Chapter 1 Lionel Tertis and Ralph Vaughan Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Desert Island Times 18

D E S E RT I S L A N D T I M E S S h a r i n g f e l l o w s h i p i n NEWPORT SE WALES U3A No.18 17th July 2020 Commercial Street, c1965 A miscellany of Contributions from OUR members 1 U3A Bake Off by Mike Brown Having more time on my hands recently I thought, as well as baking bread, I would add cake-making to my C.V. Here is a Bara Brith type recipe that is so simple to make and it's so much my type of cake that I don't think I'll bother buying one again. (And the quantities to use are in 'old money'!!) "CUP OF TEA CAKE" Ingredients 8oz mixed fruit Half a pint of cooled strong tea Handful of dried mixed peel 8oz self-raising flour # 4oz granulated sugar 1 small egg # Tesco only had wholemeal SR flour (not to be confused � with self-isolating flour - spell checker problem there! which of course means "No Flour At All!”) but the wholemeal only enhanced the taste and made it quite rustic. In a large bowl mix together the mixed fruit, mixed peel and sugar. Pour over the tea, cover and leave overnight to soak in the fridge. Next day preheat oven to 160°C/145°C fan/Gas Mark 4. Stir the mixture thoroughly before adding the flour a bit at a time, then mix in the beaten egg and stir well. Grease a 2lb/7" loaf tin and pour in the mixture. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright ALFRED HILL’S VIOLA CONCERTO: ANALYSIS, COMPOSITIONAL STYLE AND PERFORMANCE AESTHETIC Charlotte Fetherston A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, NSW 2014 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

Great Violinists • Kreisler 8.111406

ADD Great Violinists • Kreisler 8.111406 THE COMPLETE recordinGs • 7 BACH BEETHOVEN KoŽeLUcH WAGNER dVořáK KreisLer Fritz Kreisler Recorded 1921-1925 Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962): Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894): Leopold Antonín Koželuch (1747-1818) Deux Mélodies, Op. 3 (att. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)): The complete recordings • 7 ^ No. 1: Moderato assai in F major 2:50 La ritrovata figlia di ottone ii rec. 1st November 1923; ™ Gavotte in F, (arr. A. Walter Kramer) 2:54 mat. Bb-3779; Victor 1039 rec. 29th August 1925; Acoustic Recordings Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): mat. BVE-31975-4; Victor 1136 HMV Acoustic Recordings 8 Andante favori in F, Woo 57 (arr. Kreisler) 3:08 Jean Gabriel Prosper Marie (1852-1928): & (Hayes, Middlesex, 1921-24) rec. 23rd September 1924; La Cinquantaine (The Golden Wedding) 2:50 Johann sebastian Bach (1685-1750) mat. Bb-3778-7; Victor 3037 rec. 1st November 1923; Wilhelm Jeral (1861-1935): Anna Magdalena notebook 1 Sérénade viennoise, Op. 18 3:19 Robert Schumann (1810-1856): mat. Bb-3781; Victor 1039 £ Minuet in G, BWV Anh. 116 rec. 16th December 1921; Klavierstücke, op. 85 (doubtful attribution, arr. Winternitz) 2:53 mat. Bb-779-3; Victor 87579 9 No. 12 Abendlied (arr. Svendsen) 2:18 Electrical Recordings rec. 29th August 1925; rec. 23rd September 1924; Victor Talking Machine company mat. BVE-31940-12; Victor 1136 Traditional: mat. Bb-5102-6; Victor 3036 (new York, 1925-26) 2 Londonderry Air (arr. Kreisler) 3:20 sigmund romberg (1887-1951) rec. 17th December 1921; Fritz Kreisler: Fritz Kreisler: The Student Prince – Operetta ¢ mat. Bb-780-5; Victor 87577 Apple Blossoms – Operetta * Paraphrase on two russian folk songs 3:09 Deep in my heart, dear (arr. -

Lionel Tertis's One-Man Victory

— í —_ -, ------ —------------------------------- 1 MUSIC MARTIN COOPER I THE NAMING of the bowed string instruments in com mon use today is confusing Lionel Tertis’s because it is illogical. All belong by origin to the viol family whose many members played a leading role in Euro pean music of the 15th, 16th one-man victory and 17th centuries and sur vived well into the 18th. Like many old families, the For a number of reasons, Concertante for violin and viola viols were eventually ousted by partly historical and partly con K. 364 and Berlioz’s “ Harold in a closely related cadet branch, nected with the actual register Italy ” the solo repertory of which rose during the 17t'h cen of the instrument, the viola and the viola was simply non-exis tury and had largely taken over the double bass have had the tent and Tertis was obliged the role of the older branch by most uneventful history of the to rely on arrangements of his 1750. This still flourishes today four. The viola’s part has cor own. He has over the yeais under the names of violin, viola, responded to that of the alto in made some forty of these, rang violoncello, and “ double bass,” a vocal quartet, essentially a ing from “The Londonderry whose names clearly reveal middle voice more devoted to Air” to concertos by Bach, their origin, however misleading filling in the harmony or even Mozart, Haydn, Delius and they may be in other respects. doubling the lines of its neigh Elgar and sonatas by Handel, Like many upstarts at the be bours above and below; and for Beethoven and Brahms. -

Sacred Song Sisters: Choral and Solo Vocal Church Music by Women Composers for the Lenten Revised Common Lectionary

