Erdogan's New Sultanate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making the Afro-Turk Identity

Vocabularies of (In)Visibilities: (Re)Making the Afro-Turk Identity AYşEGÜL KAYAGIL* Abstract After the abolition of slavery towards the end of the Ottoman Empire, the majority of freed black slaves who remained in Anatolia were taken to state “guesthouses” in a number of cities throughout the Empire, the most im- portant of which was in Izmir. Despite their longstanding presence, the descendants of these black slaves – today, citizens of the Republic of Turkey – have until recently remained invisible both in the official historiography and in academic scholarship of history and social science. It is only since the establishment of the Association of Afro-Turks in 2006 that the black popu- lation has gained public and media attention and a public discussion has fi- nally begun on the legacies of slavery in Turkey. Drawing on in-depth inter- views with members of the Afro-Turk community (2014-2016), I examine the key role of the foundation of the Afro-Turk Association in reshaping the ways in which they think of themselves, their shared identity and history. Keywords: Afro-Turks, Ottoman slavery, Turkishness, blackness Introduction “Who are the Afro-Turks?” has been the most common response I got from my friends and family back home in Turkey, who were puzzled to hear that my doctoral research concerned the experiences of the Afro-Turk commu- nity. I would explain to them that the Afro-Turks are the descendants of en- slaved Africans who were brought to the Ottoman Empire over a period of 400 years and this brief introduction helped them recall. -

Reconciling Statism with Freedom: Turkey's Kurdish Opening

Reconciling Statism with Freedom Turkey’s Kurdish Opening Halil M. Karaveli SILK ROAD PAPER October 2010 Reconciling Statism with Freedom Turkey’s Kurdish Opening Halil M. Karaveli © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 1619 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodav. 2, Stockholm-Nacka 13130, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Reconciling Statism with Freedom: Turkey’s Kurdish Opening” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and ad- dresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University and the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse commu- nity of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lec- tures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public dis- cussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of the authors only, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Joint Center or its sponsors. -

The Green Movement in Turkey

#4.13 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey FEATURE ARTICLES THE GREEN MOVEMENT IN TURKEY DEMOCRACY INTERNATIONAL POLITICS HUMAN LANDSCAPE AKP versus women Turkish-American relations and the Taner Öngür: Gülfer Akkaya Middle East in Obama’s second term The long and winding road Page 52 0Nar $OST .IyeGO 3erkaN 3eyMeN Page 60 Page 66 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Content Editor’s note 3 Q Feature articles: The Green Movement in Turkey Sustainability of the Green Movement in Turkey, Bülent Duru 4 Environmentalists in Turkey - Who are they?, BArë GenCer BAykAn 8 The involvement of the green movement in the political space, Hande Paker 12 Ecofeminism: Practical and theoretical possibilities, %Cehan Balta 16 Milestones in the Õght for the environment, Ahmet Oktay Demiran 20 Do EIA reports really assess environmental impact?, GonCa 9lmaZ 25 Hydroelectric power plants: A great disaster, a great malice, 3emahat 3evim ZGür GürBüZ 28 Latest notes on history from Bergama, Zer Akdemir 34 A radioactive landÕll in the heart of ÊXmir, 3erkan OCak 38 Q Culture Turkish television series: an overview, &eyZa Aknerdem 41 Q Ecology Seasonal farm workers: Pitiful victims or Kurdish laborers? (II), DeniZ DuruiZ 44 Q Democracy Peace process and gender equality, Ulrike Dufner 50 AKP versus women, Gülfer Akkaya 52 New metropolitan municipalities, &ikret TokSÇZ 56 Q International politics Turkish-American relations and the Middle East in Obama’s second term, Pnar DoSt .iyeGo 60 Q Human landscape Taner Öngür: The long and winding road, Serkan Seymen -

