CONNECTICUT's BROKEN CITIES: Laying the Conditions for Growth In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VLB) : DANNEL MALLOY, ET AL., : Defendants

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT RANDALL PEACOCK, : Plaintiff, : : v. : Case No. 3:18cv406 (VLB) : DANNEL MALLOY, ET AL., : Defendants. : RULING AND ORDER Plaintiff Randall Peacock was confined at Brooklyn Correctional Institution when he initiated this civil rights action. He has filed an amended complaint naming Governor Ned Lamont, Lieutenant Governor Susan Bysiewicz, Attorney General William Tong, Commissioner of Correction Rollin Cook, Chief State’s Attorney Kevin T. Kane, Director of Parole and Community Services Joseph Haggan, Chairman of the Board of Pardons and Paroles Carleton J. Giles and Special Management Unit Parole Officer Frank Mirto as defendants. See Am. Compl., Doc. No. 14. On November 20, 2019 and December 31, 2019, Plaintiff filed exhibits to supplement the amended complaint. See Doc. Nos. 16, 17. On April 13, 2020, Plaintiff filed a motion for leave to file a second amended complaint. See Mot. Amend, Doc. No. 16. For the reasons set forth below, the court will deny the motion to amend and dismiss the first amended complaint. I. Motion for Leave to Amend [Doc. No. 18] Plaintiff seeks leave to file a second amended complaint to add a claim regarding a parole hearing that occurred on January 31, 2020. See Mot. Amend at 1-2. Peacock alleges that during the hearing, a panel of three members of the Board of Pardons and Paroles voted him to be released on parole on or after February 29, 2020. See id.; Ex., Doc. No. 18-1. As of April 13, 2020, he had not been released on parole. See Mot. Amend. at 2. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

150Th Anniversary

Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society 2011 Vol. XXIII, No. 1 www.CTIAHS.com Civil War 150th Anniversary Sentry at St. Bernard’s stands watch over resting place of Irish comrades he graves of Connecticut Irish- than 300 Civil War veterans are buried T American patriots can be found at there. Civil War battlefields from Bull Run, Va., Ironically, the monument was dedi- to New Orleans, La., and from Antietam, cated on the very same day, Oct. 28, 1886, Md., to Gettysburg, Pa. But in New Ha- that another great memorial of Irish- ven, Ct., there is an almost forgotten American immigration, the Statue of Lib- cemetery, St. Bernard’s, in which there erty, was dedicated in New York harbor. probably are more Connecticut Irish sol- Later this summer, our CIAHS will diers from that war interred than any in sponsor a special memorial program at St. any other single place. Bernard’s Cemetery as part of the state- So many, in fact, that in 1886 the state wide and nationwide observance of the of Connecticut appropriated $3,000 for 150th anniversary of the Civil War, which construction of a monument to their mem- began with the attack on Fort Sumter in ory. Lists published at that time, 20 years Charleston, S.C., harbor in April 1861. after the war, indicated that by then, well The 1886 dedication of the monument before the passing of the Civil War gen- at St. Bernard’s — pronounced with the eration, more than 150 Civil War veterans accent on the second syllable by New had been interred there. -

Freemasonry: the Gift That Gives Wallingford, CT 06492 P.O

Connecticut FREEMASONS DeCeMBeR 2012 Freemasonry: The Gift That Gives Wallingford, CT 06492 CT Wallingford, Box 250 P.O. 69 Masonic Avenue Grand Lodge of Connecticut, AF & AM page 5 page 18 page 23 Jonathan Glassman Master Mason Iconic Columns Receives Degree in Replaced at Beard Award Washington’s Room Washington Lodge TABLe OF CONTeNTS Connecticut FREEMASONS Relief from Hurricane Sandy ..................................................3 News from the Valley of Hartford ........................................15 Grand Master’s Message ..........................................................4 Quality of Life Purchases New Organ ..................................15 Volume 8 - Number 7 Jonathan Glassman Receives Beard Award ............................5 Commandery and DeMolay Explore Swords ......................16 Publisher Grand Chaplain’s Pulpit .........................................................6 Raised in Washington’s Room ..............................................18 The Grand LodGe Landmarks Committee Address .............................................6 Masonic Vice-Presidents of the United States .....................19 of ConnectiCuT AF & aM Masonicare Experience ...........................................................7 Welcome/Congratulations ....................................................20 Grand Historian’s Corner .......................................................8 Moriah Lodge Fills the Halls ................................................ 21 Editor-in-Chief Autumn Gathering Honors Veterans ......................................8 -

