmond Records Page 300 Cover Photo: Rowers have become a familiar sight along the Fraser River's Middle Arm with the opening of UBC's JohnMS Lecky Boathouse, offering both competitive and community rowing and paddling sports programs. This report was prepared by the City of Richmond Business and Financial Services and Corporate Services Departments. Design, layout and production by the City of Richmond Production Centre C '2007 City of Richmond Cullen Commission City of Richmond Records Page 301 Table of Contents Introductory Section ......................................................................................................................... i Message from the Mayor .......................................................................................................................... ii Richmond City Council ........................................................................................................................... iii City of Richmond Organizational Chart .................................................................................................. -

Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska

Zootaxa 4666 (1): 001–180 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4666.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:BA01E30E-7F64-49AB-910A-7EE6E597A4A4 ZOOTAXA 4666 Checklist of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska VALERIE M. BEHAN-PELLETIER1,3 & ZOË LINDO1 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A0C6, Canada. 2Department of Biology, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by T. Pfingstl: 26 Jul. 2019; published: 6 Sept. 2019 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 VALERIE M. BEHAN-PELLETIER & ZOË LINDO Checklist of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska (Zootaxa 4666) 180 pp.; 30 cm. 6 Sept. 2019 ISBN 978-1-77670-761-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77670-762-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2019 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] https://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 4666 (1) © 2019 Magnolia Press BEHAN-PELLETIER & LINDO Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................5 -

Appendix I Climate Normals

84 APPENDIX I CLIMATE NORMALS 85 APPENDIX I: CLIMATE NORMALS (1951 - 1980) NANAIMO AIRPORT (49 Degrees 3 Minutes North / 123 Degrees 52 Feet Minutes TOTAL BRIGHT SUNSHINE (HOURS) 1951-81 JANUARY 50.3 FEBRUARY 78.7 MARCH 125.9 APRIL 166.3 MAY 231.7 JUNE 218.6 JULY 287.4 AUGUST 244.6 SEPTEMBER 177.1 OCTOBER 122.0 NOVEMBER 65.1 DECEMBER 43.4 YEAR 1,811.1 86 87 88 FROST AVERAGES AND EXTREMES: NANAIMO AIRPORT AVERAGES BASED ON 1951 - 1980 PERIOD OF RECORD YEARS: 30 Frost-free Period (days): 155 Last Frost (Spring): May 3rd First Frost (Fall): October 6th EXTREMES BASED ON FULL PERIOD OF RECORD YEARS: 34 LAST FROST (SPRING) Earliest: April 9th Latest: May 31st FIRST FROST (FALL) Earliest: September 12th Latest: November 20th LONGEST Last Frost (Spring): April 20th First Frost (Fall): November 20th Number of Days: 213 SHORTEST Last Frost (Spring): May 16th First Frost (Fall): September 12th Number of Days: 118 89 APPENDIX II: CLASSIFICATION SCHEME FOR CLIMATIC SUITABILITY FOR OUTDOOR RECREATION 90 APPENDIX II: CLASSIFICATION SCHEME FOR CLIMATIC SUITABILITY FOR OUTDOOR RECREATION IN B.C., R. C. BENNETT (1977) Outdoor recreation involves a complex interaction between people and the physical environment. Since weather is a key determiner of personal comfort, climate is an important consideration in the assessment of outdoor recreation suitability. Personal comfort levels are difficult to establish and require the assessment of numerous variables. However, reliable classification schemes have been developed. Personal comfort variables include ambient air temperature, wind, relative humidity, solar radiation, as well as activity levels and clothing. -

And Ecological Cycles of the Fraser River Estuary. They Strongly Modify the Effects of Runoff and Tides

