GUINEA BISSAU WE Labé Labé Boké S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberia BULLETIN Bimonthly Published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia

LibeRIA BULLETIN Bimonthly published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia 1 October 2004 Vol. 1, Issue No. 4 Voluntary Repatriation Started October 1, 2004 The inaugural convoys of 77 Liberian refugees from Sierra Leone and 97 from Ghana arrived to Liberia on October 1, 2004, which marked the commencement of the UNHCR voluntary repatriation. Only two weeks prior to the beginning of the repatriation, the County Resettlement Assessment Committee (CRAC) pro- claimed four counties safe for return – Grand Cape Mount, Bomi, Gbarpolu and Margibi. The first group of refugees from Sierra Leone is returning to their homes in Grand Cape Mount. UNHCR is only facilitating re- turns to safe areas. Upon arrival, returnees have the option to spend a couple of nights in transit centers (TC) before returning to their areas of origin. At the TC, they received water, cooked meals, health care, as well as a two-months resettlement ration and a Non- Signing of Tripartite Agreement with Guinea Food Items (NFI) package. With the signing of the Tripartite Agreements, which took place in Accra, Ghana, on September 22, 2004 with the Ghanian government and in Monrovia, Liberia, on September 27, 2004 with the governments of Si- erra Leone, Guinea and Cote d’Ivorie, binding agree- ment has been established between UNHCR, asylum countries and Liberia. WFP and UNHCR held a regional meeting on Septem- ber 27, 2004 in Monrovia and discussed repatriation plans for Liberian refugees and IDPs. WFP explained that despite the current food pipeline constraints, the repatriation of refugees remains a priority for the Country Office. -

Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program

Survey ID _________________________ Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program Section I Survey Identifier Information Q 1. Household ID: Lofa Voinjama | Zorzor [circle one] PA#: COUNTY DISTRICT TOWN NAME HH # Q 2. Date/Time of Interview: A. (DD/MM/YY) |__|__|/|__|__|/|__|__| B. (24 hr clock) |__|__| : |__|__| Q 3. Enumerator Name and ID: Q 4. Enumerator ID First Name Last Name First Respondent Information Q 5. Name of First respondent (normally head of household) First Name Last Name Q 6. Is first respondent the Head of Household? Q 7. Relation with head of Househod: No Yes If not: (Code P) 0 1 Q 8. Was this person the head of his/her own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 Can you tell us the name of one friend or family member who will know where you are or how to contact you? Q 9. Name of contact person Q 10 First Name Last Name Relationship [Use Code P] Q 11. Contact Information County Code Q _____ _____ District Code Q ____ ____ ____ ____ Town Name ______________________________ Second Respondent Information (Enter once you begin 2nd interview) Q 12. Name of 2nd Respondent for (Section IV to end): Q 13 Roster Number: First Name Last Name Q 14. How was the second respondent selected? Randomly selected from all HH members Randomly selected from all available aged 18 and over HH members aged 18 and over 0 1 Q 15. Was this person the head of his own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 1 Survey ID _________________________ II Pre War and Post War Household Roster I want you to think about your household today. -

Sexual Gender-Based Violence and Health Facility Needs Assessment

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION SEXUAL GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE AND HEALTH FACILITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT (LOFA, NIMBA, GRAND GEDEH AND GRAND BASSA COUNTIES) LIBERIA By PROF. MARIE-CLAIRE O. OMANYONDO RN., Ph.D SGBV CONSULTANT DATE: SEPTEMBER 9 - 29, 2005 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AFELL Association of Female Lawyers of Liberia HRW Human Rights Watch IDP Internally Displaced People IRC International Rescue Committee LUWE Liberian United Women Empowerment MSF Medecins Sans Frontières NATPAH National Association on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Womn and Children NGO Non-Governmental Organization PEP Post-Exposure Prophylaxis PTSD Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder RHRC Reproductive Health Response in Conflict SGBV Sexual Gender-Based Violence STI Sexually Transmitted Infection UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund WFP World Food Programme WHO World Health Organization 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Problem Statement 1.1. Research Question 1.2. Objectives II. Review of Literature 2.1. Definition of Concepts 2.2. Types of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence 2.3. Consequences of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence 2.4. Sexual and Gender-Based Violence III. Methodology 3.1 Sample 3.2 3.3 Limitation IV. Results and Discussion A. Community Assessment results A.1. Socio-Demographic characteristics of the Respondents A.1.a. Age A.1.b. Education A.1.c. Religious Affiliation A.1.d. Ethnic Affiliation A.1.e. Parity A.1.f. Marital Status A.2. Variables related to the study 3 A.2.1. Types of Sexual Violence A.2.2. Informing somebody about the incident Reaction of people you told A.2.3. Consequences of Sexual and Gender Based Violence experienced by the respondents A.2.3.1. -

