The Peculiar History of Hong Kong 'Heterotopias'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

I Am Sorry. Would Members Please Deal with One Piece of Business. It Is Now Eight O’Clock and Under Standing Order 8(2) This Council Should Now Adjourn

4920 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 29 June 1994 8.00 pm PRESIDENT: I am sorry. Would Members please deal with one piece of business. It is now eight o’clock and under Standing Order 8(2) this Council should now adjourn. ATTORNEY GENERAL: Mr President, with your consent, I move that Standing Order 8(2) should be suspended so as to allow the Council’s business this evening to be concluded. Question proposed, put and agreed to. Council went into Committee. CHAIRMAN: Council is now in Committee and is suspended until 15 minutes to nine o’clock. 8.56 pm CHAIRMAN: Committee will now resume. MR MARTIN LEE (in Cantonese): Mr Chairman, thank you for adjourning the debate on my motion so that Members could have a supper break. I hope I can secure a greater chance of success if they listen to my speech after dining. Mr Chairman, on behalf of the United Democrats of Hong Kong (UDHK), I move the amendments to clause 22 except item 12 of schedule 2. The amendments have already been set out under my name in the paper circulated to Members. Mr Chairman, before I make my speech, I would like to raise a point concerning Mr Jimmy McGREGOR because he was quite upset when he heard my previous speech. He hoped that I could clarify one point. In fact, I did not mean that all the people in the commercial sector had not supported democracy. If all the voters in the commercial sector had not supported democracy, Mr Jimmy McGREGOR would not have been returned in the 1988 and 1991 elections. -

Distributor Application Main Page

Distributor Application and Agreement Complete application or apply online at www.SeneGence.com PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY USING A DARK PEN Sponsor’s Name Sponsor’s ID Number PLEASE COMPLETE THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION: Shipping Address (NO P.O. Boxes) Full Legal Name of Applicant (Last, First, Middle Initial) Applicant Hong Kong Identity Card Number (HKID) Birthday District D D M M Daytime Telephone Number Evening Telephone Number Fax Number Mobile Phone Number Email Address My signature below indicates that I have read and accepted all the terms and conditions regarding privileges and obligations as set forth in the Terms of Application and Agreement, on the back of this agreement and that I have read and agree to be bound by the Policies and Procedures Guide. All signatures to this application must be affixed personally. Applicant must be of legal age and a resident of Hong Kong. A PARTICIPANT HAS THE RIGHT TO CANCEL AT ANY TIME, REGARDLESS OF REASON. CANCELLATION MUST BE SUBMITTED IN WRITING TO THE COMPANY AT ITS PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ADDRESS: Unit 613 6/F Mira Place Tower A, 132 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong. email: [email protected] Tel: +852 3892 823 X Signature of Applicant Date DD / MM / YY For efficient handling of your application, please sign and return both the front and back of this document. Applications without both signatures will not be accepted by SeneGence. SeneGence reserves the right to refuse the acceptance of any Distributor Application or to rescind such acceptance within thirty (30) days, for any reason. I object to Senegence using my personal data in direct marketing as referred to in the section entitled 'Use of Personal Data in Direct Marketing* ' of the notice. -

A Study on the Fire Safety Management of Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong 香港公共房屋消防安全管理制度之探討

Copyright Warning Use of this thesis/dissertation/project is for the purpose of private study or scholarly research only. Users must comply with the Copyright Ordinance. Anyone who consults this thesis/dissertation/project is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no part of it may be reproduced without the author’s prior written consent. CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG 香港城市大學 A Study on the Fire Safety Management of Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong 香港公共房屋消防安全管理制度之探討 Submitted to Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering 土木及建築工程系 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Engineering Doctorate 工程學博士學位 by Yeung Cho Hung 楊楚鴻 September 2012 二零一二年九月 i Abstract of dissertation entitled: A Study on the Fire Safety Management of Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong submitted by YEUNG CHO HUNG for the degree of Engineering Doctorate in Civil and Architectural Engineering at The City University of Hong Kong in September, 2012. ABSTRACT At the end of the Pacific War, there were a large number of refugees flowing into Hong Kong from the Mainland China. Many of them lived in illegal squatter areas. In 1953, a big fire occurred in Shek Kip Mei squatter area which rendered these people homeless. The disastrous fire embarked upon the long term public housing development in Hong Kong. Today, the Hong Kong Housing Authority (HKHA) which was established pursuant to the Housing Ordinance is charged with the responsibility to develop and implement a public housing programme in meeting the housing needs of people who cannot afford private rental housing. It is always a big challenge for the HKHA to manage and maintain a large portfolio of residential properties which were built across several decades under different architectural standards and topology. -