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2020 Sacred Song Sisters: Choral and Solo Vocal Church Music by Women Composers for the Lenten Revised Common Lectionary Lisa Elliott Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Composition Commons, and the Other Music Commons Repository Citation Elliott, Lisa, "Sacred Song Sisters: Choral and Solo Vocal Church Music by Women Composers for the Lenten Revised Common Lectionary" (2020). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3889. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/19412066 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SACRED SONG SISTERS: CHORAL AND SOLO VOCAL CHURCH MUSIC BY WOMEN COMPOSERS FOR THE LENTEN REVISED COMMON LECTIONARY By Lisa A. Elliott Bachelor of Arts-Music Scripps College 1990 Master of Music-Vocal Performance San Diego State University 1994 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2020 Copyright 2020 Lisa A. -

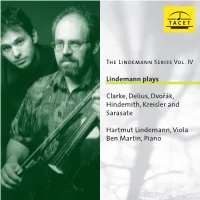

Lindemann Plays Clarke, Delius, Dvorák, Hindemith

CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ Booklet T 095 Seite 32 CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ Booklet T 095 Seite 1 COVER Rebecca Clarke (1886 – 1979) Sonata for viola and piano (1919) 23'18 1 Impetuoso 7'51 2 Vivace 4'02 3 Adagio – Allegro 11'25 Paul Hindemith (1895 – 1963) Sonate für Viola und Klavier op.11, Nr. 4 17'42 4 Fantasie. Ruhig 3'21 The Lindemann Series Vol. IV 5 Thema mit Variationen. Ruhig und einfach 4'39 6 Finale (mit Variationen). Sehr lebhaft 9'42 Lindemann plays Fritz Kreisler (1875 – 1962) 7 Sicilienne et Rigaudon im Stile von Francoeur 4'43 Clarke, Delius, Dvorák,ˇ Hindemith, Kreisler and Antonin Dvorákˇ (1841 – 1904) / Fritz Kreisler Sarasate Slawischer Tanz Nr. 2 8 Andante grazioso quasi Allegretto 5'04 Hartmut Lindemann, Viola Pablo de Sarasate (1844 – 1908) Ben Martin, Piano Zigeunerweisen 9 Moderato – Allegro molto vivace 8'58 Frederick Delius (1862 – 1934) / Arr.: Lionel Tertis Serenade aus »Hassan« 5 bl 3'27 9 Con moto moderato T E C A Hartmut Lindemann, Viola · Ben Martin, Piano T CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ TS Tonträger CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ TS Tonträger A Nice Old-fashioned Programme granted the blessing of loving a woman as nata to Berkshire and Pittsfield. In the first much as he loved her. Clarke and Friskin, now round ten compositions were chosen out of a Foreword Stanford (who also advised her to switch to the both 58 years old, married on Saturday the total of 73 which had been sent in. In the sec- He wanted to put together a “nice old-fash- viola) and counterpoint under Sir Frank Bridge; 23 rd September 1944 in New York. -

The Music of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935): a Critical Study

The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and infomation derived from it should be acknowledged. The Music of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935): A Critical Study Duncan James Barker A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Music Department University of Durham 1999 Volume 2 of 2 23 AUG 1999 Contents Volume 2 Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline 246 Appendix 2: The Mackenzie Family Tree 257 Appendix 3: A Catalogue of Works 260 by Alexander Campbell Mackenzie List of Manuscript Sources 396 Bibliography 399 Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline NOTE: The following timeline, detailing the main biographical events of Mackenzie's life, has been constructed from the composer's autobiography, A Musician's Narrative, and various interviews published during his lifetime. It has been verified with reference to information found in The Musical Times and other similar sources. Although not fully comprehensive, the timeline should provide the reader with a useful chronological survey of Mackenzie's career as a musician and composer. ABBREVIATIONS: ACM Alexander Campbell Mackenzie MT The Musical Times RAM Royal Academy of Music 1847 Born 22 August, 22 Nelson Street, Edinburgh. 1856 ACM travels to London with his father and the orchestra of the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, and visits the Crystal Palace and the Thames Tunnel. 1857 Alexander Mackenzie admits to ill health and plans for ACM's education (July). ACM and his father travel to Germany in August: Edinburgh to Hamburg (by boat), then to Hildesheim (by rail) and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (by Schnellpost). -

Ana Alves MMIA 2017.Pdf

Resumo Esta dissertação de mestrado tem como objetivo estudar a influência do violetista Lionel Tertis (1876-1975) no florescimento do reportório para viola d’arco no séc. XX. É apresentada uma breve contextualização biográfica do músico inglês na qual são evidenciados alguns aspetos da sua vida relacionados com o aparecimento de obras marcantes, tanto para a sua carreira musical, como para o reportório do instrumento. O trabalho de análise, seleção, compilação e organização de um conjunto de dados obtidos, essencialmente, em fontes secundárias, deu origem à elaboração de um catálogo de 122 obras para viola d’arco que guardam uma relação direta com Lionel Tertis: seja por terem sido compostas ou transcritas por ele, por lhe terem sido dedicadas, por ter sido ele a encomendá- las e/ou por ter sido ele a estreá-las. Palavras-chave Lionel Tertis; catálogo; reportório; viola de arco; Inglaterra; séc. XX iii A Influência de Lionel Tertis no florescimento do reportório para viola d’arco em Inglaterra no séc. XX: uma proposta de catalogação Abtract The present master’s dissertation consists in understand the influence of Lionel Tertis (1876-1975) on the emergence of the repertory for viola on the twentieth century. A brief biografical context of the english musician is presented where some aspects of his life connected with the appearance of outstanding works are shown up, either for his musical career as well as for the repertoire of the instrument. The analysis, selection, compilation and organization of the information, essentially obtained in secondary sources, provided the creation of a catalog with 122 works for viola, which has a straight relation with Lionel Tertis: either by being composed or transcribed by him, dedicated to him, ordered by him and/or because he had made them debut.