Rebel Ladies

CHAPTER XIII Rebel Ladies I will not attempt to describe [my] first interview with my family since the commencement of my exile in August.1 I was now with them at the house of my son-in-law Dr. B. B. Lenoir. But how altered that house, how changed his interesting family. Lenoir's is a principal and important sta tion and depot on the E. T. & G. R. R. twenty miles below Knoxville. In some respects it is the most valuable property in Tennessee or the West. It contains between two and three thousand acres of land, much of it island and river bottom. Upon it have been erected a cotton spinning fac tory, planing machines, mills and other large improvements of several kinds. When I last saw it before there were in its barns, cribs, meat houses, any extent of these supplies necessary for the subsistence of an army. The cellars were filled with groceries of all kinds. The forests on the property were scarcely excelled anywhere for their extent or their value. These extended to and embraced the dwelling house and the out buildings. The outstanding crop in August before promised a yield of _ About September I, the enemy came and took whatever of supplies they chose to of all kinds. They exhausted the smokehouse and cellar of all the necessaries of life, cut down the forests as they pleased, and erected in their fertile fields villas of cabins for their soldiers. They took possession of Dr. Lenoir's office and established in it their headquarters for General James M. -

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (As of 17 Fev 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (as of 17 Fev 2015) Banian SENEGAL Albadariah Mamouroudou MALI Djimissala Kobala Centre GUINEA-BISSAU Mognoumadou Morifindou GUINEA Karala Sangardo Linko Sessè Baladou Hérémakono Tininkoro Sirana De Beyla Manfran Silakoro Samala Soromaya Gbodou Sokowoulendou Kabadou Kankoro Tanantou Kerouane Koffra Bokodou Togobala Centre Gbangbadou Koroukorono Korobikoro Koro Benbèya Centre Gbenkoro SIERRA LEONE Kobikoro Firawa Sassèdou Korokoro Frawanidou Sokourala Vassiadou Waro Samarami Worocia Bakokoro Boukorodou Kamala Fassousso Kissidougou Banankoro Bablaro Bagnala Sananko Sorola Famorodou Fermessadou Pompo Damaro Koumandou Samana Deila Diassodou Mangbala Nerewa LIBERIA Beindou Kalidou Fassianso Vaboudou Binemoridou Faïdou Yaradou Bonin Melikonbo Banama Thièwa DjénédouKivia Feredou Yombiro M'Balia Gonkoroma Kemosso Tombadou Bardou Gberékan Sabouya Tèrèdou Bokoni Bolnin Boninfé Soumanso Beindou Bondodou Sasadou Mama Koussankoro Filadou Gnagbèdou Douala Sincy Faréma Sogboro Kobiramadou Nyadou Tinah Sibiribaro Ouyé Allamadou Fouala Regional Capital Bolodou Béindou Touradala Koïko Daway Fodou 1 Dandou Baïdou 1 Kayla Kama Sagnola Dabadou Blassana Kamian Laye Kondiadou Tignèko Kovila Komende Kassadou Solomana Bengoua Poveni Malla Angola Sokodou Niansoumandou Diani District Capital Kokouma Nongoa Koïko Frandou Sinko Ferela Bolodou Famoîla Mandou Moya Koya Nafadji Domba Koberno Mano Kama Baïzéa Vassala Madina Sèmèkoura Bagbé Yendemillimo Kambadou Mohomè Foomè Sondou Diaboîdou Malondou Dabadou Otol Beindou Koindou -

