Connecticut Government and Politics an Introduction Also by Gary L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VLB) : DANNEL MALLOY, ET AL., : Defendants

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT RANDALL PEACOCK, : Plaintiff, : : v. : Case No. 3:18cv406 (VLB) : DANNEL MALLOY, ET AL., : Defendants. : RULING AND ORDER Plaintiff Randall Peacock was confined at Brooklyn Correctional Institution when he initiated this civil rights action. He has filed an amended complaint naming Governor Ned Lamont, Lieutenant Governor Susan Bysiewicz, Attorney General William Tong, Commissioner of Correction Rollin Cook, Chief State’s Attorney Kevin T. Kane, Director of Parole and Community Services Joseph Haggan, Chairman of the Board of Pardons and Paroles Carleton J. Giles and Special Management Unit Parole Officer Frank Mirto as defendants. See Am. Compl., Doc. No. 14. On November 20, 2019 and December 31, 2019, Plaintiff filed exhibits to supplement the amended complaint. See Doc. Nos. 16, 17. On April 13, 2020, Plaintiff filed a motion for leave to file a second amended complaint. See Mot. Amend, Doc. No. 16. For the reasons set forth below, the court will deny the motion to amend and dismiss the first amended complaint. I. Motion for Leave to Amend [Doc. No. 18] Plaintiff seeks leave to file a second amended complaint to add a claim regarding a parole hearing that occurred on January 31, 2020. See Mot. Amend at 1-2. Peacock alleges that during the hearing, a panel of three members of the Board of Pardons and Paroles voted him to be released on parole on or after February 29, 2020. See id.; Ex., Doc. No. 18-1. As of April 13, 2020, he had not been released on parole. See Mot. Amend. at 2. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

AUDIENCE of the FEAST of the FULL MOON 22 February 2016 – 13 Adar 1 5776 23 February 2016 – 14 Adar 1 5776 24 February 2016 – 15 Adar 1 5776

AUDIENCE OF THE FEAST OF THE FULL MOON 22 February 2016 – 13 Adar 1 5776 23 February 2016 – 14 Adar 1 5776 24 February 2016 – 15 Adar 1 5776 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ As a point of understanding never mentioned before in any Akurian Lessons or Scripts and for those who read these presents: When The Most High, Himself, and anyone else in The Great Presence speaks, there is massive vision for all, without exception, in addition to the voices that there cannot be any misunderstanding of any kind by anybody for any reason. It is never a situation where a select sees one vision and another sees anything else even in the slightest detail. That would be a deliberate deception, and The Most High will not tolerate anything false that is not identified as such in His Presence. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Encamped and Headquartered in full array at Philun, 216th Realm, 4,881st Abstract, we received Call to present ourselves before The Most High, ALIHA ASUR HIGH, in accordance with standing alert. In presence with fellow Horsemen Immanuel, Horus and Hammerlin and our respective Seconds, I requested all available Seniors or their respective Seconds to attend in escort. We presented ourselves in proper station and I announced our Company to The Most High in Grand Salute as is the procedure. NOTE: Bold-italics indicate emphasis: In the Script of The Most High, by His direction; in any other, emphasis is mine. The Most High spoke: ""Lord King of Israel El Aku ALIHA ASUR HIGH, Son of David, Son of Fire, you that is Named of My Own Name, know that I am pleased with your Company even unto the farthest of them on station in the Great Distances. -

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State?

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State? A Thesis Presented to The Division of History and Social Sciences Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Daniel Krantz Toffey May 2007 Approved for the Division (Political Science) Paul Gronke Acknowledgements Acknowledgements make me a bit uneasy, considering that nothing is done in isolation, and that there are no doubt dozens—perhaps hundreds—of people responsible for instilling within me the capability and fortitude to complete this thesis. Nonetheless, there are a few people that stand out as having a direct and substantial impact, and those few deserve to be acknowledged. First and foremost, I thank my parents for giving me the incredible opportunity to attend Reed, even in the face of staggering tuition, and an uncertain future—your generosity knows no bounds (I think this thesis comes out to about $1,000 a page.) I’d also like to thank my academic and thesis advisor, Paul Gronke, for orienting me towards new horizons of academic inquiry, and for the occasional swift kick in the pants when I needed it. In addition, my first reader, Tamara Metz was responsible for pulling my head out of the data, and helping me to consider the “big picture” of what I was attempting to accomplish. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Charles McKinley Fund for providing access to the Cooperative Congressional Elections Study, which added considerable depth to my analyses, and to the Fautz-Ducey Public Policy fellowship, which made possible the opportunity that inspired this work. -

