Roger Federer V. Novak Djokovic: Joy V. Rage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Djokovic Faces British Teen at Wimbledon As Halep Withdraws Defending Champion Simona Halep Withdraws from Wimbledon with Calf Injury

SATURDAY, JUNE 26, 2021 11 ‘Dynamic’ Belgium staying true to attacking style for Portugal Djokovic faces British teen at Wimbledon as Halep withdraws Defending champion Simona Halep withdraws from Wimbledon with calf injury Novak Djokovic to play• British teenager BETTER Jack Draper KNOW AFP | London Belgium’s Spanish coach Roberto Martinez looks on during a training session AFP | London efending champion Si- Halep’s withdrawal mona Halep pulled out follows that of four- oach Roberto Martinez Dof Wimbledon with a time Grand Slam Csaid Belgium won’t alter calf injury as Novak Djokovic champion Naomi their approach for Sunday’s We cannot change learned yesterday he will face Euro 2020 last-16 tie against who we are. We’re a Britain’s Jack Draper at the start Osaka, who pulled out holders Portugal despite the dynamic team built of his quest for a 20th Grand of the French Open threat of the tournament’s to attack and to get Slam title. after citing struggles leading scorer Cristiano Ron- at the opposing goal Romanian Halep, who beat with depression and aldo. as soon as possible, Serena Williams in the final in anxiety Belgium, the world’s top- but we’ll have to be 2019, tore her left calf muscle in ranked side, face a difficult Rome last month and was forced champion Andy Murray are in draw after taking maximum patient to miss the French Open. the draw but there are fitness ROBERTO MARTINEZ 2019 Wimbledon Men’s singles champion Serbia’s Novak Djokovic (L) and points from their three Group She travelled to London earli- Wimbledon Women’s singles champion Romania’s Simona Halep (R) poses for a doubts over both players. -

Media Guide Template

MOST CHAMPIONSHIP TITLES T O Following are the records for championships achieved in all of the five major events constituting U R I N the U.S. championships since 1881. (Active players are in bold.) N F A O M E MOST TOTAL TITLES, ALL EVENTS N T MEN Name No. Years (first to last title) 1. Bill Tilden 16 1913-29 F G A 2. Richard Sears 13 1881-87 R C O I L T3. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 U I T N T3. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 Y D & T3. Neale Fraser 8 1957-60 S T3. Billy Talbert 8 1942-48 T3. George M. Lott Jr. 8 1928-34 T8. Jack Kramer 7 1940-47 T8. Vincent Richards 7 1918-26 T8. Bill Larned 7 1901-11 A E C V T T8. Holcombe Ward 7 1899-1906 E I N V T I T S I OPEN ERA E & T1. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 S T1. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 T3. Todd Woodbridge 6 1990-2003 T3. Jimmy Connors 6 1974-83 T5. Roger Federer 5 2004-08 T5. Max Mirnyi 5 1998-2013 H I T5. Pete Sampras 5 1990-2002 S T T5. Marty Riessen 5 1969-80 O R Y C H A P M A P S I T O N S R S E T C A O T I R S D T I S C S & R P E L C A O Y R E D R Bill Tilden John McEnroe S * All Open Era records include only titles won in 1968 and beyond 169 WOMEN Name No. -

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest for Perfection

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER New Chapter Press Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic Originally published in Germany under the title “Das Tennis-Genie” by Pendo Verlag. © Pendo Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich and Zurich, 2006 Published across the world in English by New Chapter Press, www.newchapterpressonline.com ISBN 094-2257-391 978-094-2257-397 Printed in the United States of America Contents From The Author . v Prologue: Encounter with a 15-year-old...................ix Introduction: No One Expected Him....................xiv PART I From Kempton Park to Basel . .3 A Boy Discovers Tennis . .8 Homesickness in Ecublens ............................14 The Best of All Juniors . .21 A Newcomer Climbs to the Top ........................30 New Coach, New Ways . 35 Olympic Experiences . 40 No Pain, No Gain . 44 Uproar at the Davis Cup . .49 The Man Who Beat Sampras . 53 The Taxi Driver of Biel . 57 Visit to the Top Ten . .60 Drama in South Africa...............................65 Red Dawn in China .................................70 The Grand Slam Block ...............................74 A Magic Sunday ....................................79 A Cow for the Victor . 86 Reaching for the Stars . .91 Duels in Texas . .95 An Abrupt End ....................................100 The Glittering Crowning . 104 No. 1 . .109 Samson’s Return . 116 New York, New York . .122 Setting Records Around the World.....................125 The Other Australian ...............................130 A True Champion..................................137 Fresh Tracks on Clay . .142 Three Men at the Champions Dinner . 146 An Evening in Flushing Meadows . .150 The Savior of Shanghai..............................155 Chasing Ghosts . .160 A Rivalry Is Born . -