A Dan Livingston Biography

A Dan Livingston Biography Dan Livingston is an attorney who has been a labor and progressive activist in three states – New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. A life-time member of the United Auto Workers Union, Dan is the product of the marriage of a Union President, and a Social Worker, who boasts of being on picket lines before he could walk. Dan worked for two years as a Union organizer before entering Yale Law School in 1979. He graduated in 1982, and has since been admitted to the Connecticut and Federal district court bars, as well as the to the bar of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court. Dan has been a member of the Firm for 35 years and has been a partner since 1984. He has extensive experience in labor and employment law including arbitrations, and litigation before the State Labor Relations Board, the National Labor Relations Board, the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights & Opportunities, the Connecticut Superior Court, the U.S. District Court, the Connecticut Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. He has represented hundreds of individuals in [email protected] discrimination, harassment, and wrongful termination cases against their 860-570-4625 employers. Dan also serves as chief negotiator in contract negotiations, and lead advocate in interest arbitrations, including the successful effort of State Employee Unions to secure health and pension benefits for domestic partners of the state's gay and lesbian employees when Connecticut law refused to allow same-sex marriage. Dan has been the Chief Negotiator for SEBAC, the State Employees Bargaining Agent Coalition since 1994. -

Spring 2014 a Publication of the University of Bridgeport

UB KNIGHTLINES SPRING 2014 A PUBLICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF BRIDGEPORT SPRING 2014 “ I feel strongly about UB being Why successful.” “ It would be so wonderful to give They a chance to more Give and more of these deserving kids. All institutions need support. ” Why UB’s donors answer the “ Being able to help call—and what they hope their gifts will mean. students is exactly “ UB will always have the kind of thing a very special place we wanted to be in the hearts of able to do.” those of us on the Alumni Board.” “ I’m proud I’m able to help out.” “ We wanted to create a way to ensure that there will be more doctors like her in the future.” “ There simply are a number of truly “ We’ll tell him talented people, why we did this. young and otherwise, It will help him in the region who see the person might not have any she was.” other chance to realize their dreams.” ALSO INSIDE Entrepreneurship 101 t Strongest Woman Ever! t The Little Lab That Could 1 UB KNIGHTLINES SPRING 2014 President’s Line There’s been quite a bit of talk about entrepreneurship lately. Pioneers from Steve Jobs to Mark Zuckerberg have changed the way we live and work. As the president of a university with a mission to prepare students to excel in the professional world, I’ve also witnessed how entrepreneurs are inspiring today’s students. But while entrepreneurship may be a hot topic on today’s college campuses, it’s certainly not a new concept. -

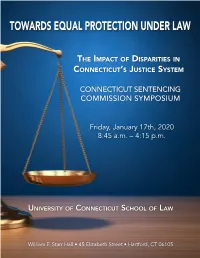

Symposium Program

TOWARDS EQUAL PROTECTION UNDER LAW THE IMPACT OF DISPARITIES IN CONNECTICUT’S JUSTICE SYSTEM CONNECTICUT SENTENCING COMMISSION SYMPOSIUM Friday, January 17th, 2020 8:45 a.m. – 4:15 p.m. UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT SCHOOL OF LAW William F. Starr Hall • 45 Elizabeth Street • Hartford, CT 06105 The Connecticut Sentencing Commission is an independent state criminal justice agency Robert J. Devlin, Jr. Jennifer L. Zito established to review, research, and make recommendations concerning Connecticut’s criminal justice system. Chair Attorney The Commission chairperson is Judge Robert J. Devlin, Jr. and Alex Tsarkov serves as the Executive Director. Appellate Court Judge Appointed by: President of the Connecticut Criminal Appointed by: Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Defense Lawyers Association The Commission consists of 23 voting members including judges, prosecutors, criminal defense counsel, the John Santa Gail Hardy commissioners of the departments of Correction, Public Safety, and Mental Health and Addiction Services, Vice Chairman State’s Attorney the victim advocate, the executive director of the Court Support Services Division of the Judicial Branch, Malta Justice Initiative Judicial District of Hartford a municipal police chief, the chairperson of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, the undersecretary of the Appointed by: Minority Leader of the Senate Appointed by: Chief State’s Attorney Criminal Justice Policy and Planning Division of the Office of Policy and Management, and members of the public appointed by the Governor and the leaders of the General Assembly. Marc Pelka Mark A. Palmer Undersecretary Chief of Police Office of Policy and Management Coventry Police Department Criminal Justice Policy and Planning Division Appointed by: President of the CT Police Chiefs Ex officio: Undersecretary for Criminal Association Justice Policy and Planning Division Vacant Patrick L. -