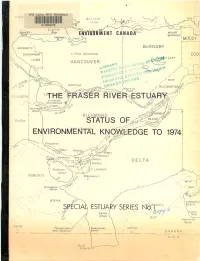

DFO - Library / MPO - Bibliotheque &ttt?«r4 J t taf*t 01008878 ...... eog/fsh -••• •-*&.,.., i MOUNT &&o# >—"••• eMhOTTeHT CANADA w • /• MOODY ~-~-x yr VT BURNABY '••• V* '•••: •• .V lands ; tJifilBP *"« VANCOUVER '••••.'' \/ .-• tsi--* / rf<^«?S^s» -. ./ /A I SSTH=E fpftSlft RIV#^STI#R^> '':'*K:%, *^/ ! HiQn4( "'" "~7^ RICHMOND A^r•••::< ,.•••" a& ^/>.v • *£M#tf ; STATUS Ofjf^W ENVIRONI^feWTAl KNGSee6GE TO 1974 /kV /It-"" •' £*^ / v«.1 \ "••••• ..'•••••,':v"' .,.""-^..,.(':'h';,-K.,n,1 i DELTA W*sthom '•••>.. ^•- -«A nosefirs >y ' V*^.''i?"" ,.•:! ^,,rt- '&&ms»fcA C ^i5 .^/i? . /^v/?/ \ ,.-••"" /' BANK \ \A •::••<: •:.:-•. mOMs ESTUARY SERIES NS!1&QyNOA#Y A>r/ J 6' ^>; >" fittittt I \ 12.^*00' CA N A 0 A U< S. A, V /•;';v;;•.-:. ••/•;; •.:•' ENVIRONMENT CANADA THE FRASER RIVER ESTUARY STATUS OF ENVIRONMENTAL KNOWLEDGE TO 1974 REPORT OF THE ESTUARY WORKING GROUP DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT REGIONAL BOARD PACIFIC REGION ACIFICBIOUO^ F1SH^Jisve .,sHCOLUMBIA LINDSAY M. HOOS and GLEN A. PACKMAN Under the Direction of Dr. M. Waldichuk Fisheries and Marine Service Pacific Environment Institute West Vancouver, B.C. With A Geology Section by Dr. John L. Luternauer Geological Survey of Canada Vancouver, B.C. Special Estuary Series No.1 SEPTEMBER 30, 1974 SATELLITE PHOTO OF THE FRASER RIVER ESTUARY AND CONTIGUOUS WATERS, JULY 30, 1972. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents i List of Figures iv List of Tables vi List of Appendices vii Preface . ix Acknowledgements xiii Summary xiv 1. Introduction 1 2. Sources of Information 7 (i) Environment Canada 7 (ii) Other Agencies 8 3. Geology 10 (i) Geographic-geologic setting and geologic history 12 (ii) Areal distribution of surficial sediments and dispersal patterns of water-borne sediments . -

Knowledge, Attitudes and Activities Around Wildlife and Nature a Case Study of Richmond, BC

Knowledge, attitudes and activities around wildlife and nature A case study of Richmond, BC Linda Love, MPA candidate School of Public Administration University of Victoria July 2015 Client: Marie Fenwick, Manager, Parks Programs City of Richmond Supervisor: Dr. Lynda Gagné, Assistant Professor School of Public Administration, University of Victoria Second Reader: Dr. Kimberly Speers, Assistant Teaching Professor School of Public Administration, University of Victoria Chair: Dr. Richard Marcy, Assistant Professor School of Public Administration, University of Victoria ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the support of the City of Richmond. Your support and enthusiasm for the project made this research both fun and rewarding. While I know there were many others behind the scenes, I want to particularly thank Marie Fenwick for believing that this research was useful, Kris Bauder for sharing her wisdom and experience about nature in Richmond, Andrea Lee Hamilton for her communication expertise, and Emily Toda for everything she did to get the survey up and running and helping me navigate the Let’s Talk Richmond tool. And of course to my family for keeping me fed and reminding me to have fun - you know I never would have made it without you! [1-i] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION This report summarizes research conducted for the City of Richmond, a fast growing community situated on an island bordered by the Fraser River and the Georgia Strait. The City has a wealth of wildlife and possesses unique ecological characteristics. In recent years, Richmond has experienced a significant amount of social and cultural change. The objective of this research project was to better understand the attitudes that Richmond residents have towards wildlife and nature in the City, and to identify any differences in these attitudes between socio-demographic groups. -