Boris Becker Kruger Cowne Tennis Legend, Commentator, Entrepreneur & Businessman

BORIS BECKER KRUGER COWNE TENNIS LEGEND, COMMENTATOR, ENTREPRENEUR & BUSINESSMAN In 1985, at the age of 17, Boris Becker became, and remains, the youngest ever winner of The Championships, Wimbledon. Over the course of his career, he won a total of 49 titles, and his success helped to make tennis a national sport in Germany. Since his retirement from professional tennis, he is a tennis commentator for Sky and the BBC, and writes a sports column for The Times. His is also the founder of Boris Becker GmbH and provides testimonials for selected brands, including Mercedes-Benz, IWC, Rodenstock and Pokerstars. As well as this, he is Vice Chairman and an academy member of the Laureus Sports for Good Foundation, is an ambassador for the German AIDs Foundation and a Member of the Board of the Elton John AIDs Foundation. His illustrious career spanned two decades, and he continues to entertain and inspire audiences with details of his experiences as a top international tennis player, and the lessons he learned when dealing with the insatiable media. An engaging, gregarious personality, he can present in German or English, and is always inspirational. More recently, Boris became Novak Djokovic’s head coach in an attempt to futher advance the Serbian Star’s tennis career. A highly entertaining Awards Host, full of wit and charm. His reputation as a tennis star is preceeded only by his ability to draw in an audience...” “ Procurement Leaders POPULAR TOPICS AVAILABLE FOR ENTREPRENEURIALISM PUBLIC SPEAKING - AWARDS HOSTING - PUBLIC TEAMWORK APPEARANCES - ENDORSEMENTS - PUBLISHING - ANECDOTES OF HIS LIFE MASTER CLASSES & DEMOS - TV & FILM - COACHING & MENTORING © Kruger Cowne 2015 | www.krugercowne.com | +44 20 7352 2277 | 15 Lots Road, Chelsea Wharf, London SW10 0QJ •t info [email protected]@LondonSpeakerBureauAsia.my t • +603 +603 2301 2301 0988 0988 t •www.londonspeakerbureau.com LondonSpeakerBureauAsia.com t • TheThe world’sworld’s leadingleading speakerspeaker andand advisory advisory network network . -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d. -

Tennis MEDIA Guide 2012 2012 TULSA Tennis Media Guide

The Official Tulsa Golden Hurricane TENNIS MEDIA Guide 2012 www.tulsahurricane.com 2012 TULSA TENNIS Media Guide Table of Contents TULSA QUICK FACTS Introduction 1 Individual/Team Honors ................................. 20-21 Location: Tulsa, Oklahoma Year-By-Year Conference Results .......................22 Founded: 1894 Table of Contents .................................................1 Hall of Fame .........................................................22 Enrollment: 4,187 Tulsa Quick Facts .................................................1 Region Champions ...............................................22 Nickname: Golden Hurricane The University of Tulsa ........................................2 All-Americans................................................. 23-24 Colors: Old Gold, Royal Blue and Crimson The City of Tulsa ..................................................3 National Champions ............................................24 Conference: Conference USA Michael D. Case Tennis Center ...........................4 All-Time Letterwinners ........................................25 Affiliation: NCAA Division I President ..............................................................5 President: Dr. Steadman Upham Director of Athletics .............................................5 Women’s Team 26 Faculty Representative: Chris Anderson Director of Athletics: Ross Parmley Staff 6 Team Photo/Roster ..............................................26 Associate Athletic Director/SWA: Crista Troester Player Profiles ............................................... -