Lilo Linke a 'Spirit of Insubordination' Autobiography As Emancipatory

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ autobiography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/177/ Version: Full Version Citation: Ogurla, Anita Judith (2016) Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ auto- biography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Lilo Linke: A ‘Spirit of Insubordination’ Autobiography as Emancipatory Pedagogy; A Turkish Case Study Anita Judith Ogurlu Humanities & Cultural Studies Birkbeck College, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, February 2016 I hereby declare that the thesis is my own work. Anita Judith Ogurlu 16 February 2016 2 Abstract This thesis examines the life and work of a little-known interwar period German writer Lilo Linke. Documenting individual and social evolution across three continents, her self-reflexive and autobiographical narratives are like conversations with readers in the hope of facilitating progressive change. With little tertiary education, as a self-fashioned practitioner prior to the emergence of cultural studies, Linke’s everyday experiences constitute ‘experiential learning’ (John Dewey). Rejecting her Nazi-leaning family, through ‘fortunate encounter[s]’ (Goethe) she became critical of Weimar and cultivated hope by imagining and working to become a better person, what Ernst Bloch called Vor-Schein. Linke’s ‘instinct of workmanship’, ‘parental bent’ and ‘idle curiosity’ was grounded in her inherent ‘spirit of insubordination’, terms borrowed from Thorstein Veblen. -

Whiteness As an Act of Belonging: White Turks Phenomenon in the Post 9/11 World

WHITENESS AS AN ACT OF BELONGING: WHITE TURKS PHENOMENON IN THE POST 9/11 WORLD ILGIN YORUKOGLU Department of Social Sciences, Human Services and Criminal Justice The City University of New York [email protected] Abstract: Turks, along with other people of the Middle East, retain a claim to being “Cau- casian”. Technically white, Turks do not fit neatly into Western racial categories especially after 9/11, and with the increasing normalization of racist discourses in Western politics, their assumed religious and geographical identities categorise “secular” Turks along with their Muslim “others” and, crucially, suggest a “non-white” status. In this context, for Turks who explicitly refuse to be presented along with “Islamists”, “whiteness” becomes an act of belonging to “the West” (instead of the East, to “the civilised world” instead of the world of terrorism). The White Turks phenomenon does not only reveal the fluidity of racial categories, it also helps question the meaning of resistance and racial identification “from below”. In dealing with their insecurities with their place in the world, White Turks fall short of leading towards a radical democratic politics. Keywords: Whiteness, White Turks, Race, Turkish Culture, Post 9/11. INTRODUCTION: WHY STUDY WHITE TURKISHNESS Until recently, sociologists and social scientists have had very little to say about Whiteness as a distinct socio-cultural racial identity, typically problematizing only non-white status. The more recent studies of whiteness in the literature on race and ethnicity have moved us beyond a focus on racialised bodies to a broader understanding of the active role played by claims to whiteness in sustaining racism. -

Brazil-Turkey Fundação Alexandre De Gusmão Fundação Two Emerging Powers Intensify Emerging Powers Two

coleção Internacionais Relações Relações coleção coleção Internacionais 811 Ekrem Eddy Güzeldere is a political Eddy Güzeldere Ekrem Ekrem Eddy Güzeldere The bilateral relations of Brazil and Turkey scientist from Munich with a specialization Within the theoretic frame of role theory, this book represents a first attempt at are a little researched subject. Therefore, this in international relations. He holds a PhD describing the bilateral relations of Brazil and Turkey since the 1850s until 2017 book offers a first attempt at analyzing both (2017) from the University of Hamburg. with an emphasis on contemporary relations. Both states are treated as emerging the political, economic, cultural and academic From 2005 to October 2015 he worked in powers, which intensify their relations, because of two main motivations: to raise bilateral relations, especially since they have Istanbul for the German political foundation their status in international affairs and for economic reasons. In the period of 2003 been intensifying in the 2000s. However, there Heinrich Böll, an international ESI think until 2011, Brazil and Turkey succeeded in intensifying their relations in many is also a historic chapter about the relations in tank, as a journalist and political analyst fields, with 2010 being the year of most intensive politico-diplomatic relations, the 19th century, which in its depth, using both for international media and consultancies. because of both a major diplomatic initiative, the Tehran Declaration, and an Turkish and Portuguese-language sources, Before moving to Istanbul, he worked in ambitious Strategic Partnership. The economic relations reached a high in 2011 represents a first endeavor in English. -

I TURKEY and the RESCUE of JEWS DURING the NAZI ERA: a RE-APPRAISAL of TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS in TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS in OCCUPIED FRANCE