150Th Anniversary

Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society 2011 Vol. XXIII, No. 1 www.CTIAHS.com Civil War 150th Anniversary Sentry at St. Bernard’s stands watch over resting place of Irish comrades he graves of Connecticut Irish- than 300 Civil War veterans are buried T American patriots can be found at there. Civil War battlefields from Bull Run, Va., Ironically, the monument was dedi- to New Orleans, La., and from Antietam, cated on the very same day, Oct. 28, 1886, Md., to Gettysburg, Pa. But in New Ha- that another great memorial of Irish- ven, Ct., there is an almost forgotten American immigration, the Statue of Lib- cemetery, St. Bernard’s, in which there erty, was dedicated in New York harbor. probably are more Connecticut Irish sol- Later this summer, our CIAHS will diers from that war interred than any in sponsor a special memorial program at St. any other single place. Bernard’s Cemetery as part of the state- So many, in fact, that in 1886 the state wide and nationwide observance of the of Connecticut appropriated $3,000 for 150th anniversary of the Civil War, which construction of a monument to their mem- began with the attack on Fort Sumter in ory. Lists published at that time, 20 years Charleston, S.C., harbor in April 1861. after the war, indicated that by then, well The 1886 dedication of the monument before the passing of the Civil War gen- at St. Bernard’s — pronounced with the eration, more than 150 Civil War veterans accent on the second syllable by New had been interred there. -

To Download This Handout As an Adobe Acrobat

AEI Election Watch 2006 October 11, 2006 Bush’s Ratings Congress’s Ratings Approve Disapprove Approve Disapprove CNN/ORC Oct. 6-8 39 56 CNN/ORC Oct. 6-8 28 63 Gallup/USAT Oct. 6-8 37 59 Gallup/USAT Oct. 6-8 24 68 ABC/WP Oct. 5-8 39 60 ABC/WP Oct. 5-8 32 66 CBS/NYT Oct. 5-8 34 60 CBS/NYT Oct. 5-8 27 64 Newsweek Oct. 5-6 33 59 Time/SRBI Oct. 3-4 31 57 Time/SRBI Oct. 3-4 36 57 AP/Ipsos Oct. 2-4 27 69 AP/Ipsos Oct. 2-4 38 59 Diag.-Hotline Sep. 24-26 28 65 PSRA/Pew Sep. 21-Oct. 4 37 53 LAT/Bloom Sep. 16-19 30 57 NBC/WSJ Sep. 30-Oct. 2 39 56 Fox/OD Sep. 12-13 29 53 Fox/OD Sep. 26-27 42 54 NBC/WSJ (RV) Sep. 8-11 20 65 Diag-Hotline Sep. 24-26 42 56 LAT/Bloom Sep. 16-19 45 52 Final October approval rating for the president and Final October approval rating for Congress and number of House seats won/lost by the president’s number of House seats won/lost by the president’s party party Gallup/CNN/USA Today Gallup/CNN/USA Today Number Number Approve of seats Approve of seats Oct. 2002 67 +8 Oct. 2002 50 +8 Oct. 1998 65 +5 Oct. 1998 44 +5 Oct. 1994 48 -52 Oct. 1994 23 -52 Oct. 1990 48 -9 Oct. 1990 24 -9 Oct. 1986 62 -5 Apr. -