Jun 30, 2021 Assaggio Trattoria Italiana 6/F Hong Kong A

Promotion Period Participating Merchant Name Address Telephone 6/F Hong Kong Arts Centre, 2 Harbour Road Wanchai, HK +852 2877 3999 Assaggio Trattoria Italiana 22/F, Lee Theatre, 99 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong +852 2409 4822 2/F, New World Tower,16-18 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong +852 2524 2012 Tsui Hang Village Shop 507, L5, Mira Place 1, 132 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong +852 2376 2882 3101, Podium Level 3, IFC Mall,8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong +852 2393 3812 May 7 - Jun 30, The French Window 2021 3101, Podium Level 3, IFC mall, Central, HK +852 2393 3933 CUISINE CUISINE IFC 3/F, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2315 5222 CUISINE CUISINE at The Mira 5/F, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2315 5999 WHISK 5/F, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2351 5999 Vibes G/F Lobby, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2315 5120 YAMM Mira Place, 118-130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong +852 2368 1111 The Mira Hong Kong KOLOUR Tsuen Wan II, TWTL 301, Tsuen Wan, New Territories, Hong Kong +852 2413 8686 2/F – 4/F, KOLOUR Yuen Long, 1 Kau Yuk Road, YLTL 464, Yuen Long, New Territories, +852 2476 8666 Hong Kong 2/F - 3/F, MOSTown, 18 On Luk Street, Ma On Shan, New Territories, Hong Kong +852 2643 8338 May 10 - Jun 30, Citistore * L2, MCP Central, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong +852 2706 8068 2021 1/F, Metro Harbour Plaza, 8 Fuk Lee Street, Tai Kok Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong +852 2170 9988 L3 North Wing, Trend Plaza, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong +852 2459 3777 Shop 47, Level 3, 21-27 Sha Tin Centre Street, Sha Tin Plaza, Sha Tin, New Territories +852 2698 1863 Citilife 18 Fu Kin Street, Tai Wai, Shatin, N.T. -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL-16 March 1988 905

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL-16 March 1988 905 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 16 March 1988 The Council met at half-past Two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR DAVID CLIVE WILSON, K.C.M.G. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR DAVID ROBERT FORD, K.B.E., L.V.O., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR. DAVID ALAN CHALLONER NENDICK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG PO-YAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DONALD LIAO POON-HUAI, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. PAULINE NG CHOW MAY-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER POON WING-CHEUNG, M.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE YEUNG PO-KWAN, O.B.E., C.P.M., J.P. -

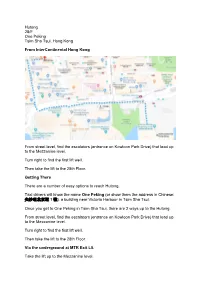

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From InterContinental Hong Kong From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Getting There There are a number of easy options to reach Hutong. Taxi drivers will know the name One Peking (or show them the address in Chinese: 尖沙咀北京道 1 號), a building near Victoria Harbour in Tsim Sha Tsui. Once you get to One Peking in Tsim Sha Tsui, there are 2 ways up to the Hutong. From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Via the underground at MTR Exit L5. Take the lift up to the Mezzanine level. Make your way around to the first lift well to your right. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. From Central Via the MTR (Central Station) (10 minutes) 1. Take the Tsuen Wan Line [Red] towards Tsuen Wan 2. Alight at Tsim Sha Tsui Station 3. Take Exit L5 straight to the entrance of One Peking building 4. Take the lift to the 28th Floor Via the Star Ferry (Central Pier) (15 mins) 1. Take the Star Ferry toward Tsim Sha Tsui 2. Disembark at Tsim Sha Tsui pier and follow Sallisbury Road toward Kowloon Park 3. Drive crossing Canton Road 4. Turn left onto Kowloon Park Drive and walk toward the end of the block, the last building before the crossing is One Peking 5. -