TURKEY AND THE RESCUE OF JEWS DURING THE NAZI ERA: A REAPPRAISAL OF TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS IN TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS IN OCCUPIED FRANCE by I. Izzet Bahar B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, 1974 M.Sc. in Electrical Engineering, Bosphorus University, Istanbul, 1977 M.A. in Religious Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Art and Sciences in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cooperative Program in Religion University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by I. Izzet Bahar It was defended on March 26, 2012 And approved by Clark Chilson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Religious Studies Seymour Drescher, PhD, University Professor, History Pınar Emiralioglu, PhD, Assistant Professor, History Alexander Orbach, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Adam Shear, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Dissertation Advisor: Adam Shear, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies ii Copyright © by I. Izzet Bahar 2012 iii TURKEY AND THE RESCUE OF JEWS DURING THE NAZI ERA: A RE-APPRAISAL OF TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS IN TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS IN OCCUPIED FRANCE I. Izzet Bahar, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This study aims to investigate in depth two incidents that have been widely presented in literature as examples of the humanitarian and compassionate Turkish Republic lending her helping hand to Jewish people who had fallen into difficult, even life threatening, conditions under the racist policies of the Nazi German regime. The first incident involved recruiting more than one hundred Jewish scientists and skilled technical personnel from German-controlled Europe for the purpose of reforming outdated academia in Turkey. -

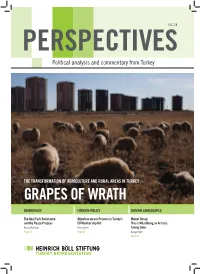

Grapes of Wrath

#6.13 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey THE TRANSFORMATION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AREAS IN TURKEY GRAPES OF WRATH DEMOCRACY FOREIGN POLICY HUMAN LANDSCAPES The Gezi Park Resistance Objective versus Process in Turkey’s Memet Aksoy: and the Peace Process EU Membership Bid This is What Being an Artist is: Nazan Üstündağ Erhan İçener Taking Sides Page 54 Page 62 Ayşegül Oğuz Page 66 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Contents From the editor 3 ■ Cover story: The transformation of agriculture and rural areas in Turkey The dynamics of agricultural and rural transformation in post-1980 Turkey Murat Öztürk 4 Europe’s rural policies a la carte: The right choice for Turkey? Gökhan Günaydın 11 The liberalization of Turkish agriculture and the dissolution of small peasantry Abdullah Aysu 14 Agriculture: Strategic documents and reality Ali Ekber Yıldırım 22 Land grabbing Sibel Çaşkurlu 26 A real life “Grapes of Wrath” Metin Özuğurlu 31 ■ Ecology Save the spirit of Belgrade Forest! Ünal Akkemik 35 Child poverty in Turkey: Access to education among children of seasonal workers Ayşe Gündüz Hoşgör 38 Urban contexts of the june days Şerafettin Can Atalay 42 ■ Democracy Is the Ergenekon case a step towards democracy? Orhan Gazi Ertekin 44 Participative democracy and active citizenship Ayhan Bilgen 48 Forcing the doors of perception open Melda Onur 51 The Gezi Park Resistance and the peace process Nazan Üstündağ 54 Marching like Zapatistas Sebahat Tuncel 58 ■ Foreign Policy Objective versus process: Dichotomy in Turkey’s EU membership bid Erhan İcener 62 ■ Culture Rural life in Turkish cinema: A location for innocence Ferit Karahan 64 ■ Human Landscapes from Turkey This is what being an artist is: Taking Sides Memet Aksoy 66 ■ News from HBSD 69 Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Turkey Represantation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