Federer Reaches Semis at ATP Finals

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2013 SPORTS Ruthless Aussies thrash Italy 50-20 TURIN: Wing Nick Cummins scored two nisingly close to victory over the and worked hard through the game to Australia a line-out on Italy’s 22-metre Italy were given brief hope of a fight- of seven Australian tries as the Wallabies Wallabies in a 19-22 reverse last year. score those points. So there was consis- line and led to the Wallabies’ fourth try back when replacement Lorenzo made up for defeat to England with a “After the first half, or at least the first tency there, and we had to work hard in on 50 minutes. Cittadini bundled the ball over shortly commanding 50-20 victory over hapless 30 minutes, I saw some quality play defence at different times.” Italy’s posi- Adam Ashley-Cooper played a piv- after to add five points, but Di Italy at the Olympic Stadium yesterday. from Italy. But we gave away errors tive start was soon brought to heel. otal role, holding off several players and Bernardo’s disappointing afternoon Italy had been looking to capitalise cheaply and at the end of the day our Captain Ben Mowen touched down causing confusion metres from the try- with the boot continued when he on Australia’s morale-sapping 20-13 defence certainly wasn’t up to the job.” for Australia on 15 minutes, with Quade line before offloading to Cummins who missed the conversion. reverse at Twickenham last week to Australia’s dominance was never under Cooper making up for an earlier penalty sneaked aroud him to run in behind the There was no stopping Australia, and score a first, historic win over Australia threat but their defence was given a miss with the conversion before adding posts for his second. -

Tennis Edition

Commemorative Books Coverage List Wimbledon Tennis 2017 Date of Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) Paper 5 July 1913 Page 11 Anthony Wilding (N.Z) defeats Maurice McLoughlin to win his fourth singles title Dorothea Lambert Chambers wins her seventh singles title. 6 July 1914 Page 4 Norman Brookes beats Anthony Wilding in the men’s final 6 July 1919 Back Suzanne Lenglen (Fr) beats Dorothea Lambert Chambers in the ladies’ final Bill Tilden (US) wins the men’s singles. Suzanne Lenglen wins Triple Crown 4 July 1920 Back 4 July 1925 Page 2 Suzanne Lenglen wins the ladies singles for the sixth time 3 July 1926 Page 8 Jean Borotra (Fr) defeats Howard Kinsey to win his second singles title Henri Cochet (Fr) and Helen Wills (USA) win the singles titles for the first time 3 July 1927 Page 3 7 July 1928 Page 26 Rene Lacoste (Fr) defeats Henri Cochet to win his second singles title 7 July 1929 Pages 3 and back Henri Cochet (Fr) defeats Jean Borotra to win the men’s singles title for the second time Bill Tilden defeats Wilmer Allison to win the men’s title for a third time 6 July 1930 Back 7 July 1934 Pages 1 and 26 Fred Perry (GB) defeats Jack Crawford in the men’s singles final 9 July 1934 Page 27 Dorothy Round (GB) defeats Helen Jacobs in the ladies’ singles final 6 July 1935 Page 26 Fred Perry retains his singles title after defeating Gottfried von Cramm 4 Jul 1936 Pages 14 and 26 Fred Perry defeats Gottfried von Cramm to win his third successive singles title Don Budge (USA) wins Triple Crown, and Dorothy Round wins her second title -

Legalnotice Djokovic Raises His Game to a New Level

8C z MONDAY, JANUARY 28, 2019 z THE ENQUIRER OHIO Tennis Djokovic raises his game to a new level Howard Fendrich and stretched and occasionally even Australian dominance ASSOCIATED PRESS did the splits, contorting his body to get wherever and whenever he need- Novak Djokovic, Roger Federer and MELBOURNE, Australia – Novak ed. Rafael Nadal have won 14 of the past Djokovic was so good, so relentless, so Djokovic grabbed 13 of the first 14 16 Australian Opens: flawless, that Rafael Nadal never stood points, including all four that lasted 10 2019 — Novak Djokovic a chance. strokes or more. A trend was estab- Djokovic reduced one of the greats lished. 2018 — Roger Federer of the game to merely another out- Of most significance, Nadal was 2017 — Roger Federer classed opponent – just a guy, really – broken the very first time he served and one so out of sorts that Nadal even Sunday. That gave Djokovic one more 2016 — Novak Djokovic whiffed on one of his famous fore- Novak Djokovic dominated Rafael break of Nadal than the zero that the 2015 — Novak Djokovic hands entirely. Nadal 6-3, 6-2, 6-3 to win a record Spaniard’s five preceding opponents In a breathtakingly mistake-free seventh Australian Open title and a had managed. 2014 — Stan Wawrinka performance that yielded a remark- third consecutive Grand Slam Nadal could make no headway on 2013 — Novak Djokovic ably lopsided result, the No. 1-ranked championship. GETTY IMAGES this day. Djokovic won each of the ini- Djokovic overwhelmed Nadal 6-3, 6-2, tial 16 points he served and 25 of the 2012 — Novak Djokovic 6-3 on Sunday night to win a record first 26. -