An Environmental History of the City of Vancouver Landfill in Delta, 1958–1981

Dumping Like a State: An Environmental History of the City of Vancouver Landfill in Delta, 1958–1981 by Hailey Venn B.A. (History), Simon Fraser University, 2017 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Hailey Venn 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction orre-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Hailey Venn Degree: Master of Arts Thesis title: Dumping Like a State: An Environmental History of the City of Vancouver Landfill in Delta, 1958 – 1981 Committee: Chair: Sarah Walshaw Senior Lecturer, History Tina Adcock Supervisor Assistant Professor, History Joseph E. Taylor III Co-supervisor Professor, History Nicolas Kenny Committee Member Associate Professor, History Arn Keeling Examiner Associate Professor, Geography Memorial University of Newfoundland ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract In 1966, the City of Vancouver opened a new landfill in Burns Bog, in the nearby municipality of Delta. This is an environmental history of its creation and first sixteen years of operation. Although the landfill resembled other high modernist projects in postwar Canada, this thesis argues it is best understood as an example of “mundane modernism.” The landfill’s planning and operation aligned with broader contemporary American and Canadian practices of cost-effective waste disposal. It was an unspectacular project to which Deltans offered little initial resistance. Officials therefore had no need to demonstrate technoscientific expertise to manufacture citizens' consent. Yet the landfill soon posed environmental nuisances and hazards to Delta’s residents, including leachate, the liquid waste a landfill produces. -

Self-Guided Plant Walks

Self-Guided Plant Walks Washington Native Plant Society Central Puget Sound Chapter Over the course of many years, the plant walks listed in this booklet provided WNPS members with interesting outings whether it be winter, spring, summer or fall. We hope these walk descriptions will encourage you to get out and explore! These walks were published on wnps.org from 1999-2011 by the Central Puget Sound Chapter and organized by month. In 2017 they were compiled into this booklet for historical use. Species names, urls, emails, directions, and trail data will not be updated. If you are interested in traveling to a site, please call the property manager (city, county, ranger station, etc.) to ensure the trail is open and passable for safe travel. To view updated species names, visit the UW Burke Herbarium Image Collection website at http://biology.burke.washington.edu/herbarium/imagecollection.php. Compiled October 28, 2017 Contents February .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Discovery Park Loop - February 2011 .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sol Duc Falls - February 2010 ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Meadowdale County Park - February -

A History of Settler Place-Making in Burns Bog, British Columbia

From Reclamation to Conservation: A History of Settler Place-Making in Burns Bog, British Columbia By: Cameron Butler Supervised by: Catriona Sandilands A Major Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada August 31, 2019 Abstract Wetlands are, in the Canadian settler imaginary, ambiguous spaces that are neither strictly landmasses nor only bodies of water. This paper explores how Canadian settler-colonialism has incorporated wetlands into systems of land ownership and control by tracing the history a specific wetland, a peat bog known as Burns Bog since the 1930s in the area settlers call Delta, British Columbia. Given its presence as one of the largest wetlands in the region, settlers failed to drain the bog in its entirety. As a result, the bog persisted throughout the history of settlers’ presence on the west coast and has been subjected to waves of settler approaches, making it an ideal case study to consider how ongoing settler-colonialism has shaped, and continues to shape, wetlands. Previous historical works on wetlands in Canada and the United States have documented how early settlers, through to roughly the mid-twentieth century, worked to “reclaim” wetlands and transform them into arable land. However, these accounts have often neglected to continue their analysis of settler-colonialism beyond this period and have, as a result, treated settlers’ more contemporary views of wetlands -- as ecologically valuable ecosystems that need to be conserved or restored -- as a break in colonial dynamics. This research intervenes in this existing body of work by treating shifting practices towards wetlands as successive stages in efforts to incorporate wetlands into settler-colonial logics. -

