Doctor Who NA50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macquarie University Researchonline

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author version of an article published as: Walsh, Robin. (1999). Journeys in time: digitising the past, exploring the future. LASIE, Vol. 30, No. 3, p. 35-44. Access to the published version: http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/77226/20071011-0000/www.sl.nsw.gov.au/lasie/sep99/sep99.pdf Copyright: State Library of New South Wales Abstract: Journeys in Time 1809-1822 is a major research initiative undertaken by Macquarie University Library to create an electronic archive of selected writings by Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie. It forms part of the Accessible Lifelong Learning (ALL) Project, a joint partnership between Macquarie University and the State Library of New South Wales. Journeys in Time is designed to provide scholarly access to primary source texts describing early colonial life in Australia. It also seeks to commemorate some of the tangible links between Macquarie University and its namesake, Lachlan Macquarie, the fifth governor of the colony of New South Wales (1810-1822). This article traces the development of the Journeys in Time project and explores some of the technical and design challenges that had to be met in the preparation of the transcripts and hypertext versions of the original documents. Journeys in Time: Digitising the Past, Exploring the Future... Robin Walsh. Manager, Library Design & Media Production Unit. Macquarie University Library NSW 2109. phone:(02)9850 7554 fax: (02) 9850 7513 email: [email protected] Introduction The Accessible Lifelong Learning (ALL) Project is a joint initiative of Macquarie University and the State Library of New South Wales to establish a ‘gateway’ web site for the provision of community-based information and lifelong learning opportunities. -

The Well-Mannered War (Doctor Who) Online

xgnae [Ebook pdf] The Well-Mannered War (Doctor Who) Online [xgnae.ebook] The Well-Mannered War (Doctor Who) Pdf Free Gareth Roberts, John Dorney DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1928858 in Books 2015-05-31Format: AudiobookOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 2 4.96 x .43 x 5.63l, .22 Binding: Audio CD | File size: 71.Mb Gareth Roberts, John Dorney : The Well-Mannered War (Doctor Who) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Well-Mannered War (Doctor Who): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Running out of storyBy Michael BattagliaBack in the day, Virgin had quite the line of Doctor Who books out. Not all of them were winners and some were rather mediocre (none were super-bad but I read some that came close) but it was nice to have someone publishing Who books on a more or less regular basis. And then, apparently out of nowhere, the BBC decided that they could do a better job and yanked the license away from Virgin, ending both the Missing Adventures line (which this particular book was part of) and the Seventh Doctor focused New Adventures line. You think that none of this is relevant? Well, I'm not finished yet. The last of the Missing Adventures features the fourth Doctor, Romana (the second one, played by Lalla Ward) and the ever-cheerful K-9. Still running from the Black Guardian (don't ask) they wind up on a planet near the end of Time and quickly get wrapped up in events. -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Cat's Cradle Time's Crucible by Marc Platt Doctor Who: Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible by Marc Platt

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Cat's Cradle Time's Crucible by Marc Platt Doctor Who: Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible by Marc Platt. THIS STORY TAKES. PLACE BETWEEN THE NOVEL "TIMEWYRM: THE BIG FINISH AUDIO. RECOMMENDED. OFFICIAL VIRGIN 'NEW. ADVENTURE' PAPERBACK. (ISBN 0-426-20365-8) RELEASED IN FEBRUARY. The TARDIS is invaded. by an alien presence. and destroyed. The. Ace finds herself in a. bizarre deserted city. ruled by A leech-like. monster known as the. Lost voyagers drawn. forTH from Ancient. Gallifrey perform. obsessive rituals. in the ruins. strands of time are. tangled in a cat�s. cradle of dimensions. Only the Doctor can. challenge the rule. of the Process and. restore the stolen. But the Doctor was. destroyed long ago, before Time began. As popular as Ghost Light was, truncated into three episodes with its exposition on the cutting room floor, Marc Platt�s atmospheric television serial never quite worked for me. With this novel, however, the written word allows Platt the freedom to tell his story at a slower pace, making it easier for the reader to follow not only the broad strokes but also the intricate subtleties of his plot. For me, the brilliance of Cat�s Cradle: Time�s Crucible can be summed up in just one word: Gallifrey. This novel is the first story since The Deadly Assassin to really get to grips with. the rudiments of Time Lord civilisation, and the first story ever to flesh out the culture of this fascinating race in any sort of satisfactory fashion. -

