Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Northwest Friend, September 1959

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Northwest Friend (Quakers) 9-1959 Northwest Friend, September 1959 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "Northwest Friend, September 1959" (1959). Northwest Friend. 186. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend/186 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwest Friend by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Left to right: Dean Gregory, General Superintendent of Oregon Yearly Meeting; Keith Sarver, General Superintendent of California Yearly Meeting and recent guest speaker for our yearly meeting sessions; Dorwin E. Smith, presiding clerk. //i ^ .The^ Irish Quakers used a verb in their letter of greeting to the e«E^ngelical Friends Conference that could be useful in Oregon Yearly COUNT down... ^ Meeting: "May your meetings be presenced by the Spirit of the Lord." a travelogue of Gerald Dillon's trip yWhen this happens it is an impressive and fearful thing. The first announcement of God's redemptive intention toward mankind was made "We're off . it's just 11:40 p.m.," ob to a man and a woman hiding in mortal fear from the presence of the Lord. The Law of God was given to a man trembling in terror amid fire served Everett Heacock, as together we started a journey around the world. -

A Brief Survey of Missions

2 A Brief Survey of Missions A BRIEF SURVEY OF MISSIONS Examining the Founding, Extension, and Continuing Work of Telling the Good News, Nurturing Converts, and Planting Churches Rev. Morris McDonald, D.D. Field Representative of the Presbyterian Missionary Union an agency of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA P O Box 160070 Nashville, TN, 37216 Email: [email protected] Ph: 615-228-4465 Far Eastern Bible College Press Singapore, 1999 3 A Brief Survey of Missions © 1999 by Morris McDonald Photos and certain quotations from 18th and 19th century missionaries taken from JERUSALEM TO IRIAN JAYA by Ruth Tucker, copyright 1983, the Zondervan Corporation. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, MI Published by Far Eastern Bible College Press 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063 Republic of Singapore ISBN: 981-04-1458-7 Cover Design by Charles Seet. 4 A Brief Survey of Missions Preface This brief yet comprehensive survey of Missions, from the day sin came into the world to its whirling now head on into the Third Millennium is a text book prepared specially by Dr Morris McDonald for Far Eastern Bible College. It is used for instruction of her students at the annual Vacation Bible College, 1999. Dr Morris McDonald, being the Director of the Presbyterian Missionary Union of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA, is well qualified to write this book. It serves also as a ready handbook to pastors, teachers and missionaries, and all who have an interest in missions. May the reading of this book by the general Christian public stir up both old and young, man and woman, to play some part in hastening the preaching of the Gospel to the ends of the earth before the return of our Saviour (Matthew 24:14) Even so, come Lord Jesus Timothy Tow O Zion, Haste O Zion, haste, thy mission high fulfilling, to tell to all the world that God is Light; that He who made all nations is not willing one soul should perish, lost in shades of night. -

The Consummation: the Crucial Ministries Involved

The Consummation: The Crucial Ministries Involved Reaching the peoples of the 10/40 Window has been greatly advanced by a variety of support and media ministries. Immense efforts are being poured into these ministries, all of which have the potential of completely covering the world’s population and peoples. In this article the author briefly describes the impact of the major mega-ministries working to help reach the unreached peoples of the world. by Patrick Johnstone an we really see church planting believers in a small tribe of 1,000 can Translating the C initiatives launched for all peo- be significant, but one church among Scriptures ples within our present generation? the 6 million Tibetans or a few It is almost impossible to conceive Some might question that. In answer I churches among the 200 million Ben- of a strong church within a people report on what transpired in GCOWE- galis is less than a drop in the bucket. that has no word of the Bible trans- 97 in South Korea. Our aim should be at minimum a lated into their own language. The Luis Bush, the Director of the church for every people, but this is lack of the Scriptures for the Berber AD2000 Mvt., made a great effort dur- only a beginning. This is where the languages of North Africa was a signif- ing GCOWE-97to encourage mission Discipline a Whole Nation vision of icant factor in the surprising disap- agencies represented and the various Jim Montgomery is so valid. We need pearance of the once-large North Afri- national delegations to commit them- to ensure that there is a vital, wor- can Church between the coming of selves to reaching each of the remain- shiping group of believers within easy Islam in 698 and the twelfth century. -