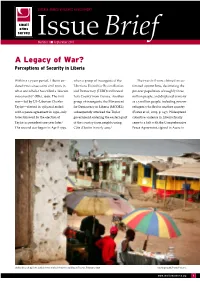

A Legacy of War? Perceptions of Security in Liberia

Liberia ARMeD ViOLeNCe aSSeSSMeNT Issue Brief Number 1 September 2011 A Legacy of War? Perceptions of Security in Liberia Within a 14-year period, Liberia en- when a group of insurgents of the The two civil wars claimed an es- dured two consecutive civil wars in Liberians United for Reconciliation timated 250,000 lives, decimating the what one scholar has called a ‘descent and Democracy (LURD) infiltrated pre-war population of roughly three into anarchy’ (Ellis, 1999). The first Lofa County from Guinea. Another million people, and displaced as many war—led by US–Liberian Charles group of insurgents, the Movement as 1.5 million people, including 700,000 Taylor—started in 1989 and ended for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), refugees who fled to another country with a peace agreement in 1996, only subsequently attacked the Taylor (Foster et al., 2009, p. 247). Widespread to be followed by the election of government, entering the eastern part collective violence in Liberia finally Taylor as president one year later.1 of the country from neighbouring came to a halt with the Comprehensive The second war began in April 1999, Côte d’Ivoire in early 2003.2 Peace Agreement, signed in Accra in Stallholders set up their stalls in front of a bullet-marked building in Fissebu, February 2008. © George Osodi/Panos Pictures www.smallarmssurvey.org 1 August 2003. With President Taylor in conditions in mid-2010 improved concludes by summarizing key policy- exile, the National Transitional Govern- over the previous year. relevant findings. ment of Liberia was established to ease Around 70 per cent of respondents the shift from war to peace. -

Appeal E-Mail: [email protected]

150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 Appeal e-mail: [email protected] Coordinating Office Liberia Assistance to IDPs and Returnees - AFLR11 Appeal Target: US$ 297,628 Geneva, March 30, 2001 Dear Colleagues, The fighting in Liberia’s Kolahun District in Lofa between the Liberian Government troops and the rebels have caused great suffering to tens of thousands of people and responsible for the destruction of infrastructures including private homes, public buildings, schools, hospitals and clinics. The belligerents in the war have destroyed and looted homes and responsible for a number of people who have been killed. In addition to the 20,000 people who were displaced in the October, 2000 fighting another over 5,000 people have been displaced in the latest fighting this February, and have taken refugee in the districts of Kongba, Gbarma and Tubmanburg city in Bomi county. Lutheran World Federation / World Service (LWF/WS) proposes to assist IDPs in Lofa and Bomi Counties, affected by the current hostilities especially in the district of Salayea. Special attention will be given to the internally displaced numbering 25,000. The assistance will include: · Food distribution · Non Food Items (mainly blankets, and clothes) · Health (Support to Clinics) · Water & Sanitation · Seeds and Tools ACT is a worldwide network of churches and related agencies meeting human need through coordinated emergency response. The ACT Coordinating Office is based with the World Council of Churches (WCC) -

IOM Guinea Ebola Response Situation Report, 8-31 March 2016

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Guinea Ebola Response International Organization for Migration