Dannel P. Malloy Biosketch

Chancellor University of Maine System Dannel P. Malloy A former prosecutor, lawyer, Mayor, and two-term Governor of Connecticut, Chancellor Dannel P. Malloy brings 22 years of public service leadership to the University of Maine System. Chancellor Malloy is leading the University of Maine System’s effort to unify Maine’s public universities in collaborative service to the students and people of Maine through the innovation of a first-in-the-nation state-wide unified accreditation from the New England Commission on Higher Education. With unified accreditation, the universities that make up the University of Maine System are now evaluated together based on how well they share state resources and academic programs in meeting accreditation standards for institutional quality and higher education effectiveness. Under Chancellor Malloy’s leadership the University of Maine In October 2020, the Harold Alfond Foundation announced a System is also in the midst of one of the nation’s safest $240 million gift to the University of Maine System, making returns to in-person class and work as the global COVID-19 investments in engineering, student success and retention, pandemic continues. Chancellor Malloy led the development graduate and professional programs, and Division 1 athletics of a safe reopening framework for all higher education and gender equity. This gift is the ninth largest ever to a institutions in Maine this spring, and has overseen the public institution of higher education and the biggest in New Together for Maine initiative that safely returned students to England’s history. Leaders of the Alfond Foundation signaled university campuses and classes this fall, managing a COVID a willingness to bet big on the future of Maine’s public testing positivity and prevalence rate so far of only one- universities because of the strategic direction and leadership tenth of one percent, with nearly half of all students having of the University of Maine System and its universities under at least one in-person class experience and the System’s Chancellor Malloy. -

Town Grieves Following Mass Murder at Sandy Hook Elementary School

SPECIAL EDITION Commemorating The Lives Lost Since 1877 - Best for Local In Sandy Hook On News and Advertising December 14, 2012 VOLUME CXXXIV Complimentary Issue NEWTOWN, CONNECTICUT, MONDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2012 Complimentary Issue SPECIAL EDITION On Friday, December 14, Sandy Hook Elementary School students and faculty put into practice safety precautions administrators never hoped to use: the evacuation of the building in an emergency. These students, accompanied by a pair of state troop- ers and another pair of school employees, were among the first to safely move to Sandy Hook Fire’s main station after Sandy Hook resident Adam Lanza had entered their school and shot 28 people inside the building, 26 of whom died. —Bee Photo, Hicks EDITORIAL INK DROPS 28 People Dead— Answering For Our Town The holiday season had already settled over Newtown like a snow globe, and the spirited center of Sandy Hook glittered with lights and bubbled with good cheer. Then on Friday morning a young man filled with anger and trouble, armed beyond reason, Town Grieves Following Mass Murder took deadly aim at Sandy Hook’s true heart — its elementary school. The violence wrought in the next several minutes left 26 dead, mostly 6- and 7-year-olds and several of the adults who tried to protect them. The scale and the horror of the crime still out- paces our capacity to understand it. We expect it always will. At Sandy Hook Elementary School The shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School shook and shattered the spell of Newtown’s picturesque holiday traditions, BY ANDREW GOROSKO The mass murder has drawn media attention the scene,” Lt Vance said. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