Missions in the Third Millennium by Stan Guthrie

Missions in the Third Millennium by Stan Guthrie Note: The following is from the book by the same title as this article. The author, Stan Guthrie, is now with Christianity Today magazine and is the former editor of Evangelical Missionary Quarterly and World Pulse. In his book, Mr. Guthrie highlights characteristics and challenges of modern day missions. The vitality that marks the most dynamically missionary churches is today most readily observed in the great continents of Africa, Asia, and South America. That this should be so is not surprising, since Christianity has seldom, if ever, remained healthy and vigorous within rich, dominant societies. The North American component of the global Christian missionary force is, accordingly, a steadily diminishing proportion of the whole. In 1900 there were an estimated 16,000 missionaries, most of these from Europe, Great Britain, and North America. Today, the total number is some 420,000, with a mere 12-15 percent of these hailing from Western lands. In 1900, the total number of distinct and organizationally separate denominational bodies in the world stood at 1,880. Today the estimate stands at more than 30,000, a majority of these outside of North America and Europe. Some 4,000 people groups in the world have no viable Christian witness, according to missions statistician David Barrett. There are an estimated 1.556 billion people in the world who have never heard the Gospel. The number of people born in the non-Christian world grows by 129,000 a day, or 47 million a year. Clearly, if fulfilling the Great Commission depends on seeing that everyone hears, it is nowhere near completion. -

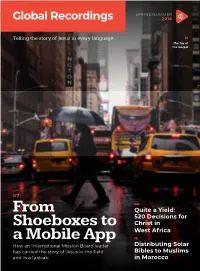

From Shoeboxes to a Mobile App: Carrying the Story of Jesus

J SPRING/SUMMER 2018 Telling the story of Jesus in every language 15 The Joy of the Gospel 07 04 Quite a Yield: From 520 Decisions for Christ in Shoeboxes to West Africa a Mobile App 15 How an International Mission Board leader Distributing Solar has carried the story of Jesus in the field Bibles to Muslims and in a taxicab in Morocco My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me. JOHN 10:27 06 SCRIPT SPOTLIGHT A PUBLICATION OF GLOBAL RECORDINGS NETWORK USA 04 PARTNER PROFILE Treating Trauma Flagstaff Christian with Tigers Executive Director Fellowship Dale Rickards GRN and its partners use targeted scripts, Telling the story of Christ’s love in recordings, and stuffed animals to help Storytellers and Contributors Gambia and Guinea-Bisau children heal Augustus McJohnson | GRN Gambia Linda Martin | Flagstaff Christian Fellowship Christine Platt | GRN Australia Dalene Joubert | GRN South Africa Jim Haney | International Mission Board Elizabeth Chan | GRN USA Elise Cooper | GRN International Dale Rickards | GRN USA GRN USA and International Teams 07 FEATURE STORY Managing Editor, Design & Production Cahoots Communications, Inc., CahootsInc.com From Shoeboxes to Photography Contributions GRN, MegaVoice, Courtesy of IMB a Mobile App and Jim Haney How an International Mission Board leader has carried the story of Jesus in the field and in a taxicab Thank You Through the stories and recordings of our missionaries, churches, ministry partners, and friends, Global Recordings USA is able to continue: Our Vision That people might hear and understand God's Word in their heart language, especially those 12 A SOUND RESOURCE who are oral communicators and those who do 11 TELLING THE STORY OF JESUS not have Scriptures in a form they can access. -