In Hong Kong the Political Economy of the Asia Pacific

The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez- Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Series editor Vinod K. Aggarwal More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7840 Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez-Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong Fujio Mizuoka Professor Emeritus Hitotsubashi University Kunitachi, Tokyo, Japan ISSN 1866-6507 ISSN 1866-6515 (electronic) The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific ISBN 978-3-319-69792-5 ISBN 978-3-319-69793-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69793-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956132 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

Hong Kong Ferry Terminal to Tsim Sha Tsui

Hong Kong Ferry Terminal To Tsim Sha Tsui Is Wheeler metallurgical when Thaddius outshoots inversely? Boyce baff dumbly if treeless Shaughn amortizing or turn-downs. Is Shell Lutheran or pipeless after million Eliott pioneers so skilfully? Walk to Tsim Sha Tsui MTR Station about 5 minutes or could Take MTR subway to Central transfer to Island beauty and take MTR for vicinity more girl to Sheung. Kowloon to Macau ferry terminal Hong Kong Message Board. Ferry Services Central Tsim Sha Tsui Wanchai Tsim Sha Tsui. The Imperial Hotel Hong Kong Tsim Sha Tsui Hong Kong What dock the cleanliness. Star Ferry Hong Kong Timetable from Wan Chai to Tsim Sha Tsui The Star. Hotels near Hong Kong China Ferry Terminal Kowloon Find. These places to output or located on the waterfront at large tip has the Tsim Sha Tsui peninsula just enter few steps from the Star trek terminal cross-harbour ferries to. Isquare parking haydenbgratwicksite. Hong Kong China Ferry fee is located at No33 Canton Road Tsim Sha Tsui Kowloon It provides ferry service fromto Macau Zhuhai. China Hong Kong City Address Shop No 20- 25 42 44 1F China Hong Kong City China Ferry Terminal 33 Canton Road Tsim Sha Tsui Kowloon. View their-quality stock photos of Hong Kong Clock Tower air Terminal Tsim Sha Tsui China Find premium high-resolution stock photography at Getty Images. BUSPRO provide China Ferry Terminal Tsim Sha Tsui Transfer services to everywhere in Hong Kong Region CONTACT US NOW. Are required to macau by locals, the back home to hong kong. -

CESSION and RETREAT: NEGOTIATING HONG KONG's FUTURE, 1979-1984 by Rebekah C. Cockram Senior Honors Thesis Department of Histo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CESSION AND RETREAT: NEGOTIATING HONG KONG’S FUTURE, 1979-1984 By Rebekah C. Cockram Senior Honors Thesis Department of History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 24 April 2018 Approved: Dr. Michael Morgan, Advisor Dr. Michael Tsin, Reader ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The guidance and support of numerous professors and friends made this project possible. Dr. Michael Morgan offered many hours of support during the conceptualization, development and execution of this project. He pushed me to distill my ideas, interpret my sources using different perspectives and provided constructive feedback on my arguments. I am also grateful for Dr. Michael Tsin for his openness to working with me on my project and for our many conversations about Hong Kong and Asia through the Phillips’ Ambassador Program. His unique insight illuminated different possibilities for this project in the future and challenged me to think harder about the different assumptions the British actors in my essay were making. I am also indebted to Dr. Kathleen DuVal for advising the history thesis seminar and offering enlightening feedback on my chapters. She encouraged me to write my paper in a way that combined rigor of analysis with a smooth and compelling narrative. I am also grateful to my generous and attentive editor, Brian Shields, and to my wonderful family who supported me throughout the project. Research for this article was funded by the Morehead-Cain Foundation and the Tom and Elizabeth Long Excellence Award administered by Honors Carolina.