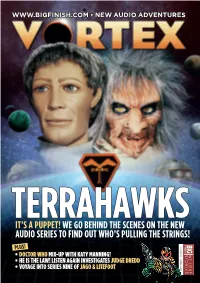

It's a Puppet! We Go Behind the Scenes on the New Audio Series to Find out Who's Pulling the Strings!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES TERRAHAWKS IT’S A PUPPET! WE GO BEHIND THE SCENES ON THE NEW AUDIO SERIES TO FIND OUT WHO’S PULLING THE STRINGS! PLUS! • APRIL 2015 74 ISSUE • DOCTOR WHO MIX-UP WITH KATY MANNING! • HE IS THE LAW! LISTEN AGAIN INVESTIGATES JUDGE DREDD • VOYAGE INTO SERIES NINE OF JAGO & LITEFOOT WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories. at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such bonus release, downloadable audio readings of as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the new short stories and discounts. Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The www.bigfinish.com Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. You can access a video guide to the site at We publish a growing number of books (non- www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX MAGAZINE PAGE 3 Sneak Previews & Whispers Editorial Charlotte Pollard: Series Two ASSUME that the majority of Big I Finish listeners are fans of cult TV and film and many of their friends Executive producer and writer share the same interest. -

The Bernice Summerfield Stories

www.BIGFINISH.COM • NE w AUDIO ADVENTURES THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE FREE! THE PHILIP OLIVIER AND AMY PEMBERTON TELL US ABOUT SHARING A TARDIS! PLUS! VORTEX ISSUE 43 n September 2012 BENNY GETS BACK TO HER ROOTS IN A NEW BOX SET BERNICE SUMMERFIELD: LEGION WRITER DONALD TOSH ON HIS 1960s LOST STORY FOURTHE ROSEMARINERS COMPANIONS EDITORIAL Listen, just wanted to remind you about the Doctor Who Special Releases. What do you mean, you haven’t heard of them? SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS It’s a special bundle of low-priced but excessively exciting new releases. The package consists of two box sets: Doctor Who: Dark Lalla Ward, Louise Jameson and Eyes (featuring the Eighth Doctor and the Daleks), UNIT: Dominion Seán Carlsen return to studio later (featuring the Seventh Doctor and Klein). PLUS! Doctor Who: Love and this month to begin recording the War (featuring the Seventh Doctor and Bernice Summerfield). PLUS! final series of Gallifrey audio dramas Two amazing adventures for the Sixth Doctor with Jago and Litefoot for 2013. (yes, I know!), Doctor Who: Voyage to Venus and Doctor Who: Voyage Last time we heard them, Romana, to the New World. Leela and Narvin were traversing the multiverse (with K-9 and Braxiatel Now, here’s the thing: this package is an experiment in cheaper still in tow). Now they’re stranded pricing. Giving you even more value for money. If it works and it on a barbaric Gallifrey that never attracts more people to listen – and persuades any of you illegal discovered time travel… and they’re downloaders out there – then it’s a model for pricing that we will looking for an escape. -

Connotations Volume 19 Issue 01

Volume 19, Issue 4 August / September 2009 ConNotations FREE The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society A Conversation with Featured Inside Paul Cornell Regular Features Special Features by Lee Whiteside SF Tube Talk An Conversation with All the latest news about Paul Cornell This issue, we’re talking with Paul Scienc Fiction TV shows by Lee Whiteside Cornell, writer of the Doctor Who by Lee Whiteside episodes Father’s Day, Human Hokey Smoke! Nature, and The Family of Blood, Gamers Corner It’s the very nearly 50th recent novel “British Summertime” New and Reviews from Anniversary of Rocky the Flying and writer for several current and the gaming world Squirrel and Bullwinkle J. Moose upcoming series for Marvel Comics. By Shane Shellenbarger Videophile & Around the Dial Reviews of genre releases An Amercan in New Zealand Lee: Some people may see you as an on DVD and current TV shows by Jeffrey Lu overnight sensation, you’ve gotten a lot of acclaim for the Captain Britain Screening Room Kinuko C. Craft – comic and your Doctor Who episodes Reviews of current theatrical releases An Appreciation of Cover Art have been well received. You’ve by Chris Paige actually been writing TV and novels Musical Notes for how many years now? The latest news of Filk and Filkers Plus Paul: Let’s see, I think 1990, was my first professional sale, so we’re Pre-Con News CASFS Business Report coming up on 20 years. Tidbits about upcoming conventions FYI ConClusion News and tidbits of interest to fans L: What was your first sale? © Lee Whiteside News and Reviews P: I won a BBC writing competition of Genre conventions Club Listings and got a short science fiction play on P: I think it was seven across the New BBC 2 just about the same time I started In Our Book and Missing line. -

THE MENTOR 85 “The Magazine Ahead of Its Time”