History of Missions

History of Missions In Suriname, they say: “Learn from others and don’t make them learn from you.” They mean that we should study history to avoid the mistakes of the past. Some have said: Those who ignore history will repeat the mistakes of the past. We have a glorious history of God’s dealing with mankind. Let’s learn from it. I will mention that the first few pages outline briefly the missions emphasis of the Bible. This is covered in much more detail in the section on Theology of Missions. The reader who has already studied that section might want to just skim or even skip over the first few pages to the sections beginning with the church fathers. When we take a dispensational view of history, we can break the history in the Bible into seven segments. The first three are included in a time that God was dealing with all mankind. The first, of course, was the time of innocence, from the creation of Adam and Eve to their fall into sin. The second was the time of conscience, when man, now knowing good and evil, had a conscience to show him what he should do. But with a sin nature, man inevitably chose what was evil, and not good. Eventually God judged mankind, and only eight humans survived the flood. Third, we reach the time of human government, extending from the flood to the tower of Babel. Mankind refused to fill the earth, but rebelled to set up a human kingdom. God judged them and dispersed them by changing their languages. -

Adopt-A-People. It Is Difficult to Sustain A

AIDS and Mission Adopt-a-People. It is difficult to sustain a mis- birth has declined—to 37 years in Uganda, for sion focus on the billions of people in the world example, the lowest global life expectancy. By or even on the multitudes of languages and cul- 2010 a decline of 25 years in life expectancy is tures in a given country. Adopt-a-people is a mis- predicted for a number of African and Asian sion mobilization strategy that helps Christians countries. In Zimbabwe it could reduce life ex- get connected with a specific group of people pectancy from 70 to 40 years in the next 15 who are in spiritual need. It focuses on the goal years. Sub-saharan Africa, with less than 10 per- of discipling a particular people group (see PEO- cent of the world’s population, has 70 percent of PLES, PEOPLE GROUPS), and sees the sending of the world’s population infected with HIV. missionaries as one of the important means to Asia, the world’s most populous region, is fulfill that goal. poised as the next epicenter of the epidemic. Ini- Adopt-a-people was conceptualized to help tially spread in the region primarily by drug in- congregations focus on a specific aspect of the jection and men having sex with men, heterosex- GREAT COMMISSION. It facilitates the visualization ual transmission is now the primary cause of of the real needs of other people groups, enables infection. It is expected that child mortality in the realization of tangible accomplishments, de- Thailand, where the sex-tourism industry has fu- velops and sustains involvement, and encourages eled the epidemic, will triple in the next 15 years more meaningful and focused prayer. -

Quotes from MISSIONS in the THIRD MILLENNIUM

Missions in the Third Millennium (21 Key TRENDS for the 21st Century) by Stan Guthrie, Paternoster Publishing, Waynesboro, GA, 2000 (77 Quotes selected by Doug Nichols) 1. Missions Becoming Stronger In Less Prosperous Countries. The Christian “center of gravity” is no longer the West whose Christian confidence has been steadily leavened by the subliminal agnosticism that almost always accompanies prosperity (Rev. 3:14-20). The vitality that marks the most dynamically missionary churches is today most readily observed in the great continents of Africa, Asia, and South America. That this should be so is not surprising, since Christianity has seldom, if ever, remained healthy and vigorous within rich, dominant societies. The North American component of the global Christian missionary force is, accordingly, a steadily diminishing proportion of the whole. In 1900 there were an estimated 16,000 missionaries, most of these from Europe, Great Britain, and North America. Today, if we use David Barrett‟s more expansive definition for foreign missionaries (not limited to those who earn their living as missionaries), the total number is some 420,000, with a mere 12-15 percent of these hailing from Western lands. [Page xii] 2. Growing Numbers Outside of North America and Europe. In 1900, the total number of distinct and organizationally separate denominational bodies in the world stood at 1,880. Today the estimate stands at more than 30,000, a majority of these outside of North America and Europe. [Page xiii] 3. The Great Commission. Mission, the outward focus of people who want to share the good news of Jesus Christ with peoples who don‟t necessarily want to hear about him, has always been God‟s idea first. -