CONNECTICUT's BROKEN CITIES: Laying the Conditions for Growth In

CONNECTICUT’S BROKEN CITIES: Laying the conditions for growth in poor urban communities By Stephen D. Eide Senior Fellow, Manhattan Institute JANUARY 2017 Letter from the Yankee Institute For too long, some of Connecticut’s largest cities have languished. Not only do their residents suffer from high rates of poverty and crime, the cities have also endured periods of serious fiscal insecurity. Everyone in Connecticut has an interest in seeing our urban areas revitalized, but the reasons for the cities’ struggles – and therefore the solutions to them – are under dispute. Although many attribute urban challenges to insufficient tax revenues, this report demonstrates that there are significant problems with how city leaders have chosen to spend taxpayer dollars – particularly when it comes to employee retirement benefits. This report – produced in partnership with Manhattan Institute for Policy Research – is especially timely given that the city of Hartford will likely face bankruptcy unless the state intervenes in the coming months. That is why the solutions offered here by author Stephen Eide are so important: If state lawmakers treat Hartford’s problems as though they merely stem from a lack of revenue, the city will continue to struggle to achieve long-term fiscal health. But if the issues identified in this report are acknowledged and addressed responsibly by both local and state leaders -- for example, by reforming binding arbitration laws - it will help every Connecticut municipality achieve greater fiscal stability. www.YankeeInstitute.org • Second, their mill rates rank among the highest I. Executive Summary in the state, and have been rising in recent years. -

Freemasonry: the Gift That Gives Wallingford, CT 06492 P.O

Connecticut FREEMASONS DeCeMBeR 2012 Freemasonry: The Gift That Gives Wallingford, CT 06492 CT Wallingford, Box 250 P.O. 69 Masonic Avenue Grand Lodge of Connecticut, AF & AM page 5 page 18 page 23 Jonathan Glassman Master Mason Iconic Columns Receives Degree in Replaced at Beard Award Washington’s Room Washington Lodge TABLe OF CONTeNTS Connecticut FREEMASONS Relief from Hurricane Sandy ..................................................3 News from the Valley of Hartford ........................................15 Grand Master’s Message ..........................................................4 Quality of Life Purchases New Organ ..................................15 Volume 8 - Number 7 Jonathan Glassman Receives Beard Award ............................5 Commandery and DeMolay Explore Swords ......................16 Publisher Grand Chaplain’s Pulpit .........................................................6 Raised in Washington’s Room ..............................................18 The Grand LodGe Landmarks Committee Address .............................................6 Masonic Vice-Presidents of the United States .....................19 of ConnectiCuT AF & aM Masonicare Experience ...........................................................7 Welcome/Congratulations ....................................................20 Grand Historian’s Corner .......................................................8 Moriah Lodge Fills the Halls ................................................ 21 Editor-in-Chief Autumn Gathering Honors Veterans ......................................8 -

A Dan Livingston Biography

A Dan Livingston Biography Dan Livingston is an attorney who has been a labor and progressive activist in three states – New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. A life-time member of the United Auto Workers Union, Dan is the product of the marriage of a Union President, and a Social Worker, who boasts of being on picket lines before he could walk. Dan worked for two years as a Union organizer before entering Yale Law School in 1979. He graduated in 1982, and has since been admitted to the Connecticut and Federal district court bars, as well as the to the bar of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court. Dan has been a member of the Firm for 35 years and has been a partner since 1984. He has extensive experience in labor and employment law including arbitrations, and litigation before the State Labor Relations Board, the National Labor Relations Board, the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights & Opportunities, the Connecticut Superior Court, the U.S. District Court, the Connecticut Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. He has represented hundreds of individuals in [email protected] discrimination, harassment, and wrongful termination cases against their 860-570-4625 employers. Dan also serves as chief negotiator in contract negotiations, and lead advocate in interest arbitrations, including the successful effort of State Employee Unions to secure health and pension benefits for domestic partners of the state's gay and lesbian employees when Connecticut law refused to allow same-sex marriage. Dan has been the Chief Negotiator for SEBAC, the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition since 1994. -