The European Transformation of Modern Turkey

THE EUROPEAN TRANSFORMATION OF MODERN TURKEY THE EUROPEAN TRANSFORMATION OF MODERN TURKEY BY KEMAL DERVIŞ MICHAEL EMERSON DANIEL GROS SINAN ÜLGEN CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES BRUSSELS ECONOMICS AND FOREIGN POLICY FORUM ISTANBUL This report presents the findings and recommendations of a joint project of the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and the Economics and Foreign Policy Forum (EFPF) of Istanbul, which aims to devise a strategy for the EU and Turkey in the pre-accession period. CEPS and EFPF gratefully acknowledge financial support for this project from the Open Society Institute of Istanbul, Akbank, Coca Cola, Dogus Holding, Finansbank and Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali (LUISS). The views expressed in this report are those of the authors writing in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect those of CEPS, EFPF or any other institution with which the contributors are associated. ISBN 92-9079-521-0 © Copyright 2004, Centre for European Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Centre for European Policy Studies. Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: 32 (0) 2 229.39.11 Fax: 32 (0) 2 219.41.51 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ceps.be Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. i Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1. The Evolving Nature of the EU and Turkey.......................................... 3 1.1 What Union would Turkey enter?.............................................................. 3 1.2 What Turkey would enter the Union?....................................................... -

The Racialization of Kurdish Identity in Turkey Murat Ergin Published Online: 01 Oct 2012

This article was downloaded by: [KU Leuven University Library] On: 11 February 2015, At: 11:22 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Ethnic and Racial Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 The racialization of Kurdish identity in Turkey Murat Ergin Published online: 01 Oct 2012. Click for updates To cite this article: Murat Ergin (2014) The racialization of Kurdish identity in Turkey, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37:2, 322-341, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2012.729672 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.729672 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Turkish Olympics: Festival Into the Gulen

The Turkish Olympics: Festival into the Gulen Movement By Sean David Hobbs Middle East Studies MA Thesis Prepared for: Dr. Helen Rizzo, Thesis Advisor Dr. Sherene Seikaly, First Reader Dr. Amy Austin Holmes, Second Reader Acknowledgements I recognize God, the Essence which moved me and made it possible to complete this thesis. Also I recognize my mother, I owe everything to her. My father was constantly there for me and his guiding words helped calm me as I went through the production of this thesis and the completion of my master’s degree. My uncles Bryan Hobbs and Joe Orler – and the rest of my family – were also helpful in giving me much needed support. Deepest gratitude to Gloria Powers, my NOLA matriarch, who taught me how “to hear that long snake moan.” Finally, Ralph, Father Joe and Sharron were life guides who lit the way and helped focus me toward this track. My advisor Dr. Helen Rizzo deserves a special thanks in that she gave this work focus and form and her kindness and encouragement were fundamental in completion of the thesis. My first reader, Dr. Sherene Seikaly, inspired me to create and criticize my initial fieldwork and she pushed me to grow as a student in her classes and in the writing of this thesis. Dr. Amy Austin Holms, my second reader, thankfully came in at the last moment as a reader when my original second reader had to leave the project. Dr. Holms’ ideas on the crafting and organization of the two ethnographies in this thesis clarified the final message. -

The Ups and Downs of Turkish Growth, 2002-2015: Political Dynamics, the European Union and the Institutional Slide*

The Ups and Downs of Turkish Growth, 2002-2015: Political Dynamics, the European Union and the Institutional Slide* Daron Acemoglu (MIT) Murat Ucer (Koc University and Global Source) Abstract We document a change in the character and quality of Turkish economic growth with a turning point around 2007 and link this change to the reversal in the nature of economic institutions, which eat underwent a series of growth-enhancing reforms following Turkey's financial crisis in 2001, but then started moving in the opposite direction in the second half of 2000s. This institutional reversal, we argue, is itself a consequence of a turnaround in political factors. The first phase coincided with a deepening in Turkish democracy under the prodding and the guidance of the European Union, and witnessed the waning of the military's influence and the broadening of effective political participation. As Turkey- European Union relations collapsed and internal political dynamics removed the checks against the domination of the governing party, in power since 2002, these political dynamics went into reverse and paved the way for the institutional slide that is largely responsible for the lower-paced and lower-quality growth Turkey has been experiencing since about 2007. Keywords: economic growth, emerging markets, institutions, institutional reversal, low-quality growth, Turkey. JEL Classification: E65, O52. * We thank Izak, Atiyas, Ilker Domac, Soli Ozel, Martin Raiser, Dani Rodrik and Sinan Ulgen for very useful comments on an earlier draft. The usual caveat applies. Though EU-Turkey relations are multifaceted, in this essay we focus on one specific aspect: the role of the EU in the improved institutional structure of Turkey during the early 2000s and the rapid growth that this engendered, and its subsequent more ominous contribution to the unraveling of these political and economic improvements.