August—September 2017

August—September 2017 President Des Shaw [email protected] January Morning Tea Notice Council AGM Hon Treasurer Paul Thomson [email protected] SEED ...Jade Lewis News from Ron Dutton Hon Sec. Angela Hart [email protected] Peter Doohan & Mervyn Rose Editor Cecilie McIntyre [email protected] Blast From the Past Fed Cup Link to IC Council website www.ictennis.net Wimbledon Snippets Drop Shots Our Annual Morning Tea Notice. Last week all members on email were sent details of how to reserve your FREE ticket and gate passes to the morning teas held on both Mondays of the International Tournaments in Auckland in early January. (Women to the ASB Classic Women’s week on Monday 1st January, and Men to the ASB Classic Men’s week on Monday 8th January.. We must stress that although there is no charge, and you can ask for a ground pass for a partner to come with you to both the morning teas, if they want to sit in the stand with you, you must pay for those tickets. The cut off date for requests is 29th September and forms, with or without extra ticket payments MUST be returned to Angela before then. Every year since we have been doing this there have been last minute requests….but no late applications will be accepted this year. In the past the return forms have gone to Tennis Auckland but now, although payment is still made out to Tennis Auckland they need to be sent to Angela. DON’T leave it till the last days. -

Novak Djokovic Press Conference

Rolex Monte-Carlo Masters Principality of Monaco Sunday, 11 April 2021 Novak Djokovic Press Conference at the moment. THE MODERATOR: Questions, please. Felix is a great guy. He's someone that has hard-working Q. You obviously haven't played since Australia, ethics, which is something that is very important for Toni. I which is not a typical schedule for you. Is there any wish them all the best. It's nice to see Toni on the tour. specific adjustment you feel you need to make, Obviously he's had his mark with Rafa for so many years. I whether mentally, physically, to feel prepared for the feel like he can only bring positives to Felix's game and clay season? mindset. NOVAK DJOKOVIC: Well, not in particularly. I have had Q. As you said, you live here. It's your everyday some periods in my career where I didn't play a tournament training camp, if I can say. How is it to see the club for maybe couple months, then came back. So, I mean, I almost as it is in your everyday life, different from the don't think there is anything special I have to do in terms of tournament usually? Will you feel different when you preparation in order for me to feel my best on the court. enter the court for your first match? I've been training quite a lot on clay. Actually ever since I NOVAK DJOKOVIC: Well, it's definitely going to be a pulled out from Miami, I was hitting on clay. -

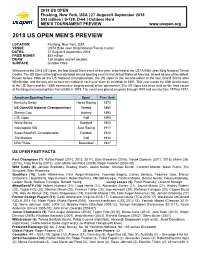

2018 Us Open Men's Preview

2018 US OPEN Flushing, New York, USA | 27 August-9 September 2018 $53 million | S-128, D-64 | Outdoor Hard MEN’S TOURNAMENT PREVIEW www.usopen.org 2018 US OPEN MEN’S PREVIEW LOCATION: Flushing, New York, USA VENUE: USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center DATES: 27 August-9 September 2018 PRIZE MONEY: $53 million DRAW: 128 singles and 64 doubles SURFACE: Outdoor Hard Welcome to the 2018 US Open, the last Grand Slam event of the year, to be held at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. The US Open is the highest-attended annual sporting event in the United States of America, as well as one of the oldest. Known before 1968 as the US National Championships, the US Open is the second-oldest of the four Grand Slams after Wimbledon, and the only one to have been played each year since its inception in 1881. This year marks the 50th Anniversary of the US Open and the 138th consecutive staging overall of the tournament. The US Open has been held on the hard courts of Flushing since moving from Forest Hills in 1978. The event was played on grass through 1974 and on clay from 1975 to 1977. American Sporting Event Sport First Held Kentucky Derby Horse Racing 1875 US Open/US National Championships Tennis 1881 Stanley Cup Hockey 1893 U.S. Open Golf 1895 World Series Baseball 1903 Indianapolis 500 Auto Racing 1911 Super Bowl/NFL Championship Football 1920 The Masters Golf 1934 NBA Finals Basketball 1947 US OPEN FAST FACTS Past Champions (7): Rafael Nadal (2010, 2013, 2017), Stan Wawrinka (2016), Novak Djokovic (2011, 2015), Marin Cilic