Transcending Political Party Constraints: an Ideographic

TRANSCENDING POLITICAL PARTY CONSTRAINTS: AN IDEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE RHETORIC OF CHARLIE CRIST AND JOE LIEBERMAN AS INDEPENDENT CANDIDATES by Cara Poplak A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wished to express her sincere thanks and love to her parents and family for their support and encouragement throughout the writing of this manuscript. The author is grateful to her advisors at Florida Atlantic for their continuous guidance and assistance in the completion of this manuscript. ii ABSTRACT Author: Cara Poplak Title: Transcending Political Party Constraints: An Ideographic Analysis of the Rhetoric of Charlie Crist and Joe Lieberman as Independent Candidates Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Becky Mulvaney Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2011 This thesis analyzes how the American political system presents specific rhetorical constraints for independent and third party candidates who are ―othered‖ by the system. To better understand how independent candidates overcome these constraints, the rhetoric of two such recent candidates, Charlie Crist and Joe Lieberman, is analyzed using ideographic criticism. These two candidates were originally affiliated with one of the two major political parties, but changed their party affiliation to run as Independent candidates. To facilitate their transition to independent candidates, both politicians used popular American political ideographs such as ―the people,‖ ―freedom,‖ and ―unity‖ to maintain their allegiance to America and their constituencies, while separating their political ideology from their prior party affiliation. -

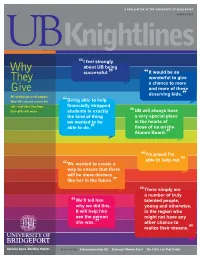

Spring 2014 a Publication of the University of Bridgeport

UB KNIGHTLINES SPRING 2014 A PUBLICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF BRIDGEPORT SPRING 2014 “ I feel strongly about UB being Why successful.” “ It would be so wonderful to give They a chance to more Give and more of these deserving kids. All institutions need support. ” Why UB’s donors answer the “ Being able to help call—and what they hope their gifts will mean. students is exactly “ UB will always have the kind of thing a very special place we wanted to be in the hearts of able to do.” those of us on the Alumni Board.” “ I’m proud I’m able to help out.” “ We wanted to create a way to ensure that there will be more doctors like her in the future.” “ There simply are a number of truly “ We’ll tell him talented people, why we did this. young and otherwise, It will help him in the region who see the person might not have any she was.” other chance to realize their dreams.” ALSO INSIDE Entrepreneurship 101 t Strongest Woman Ever! t The Little Lab That Could 1 UB KNIGHTLINES SPRING 2014 President’s Line There’s been quite a bit of talk about entrepreneurship lately. Pioneers from Steve Jobs to Mark Zuckerberg have changed the way we live and work. As the president of a university with a mission to prepare students to excel in the professional world, I’ve also witnessed how entrepreneurs are inspiring today’s students. But while entrepreneurship may be a hot topic on today’s college campuses, it’s certainly not a new concept. -

Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission 999 E Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20463 Re: Peckinpaugh for Congress P

Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission 999 E Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20463 Re: Peckinpaugh for Congress P.O. Box 615 Essex, CT 06426 FEC Committee ID #: C00482885 To Whom It May Concern: My name is Nancy DiNardo. My address is 330 Main Street, Hartford, CT 06106. I am filing this complaint in my official capacity as Chairwoman of the Connecticut Democratic Party, located at 330 Main Street, Hartford, CT 06106. The information in this complaint are taken from FEC filings (Form F3N) by Peckinpaugh for Congress, P.O. Box 615, Essex, CT 06426, FEC Committee ID #C00482885. The Committee was formed for a House race in 2010 for the Second Congressional District in Connecticut. The candidate, Janet Peckinpaugh, was a Republican who lost the race. In three of the five reports filed between the July 14, 2010 Quarterly Report up to and including the December 1, 2010 Post-General Report, there were a series of disbursements without any explanation included in the FEC Reports. Overall, the campaign disbursements totaled $269,624.74. Of these campaign disbursements, nearly 25% – or $68,090.57 – went unexplained. The candidate herself was paid a total of $10,921.82 in disbursements. Of these candidate disbursements, nearly 74% – or $8,051.21 – went unexplained. In reviewing the unexplained disbursements in the context of the overall disbursements, it appears that the Committee was aware of the need for explanations, as the first two Reports contained an explanation for each disbursement. The final Report, filed December 1, 2010 and covering the period from October 14, 2010 through November 22, 2010, failed to explain 36 of the 53 disbursements.