Self Guided Nature Walk Brochure

Welcome to RICHMOND NATURE PARK: the Richmond CONTEXT MAP OAK ST Nature Park Self-Guided You are about to take a trip back in time, more than 13,000 years to the end of the Ice Age. You will travel Nature Walk back and see the changing face of nature in Richmond. This booklet will guide you along an easy walk that takes from west Vancouver east Vancouver from about 30 minutes. The numbers in this book match the numbers on the stakes along the trail. Please stay on the trail and respect the plants and animals that live here. There are litter containers on the HIGHWAY 99 trail. Enjoy your walk. NO 5 RD HIGHWAY 91 HIGHWAY 91 RICHMOND NATURE STUDY TRAILS ETIQUETTE CENTRE RICHMOND NATURE PARK LEGEND WESTMINSTER HWY Wood-chip trail NO 5 RD NO 4 RD 4 NO Boardwalk SHELL RD from Delta Wheelchair Accessible Viewing Platform Picnic Area Playground m 8k Washrooms . BOG 1 FOREST TRAIL The Nature Park is open daily FOREST FOREST from dawn to dusk. BOG FOREST BOG The Nature House is open daily 9:00am-5:00pm Q U Admission is by donation AK I N G m km TR k AIL 1.6 3 For more information about 8 . 0 IL TIME TRAIL Richmond Nature Park and its programs A SELF-GUIDED R NATURE WALK please call 604-718-6188 T E discover M or email [email protected] I T IL Richmond Nature Park A .3 R 5 T Richmond... k D BOG m 11851 Westminster Highway, Richmond, B.C. -

Mavor and Council External Correspondence Summary H 02 (August 16, 2010) •

Mavor and Council External Correspondence Summary H 02 (August 16, 2010) • FROM TOPIC DEPT. A.T. # Regina vs. Carol Berner! Message to the J. Cessford, Chief 303 Police Officers, Civilian Staff and Volunteers POLICE 106125 Constable, Delta Police of the Delta Police Department National Post Story: Edmonton Bylaw Aims POLICE 304 T. Armstrong 106147 to Reduce Motorcycle Noise CC: Bylaws D. Welch, Local FIRE: Farmed Animal Mass Carcass Disposal 305 Government Program Emergency 106148 Emergency Planning Services, UBCM Planning Mayor R. Drew, Chair, 306 Lower Mainland Treaty Federal Additions to Reserve (ATR) Policy HR&CP 106037 Advisorv Committee L.E. Jackson, Chair, Burns Bog Ecological Conservation Area - 307 Metro Vancouver Board Delta Council May 17, 2010 HR&CP 106071 Recommendations 308 J. Cummins, MP Enabling Accessibility Fund HR&CP 106144 309 M. Dunnaway Aircraft Noise in North Delta HR&CP 106150 310 GJ Kurucz Delta Nature Reserve PR&C 105988 311 J. Wightman Tsawwassen Sun Fest & Recycling PR&C 106153 . FINANCE 312 K. Furneaux, CGA Implications of Legalized Secondary Suites 106146 CC:CP&D < E. Olson, President, Minutes of March 15, 2010 Meeting: Section 313 Burns Bog Conservation CA&ENV 106016 Societv 14, Species at Risk 314 A. Acheson Composting Smell CA&ENV 106036 B. Hinson, GO GREEN 315 Delta Sustainability Issues CA&ENV 106075 Delta . CA&ENV 316 A. den Dikken Burns Bog Proposed Annual Meetings 106149 CC: LS T. Cooper, Executive Sewage Connection Fee and Plumbing 317 Director, Delta Hospital CP&D Permit for Forest for Our Future Project 106030 Foundation 318 C. Bayne Southlands CP&D 106072 .