Mailed free to requesting homes in Thompson Vol. VII, No. 39 Complimentary to homes by request (860) 928-1818/e-mail: [email protected] FRIDAY, JUNE 22, 2012 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE “You can’t help getting older, but you don’t have to get old.” George Burns INSIDE A8— OPINION A12 — SPORTS B1 — HOT SPOT B5 — CALENDAR Under sunny skies, graduates marched to their seats. Kerensa Konesni photos B3— OBITS Two friends hold hands on their way to commencement. B3 — RELIGION LOCAL Summer Reading on the right track Page A2 LEARNING One of many emotional hugs last Thursday. MOVING ON THOMPSON — The 102nd Tourtellotte Memorial High School gradua- tion ceremony was held Thursday, June 14. For more photos, turn to page A6! For photos from Tuesday’s com- Two graduates pose with their diplomas. Quinebaug Middle College graduates 37 County closer to ‘Bike & Build’ team makes at ceremony Page A3 SPORTS ‘HEARTsafe’ first stop in region status STUDENTS BIKE BY KERENSA KONESNI VILLAGER STAFF WRITER CROSS-COUNTRY Windham County is on its way to becoming the first in the state to FOR AFFORDABLE have all of its municipalities desig- nated as “HEARTSafe” communi- HOUSING ties, under the Connecticut Department of Health’s BY KERENSA KONESNI HEARTSafe program. VILLAGER STAFF WRITER “We’re talk- POMFRET — Thirty young adults ing 50 more slept in the pews of the First people, and Congregational Church of Pomfret, the entire Saturday June 16. Rocco goes from last to county would “By the end of the day,we’re so tired first in exciting Sunoco be certified,” we’d sleep on concrete,” laughed Dan said Killingly Halpert. -

CRCOG Weekly Legislative Report 2019 Legislative Session May 30

CRCOG Weekly Legislative Report 2019 Legislative Session May 30, 2019 Weekly Legislative Feature Issues: There is just one more week in the regular legislative session and the Connecticut General Assembly has been holding daily sessions as they continue working on legislation. While these sessions have been convened, neither the House nor the Senate have been very productive. As previously reported, the only piece of major legislation that has achieved final passage through both chambers was HB No. 5004: AN ACT CONCERNING MINIMUM FAIR WAGE, which was signed by Governor Lamont on Tuesday, May 428th. There still remains a number of major issues, including paid family and medical leave, tolls, and the budget that have yet to be addressed by both chambers. Speaker of the House Joe Aresimowicz acknowledged during a press conference on May 30th that legalization of recreational marijuana will not be acted on during the regular legislative session. Governor Lamont has changed his position on when he would like to have the tolls issue addressed. Previously, he had suggested that electronic tolling legislation should be reserved for a special session but has since stated that he would prefer that it be completed by the end of the regular legislative session. For further details, you can access this article here: In Another Shift, Lamont Wants Regular Session Vote on Tolls. Breaking News: Governor Lamont joined by the democratic legislative leaders, Senate President Pro Tempore Martin Looney and Speaker of the House Joe Aresimowicz held a press conference today to announce that they have reached an agreement on a budget. -

Virtual Commencement May 8, 2021 University of Maine at Presque Isle

Virtual Commencement May 8, 2021 University of Maine at Presque Isle One Hundred Twelfth Commencement Saturday, May 8, 2021 10:30 am www.umpi.edu/virtual-graduation University of Maine at PRESQUE ISLE North of Ordinary Where Will Your Wings Take You? In honor of your graduation from the University of Maine at Presque Isle, all graduates will be receiving a snowy owl lapel pin in the mail. Depicting a snowy owl with its wings outstretched, consider this pin a symbol of the amazing things you will accomplish in the world when you leave here. And we’ve provided a way to ensure you can tell us about those accomplishments and adventures. Just visit yourwings.umpi.edu to submit a photo of yourself wearing this pin and share your story. While there, you can see what other alums have posted about where their wings have taken them, whether it’s a new job, a difference they’re making in their communities, or exploring a new spot in the world. Remember your wings. Soar to great heights. And don’t forget to ‘write home’ about it! program ALMA MATER Rise Up Presque Isle by Ellis Paul Performance by Anatole Wieck, violin Professor of Music, University of Maine Orono, Maine Musical Arrangement by Benjamin Walker SOLOIST Bethany E. Lord National Anthem WELCOME Raymond J. Rice President GREETING Dannel Malloy Chancellor, University of Maine System GREETING James Erwin Chair, Board of Trustees, University of Maine System GREETING Steve Richard Board of Visitors GREETING Stacey Emery Chair, Faculty Assembly program INTRODUCTION OF SPEAKER Raymond J.