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

General AP Hill at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Park Seminar General A.P. Hill at Gettysburg: A Study of Character and Command Matt Atkinson If not A. P. Hill, then who? May 2, 1863, Orange Plank Road, Chancellorsville, Virginia – In the darkness of the Wilderness, victory or defeat hung in the balance. The redoubtable man himself, Stonewall Jackson, had ridden out in front of his most advanced infantry line to reconnoiter the Federal position and was now returning with his staff. Nervous North Carolinians started to fire at the noises of the approaching horses. Voices cry out from the darkness, “Cease firing, you are firing into your own men!” “Who gave that order?” a muffled voice in the distance is heard to say. “It’s a lie! Pour it into them, boys!” Like chain lightning, a sudden volley of musketry flashes through the woods and the aftermath reveals Jackson struck by three bullets.1 Caught in the tempest also is one of Jackson’s division commanders, A. P. Hill. The two men had feuded for months but all that was forgotten as Hill rode to see about his commander’s welfare. “I have been trying to make the men cease firing,” said Hill as he dismounted. “Is the wound painful?” “Very painful, my arm is broken,” replied Jackson. Hill delicately removed Jackson’s gauntlets and then unhooked his sabre and sword belt. Hill then sat down on the ground and cradled Jackson’s head in his lap as he and an aide cut through the commander’s clothing to examine the wounds. -

Analyzing Liberia's Rebels Using Satellite Data

Predators or Protectors? Analyzing Liberia's Rebels Using Satellite Data Nicholai Lidow∗ Stanford University February 19, 2011 Abstract This paper uses satellite imagery to measure local food production during Liberia's civil war, 1989-2003. Contrary to media reports of rampant abuse and the predictions of existing theories, I show that the NPFL rebels provided enough security for civilians to maintain farming at pre-war levels, while other rebels triggered significant declines in food production due to their predation. I propose a new theory of rebel group behavior that focuses on the motives of external patrons who provide resources to rebel leaders. When patrons benefit from disciplined groups, they provide financing to qualified leaders, who then use these resources to encourage cooperation among their troops. Other patrons, seeking to manipulate the group, support low quality leaders and withhold resources that could strengthen leader control. The theory predicts food production to follow a spatial pattern based on distance to rebel bases and lootable resources and finds support in the data. 1 Introduction In this paper I use satellite imagery to measure the effects of rebel group behavior on local food production during Liberia's civil war, 1989-2003, as one aspect of civilian abuse. When ∗I wish to acknowledge Jim Fearon, Karen Jusko, David Laitin, Jonathan Rodden, Jonathan Wand, and members of the Working Group in African Political Economy. Support from the National Science Foundation (SES-1023712) allowed for the purchase of satellite imagery. All mistakes are my own. 1 rebel groups are highly predatory, civilians struggle to gain access to food and other essen- tials, resulting in high levels of displacement, malnutrition, and disease. -

LIBERIA War in Lofa County Does Not Justify Killing, Torture and Abduction

LIBERIA War in Lofa County does not justify killing, torture and abduction “One of the ATU [Anti-Terrorist Unit] told the others ‘He is going to give us information on the rebel business’. They took me to Gbatala. I saw many holes in which prisoners were held. I could hear them crying, calling for help and lamenting that they were hungry and they were dying.” Testimony of a young man detained at Gbatala military base in August 2000. Introduction The continuation of hostilities in Liberia cannot be used as a justification for killing, torture and abduction. Unarmed civilians are again the main victims of fighting in Liberia – a country still bearing the scars of its seven-year civil war when massive human rights abuses were committed by all sides with impunity. Since mid-2000, dozens of civilians have allegedly been extrajudicially executed and more than 100 civilians, including women, have been tortured by the Anti-Terrorist Unit (ATU) and other Liberian security forces. People have been tortured while held incommunicado, especially at the military base in Gbatala, central Liberia, and the ATU cells behind the Executive Mansion, the office of the presidency in Monrovia, the capital. Women and young girls have been raped by the security forces. All these victims were suspected of backing the armed incursions by Liberian armed opposition groups from Guinea into Lofa County, the northern region of Liberia bordering with Guinea and Sierra Leone. The security forces have mostly targeted members of the Mandingo ethnic group whom they associate with ULIMO-K 1 , a predominantly Mandingo warring faction in the 1989-1996 Liberian civil war, accused by the Liberian government of being responsible for the armed incursions into Lofa County in 1999, notably in April and August of that year and since July 2000.