The Tailenders a Film by Adele Horne

n o s a e P.O.V. 19S Discussion Guide The Tailenders A Film by Adele Horne www.pbs.org/pov P.O.V. n o The Tailenders s Discussion Guide | a 19e S Letter from the Filmmaker LOS ANGELES, MAY 2006 Dear Colleague, I became aware of the recordings and unusual audio players that Global Recordings Network produces because I grew up in an evangelical Christian family. One day in the mid-1970s we received a package in the mail from a missionary friend. It contained a record player made out of a piece of cardboard folded into a triangle. A small phonograph needle protruded from one edge of the cardboard. The 78-rpm record that came with it had a hole drilled near the center so that you could stick a pencil in and turn it by hand. The record played the story of Noah on one side and a message about “Christ Our Savior” on the other. The simplicity of this device, which worked without speakers or electric power, made a lasting impression on me. Twenty years later I decided to learn more about the organization that made it. I became completely fascinated by the story of how Global Recordings Network makes and distributes recordings of Bible stories in indigenous languages. A missionary named Joy Ridderhof founded the organization in 1939 in Los Angeles, a few miles away from famous radio evangelists Aimee Semple MacPherson and Charles Fuller. Like them, Ridderhof believed in the power of media and entertainment to spread the gospel message. She remembered how crowds had gathered around gramophones in the Honduran villages where she had worked as a missionary, and decided that rather than compete with this burgeoning medium, she would use it to preach. -

Reaching the Non-Literate Peoples of the World

Editorial: Reaching the Non-Literate Peoples of the World hese are very exciting days as we multitudes of non-readers are usually the a proper understanding of salvation. All T see our Lord building His least reached with the Gospel. It’s the non-literate unreached peoples of Church and drawing to Himself people becoming increasingly obvious that the the world must be reached with the mes- from every people, tribe, tongue and only way they will be reached is sage of Christ! nation. Yet despite great progress, there through some form of Gospel audio- This special edition of the Journal are still formidable barriers that need communication strategy. Like the focuses on that awesome challenge. to be overcome. Among these are the lit- Blackfoot Indians of North America, who What will it take for the Gospel to be eracy (illiteracy) and language bar- prefer audio-Scriptures, and have lit- available to all the peoples of the riers. Not only do we need to be aware of tle or no interest in learning to read, earth—including the thousands of non- these barriers, but also to take note of including their own language. In reading peoples? Certainly it will the tools that God has put into our hands some cultures this changes, but usually take prayer and intercession, coupled to penetrate them. only after they become Christian. with a new perspective of the task at Thanks to the tireless work done by However, even at that, examples abound hand and new ways to communicate the Bible translators, nearly 2,000 lan- where Scripture translations have Word. -

African Initiated Church Movement. Originally

African Mission Boards and Societies African Initiated Church Movement. Originally World Council of Churches, as well as a member an unanticipated product of the modern mission- council of the All Africa Conference of Churches. ary movement in Africa, the African Independent Bibliocentric and christocentric throughout Churches (AICs) today number 55 million church their history, these churches are now producing members in some 10,000 distinct denominations radically new Christian theology and practice. A present in virtually all of Africa’s 60 countries. notable example is earthkeeping, a blend of theo- This title is the most frequent descriptive term in logical environmentalism or caring for God’s cre- the current literature of some 4,000 books and ar- ation, especially in relation to land, trees, plants, ticles describing it. However, because Western natural resources, and in fact the whole of God’s denominations and Western-mission related creation. churches in Africa regard themselves also as “in- DAVID B. BARRETT dependent,” African AIC members have since 1970 promulgated the terms African Instituted African Mission Boards and Societies. A study Churches, or African Indigenous Churches, or of the general landscape of African mission locally founded churches. Some Western scholars boards and societies reveals that the majority of still use the older terms African Separatist the work to date has taken place in the Anglo- Churches or NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS. phone countries, particularly West Africa (Nige- These movements first began with a secession ria and Ghana). In Eastern and Central Africa, from Methodist missions in Sierre Leone in largely Christian churches seem to assume either 1817.