THE MENTOR 85 “The Magazine Ahead of its Time” JANUARY 1995 page 1 stepped in. When we stepped out at the Second floor we found three others, including Pauline Scarf, already waiting in the room. The other THE EDITORIAL SLANT lift hadn’t arrived. I took off my coat, unpacked my bags of tea-bags, coffee, sugar, cups, biscuits, FSS info sheets and other junk materials I had brought, then set about, with the others, setting up the room. At that point those from the other lift arrived - coming down in the second lift. by Ron Clarke They had overloaded the first lift. However the FSS Information Officer was not with them - Anne descended five minutes later in another lift. After helping set up the chairs in the room in a circle, I gave a quick run- down on the topic of discussion for the night - “Humour In SF” and asked who wanted to start. After a short dead silence, I read out short items from the Humour In SF section from the ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION and the meeting got into first gear. The meeting then There used to be a Futurian Society in New York. There used discussed what each attendee thought of humour in SF and gave to be a Futurian Society in Sydney. The New York Futurian Society is comments on the books they had brought illustrating their thoughts or long gone - the Futurian Society of Sydney lives again. what they had read. Those attending the meeting were Mark When I placed the advertisements in 9 TO 5 Magazine, gave Phillips, Graham Stone, Ian Woolf, Peter Eisler, Isaac Isgro, Wayne pamphlets to Kevin Dillon to place in bookshops and puts ads in Turner, Pauline Scarf, Ken Macaulay, Kevin Dillon, Anne Stewart, Gary GALAXY bookshop I wasn’t sure how many sf readers would turn up Luckman and myself. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

1614727366480.Pdf

More Ultramarines from Black Library • THE CHRONICLES OF URIEL VENTRIS • BOOK 1: NIGHTBRINGER BOOK 2: WARRIORS OF ULTRAMAR BOOK 3: DEAD SKY, BLACK SUN BOOK 4: THE KILLING GROUND BOOK 5: COURAGE AND HONOUR BOOK 6: THE CHAPTER’S DUE Graham McNeill • DAWN OF FIRE • BOOK 1: AVENGING SON Guy Haley BOOK 2: THE GATE OF BONES Andy Clark INDOMITUS Gav Thorpe • DARK IMPERIUM • BOOK 1: DARK IMPERIUM BOOK 2: PLAGUE WAR Guy Haley OF HONOUR AND IRON Ian St. Martin KNIGHTS OF MACRAGGE Nick Kyme DAMNOS Nick Kyme VEIL OF DARKNESS An audio drama Nick Kyme BLOOD OF IAX Robbie MacNiven CONTENTS Cover Backlist Title Page Warhammer 40,000 Book I 1 2 3 4 Book II 5 6 7 8 Book III 9 10 11 12 13 Epilogue About the Author An Extract from ‘Dawn of Fire: Avenging Son’ A Black Library Publication eBook license For more than a hundred centuries the Emperor has sat immobile on the Golden Throne of Earth. He is the Master of Mankind. By the might of His inexhaustible armies a million worlds stand against the dark. Yet, He is a rotting carcass, the Carrion Lord of the Imperium held in life by marvels from the Dark Age of Technology and the thousand souls sacrificed each day so that His may continue to burn. To be a man in such times is to be one amongst untold billions. It is to live in the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable. It is to suffer an eternity of carnage and slaughter. It is to have cries of anguish and sorrow drowned by the thirsting laughter of dark gods. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Jago & Litefoot

ISSUE 37 • MARCH 2012 NOT FOR RESALE FREE! SWEET SEVATEEM LOUISE JAMESON ON TOM BAKER AND RUNNING DOWN CORRIDORS DARK SHADOWS WHAT’S COMING UP FOR THE RESIDENTS OF COLLINWOOD JAGO & LITEFOOT THE INVESTIGATORS OF INFERNAL INCIDENTS RETURN FOR A FOURTH SERIES! EDITORIAL SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS ell, there I was last month, pondering about the intricacies of the public side W of being an executive producer at Big Finish (and by the way, thanks to those of you who wrote expressing your considered support), when suddenly I get to enjoy the luxurious side of it all. Yes, I’m not just talking luxury in an LA hotel at the Gallifrey One convention – I’m talking luxury at Barking Abbey School and Big Finish Day 2! Okay, perhaps not so much luxury at Barking Abbey School as reminders of my old junior ig Finish’s first original Blake’s 7 school days, when we used to paint hands and novel The Forgotten is a rollickingly arms green during art lessons and pretend we B great adventure story set during had the Silurian plague. Not that I actually went series one, which leads into the TV story to Barking Abbey School, but that venerable Breakdown. Blake and his crew on the institution is of an architectural style much Liberator are being mercilessly hunted by copied in the UK, sometime during the Middle Travis and his pursuit ships, and the path of Ages, I believe. I love quadrangles, don’t you? escape actually leads to something far They conjure up the smells of sour milk (before more dangerous… Mrs Thatcher valiantly put paid to that!) and Writers Cavan Scott and Mark Wright, urinals with gigantic disinfectant blocks, which who created The Forge for the Doctor Who teachers sternly forbade us to crush with our main range, work to Blake’s 7’s strengths, cheap slip-on shoes.